Social media has helped under-highlighted narratives receive the attention they deserve. Platforms like Instagram and Tumblr have been revolutionary for minorities, allowing the LGBT community and people of color to form artistic communities. Consequently, emerging black photographers have carved out a unique space for themselves. It’s uplifting to see the wide array of black identities, experiences, and beauty these young creatives are presenting to the world. They span the globe — from New York to Belgium to Kenya — and allow for a more complete spectrum of the black diaspora to be presented.

Black joy runs abound in these photos. Myles Loftin presents a refreshing illustration of black boys giggling and enjoying life while wearing candy-colored hoodies. The photos illustrate that black men in hoodies don’t equate to violence and crime. And photographers like Kamau Wainaina, Yannis Davy Guibinga, and Miora Rajaonary paint a more refreshing vision of Africa, one that is full of pride, culture, and prosperity. Some of these photographers do not directly touch on blackness at all and this is important too. Brussels-based teenager David Uzochukwu creates beautiful sci-fi worlds in Adobe Suite. His ornate fantasties serendipitously led to a close artistic relationship with FKA twigs. Meanwhile, fashion photographers Davey Adesida and Ekua King shoot intimate, quiet portraits of models and celebrities that add some much-needed diversity to the field.

Here are ten black photographers to keep an eye on in 2018.

David Uzochukwu

David Uzochukwu is only 19 years old. Impressively, he’s already established a career that rivals photographers with many more years – or even decades — on him. The Austrian-born, Luxembourg-raised creative captured FKA twigs for a Nike campaign and later collaborated on a zine with her. On top of that, he’s shot celebs like Pharrell Williams and Ibeyi and worked on a campaign for Missoni x Pigalle. Not bad for a teenager who taught himself how to use Photoshop in his bedroom.

“I go for wonder and vulnerability,” David says of his aesthetic, which commonly includes fluorescent skies, contorted bodies, and alien references. “I’m just trying to get rid of emotional baggage. It feels cleansing.” David’s fantastical self-portraits feel like they were shot on Mars. There’s a photo of David, nude and enclosed in a rose-pink bubble, floating in the sky. It’s like a fetus — sensitive and pure — protecting itself.

David started taking photos at 11 years old when he picked up his mom’s camera during a vacation. (“I was gone for good right away after that.”) Hearing David talk about living in small, isolated towns as a kid gives a powerful context to his photos. “I played outside when I was younger,” he says. “My grandfather seemed to know everything about nature and wherever we were there was a lot of nature around. Growing up in those isolated spaces meant feeling very exposed as a minority. A bit of all that is in my work today.” It becomes clear: David’s baroque, sci-fi images are about a teenager feeling alien in his own home.

Myles Loftin

“I’m interested in exploring how blackness is nuanced and shapes identity,” 20-year-old Myles Loftin tells i-D. “But, most importantly, I want to explore the inherent beauty in being ‘unapologetically black.’”

The Parsons student’s colorful Polaroids of black joy are just as vibrant as his Kool Aid-red hair. His PoC subjects are photographed in front of punchy backdrops — ranging from clementine-orange to banana-yellow — and they seem to exist in a permanent state of fun. Myles opts for smiles more than he does cold smolders. And the vision of blackness he captures is one that includes varied forms of gender expression, vulnerability, and boundary-pushing fashion. His photo of four black boys playfully piled on top of each other and immersed in pure glee specifically aims to “decriminalize the societal image of black boys and black men dressed in hoodies,” Myles shared in an emotional post on Instagram. “Photography has the unique ability to give importance to its subjects,” he says. “When you decide to photograph someone or something, you’re telling the world that this thing matters and they should pay attention to it”.

Joy is a fleeting emotion. So it makes sense that Myles uses a Polaroid camera, with its fast-processing film, to capture his subjects. It allows him to live in the moment. “The unique experience created between the subject and the photographer is what I find really interesting about Polaroids,” he says. “You’re able to take a photo, develop it in a matter of minutes, and share it with the person to view and keep.”

Laura Alston

In a way, Laura Alston’s series As Laid As It’s Tied feels like vintage family photos shot by a department store photographer. And that’s a compliment. We promise. What Laura manages to get at through this aesthetic is black subjects proudly displaying their identities in a format that typically strives to erase them. When it comes to department store photos, families of color tend to shed their everyday clothes in favor of suits and ties and fancy dresses. But the young adults in As Laid as It’s Tied wear their durags and jean jackets and feel like a family that has invented its own rules. Consequently, the subject’s most authentic selves are captured. Add the complex racial politics embedded in durags and these portraits take on a radical, subversive air.

