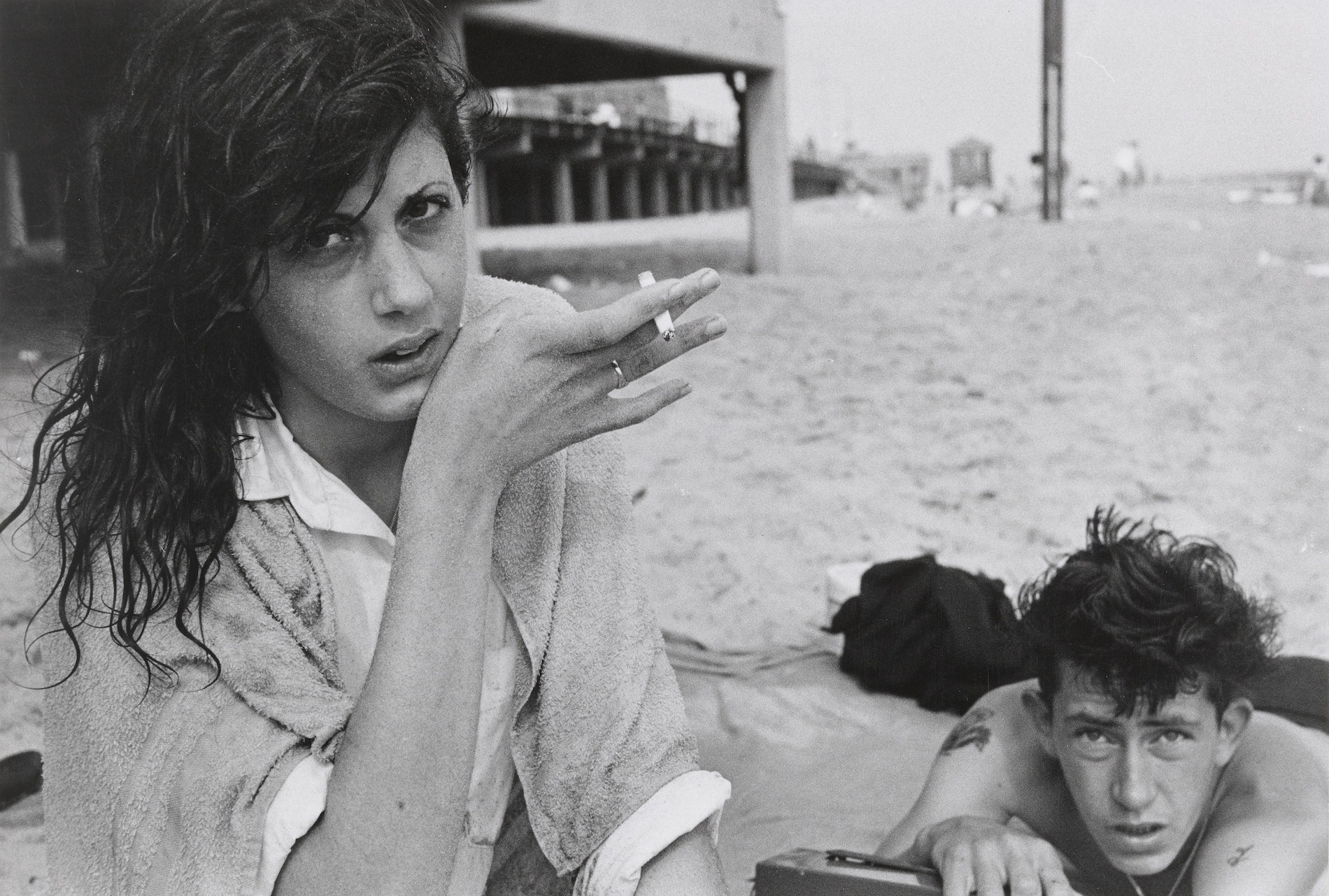

The Young Rebel in American Photography, 1950-1970 (1992): In the tail end of the 20th century, a nostalgia for all things rebellious 1950s bubbled up in popular culture (think Cry-Baby or the Stray Cats) and likely inspired the subject of this show. Tracing the influence of James Dean and Marlon Brando films — as well as Robert Frank’s seminal 1959 monograph The Americans — the exhibition explored the “adventurous photographers [who] abandoned photojournalism’s posture of objectivity” and how their “pursuit of young America’s struggle for self definition helped to create a new vocabulary for photography, which emphasized the subjectivity of personal experience.” The Young Rebel positioned four of these photographers at its center: Danny Lyon (who documented the Chicago Outlaw motorcycle crew), Bruce Davidson (who captured teen gangs on Coney Island), William Gedney (who shot hippie kids hanging around Haight-Ashbury), and Larry Clark (whose Tulsa series provided an unflinching, urgent portrait of drug culture).

