Last month, on the heels of the men’s and women’s AW23 shows, fashion week observers and reporters exhaled in unison: finally, clothes. The sartorial pendulum had swung. In replace of “internet fashion” — memeable styles tailored for virality — were functional garments crafted for, well, getting dressed. One could say that the aforementioned shift is a predictable product of the industry’s cyclical nature. However, the arrival of normcore-nouveau is anything but arbitrary. According to fashion lore, it’s a sign of the times.

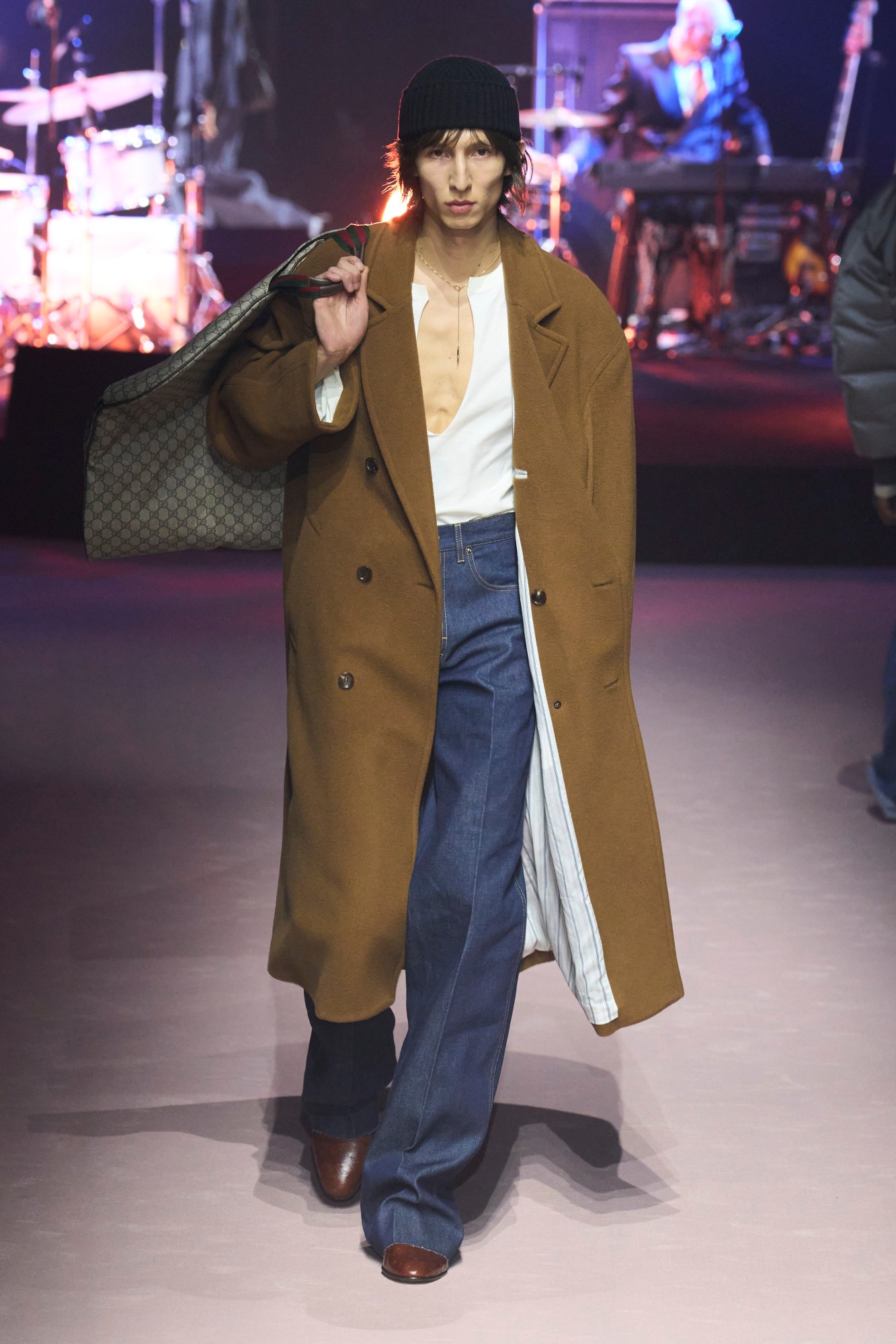

A style reminiscent of Phoebe Philo’s 2010s Céline, the return of luxurious minimalism was evident in every leg of the past fashion month. In New York, Proenza Schouler showed a series of black, navy, ivory and camel blazers. In London, Central Saint Martins’ Max Anthony, Toga, and even Nensi Dojaka showed khakis, jeans, and sweaters as centrepieces in their collections. In Milan, Gucci presented button-down shirts and belted slacks and Bottega Veneta closed their show with what was seemingly the most wearable look of all: tapered denim and a white tank accompanied by a light pink jacket tied around the waist, all crafted from trompe l’oeil leather (even pieces that bespeak painstaking craftsmanship are masquerading as ‘jeans and a tee.’) And finally, in Paris, Miu Miu and Loewe both fielded offerings that were notably normie compared to previous seasons. A renewed appreciation for elevated wardrobe necessities left consumers with a shared sentiment: all hail wearable clothing.

Once designers set the tone for the season ahead, retailers and customers followed suit (no pun intended). Noelle Sciacca, Senior Fashion Lead at The Real Real, says shoppers began gravitating toward socially normative dressing almost immediately. “Transitional, easy-to-wear pieces like wide-leg pants, blazers, pencils and midi skirts, cardigans, leather jackets and designer jeans have all been trending,” she says. Noelle highlights “stealth wealth,” a subcategory of understated luxury clothing well-defined by brands like Jil Sander, Phoebe Philo-era Céline, and Brunello Cucinelli, as a specific trend taking flight.

