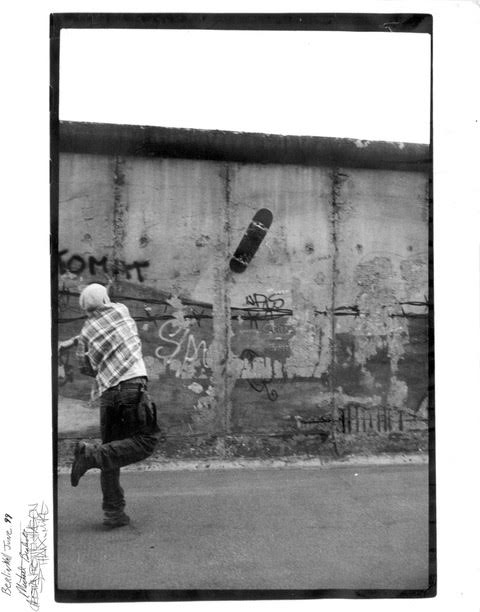

Berlin has long been a destination for people in search of subcultural wildlife. Take, for example, the city’s skateboarding scene, which today is as vibrant as ever. Last year, TransWorld Skateboarding dubbed the city “the new Barcelona”, i.e., the new European mecca for skate tourism. What many visitors don’t recognise, however, is that the history of skateboarding in Berlin is as fascinating as the history of Berlin itself — the development of the skate culture over the past three decades was just as influenced by Cold War politics. Skaters today cruise from east to west with ease, but 30 years ago were separated by a wall. Like the city, skate history, experience and style was split. Members of the generation of skaters who “ollied the wall” are still formative figures in the scene today.

