Anastasia Pavlova and her husband had every intention of staying in Kyiv when Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24, 2022, but after two days it became too scary. “We slept in the subway, I had panic attacks, and everyone around us was saying that Kyiv was going to be bombed,” she says. They moved to Ivano-Frankivsk, a city in western Ukraine, where they lived in a house of strangers. “We were comfortable, we supported each other, but we still really wanted to go home. We were out of work, constantly reading the news. It seemed that one day they would tell us that the war was over, but no, it continued.”

Maksym Snizhko, a photographer from Kyiv, left straight away too. He travelled 50 kilometres to his grandparents’ village with his family, negotiating a lack of public transport, surging taxi prices, traffic jams and a scramble for cash at the ATMs. “It resembled some post-apocalyptic movie,” he says. “But it was a frightening reality.” He spent the first week trying to grapple with the uncertainty about his future as Russian troops drew steadily closer. On the tenth day, he drove to western Ukraine with his friends, where he stayed until the liberation of Kyiv, Chernihiv and Sumy in April 2022.

“There is a feeling that you were turned 180 degrees and everything that you had spilled out from your pockets, you need time to collect it all now,” adds GORSAD, a trio of artists consisting of Julian, Masha and Vitya known for their vibrant staged photographs of Ukrainian youth. “Almost everything has changed,” they say in an email interview. In a new photo book and Instagram account: Stuck in Here, curated by the French photojournalist Orianne Ciantar Olive, Anastasia, Maksym and GORSAD are among the young Ukrainian photographers contributing to an archive of their homeland before and during the war.

“I have always been both astonished and revolted by the extent to which millions of people could see their lives changed overnight by a handful of madmen in power who would do anything to preserve or achieve their particular interests,” says Orianne, who has reported on the aftermath of war in the Balkans and the Middle East. “Without civilians, without being able to take them hostage, without using them as shields, wars would have no reason to exist. They are at the heart of conflicts and at the same time the last to be considered. The resulting injustice is unbearable. We take offence, we condemn, but nothing changes, that is the course of history,” she says. “So the best thing we can do is to tell it differently, to show it differently, to take a step aside.”

By giving Ukrainians the chance to craft the narrative around their war, Orianne hopes to avoid the sensationalism of the mainstream media that too often does the opposite to its intention and turns people away. “The public is so inundated with violent images that unfortunately it ends up not seeing them,” she says about wanting to do something to reach the public and draw their attention to the conflict. “I decided to take them by surprise, and show them images that come from the heart of the war but without any images of war.”