“I wanted to show appreciation in regards to how durags have existed in our hair traditions for years,” Laura Alston tells i-D, speaking on the layered significance of the head wrap. “Whether for function or fashion, black hair rituals — like wearing durags — are beautiful not only because they shape one’s hair into a desired look, but also because of the process it took to get there.”

Laura says she first started using photography as a creative medium during her freshman year of college. “I always carried around a disposable camera and would take photos of friends, artists, and events,” she says. “Then I’d wait months before developing the film. The delayed gratification and nostalgia was so refreshing to me.” Since then, the 22-year-old has gone on to receive a degree in visual arts from Columbia University and found the artistic brand Afrobaby Movement, which focuses on “celebrating individuality through natural hair, art, and hip hop.” The emphasis on creating authentic creative expressions of blackness is important to Laura, as she seeks to illuminate the overlooked facets of our experience. “A lot of media commodifies black trauma and tragedy, so I feel it’s necessary to create work that celebrates black joy and wellness.”

Yannis Davy Guibinga

“When stories about Africa and its people are told, the diversity of identities and experiences within the African diaspora is something that’s often missing,” Yannis Guibinga says. The Gabonese photographer has made it his mission to help correct this monolithic view of Africa. He delivers a ebullient vision of the rich continent: oversaturated primary color palettes, stunning models, and lush gardens. His photos feel futuristic, in a way. The architecture is sleek and elegant, his models wear cyborg-esque shades, and the sky is a an otherworldly, bottomless royal blue.

“As an African artist, I understand the necessity to use my art to contribute towards changing the way people think about the continent,” Yannis says. “I’m interested in capturing people who sit at the intersections of different identities and show that while their African experiences might be slightly different, they are just as authentic and valid.”

Yannis says he became interested in photography during high school “out of boredom and a way to find something to do on the weekends”. Luckily, his casual interest blossomed into a colorful lifelong passion. His favorite thing about photography is “the ability to tell stories about people, their identities, and their experiences in the most accurate and realistic way possible”.

Davey Adesida

The soft-as-a-whisper blues and grays in Davey Adesida’s portraits gift a chilling intimacy to his images. His clean color palettes and sets make his photos refreshing moments of quiet in our crowded Instagram feeds.

Davey’s tranquil approach is thanks to his enduring love for classic Hollywood films. (In fact, he says they’re the reason he got into photography.) Davey is in his 20s, but describes himself as an “old soul”. So, of course — just like his favorite films — he shoots all of his photos on analog film. “I use a lot of Kodak,” he says, elaborating on his love for the antiquated format. “It’s nice for skin tones.”

