Though American career politicians openly oppose socialist policy, the United States government has historically implemented it time and again to right the damage capitalism has wrought on the economy. During the Great Depression, the government created programs like the Works Progress Administration (WPA), putting more than 8.5 million people to work — including photographers such as Gordon Parks, Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, and Ben Shahn.

Their work documenting the plight of the nation helped shape public opinion, shorting up support for even greater reform through the New Deal, which brought housing, support and protections to millions of American homes and businesses. Socialist policy helped stabilise the economy, build infrastructure, and preserve the land, providing a firm foundation for post-war growth. But with the nation rising to become a global superpower, it was only a matter of time before corporate greed would cause yet another Wall Street crash.

By the early 1970s, the United States was experiencing “stagflation,” a downturn caused by the skyrocketing inflation and the longest stagnant economy since the Great Depression. As the OPEC oil embargo brought about a 45% drop in the Dow Jones, President Richard Nixon embraced socialism. In December 1973, he signed the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA) into federal law, enacting a nationwide service to train workers and provide them with jobs in public service.

“As a Republican, Nixon was trying to decentralise the federal government and give more power to the states,” says City Lore co-director Molly Garfinkel, curator of the new exhibition ART / WORK: How the Government-Funded CETA Program Put Artists to Work. “He saw CETA as a way to get money out of Washington DC and into the hands of local administrators and politicians.”

At the same time, Democrats were pushing for a public service component. They sought to continue the work of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society, which included the establishment of the National Endowment for the Arts in 1965. CETA, however, did not include a specific provision for artists to join the workforce. “It was the ingenuity of the arts community that found a way,” says co-curator Jodi Waynberg. “The first artist project was the brainchild of John Kreidler, who joined the San Francisco Art Commission after working for the Department of Labor Office of Management and Budget in Washington D.C.”

