My first interaction with the word “queer” was by way of a teacher in school calling me it in front of my class. It was a true sign of the times that no one, not even the other staff in the classroom, saw this to be an issue. But after hearing all my peers laugh in unison, it solidified my early understanding of “queer” as a slur and something I spent the rest of my school years trying to steer clear of being labelled. It was only when I got older and learned about the true origins of the word that I decided to identify as a queer man. I’m a gay Pakistani man who enjoys wearing nail varnish and embracing my femme side; for all intents and purposes I am queer. This isn’t to say being femme is a prerequisite to queerness, but coming from a Pakistani background where gender roles and ideas of masculinity are stringent at best, the way I present myself isn’t technically “the done thing”.

The word, until very recently, was predominantly considered a negative one. In 2018, things have changed. To begin with, a number of mainstream musicians have proudly labelled themselves as such. MNEK, Kehlani and Years & Years frontman, Olly Alexander, all openly refer to themselves as queer. There’s entire branches of academia dedicated to queerness, queer art and queer theory growing in popularity at university. I’m even a member of a queer book-club.

So how and when did a homophobic slur — historically used to oppress entire generations of people — get reclaimed as the umbrella term for anyone who doesn’t fit into the heteronormative binary of sexuality and gender?

To properly understand the word “queer” and grasp just how much weight it carries, we need to go all the way back to the 16th century, to the first recorded use of the word. “Queer”, back then, simply meant something odd, strange or irregular. That’s not to say the act of being gay was any easier before words designed to oppress the gay community were created. While the Romans generally accepted gay relationships, by the 12th century being gay was considered “sodomy” — deemed a capital offence and punishable by death — as the word of The Old Testament spread and Christianity developed.

One of the earliest uses became popular northern colloquialism “there’s nowt so queer as folk”. Meaning, there is nothing as strange as people themselves.

It wasn’t until 1894, it seems, that “queer” was first used as homophobic slur — by John Sholto Douglas, ninth Marquess of Queensbury. This is where things become a little complicated. The Marquess had two sons, one of whom — Alfred Douglas — would end up romantically linked to Oscar Wilde. But the story begins with his other son, Francis. Francis worked as the private secretary to Lord Rosebery and the pair went on to have a romantic affair. After Francis died (his cause of death still remains unknown today) the Marquess, aware of his son’s gay love affair, blamed his untimely death on homosexuality.

“It wasn’t until 1894, it seems, that ‘queer’ was first used as homophobic slur — by John Sholto Douglas, ninth Marquess of Queensbury.”

In a fit of rage the Marquess wrote a letter to his other son, lambasting “snob queers like Rosebery”, therefore documenting the first recorded use of “queer” as a pejorative term. But unbeknownst to the Marquess, Lord Alfred was also involved in a gay romance with Oscar Wilde, evidenced quite extensively through the love letters they sent one another. When the Marquess eventually found out about his other son’s gay love affair, he made it his mission to take down Wilde and thus began Wilde’s trial for criminal indecency. The Marquess was successful and Wilde was found guilty of homosexual offences and sentenced to two years hard labour.

After the word reached the United States at the beginning of the 20th century, it began to grow in popularity as a homophobic slur. It contributed to the idea that LGBT people were the ultimate enemy, and gave people a licence to threaten and physically assault anyone they suspected of being so; the word reinforcing the idea they were “bad” or “crooked”.

Its reclamation began in the 1960s. In America, the gay rights movement had begun. Many of its activists identified as queer in an act of defiance and resilience to police brutality.