Marco Sladek, Freie Welt Cover courtesy the Skateboard Museum Wall Ride exhibit

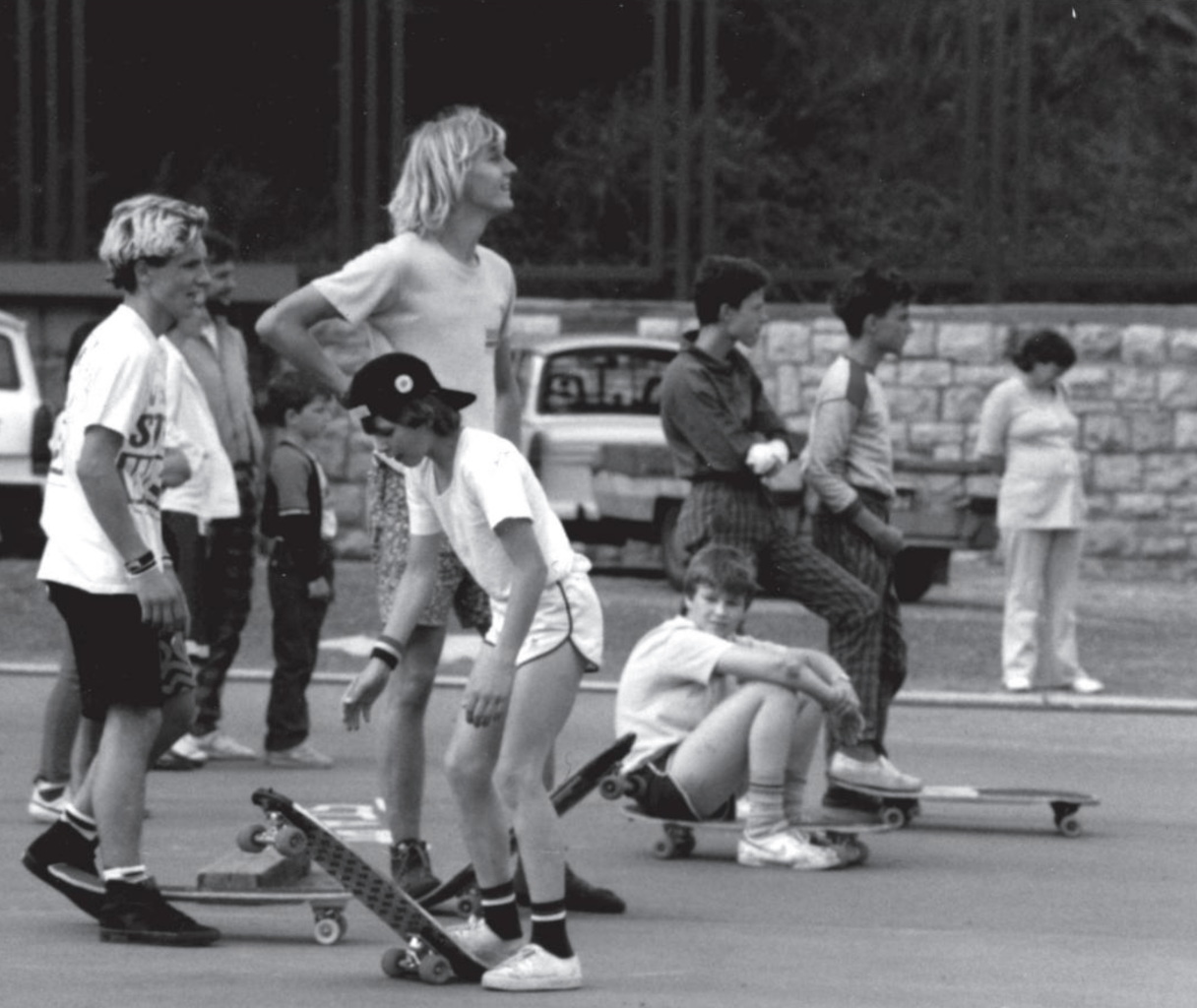

East German artist and skater Christian Rothenhagen has lived in two cities and under two political systems without ever moving. Growing up in the GDR in the 80s meant limited access to the western culture, media and products — a limitation that bred DIY spirit in its purest form. East Berliners like Christian, however, lived in the closest possible proximity to West Berlin, a capitalistic city floating like an island in the socialist East. With only a wall between them, East Berliners could easily finagle antennas and watch western networks. Christian was first introduced to skateboarding via western TV and more specifically, the iconic 1980 filmSkateboard Madness. A newfound fascination with skating led Christian to build his first board by combining a plank of wood and two halves of roller-skates. It took three years of wipeouts and board carpentry before Rothenhagen had the courage to join the small community of skaters in East Berlin, who rode in the city’s most central and public plaza, Alexanderplatz. Skaters treated Alexanderplatz as a stadium for their craft, where they practiced alongside Easterners with an equally western hobby, breakdancing. Those familiar with the modernist architecture of East Berlin can understand why it’s a skaters paradise: a utopia of smooth concrete, wheelchair ramps and buckets of open space.

