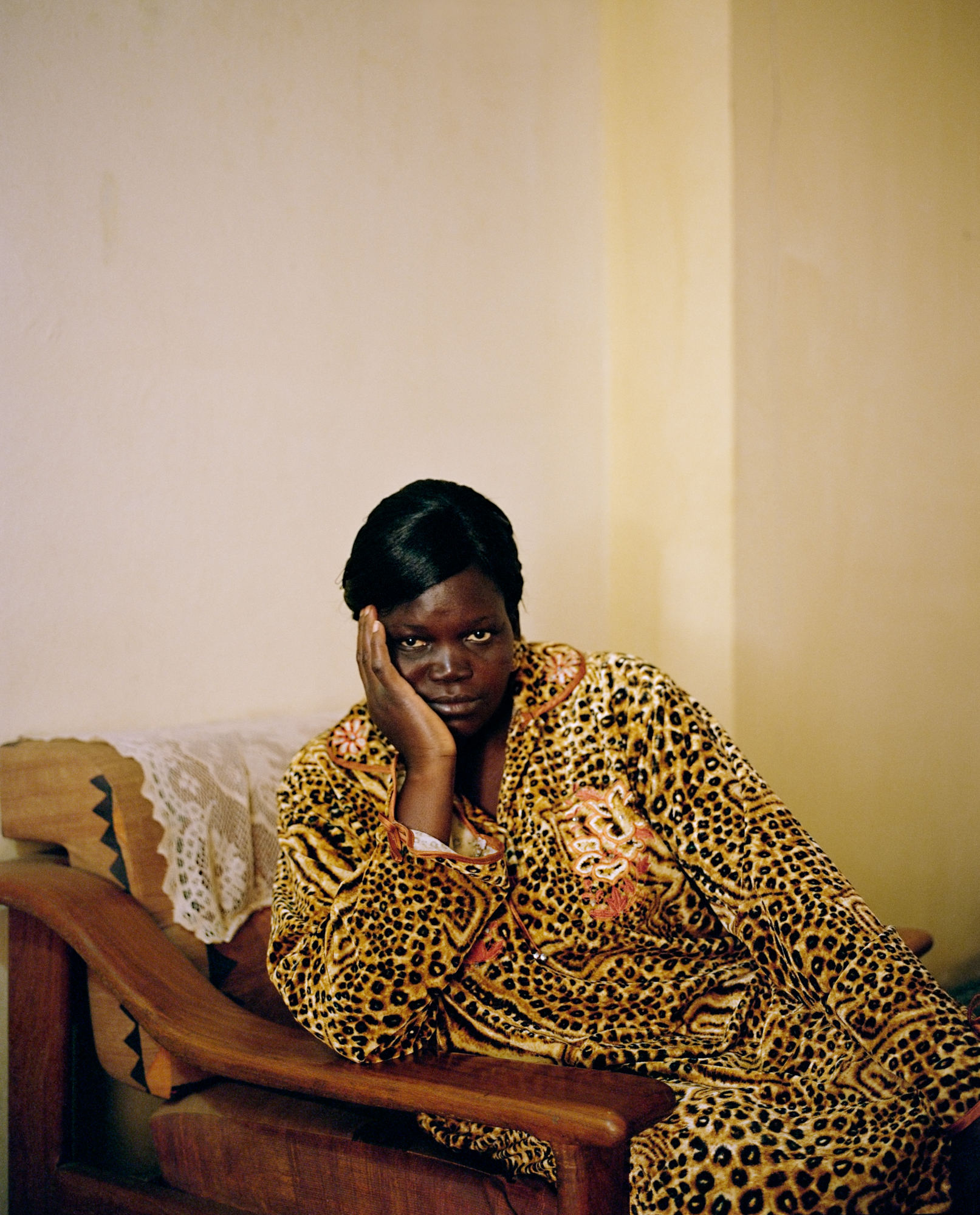

Émilie Régnier has long been a nomad. The photographer, Canada-born and Gabon-raised, today toggles between Africa and Europe. She came into her own through the series Hair, featuring snapshot-style portraits of women in Abidjan, and then Leopard, a global chronicle of people with an acute connection to that unmistakable speckled print — and everything it represents, from luxury to ferocity to kitsch. Leopard includes a professional impersonator of a former Congolese dictator (whose sartorial signature was a leopard hat), French actress Arielle Dombasle (posing alongside a taxidermied creature in Paris’s Musée de la Chasse et la Nature), and a Texan tattoo artist (whose epidermis is completely inked in leopard print). Some images feel like studio portraiture, others like street photography. Given this, Régnier’s work has resonance in a lot of different contexts, and her series have been shown everywhere from the Bronx Documentary Center to the Photo Vogue Festival.

We spoke to Régnier about Diane Arbus, seeking subjects on the internet, and the complexities of representation.

How were you drawn to photography?

My first camera was given to me by my grandfather, when I was six or seven; it was a Polaroid. I got obsessed. When I was 16, I bought my first semi-professional camera. The arts are difficult to embrace — I studied visual arts, freaked out, and took a more traditional path. I felt you should do “law” kinds of jobs. I studied political science, philosophy, history. And then one day I freaked out again and decided to become a professional diver. I realized, while I was taking a diving class, that I was claustrophobic. I was like: I’m screwed!