“This aesthetic has always been popular with our customers,” she adds. “However, right now we are seeing some serious demand for those brands.” Most notably, compared to last year on The Real Real, the search for Loro Piana trench coats is up 321 per cent, Loewe loafers is up 187 per cent, and Khaite tote bags is up 211 per cent. Mia Jacobs, the Youth Strategist for trend forecasting company WGSN, echoes Noelle’s findings. “We are seeing a shift away from performative tropes into something much more grounded,” she says. “When we look at data across retailers in both the UK & US, we see that cargo pants, chinos, and wide-leg trousers have all increased their percentage share of new-in styles.”

So, what is it about the current climate that ushered in the urge to return to basics? Social media, for a start. “This click-bait economy has made fashion very flat and more about shock value and thumb-stopping than wearability,” says Lily Miesmer, co-founder and designer behind the essentials-focused ready-to-wear brand Interior. Over the last decade, Instagram feeds have become oversaturated, meaning runway and street style content is tailored for a new kind of likeability — one that requires being really loud. The result? A circus-like feed, one riddled with cartoon-like Mschf boots, Lirika Matoshi’s strawberry dress, and the least wearable of all, digital fashion. And because there’s nothing worse than staying too long at the circus, we’ve arrived at loud-fashion fatigue. “On the surface, stunt dressing seems like it’s serving personality and individual expression,” Lily says. “But I would argue that it has reduced personal creativity to an algorithm.”

Another major player in the shift toward simpler styles is an impending recession. Emma McClendon, professor of fashion studies at St John’s University, says we can look as far back as The Great Depression for evidence of hyper-wearable clothing’s relevance during a financial downturn. “There’s this moment in the 1930s and 40s when America solidifies its place in the fashion landscape based on super functional clothing. People were looking for more economical and easy-to-care-for materials,” she says. “Items that were translatable or had more than one purpose.”