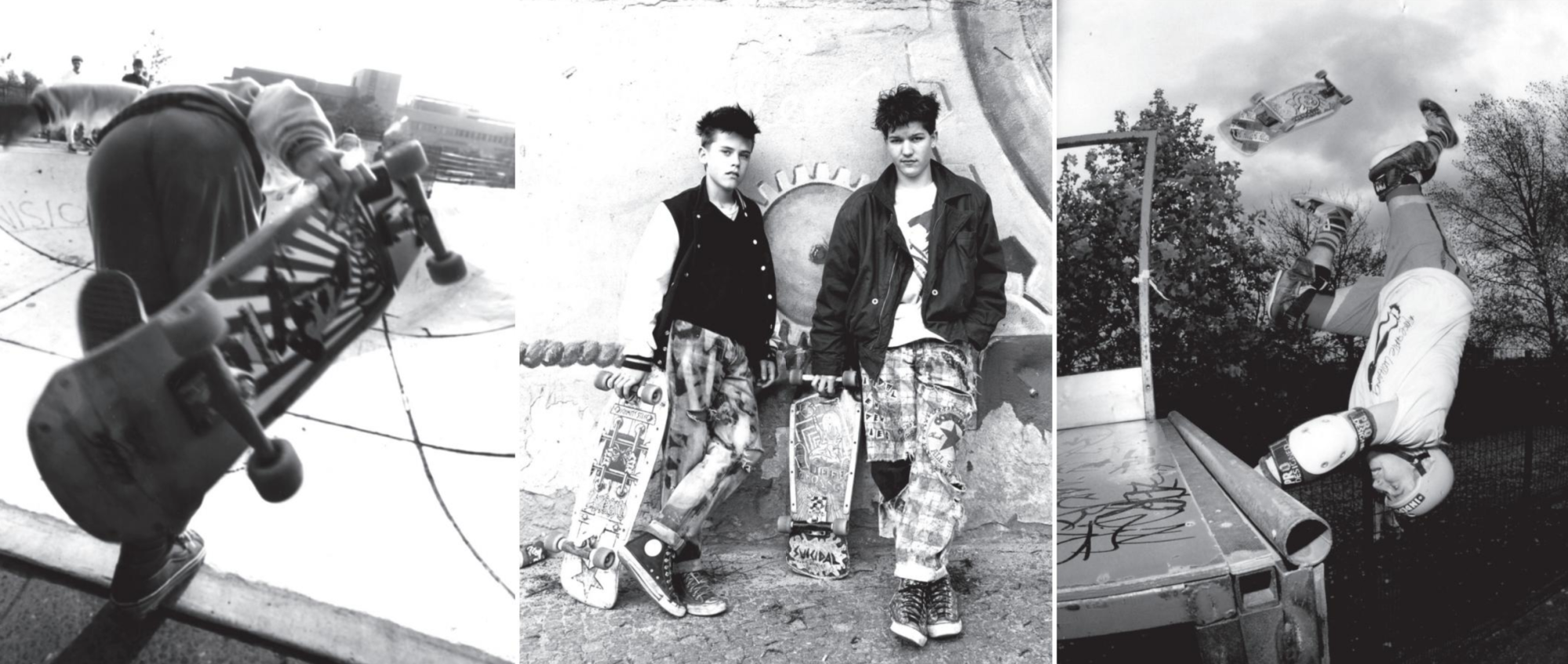

Christian recalls the warmest of embraces among the community despite the intimidating circumstances, even from the GDR’s most famous skater, Marco Sladek (who helped him learn to ollie on his second day at Alexanderplatz). Marco emerged as a kind of poster boy for skating in the GDR; in 1988, he was even featured on the cover of the GDR magazine ironically namedFreiwelt (free world). Christian and Marco’s squad of skaters went on to spend virtually every day together — crushing beers, building ramps and transforming their brutalist, grey atmosphere into an idyllic urban playground. Their lack of access to equipment and gear was partially remedied by skaters from West Berlin, who smuggled them used boards, shoes and trucks as an act of skater solidarity.

Another challenge in the East was public perceptions. “Skateboarders were known as left wing, different, alternative people. The police didn’t know what to do with us, it wasn’t an official sport that could be harnessed for competition. We didn’t fit into any form or category. We were just kids having fun,” says Christian. He also recalls his gang pissing off residents with their noisy pastime, having water thrown on them, being closely watched by government representatives, and even being chased by the occasional nazi and hooligan. However, separation from West Berlin did have its benefits. With no skate brands, companies, sponsorships or competitions, skating was about one thing: fun. Skate historian Jürgen Blümlein (of Berlin’s Skateboard Museum) explains this time elegantly, “You started skating because you found it to be a thing which gives you something back: a community of like-minded people. There was no end goal.”

On the other side of the wall, there was photographer Alex Foley, one of the West Berliners who remembers going on skate tours in the East and meeting GDR characters like Christian and Marco. In the late 80s in the West, skateboarding was more or less established. West German skater Titus, who today is credited with “bringing skating to Germany”, had already begun opening skate shops around the country and developing the industry. Meanwhile, huge blockbusters like Back to the Future brought skateboarding to the forefront of Western consciousness. Foley remembers being impressed by Easterner’s creativity and their dedication to the sport and attitude, despite limitations on resources. “Skating was an American thing. It wasn’t something their government wanted to see. You had to have balls to skate in the GDR,” explains Foley.

