Los Angeles in the 90s is a mythic place. Police chief Daryl Gates — co-founder of D.A.R.E. — had turned the LAPD into a paramilitary force, only to leave in disgrace in 1992 after the LA Riots destroyed the city. Gangster rap became the voice of the people as gang violence sky-rocketed. Homicides reached new peaks during the first half of the decade, with gang-related killings accounting for 47% of those deaths in 1995. Feeding on the spectacle of violence, outsiders alternately fetishised or vilified it, but few got it right.

For Mexican-American photographer Gregory Bojorquez, his job during this period — in the newsroom of a San Gabriel Valley newspaper — was defined by prejudice against East LA’s Chicano communities. Gregory tells me about one particularly disturbing encounter with an editor who called him into his office and smugly asked if he was a gang member. Photojournalists at the paper would speak down to him for not having a degree, and editors would regularly send him on fluff assignments. So, although Greg loved photojournalism, he refused to tolerate disrespect, choosing eventually to leave the paper.

At this point, Greg had been taking pictures for some time. After graduating high school, he worked in a Los Angeles camera shop that covered his expenses: gas, beer, weed, and cigarettes. Like most teens and 20-somethings, what Greg wanted most was to be with his friends. So when he began photographing East LA, he did it simply as an extension of his life. “I was always hanging out, so people knew who I was,” he says. “Sometimes, that made it easier for me to take photos that were more spontaneous.” It wasn’t until Greg started taking film classes at LA City College that he realised he had a story to tell. The students were from Korea, Argentina, and all over the city — but not from East LA. They knew nothing of life in Boyle Heights, Lincoln Heights and El Sereno outside of what Hollywood showed them.

In the new book, Eastsiders (Little Big Man), Greg goes back to his roots and takes us inside his world, offering a multi-faceted portrait of family and community, love and loss. As a second-generation Angeleno, Greg shares a fascinating history of his family’s migration to East LA that underscores the inextricable link between the United States and Mexico. His grandparents arrived in Boyle Heights, a flourishing Chicano enclave, in the early 20th century.

Greg shares vivid stories passed down from generation to generation about the struggles and triumphs of his clan. His paternal grandfather was born on an Indian reservation in Arizona and never knew his parents. His maternal grandfather was born a twin in New Mexico; his parents kept his brother, sent him to work in a child labor camp, and never called him home again. He later went on to serve in the armed forces during World War II, landing at Normandy on D-Day and fighting in the Battle of the Bulge.