Fast forward to the wake of the 2008 financial crash, and again there was a collective gravitational pull toward modernised interpretations of functional clothing: quiet luxury à la The Row and Phoebe Philo. “There was a lot happening in fashion during that time,” Professor McClendon recalls. “On the one hand you had Gossip Girl and the arrival of Lady Gaga, and on the other you had this era of minimalism — drapey clothing with no branding,” she continues, drawing a parallel between now and then, a build up of too much happening concurrently (the exhaustive rise of the countless cores), and then a return to something simpler. “In the midst of chaos and confusion, this return to functionality is like a reset,” she says.

Whether referred to as normcore or stealth wealth, highly-wearable clothing has also repeatedly reentered the zeitgeist during moments of sociopolitical tension. Alla Eizenberg, a fashion historian and design professor at Parsons, goes as far as to say that this genre of clothing is a symbol of resistance. “This type of clothing has a rebellious DNA,” she explains. “If we really look back, the 1960s youth revolution was the first stake in the ground in regards to these clothes proliferating broader culture.” Professor Eizenberg is referring to casualwear, such as jeans, t-shirts, and other functional garments, which offered fertile ground for rebellion in fashion over the next several decades. In the 80s and 90s, radically subverted notions of luxury were present in Yohji Yamamoto’s and Comme des Garçons’ slashed and deconstructed suiting. In the 2000s, Vivienne Westwood reimagined denim with exaggerated hardware and distressed effects and released her collection of Anarchy Shirts. In the 2010s, Demna’s Vetements debut showed vintage jeans, oversized biker jackets and chintzy aprons rendered in patent leather. While each of these examples was created in response to a distinct sociopolitical climate, a distinct throughline joins them together: they are all, fundamentally, reinterpretations of everyday wear.

Our current embracing of “normal” clothing makes sense, then, considering today’s cultural backdrop. Recent crackdowns on women’s reproductive rights (June’s overturn of Roe v. Wade) and trans rights (March’s proposed Tennessee drag ban and the swell in TERF discourse in the mainstream media) are signifiers of a wider social shift, and while fashion isn’t necessarily a direct response to those events, social and clothing trends have historically coincided. Is that to say, then, that fashion’s drift toward more sober, normative territory is a reaction to political pressures of conservatism and normativity in society at large? Professor Eizenberg says yes, but not in the sense that we are dressing to mirror this rightward turn. Rather, the clothing represents unity under pressure. “The style is rooted in resistance to old bourgeois behavioural norms,” she argues. “These clothes are cultural depositories. So in moments of anxiety and oppression, we go back to these garments of solidarity.”

In the category of societal shifts, another piece of the puzzle to consider is the disruption of the gender binary. As fashion brands increasingly embrace a concertedly genderless approach, themes of universality and unity consequently translate to the clothes we see on runways and shop rails in a more literal way. “There is something happening around the topic of gender as it relates to wardrobe building that we haven’t seen in quite the same way before,” explains Professor McClendon, underscoring that expressing ourselves through clothing is intuitive, and that changes in the way we understand ourselves naturally result in changes in what wear. “When you add gender discourse to the cultural soup of economic downturn, social media, and political outbursts, you start to understand that these ongoing events can’t not have an impact on how you are getting dressed,” she concludes.

While it may be easier (and less time-consuming) to think of the clothing we choose to put on our bodies as simply that, discounting why those specific garments are showing up in our world at all would be missing out on the fun — the sentimentality, the humanness — of it all, especially when it comes to a wearable clothing revival. “My personal take is that a lot of fashion trends are very singular — they come and go. They do not always accumulate the meanings that the universal garments of this particular trend have,” Professor Eizenberg concludes. “Everyone has their favourite t-shirt. Everyone has a pair of jeans from junior high that they’ll always remember. And in a moment of uncertainty, we go back to this familiar place.” In other words, the return of wearable clothing is not a new phenomenon. It’s a sign of yet another great fashion reset, one that’s encoded in human nature.

Credits

Images via Spotlight