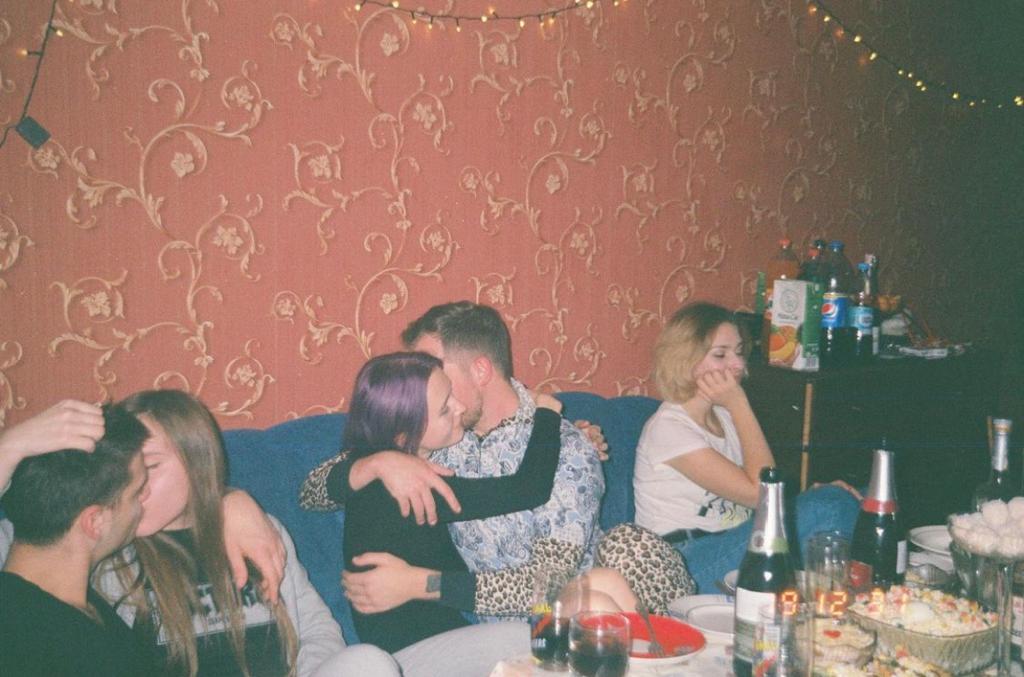

Instead, Stuck in Here chronicles Kyiv’s progressive youth culture, parties in Kharkiv, friends and lovers embracing. They are joyful moments but it’s nostalgic, a snapshot of a period long gone. “I try to immortalise the most vivid and beautiful moments of my life; these are parties, friends, architecture, nature, street shots that show how my city lives and just moments of life that I don’t want to forget,” Maksym says. Nineteen year old Aleksandra captures a night out in Kyiv a few days before the war began: two girls smiling under a giant neon cross, while a group of boys flick a finger for the camera. The images could be from a night in Berlin or London or New York, but they are images of men who had no idea they would soon be fighting for an independent Ukraine — fleeing with their families and leaving their life behind.

Another photographer called Anastasia, who is 22, shares a picture of couples kissing at a party in Kharkiv, empty wine bottles, food and mixers strewn across a long table. She was watching Euphoria on the day Russia invaded, waiting to hear back from a recruiter for an invitation to start work. “I realised that all my plans were ruined after I saw a glow at the city in the window at 5 am, as well as heard explosions and the sounds of planes flying over my house. Russia attacked Ukraine,” she writes in the book.

Roman, a 26-year-old photographer from Kyiv, photographed his friends in limbo as they fled the immediate danger of their hometown for western Ukraine. In muted tones and against a brown backdrop of striped wallpaper, he captures the monotony and instability of war but also friendship. “The name of this project is Stuck in here,” he writes, “and in a way, I am stuck. Stuck in a country with no certain future or stability, or a guarantee of physical safety. But I am stuck with the best people in this entire world.” He adds, “I wanted to highlight something that our entire country is hinging on – people. Military, medics, volunteers, diplomats, activists and so many more people that each do their part to overcome this horrendous evil. Without them, we’re nothing. Without them, I’m nothing.”

The project is a record of the country’s beauty. Pictures of nature, fields of flowers and cities that fuse Ukrainian Baroque, neo-Gothic and Modernist architecture. Roma Ilechko, a 25-year-old currently living in Lviv, says she hopes the images will preserve Ukrainian culture and the people’s “creativity, disobedience, indomitability, will. That is the way I can contribute and protect the history and culture of our motherland and present it to the public.”

“Life is beautiful, even in times of war,” says Anastasia Pavlova. “I fell even more in love with Kyiv, I began to pay more attention to the beauty of nature, to notice the details. We have to show our enemies that they can’t break us. Yes, I have changed, the world has changed, but I still want to notice the beautiful things around me. It gives me the strength not to give up.” She quotes Einstein: “‘There are only two ways to live this life. The first is as if miracles don’t exist, and the second is as if there are only miracles around.’ I choose the second way, and I want to see miracles and beauty in everything, even though this world is turning into hell.”

Stuck in Here seems to emphasise both the beauty and horrors simultaneously. It doesn’t reference the civilian death toll, which is believed to be more than 8,500 people, or the mass murders, tortures and rapes perpetuated by Russian aggressors in places like Bucha. But Orianne believes the public is already so inundated with images of the violence that they’ve become almost numb to them. She hopes to show that “ordinary life is the common ground of humanity, it is in these intimate spaces that we can quantify trauma, aggression, shock, survival mechanisms. They are often silent places, or at least they make less noise than a bomb or a rocket, and yet they contain all the inhumanity and chaos of war,” she says. Images of normality help people understand the conflict better, it’s what brings us together, she says, “it is what makes us say to ourselves ‘that could be me.’”

‘Stuck in Here: the book’ is now available for purchase online, here.

Credits

All photos courtesy of Stuck In Here.