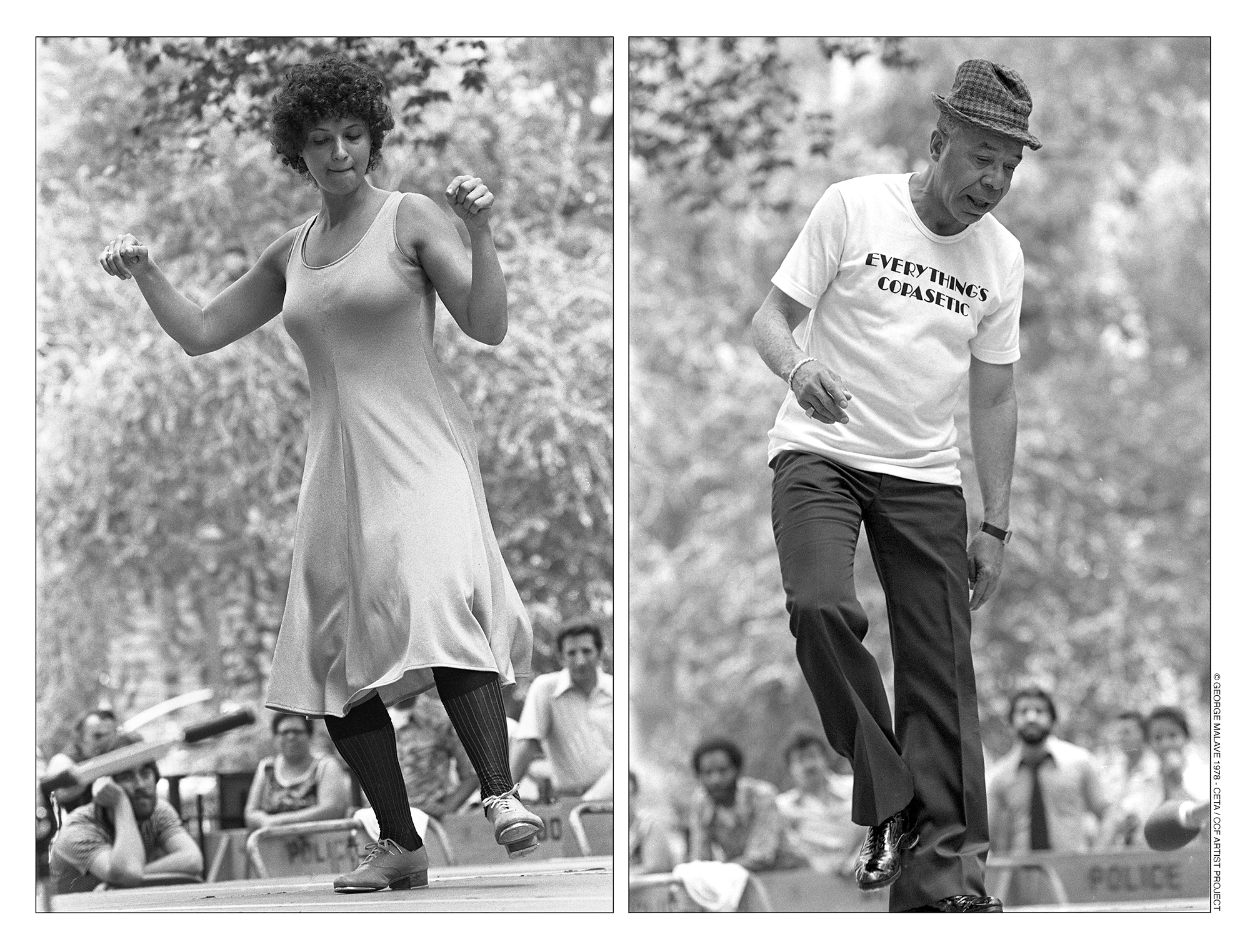

Once the seed had taken root, other cities quickly followed. Between 1974 and 1980, over 20,000 artists and arts support staff secured full-time employment through CETA – making it the largest federally funded arts project since the WPA. In New York City, the Cultural Council Foundation (CCF) launched the CETA Artists Project in 1978, with a budget of $4.5 million a year to fund the work of 300 artists, paying them $10,000 year plus benefits (nearly $46,000 today) to work directly with community organisations, on project teams, with performing companies, or on a wide array of public works.