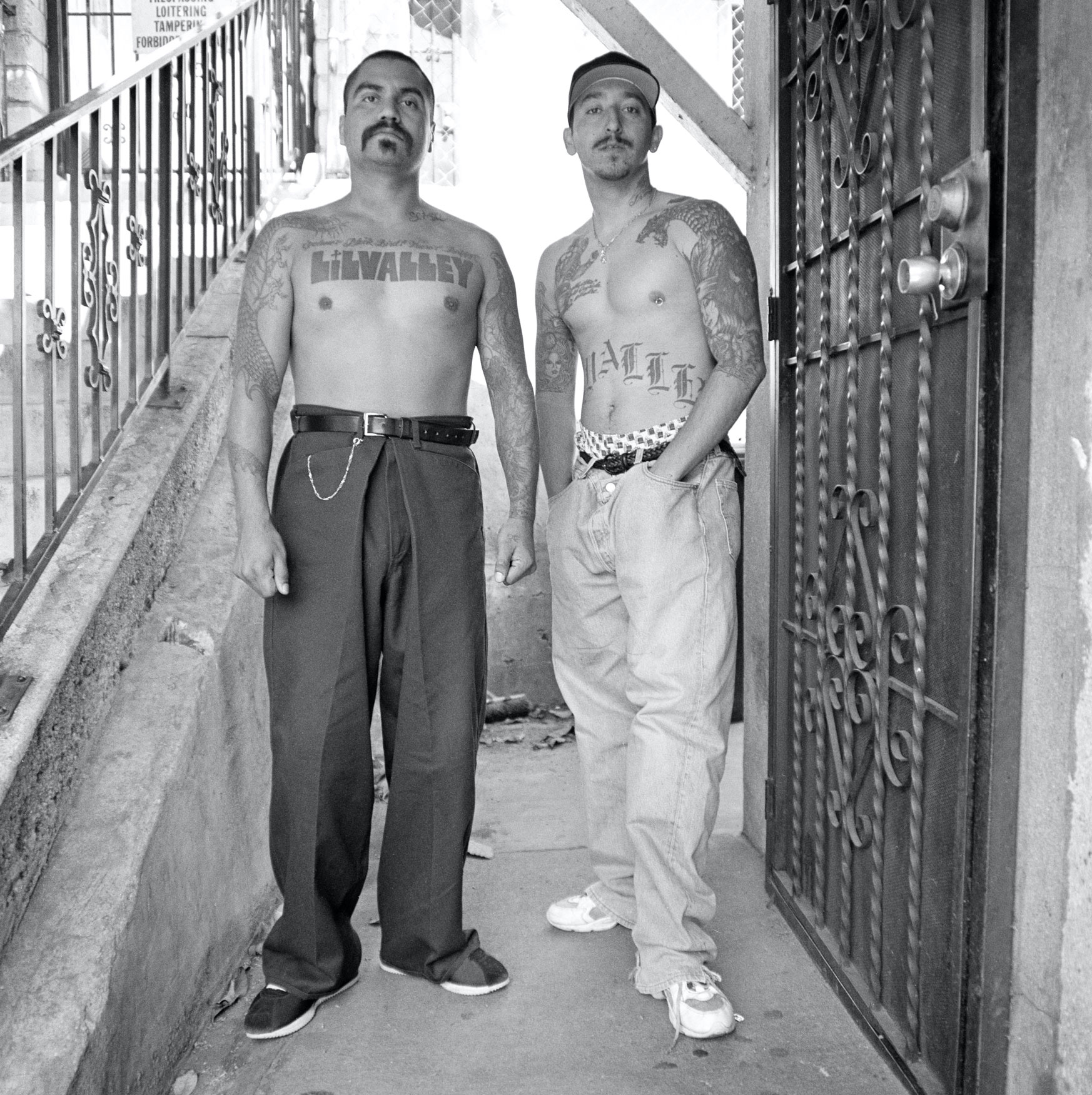

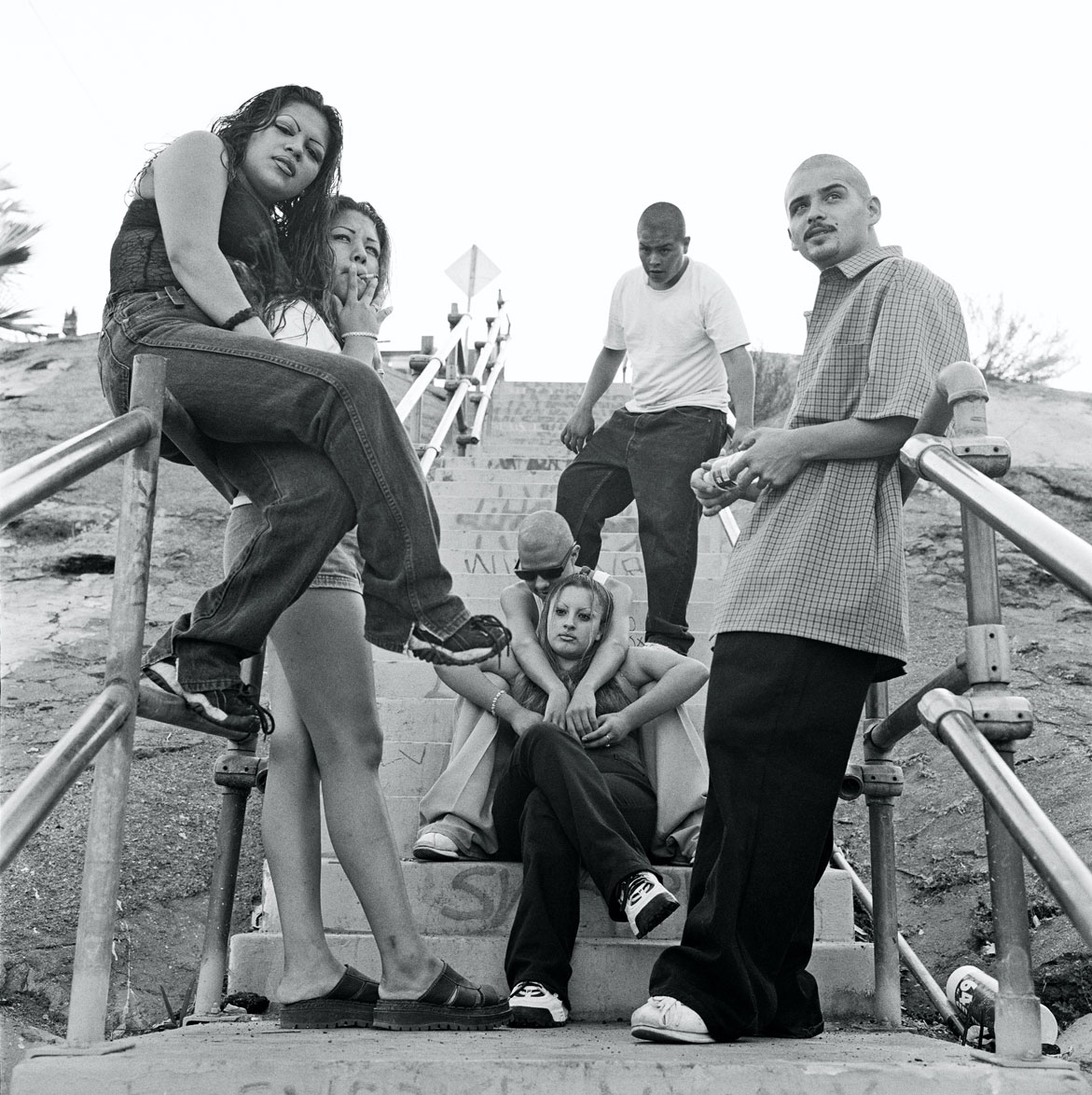

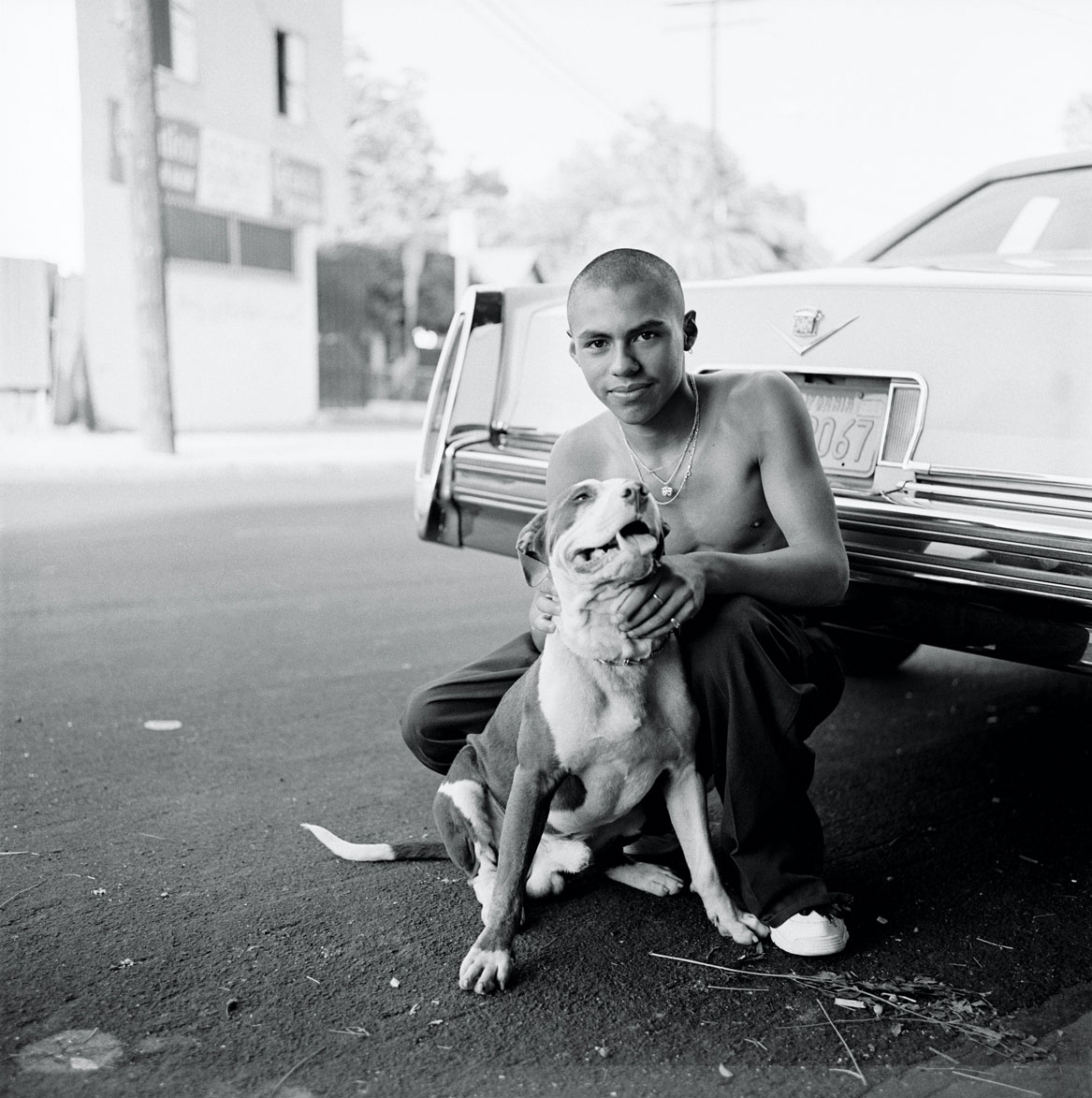

Both of Greg’s parents were born in East LA, which is home to more than a million people, nearly all Chicano. As an insider, Greg has a connection that outsiders lack, one that cannot be feigned or artificially created. “The people in Eastsiders are people I know,” he says. “I met the guy on the cover when I was 14. We’re 49 now, and he’s at my house all the time. We’re best friends. There are some people in the book that passed away. They died in different ways, and it affected me because these are people I grew up with. A lot of the work was done on Fifth Street. My friend Mike, who I grew up with, lived on that street, so it was the hang-out spot. The neighbourhood had a Bronx type of feeling. All the neighbours knew each other, and it was fun. Sometimes bad things happened. People would show up wanting to hurt someone, sometimes drive-bys, and that’s when things got serious. But the good overlapped with the bad.”