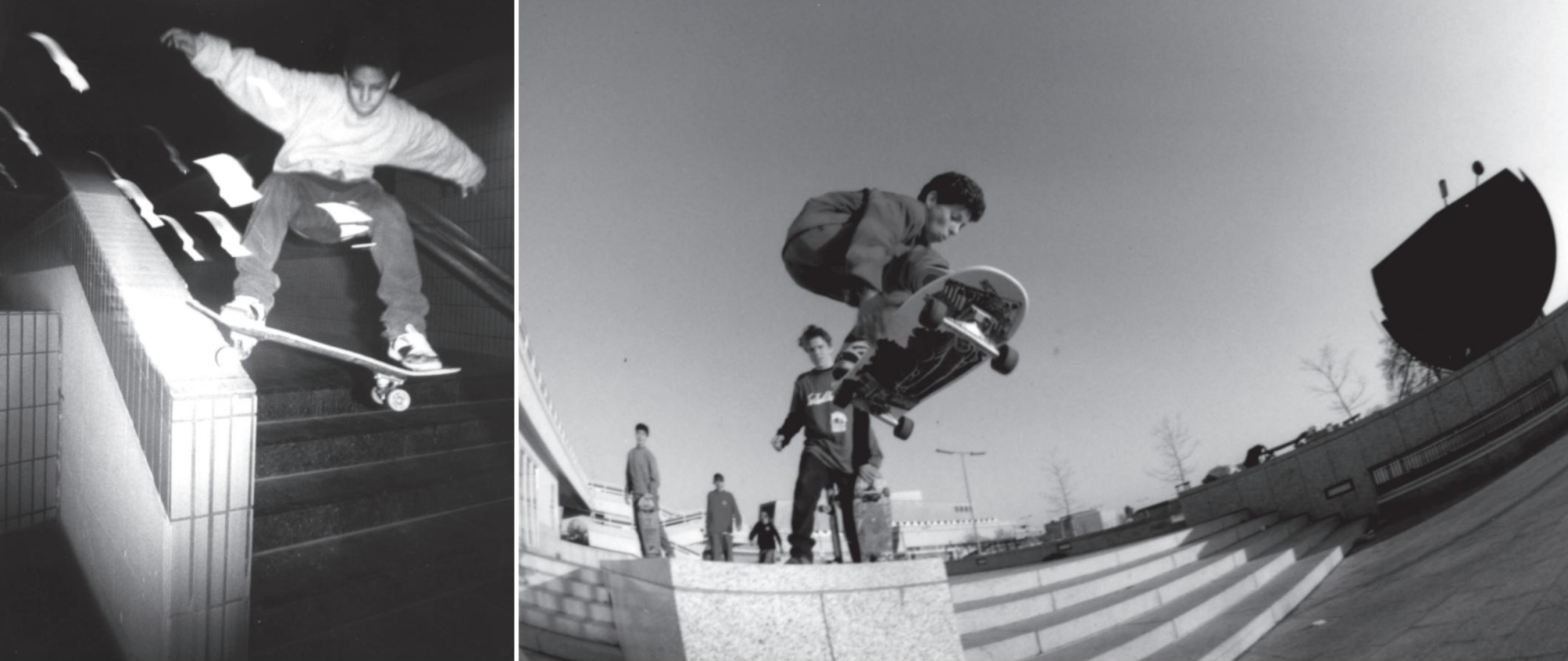

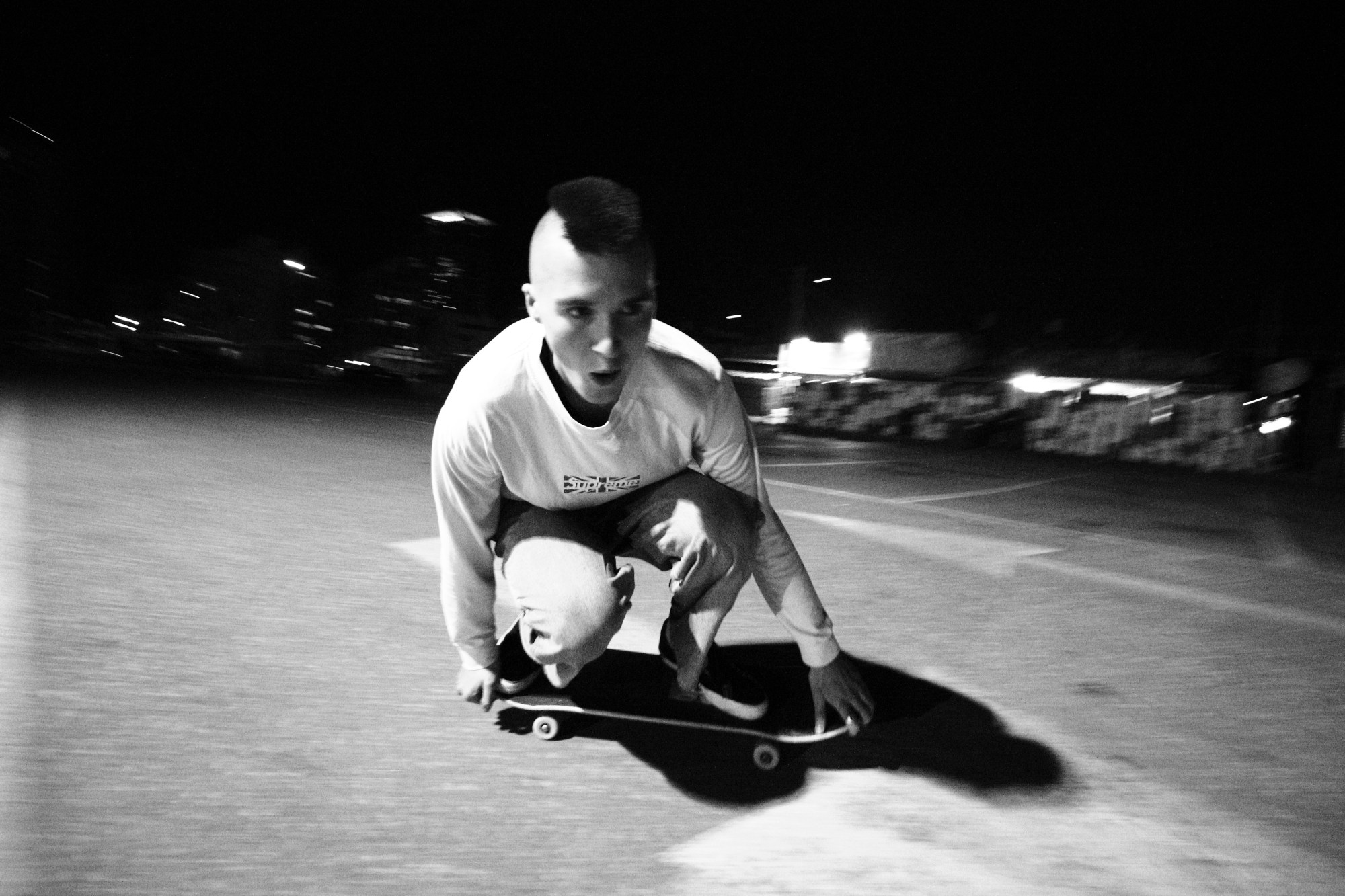

Despite living in opposite spheres of influence and their completely different styles, skaters from the West and East felt genuine comradery. After 89, the two skate scenes merged. “When the wall came down, we got to explore a whole new city by board. These were amazing times of course, skating those Russian monuments in marble and the East German government building, Palast der Republik. Berlin was the only place where you could really feel the reunification of two cities.” The 90s are what both Christian and Alex refer to as “the golden days”. The fall of the wall meant, for skaters, double the terrain and double the friends. Foley commemorated the era via his other passion, photography. Foley spent his years documenting the colorful characters in his world and in particular, his friend, legend, Sami Harithi, who to this day is recognised as one of the country’s most influential skaters. Often referred to as “too good for his own good”, Sami’s talent meant a sacrificed childhood and years of intense pressure, representing the darkside of commercial influence on the sport. Sami’s formal skate career is long over but he continues to frequent Berlin’s parks — just for the fun of it.

While Christian has built a lively career as an artist (whose work is influenced by his skate heritage), Alex is now an owner of Berlin’s best skate shop, Civilist. While skate fashion is applauded by the fashion world today, that wasn’t the case in Christian and Alex’s days. “I still remember all of the times I got shit for wearing my baggy pants in the early 90s,” says Christian. According to Alex, “you could point out every other skateboarder in the city, just by the way they dressed. Baggy pants, beanies in the summertime. Today you can’t say that at all.” Despite existing in the age of