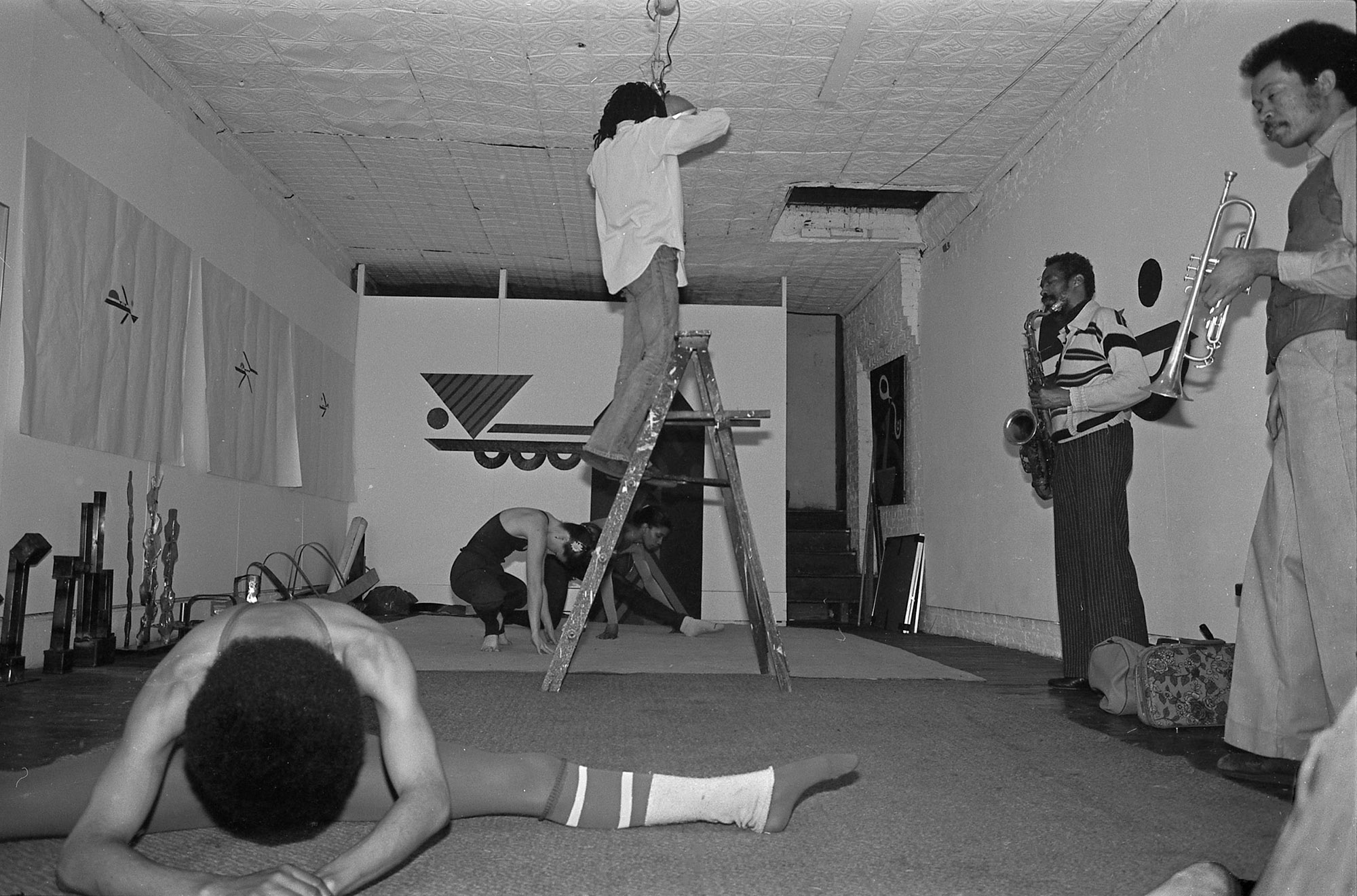

Photographers, painters, poets, dancers, and performers worked in prisons, schools, museums, libraries, and nursing homes; as well as on projects with prominent organisations subcontracted by CCF, including the Black Theater Alliance, the Association of Hispanic Arts, and the Association of American Dance Companies. An additional 200 artists found work through four other CETA-sponsored contractors, including Hospital Audiences, La Mama ETC, American Jewish Congress and Theater for the Forgotten.

“Although New York was on the brink of bankruptcy and all kinds of services were bring cut, participation with the arts was increasing,” says Jodi. “This was the beginning of thinking about the expansion of voices, representation, formats, and traditions in the arts. It opened up the field in many ways. It created an opportunity to artists who did not necessarily have the right connections in the art world to be given a meaningful chance to elevate their career.”