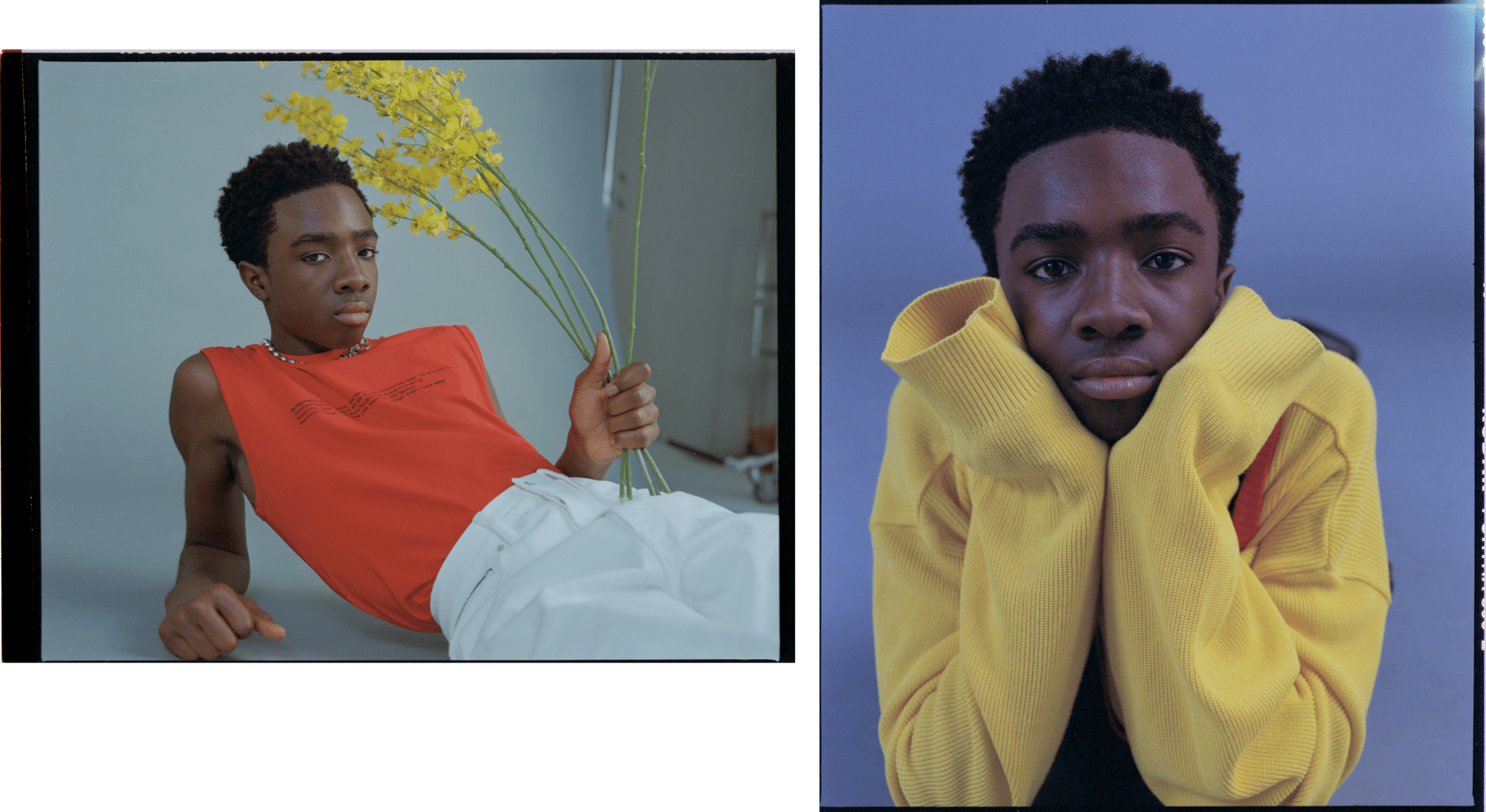

Raised in Nigeria, Davey lives in New York now and has photographed emerging young creatives like the fashion collective Vaquera, podcast host Dylan Marron, and Stranger Things star Caleb McLaughlin. When asked what attracts him to his subjects, Davey’s response is just as poetic his photos. “ Could be anything,” he says. “Legs, face, movement, kindness in their eyes…”

_xST

Philadelphia-based photographer _xST (whose real name is Shawn Theodore) highlights the mesmerizing magic of black skin in his high contrast images. His models’ skin are a supernatural midnight-black — their facial features completely obscured by the darkness — and stand in front of complementary bright backgrounds. Dark-skinned blacks have experienced stigma and prejudice since the beginning of slavery, making it powerful to see _xST crank up the shadows on his images and turn his models’ skin the blackest black possible. It’s a middle-finger to harmful Euro-centric beauty ideals.

“My use of silhouettes is a tribute to the works and influence of the Harlem Renaissance painter Aaron Douglas,” _xST explains of his distinct silhouettes. “His theory was that the ancestral arts of Africa were relevant, meaningful, and above all a part of our black heritage. And we should use them to project ourselves.”

_xST calls himself an “Afromythologist”. He explains the term as “someone who questions official histories, and explores the radical possibility of alternative narratives through the creation of a missing, yet necessarily specific, African American mythology.”

_xST hopes his use of Aaron Douglas’s aesthetic will be embraced by other black photographers. “In my opinion, there is no greater way to command the power of black identity than through the use of, and adaptation of, the silhouette,” he says. “It’s a gorgeous way to interpret the meaning and feeling contained in black expressionism, with its purpose being an invitation to bask in the wonder of it all.”

Kamau Wainaina

One of 20-year-old Kamau’s most powerful memories is discovering vintage photos of grandparents and being amazed at how “freshly-dressed, empowered, and modern” they were. “The fact that was such a huge shock to me is pretty fucked up,” he says, speaking on how the media has misshapen his perceptions of his Kenyan culture and history. “I don’t think we realize the power that visual representation and misrepresentation has on people.”