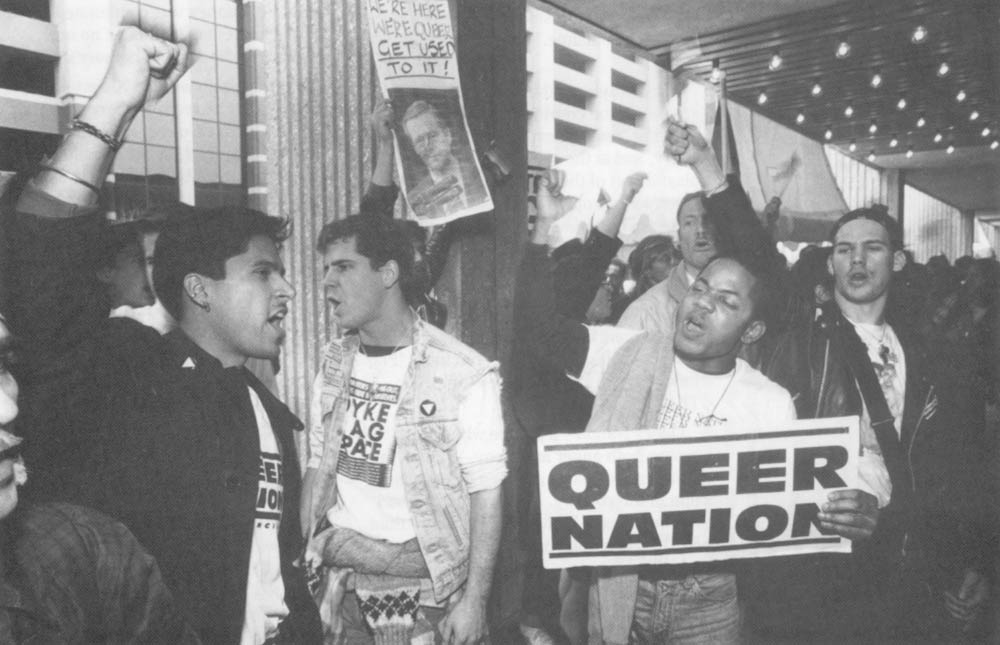

Banded together by anger at the government’s lax response to the AIDS crisis, Queer Nation was born in 1990. During the same year at New York Pride, the group issued a pamphlet called Queers Read This. It included what would later go on to be the building blocks to what we know now as queer theory, and it explained the historical origins of “queer” as a slur. It also outlined an initiative to reclaim the word as a way to fight back and take a stand: “Well, yes, ‘gay’ is great. It has its place. But when a lot of lesbians and gay men wake up in the morning we feel angry and disgusted, not gay. So we’ve chosen to call ourselves queer. Using ‘queer’ is a way of reminding us how we are perceived by the rest of the world. It’s a way of telling ourselves we don’t have to be witty and charming people who keep our lives discreet and marginalised in the straight world. We use queer as gay men loving lesbians and lesbians loving being queer. Queer, unlike GAY, doesn’t mean MALE.”

Armed with this new understanding and interpretation of “queer” and the power it carried, the early 90s saw fringes of the community actively identify themselves as queer instead of lesbian, gay or trans. They reclaimed the word as a middle finger to the heteronormative society that used it for decades to oppress them.

“The early 90s saw fringes of the community actively identify themselves as queer instead of lesbian, gay or trans. They reclaimed the word as a middle finger to the heteronormative society that used it for decades to oppress them.”

It wasn’t until the new millennium that “queer” was first used in mainstream media and pop culture in a positive context with the release of the UK show Queer as Folk in 1999, and its American incarnation, released a year later. The show followed the lives of gay men living, loving, working and fucking, with an honesty that had rarely been seen. In 2003, Queer Eye for the Straight Guy made its debut, with five gay men employed to improve the lives of a different clueless straight man each episode.

Both shows, drastically different in content, style and production, used “queer” as a blanket term for anyone who didn’t identify as heterosexual. The characters were shown as normal, acceptable and fabulous, but, it must be noted, queerness was represented by wealthy privileged white men — a group that, in many ways, had already won the most acceptance and were least likely to identify with the term. It’s a condemnation that still plagues many TV and reality shows today, including Looking, EastSiders and Netflix’s Queer Eye, that claim they represent all variations of queerness. Ru Paul’s Drag Race is a worthy exception of this critique, but as the show’s mainstream popularity has skyrocketed in recent years, its portrayal of queer people has come under fire.

Despite a concerted effort by large pockets of the LGBT community to take back the word and reintroduce it as a sign of power and resilience, for many, particularly older gay men and women, the word “queer” still remained nothing but a nasty slur that was shouted at them in the school playground, or on the street by random strangers.

A prime example of just how contentious the word can still be, even after its apparent reclamation, was The Huffington Post’s decision to rename its ‘“Gay Voices” section “Queer Voices” in 2016. Preempting the backlash, the editorial team published an essay explaining their reasons for the name change — admitting they were hesitant due to the word’s history as a slur, but that they felt strongly that “queer” was more inclusive and representative of all members of the community.

“In a world where more young people are identifying as gender-fluid, non-binary and trans, the word ‘gay’ just doesn’t do enough to explain the grey area gender and sexuality fall into.”

It seems that in 2018 “queer” is in the midst of a revival. Many out and proud kids are taking hold the word and tagging it in their selfies, their Twitter bios, their dating profiles. And, in a world where more young people are identifying as gender-fluid, non-binary and trans, the word “gay” just doesn’t do enough to explain the grey area gender and sexuality fall into.

As with any slur that’s reclaimed by an oppressed group, the question of who is allowed to say it still draws blanks today. Is a straight person entitled to ask me if I’m queer? Just earlier this year rapper Offset, one third of Migos, came under fire for using “queer” in a verse for the group’s song Boss Life. He later explained on his Instagram account his use of “queer” was intended to refer to the word’s original meaning of weird or strange, and not meant as a homophobic slur. Clearly context plays a massive role in how it’s received and used, which is probably why some LGBT people avoid using the word altogether.

In an era of heightened sensitivity, in which people are trying to open their minds and expand their social consciousness, there has been an effort — not quite on the scale of Queer Nation’s pamphlet in 1990 — to reclaim other homophobic slurs in hopes of taking back the power they once had over us. These words — one rhymes with “maggot” and the other with “bike” — are routinely used across social media ironically or in memes in a bid to change their meaning and become terms of affection. Just last week Stranger Things star Millie Bobby Brown deleted her Twitter because people were making memes of her suggesting she was a raging homophobe, attributing anti-gay slurs and ideas to her in a poor attempt at satire. For that reason alone I’m not quite sold on reclaiming terms still fuelled by such hate, particularly when actual homophobes and hate groups, such as the Westboro Baptist Church, continue to use these words.

Truth be told, as a community we’re probably never going to agree when it comes to “queer”, and that’s fine. One of the great things about our community is our right to choose how we identify ourselves without judgement. But I do think it’s crucial that we acknowledge and accept “queer” as part of our lexicon, even if you don’t personally subscribe to it. It’s embedded in our history and gave generations of LGBT people before us the courage to stand up and fight for the rights we often take for granted today. When Queer Nation took to the streets at New York Pride in 1990, they chanted “We’re here! We’re queer! Get used to it!” at the top of their lungs, and it’d be a shame for our own community to be guilty of silencing them decades later.