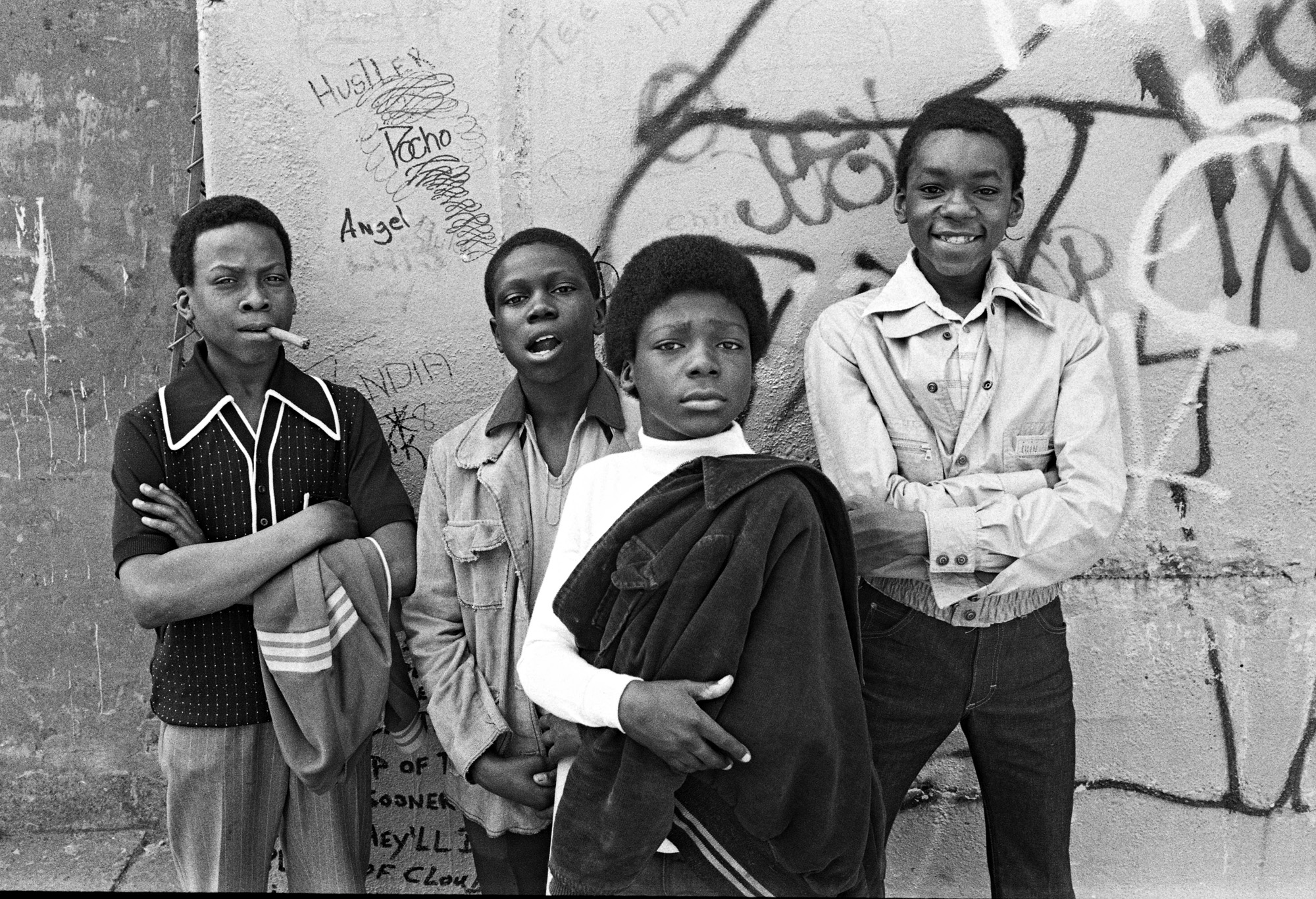

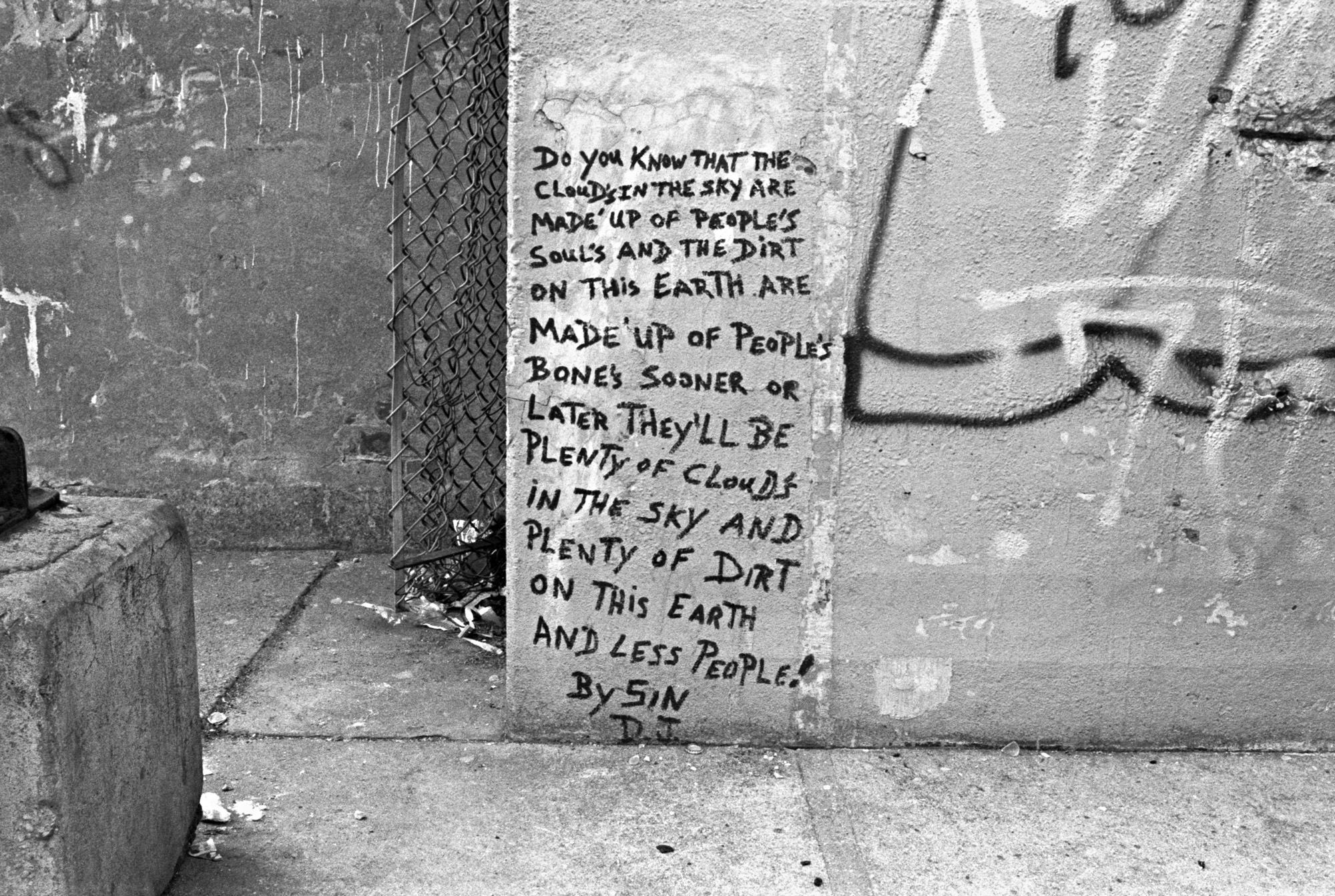

The CETA Artists Project nurtured the early careers of photographers such as Dawoud Bey, Meryl Meisler, Larry Racioppo, and Perla de Leon. With an eye towards infusing art and culture into the landscape of 1970s New York, CCF and the other contractors used photography to preserve local enclaves like the Jewish community on Manhattan’s Lower East Side and the Black and Puerto Rican communities of the South Bronx. The work made captured the DIY spirit of the times with other artist collectives like Colab, A.I.R. Gallery, and the 11th Street Photo Gallery reimagining the ways in which art could be made and shown.

“The CETA Artists Project happened against that backdrop of the alternative arts movement in New York,” Jodi says. “Artists empowered themselves to build infrastructure in a way that directly responded to their immediate needs, whether that was having a studio, health insurance, or sick leave. It was a shift away from the rarified space of the arts, and seeing the artist as a citizen within our broader communities.”

But with the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980, things would take a drastic turn. “Unfortunately, the political landscape shifted just as New York artist projects were getting stabilised,” Molly says. After seven years and 51 billion dollars invested in the American workforce, the Reagan administration began instituting massive cuts that resulted in the loss of thousands of jobs.

And with that, CETA virtually disappeared from the history books — its legacy awaiting rediscovery through the work of organisations like CityLore and Artists Alliance Inc. “Rather than focusing on well established artists and their work, the CCF cared about the artists as people and wanted to know their inspiration and motivations,” Molly says. “CCF had their own documentation unit made up of three photographers, three writers, and an archivist. They felt an obligation to preserve and document the projects because of how rare and unique it was.”

40 years later, the principles of the CETA Artists Project remain at the heart of conversations about what it means to live and work as an artist. Art is not the exclusive provenance of the elite, but an integrated part of our daily lives — by the people, for the people.

ART / WORK: How the Government-Funded CETA Program Put Artists to Work is on view at Artists Alliance Inc.’s Cuchifritos Gallery + Project Space through March 19 and City Lore Gallery through March 31, 2022, both in New York.