I went to Australia, where I met a guy who was a photographer, and I fell back into my love of photography. I returned to Montreal and studied commercial photography, like how to light a bottle of olive oil. I became a photo assistant for two years, on commercial and fashion projects. My dream was to be war reporter; I moved to Senegal to do that. It didn’t work out very well; I couldn’t really deal with a combat situation. From then, I started to embrace beauty. I don’t know if you can say I’m a fashion photographer, I’m an art photographer… I think photography is a way to be very present with what you’re doing. I’ve been to so many places, I want the rest of the world to be able to relate to others, beyond judgment. This is what my work is trying to do.

Is your Leopard series ongoing?

It is. There will be new portraits — only four, but major people, who have a very deep relationship to leopard. Every person I photographed was a striking representation; I’m not interested in day-to-day. When I was in South Africa at this Zulu gathering… there’s a spiritual link to it. When I saw Larry, I thought: this is not only a story of print, it’s a story about this person. I was like, hey dude, I’ve seen your face on Google Images — would you like to be part of this? And he was like, ‘Sure!’ It took me like six months to find the money to fly from West Africa all the way to Texas.

I saw on Instagram you were looking to contact Jocelyn Wildenstein [the socialite known for getting surgeries to make her look catlike].

She’s such an interesting one — she has such a strong relationship to the feline. I would love to know why, but unfortunately I never got through to her.

Are there other ways you’re thinking of perpetuating the series?

I’m not going to do a zebra project. But I receive a lot of photos — people see leopard and think about me. Over the years, a friend in Bamako sent me a motorcycle; a friend in Boston sent a girl in a super-beautiful leopard dress. I would love to start an Instagram of all the photos I receive, from Los Angeles to Kinshasa: a participatory project. It’s another way to connect people. I’d love to do a book — to work with a historian and a fashion historian, because there are stories I’m barely touching on. It goes much deeper, once you look in archives and do research.

The conversation around beauty and representation has been changing. How has this, in turn, shifted the discussion around your work?

It depends on which work. For the project I did on hair, I heard a lot of beautiful comments — but also a lot of hurtful comments, and not only from Western society. There was judgment about why black women want to wear their hair straight when it’s in fact part of the heritage of colonization; some women have been forced to hide their natural hair since slavery. What I now tend to notice is, the women I portray — born in the 80s or 90s, influenced by Rihanna or Beyoncé — want their own definition. Colonial hair was imposed, but then reinvented: women re-appropriated it for themselves.

Leopard gets it the other way around. It didn’t only come from Africa — it came from Asia, Eastern Europe — but when Christian Dior used a print called jungle, the dress was “The African.” Before him, leopard was seen as tacky and cheap! Now it can be seen as sexy and savage. It’s not one thing; it can be all of these things. We reinvent. Those changes are fascinating to me. What’s great is that the work brings up questions. You like it, you don’t like it — let’s talk about it. The matter of representation is very important to me. I went to see Black Panther with my little sister — and I have a lot of criticism for the film — but when I got out of the movie… it’s what I lacked through my teenage years! To find myself attractive. Like, we’re not only gangsters or prostitutes. We can be literally saving the world. That’s amazing! So it’s shifting, in a good way, but it will take years… Maybe when there are as many white nannies pushing black babies as black nannies pushing white babies.

Which photographers have been meaningful to you, in terms of addressing representation?

Lorna Simpson. Just like… [smiles]. Omar Victor Diop’s series Diaspora, in what it shows, what it says. A good friend, Hélène Jayet, who is based in Montpellier, did a project for years on hair, but natural hair. She was having this public exhibition in Paris and people said to her: ‘why would you show us like that?!’ But she’s changing boundaries with her work. My biggest influence is Diane Arbus. She touched on representation — not necessarily black, but marginalized identities. Every time I’m stuck on a project, I refer to her work. I discovered Lee Miller later, and was really fascinated by her life. I love the work of Zaneli Muholi. She uses her body for activism and gender, which I think is fantastic.

You’ve shown internationally. Have there been very different reactions to your photos?

I’ve shown in Dakar, New York, Paris… those aren’t controversial places. We’re planning an exhibition in Durban — I did portraits there, one of which is included in the series — where it’s majority Zulu, the reaction could be interesting. Because to them, leopard is the emblem of the royal family. So I really look forward to see how people will relate. One of my images is a painting of Mbutu, the former leader of the Congo for thirty years, and the other is a portrait of Samuel Weidi, who impersonates Mbutu. He’s kind of a local celebrity: he goes on the radio, he does educational programs. But I haven’t shown in Kinshasa — I would love for the show to go there. I would love to know people’s reactions.

What other projects are you working on?

I’m working on a DNA project, but it’s a very slow process. I did a DNA test last year; I was connected to 1224 people who share segments of my DNA. So I contacted all of them, and 40 of them got back to me. What I’m doing is a self-portrait where I cut myself in two and also halve people who share part of my DNA. So family and relatives, and then total strangers that are part of me. Through this platform, they are all white, but I’m gonna use another platform that is for African ancestry, so I can connect to different roots, like what villages my ancestors came from before the slave trade. It’s to challenge this idea of perception: what is white? What is black? It’s super ambitious. But globally, patterns can unite people.