Greg points to a picture of a young man with a baseball cap in a car. “That’s my friend Bogart,” he says. “The photo opposite it is his family, and they’re standing at his grave. This is a guy I met when I was 14. He had a job selling suits at JC Penney, and later on in life, he got involved in other things. He was a gang member and was murdered.”

Because he knows them as individuals and not as stereotypes, Greg refused to photograph guns on principle. “I never tried to incriminate anyone in my book,” he says. “There are some photographers who know someone who can take them to the gangs, and the people are photo-ready. They’re dressed a certain way, showing their tattoos, and they have their guns out. People think, ‘That’s a great photo,’ but it’s a production. It’s set up. When guys are hanging out, the other guy doesn’t know you have a gun.”

But while outsiders could come into the community, get their shots, then pack up and leave, Greg could not. Although cops stopped him needlessly all the time, it was the gangs that made things hot. “My friends were telling me, ‘Man, you’re going to get shot. Everybody knows who you are. Everybody knows your car,'” he says. “Then a rival gang wrote gang graffiti all over my house, and 187, which means murder. I was starting to have a career, and I didn’t want to ruin it. I had to back off, which was really sad for me because I wanted to keep hanging out and taking these pictures.”

Although he didn’t set out with the intention to make a formal document of East LA, his commitment to the community proved it was possible to do just that simply by showing up and connecting directly with the people. For every photograph, there is a back story replete with intimate details that only friends could know. “It can be tough remembering things for good and bad,” Greg says, looking through his archive. “The photos preserve the memories and the emotions.”

Credits

Photography Gregory Bojorquez