Useful Household Objects Under $5.00 (1938): Considering the blockbuster exhibitions MoMA mounts each year, it’s funny to look back at one of the then-fledgling institution’s more economical shows. Consisting of over 100 household items (among them aluminum tea kettles, dish drainers, cigarette boxes, forks, spoons, shower curtains, lamps — even a trash can), the show aimed to demonstrate “it is possible to purchase everyday articles of excellent design at reasonable prices.” That same idea guided Humble Masterpieces, a show the museum opened nearly 60 years later in 2004, which featured Post Its, Bic pens, and Band-Aids.

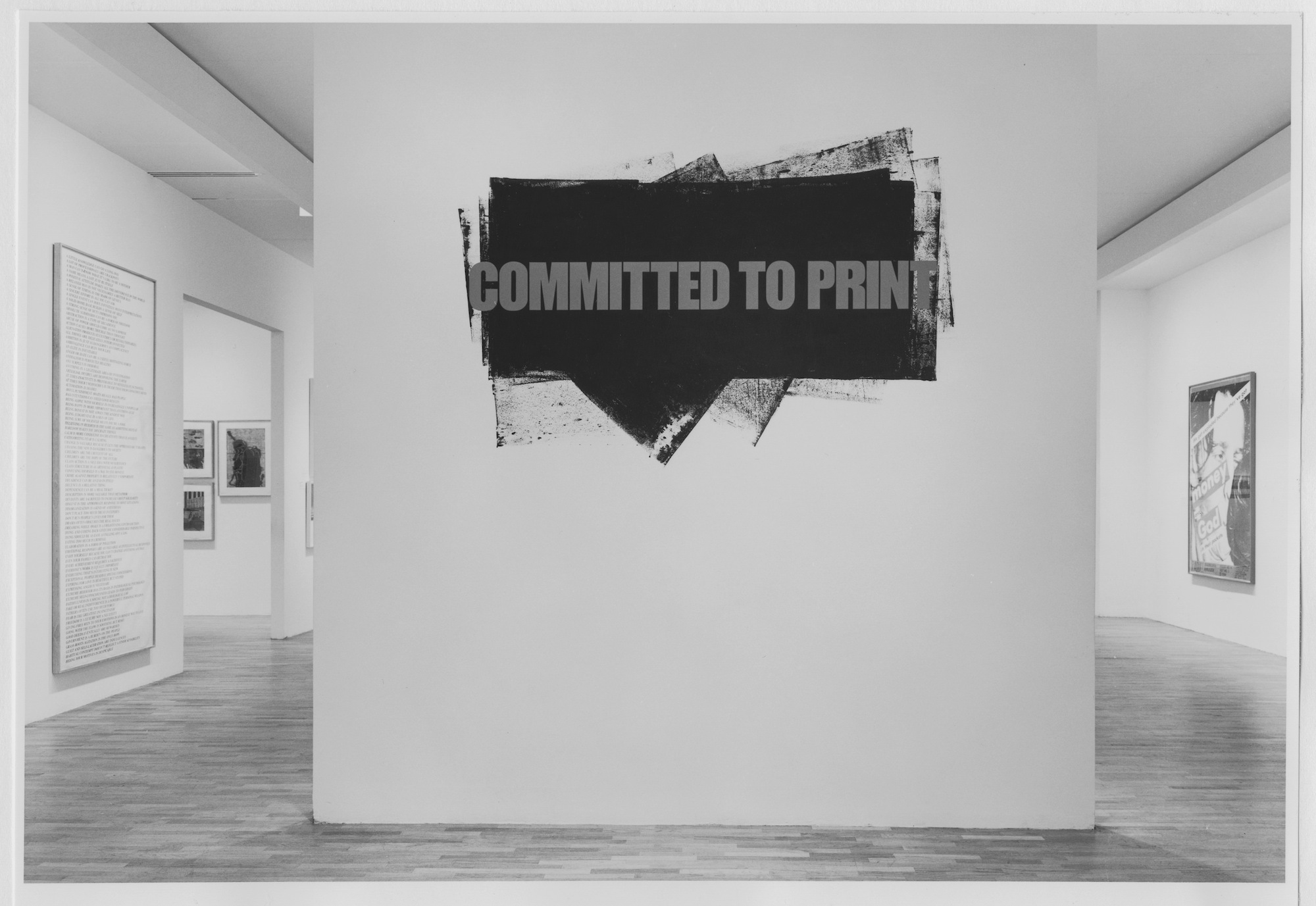

Committed to Print (1988): This late 80s show was the first museum exhibition dedicated exploring the social and political ideas communicated through printed American artworks — books and limited-edition posters created by artists who primarily work in painting or sculpture. Committed to Print was organized under a series of themes: governments and leaders, gender, nuclear power and ecology, war and revolution, race and culture, as well as economics, class struggle, and the American Dream. You’ll notice something is missing from that list, and from the exhibition’s full catalogue: any piece of art concerning LGBT rights or culture. By 1988, over 20,000 Americans had already died from AIDS-related causes; shortly after this exhibition opened, the death toll exploded, and continued to climb exponentially throughout the 90s. New York’s creative industries were particularly decimated by the epidemic, so the fact that AIDS is entirely absent from a show interfacing with global political and social themes seems more than a glaring omission. We’d like to time travel back and find out why.