This has inspired Kamau to provide a more personal vision of his home. The current NYU student shoots warm, grainy pictures of his Kenyan family and friends that beautifully merge fashion photography with documentary. In fact, Kamau says the reason he loves photography is because of its ability to “simultaneously capture our world and likeness, but also create and sustain worlds that could never exist in reality”. His naturalistic photos illustrate how black people’s lives are brimming with photo-worthy moments. No studio lighting or photoshop is required. “It makes me cautious of how easily we cheapen the portrayal of others by using them for our images,” Kamau shares. “Aestheticizing their pain and commodifying their existence. I never ever want to do that.”

Kamau typically shoots on a medium format camera — using vivid films like Fujicolor 400 and Kodak Portra 400 — but says he finds himself shifting to digital lately. And it’s not because his love for analog photography has disappeared. (“Honestly, the expensiveness of the film helps me focus so I’m more patient and purposeful with each photo.”) It’s because film rolls are so hard to find in Kenya. “In Nairobi, finding film is like unicorn hunting,” he says of the challenge. “And developing it is near-impossible.”

Regardless, Kamau is sticking to his goal of shifting the world’s perception of Kenya. “It’s frustrating to see how many photos of Kenya and its people come from external parties who misrepresent us through only looking for a certain image that sells.”

Ekua King

Being a black photographer shouldn’t mean your work always has to be centered on blackness. The expectation can be limiting. Ekua King’s photography challenges this. While the past i-D contributor frequently shoots black men, the real focus appears to be on capturing the jubilant buoyancy of young adulthood. Shirtless six-packed boys play soccer, off-duty models are shot eating McDonald’s, and young men are seen loitering around LA on basketball courts and street corners. “I don’t only shoot black men,” Ekua, who comes from Jamaican heritage, says. “But they are the subjects I feel most connected to and intrigued by within my work. The way a black man moves, I find captivating. The black male image is a subject I’ve been visiting and revisiting since my final project at university.”

Ekua says she loves when her photos are able to stand on their own and tell a complete story. She finds it hard to shoot a subject she hasn’t formed a personal connection with. This is obvious through her gentle approach. In a diptograph, she focuses on a young man stretching his long arms and lean body in captivating ways. It’s deeply intimate. The photo feels more meticulously analytical than it does sexual. And Ekua’s caring gaze is purposeful: “The associations of negativity associated with black men compels me to produce work that challenges stereotypes and presents honest, empowering, and positive representations.”

Myles S. Golden

“I love the indexical nature of photography,” NYU student Myles S. Golden tells i-D. “Every photograph holds a date in its fibers and there is a hauntingly beautiful aroma to that. When I look back at photographs of my family, especially ones of my parents and grandparents from before I was born, I am in awe at how many histories are carried within each frame.”

The gender non-conforming femme artist stages highly conceptual self-portraits that explore gender in relation to blackness. Myles is fearless in their photos. In the powerful black and white series, A Dead Name That Learned How to Live, examined the fight for black liberation. Myles uses nooses and full-frontal nudity to illustrate the darkness forever embedded in the legacy of slavery. “I primarily use black-and-white film because I believe the complexities of blackness and the architectural multiplicities of black bodies are not obscured within black-and-white film,” Myles explain. “Illumination, erasure, and shadowing are thematic reverberations that have circled around black bodies throughout history. I use these parallels within my work to tease out what black history is and has been.”

Miora Rajaonary

Originally from Madagascar, Miora first started taking photos when she moved to South Africa and “started questioning my identity as a woman”. She considers photography therapy and attempts to find answers about her subjects’ interiors through her photos. “And a little bit about myself, too, I guess,” she admits. Mirora’s obsession with exploration is most obvious in her documentation of the punk scenes in Soweto (a township in Johannesburg). South African young adults are photographed skateboarding, rocking out, wearing KISS-esque makeup, and, well, simply enjoying life. “The images of the very dynamic, resourceful, creative young Africans are still a scarcity,” Miora says.

Miora is not involved in Soweto’s punk scene, but there is a lot she admires about the subculture. “I related to them, because they did not do what they were expected to do as young black men,” she says. They are reclaiming a music associated with white people, in a country when the population and culture are still highly segregated, and doing their own thing without caring about race or rules. It was surreal and very liberating to capture that, especially here in South Africa.”

miorarajaonary.photoshelter.com

All images courtesy of photographers