ultimate skate hype, where Thrasher T-shirts are ubiquitous, Civilist is clearly by skaters, for skaters. Fashion is only a small part of its significance in the Berlin skate scene, it’s a communal space that’s become central to Berlin’s current generation of skaters. “I’m at a point now where I can give something to the kids of the next generation. I can help give them a chance or an option to make something out of the skateboarding scene, like I did,” says Alex.

Intergenerational relationships are keeping the spirit of Berlin’s skate heritage alive. Berlin native Steffen Grap and his crew of friends who skate for Civilist count Alex as a mentor. Grap has emerged as a prime example of “making something” out of his skating. His analogue portraits of the “Civilist gang” have gartered him attention from the art and fashion scenes for their romantic candour. Following in Alex and Civilist’s footsteps, Steffen recently launched his own clothing line, Champagne Towers. However Steffen, like his predecessors, expresses a bit of dismay at the changing culture of skateboarding. “I see all of the little skate kids and they’re not starting because skating is fun. They’re skating to get a sponsor, or to be the next pro skater. It just feels wrong,” he says. Skateboarding’s recent explosion, perhaps best illustrated by the decision to include skateboarding in the Olympics, means the stakes today are higher than ever. Nike, adidas and other major brands loom over young skaters, who put their literal limbs on the line in hopes of achieving recognition. “I’m so grateful to have the times I did in the 90s. I realise now how precious our outlook was,” explains Christian. Though if there’s anything Berlin breeds, it’s authenticity — and if there’s hope for any skate scene to stay true to the roots and attitude of the sport, it’s not farfetched to predict it’s this one.