The Pleasures and Terrors of Domestic Comfort (1991): This compelling photography survey also counted the “American Dream” as one of its guiding ideas; but unlike Committed to Print — which considered geopolitical themes out in a war-torn world — this show interfaced with social politics from inside the home. The Pleasures and Terrors of Domestic Comfort spanned over 150 pictures and 60 photographers, but much of the work it presented was made in the 1980s, by artists like Tina Barney, Doug DuBois, Carrie Mae Weems, Nan Goldin, Cindy Sherman, and Laurie Simmons. The exhibition’s color catalogue is scanned in full, and is really worth checking out; its introductory essay cites David Lynch and Diane Arbus.

Are Clothes Modern? (1944): In 2017, MoMA will mount Items: Is Fashion Modern?, a show collecting garments — from Levis 501s to LBDs — that have transformed culture over the past century. The question contained in the exhibition’s title revisits one MoMA posed over 70 years ago, in the only show it has ever mounted about clothing design. “The purpose of this exhibition is not to extricate the monstrosity of modern dress from the mass of confusing tradition, but rather to show its tremendous power in dominating and conditioning all phases of life,” architect and curator Bernard Rudofsky wrote in his exhibition statement.

The Last Works of Matisse: Large Cut Gouaches (1961): Even the quickest scan through MoMA’s exhibition archive reveals just how enamored the museum is with the French artist; Matisse’s name has appeared in nearly 40 exhibition titles (the number of shows his work has been included in is likely in the hundreds). MoMA has dedicated shows to his drawings, sculptures, paintings, and most recently, his celebrated cut-outs —the large-scale abstract paper works he created until his death in 1954. Just a few years after his passing, MoMA mounted 40 of the massive gouaches (or as he called them: “drawings with scissors”) Matisse made in the last four years of his life. I found a copy of the 1961 show’s unassuming exhibition catalogue in a used bookstore, and, perhaps stupidly, ripped out many of its pages to give to friends and hang on my walls. Fortunately for you and I, a full PDF scan of the book is available through the exhibition history here.

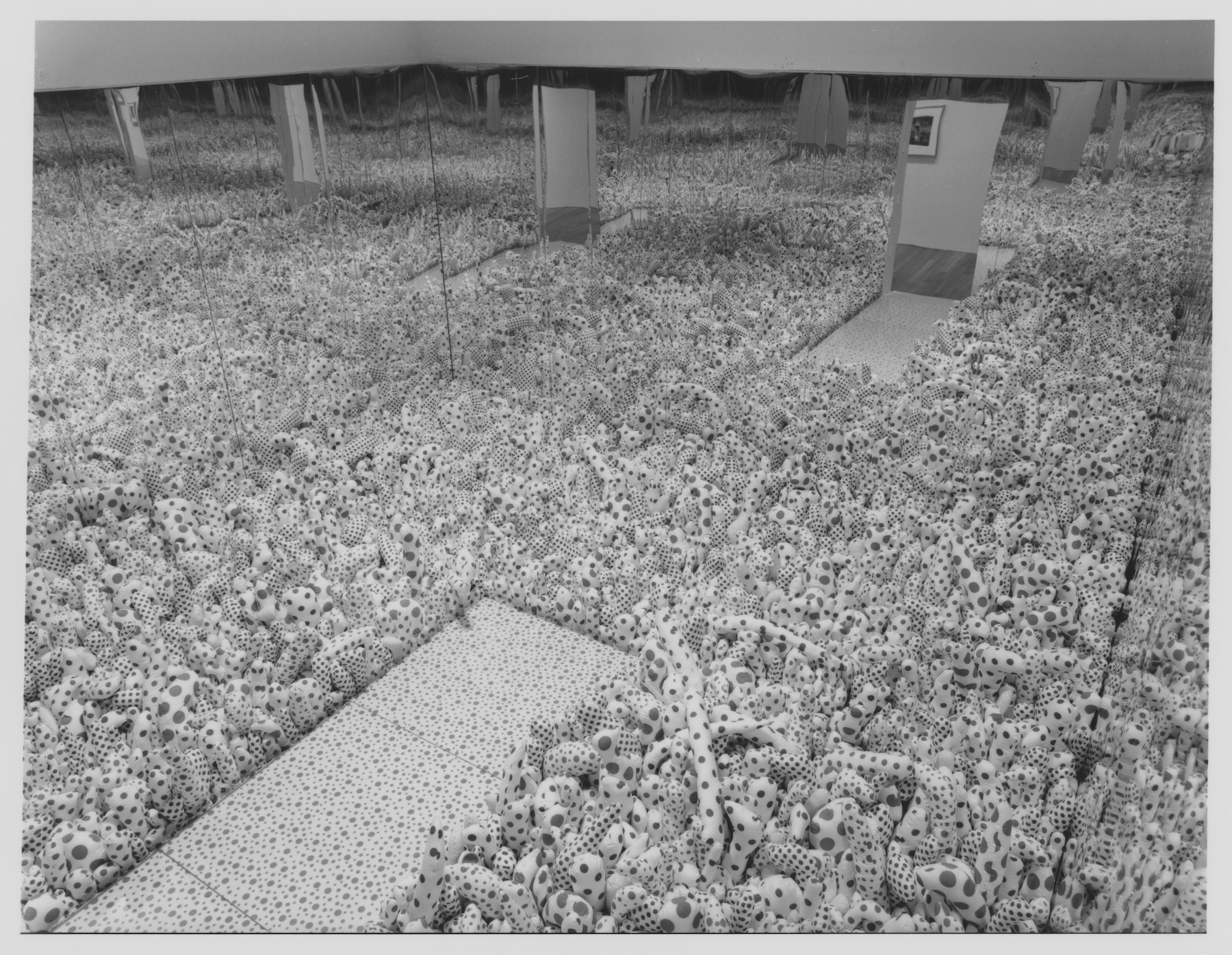

Love Forever: Yayoi Kusama 1958-1968 (1998): Many of us have stood inside Yayoi Kusama’s room of infinite lights, placed brightly colored stickers on her pristine white furniture, or taken a stroll through her garden full of mirrored spheres. But here’s one show you likely didn’t stand in an hours-long line for (I was seven years old, I had other things on my mind). This 1998 retrospective considered one of Kusama’s most fruitful decades, the period in which she first arrived to New York City. It collected drawings, paintings, sculptures, and installations Kusama created while in the US, much of it containing and endless sea of polka dots. The MoMA has uploaded a pretty trippy Japanese edition of the exhibition catalogue, which is really worth a look.

In Honor of Dr. Martin Luther King (1968): Just six months after Dr. Martin Luther King’s assassination in April 1968, the MoMA mounted an exhibition and sale of major American artworks — the first time a show was held to benefit another organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Interestingly, the MoMA exhibition archive contains two press releases for this show. One, dated October 5, states that 60 leading American artists have contributed works to the exhibition, and lists Mrs. John F. Kennedy as an Honorary Patron. A second, dated October 30, states that 81 leading artists have made contributions, and lists Mrs. Aristotle Onassis as an Honorary Patron. Alexander Calder, Mark Rothko, Jasper Johns, and Andy Warhol all exhibited work in memory of Dr. King; Ralph Ellison, James Baldwin, and Allen Ginsberg participated in a literary reading on the exhibition’s closing night.

Diane Arbus (1972): MoMA hosted Arbus’ first ever retrospective in 1972 — a moment in which interest in photography as an artistic medium was exploding, and just one year after the artist’s suicide. The retrospective spanned 125 photographs, including posthumous prints made from negatives Arbus did not finish processing before she took her own life. As fans might expect, the subjects of these documentary portraits ranged dramatically: nudists, children on the street, freakshow performers, Russian midgets, identical twins, Mexican dwarfs, ballroom dance champions.

Life of the City (2002): The events of 9/11 made a transformative impact on very many aspects of contemporary existence: one of them is art-making. This experimental show was presented in three distinct but connected elements: the first exhibited photographs that demonstrated the “richness, diversity, and power of the tradition of photography in New York, and which together evoke the vitality, grit, and beauty of the city.” The second called for photographic submissions from New Yorkers and museum visitors that captured their relationship to the city. The third, and perhaps the most poignant, involved a series of monitors that continuously displayed photographs taken on September 11, 2001, and during its direct aftermath. Despite its emotionally challenging focus, Life of the City celebrated a city for its tenacity, uniqueness, and love.

Explore the MoMA’s entire exhibition history here.

Credits

Text Emily Manning