When stylist Victoria Sekrier returned to her native Russia last spring for the first time in over a decade, she sensed a major cultural metamorphosis had taken place. At first, she saw glances of it on the job, in models’ off-duty wardrobes: ultra low-rise denim and bedazzled butterfly tops. Soon, she spotted the look in nightclubs, on her “For You” page and on the racks of Moscow super-boutique KM20. During the decade and a half that Victoria had been living abroad, bringing her eccentric-chic eye to Louis Vuitton and Eytys, a new youth movement began taking shape in the streets, on TikTok and on the proverbial runways of her home country. Out were the Vetements hoodies, Gosha Rubchinskiy graphic tees and adidas track pants of yore. In, was a new sexiness. The post-Soviet moment had passed and, from it, emerged something else entirely: the post-post-Soviet aesthetic.

The progenitors of fashion’s post-Soviet generation came of age in the midst of massive political upheaval in Russia. Their childhoods were coloured with memories of the communist regime and their teenage years, after its fall, were “uncertain, full of desperation and fear for the future,” Victoria says, relaying the experiences of her older brother, who grew up in the same cohort as Gosha, Demna Gvasalia and stylist and i-D senior fashion editor-at-large Lotta Volkova.

In bringing their uniquely post-Soviet perspective to the fore of global fashion in the mid-2010s, the trio drew upon their shared past, advancing a look inspired by the uniforms of their youths: bootleg graphic tees, hand-me-down-sized hoodies, patchworked-together jeans and army surplus staples. The look was distinctive and revolutionary on the world stage: a high fashion wardrobe inspired by Soviet constructivism as much as the Slavic working class. More than an aesthetic, it was a means of processing the precarity and disjointedness of the post-Soviet era; of reconciling the myth of the Soviet Union with its collapse. “Looking at the clothes from Vetements and Gosha, they’re always characterised as dark and emotionally heavy,” Victoria says.

Comparatively, the post-post-Soviet movement is characterised by a lightness or effervescence, looking just as much to pastoral simplicity and folkloric magic as the bubbly glamour of Y2K. The aforementioned butterfly top and low-slung jeans — the looks that first tipped Victoria off about this new aesthetic movement — were designed by Nikita Chekrygin as part of his label CH4RM’s SS22 collection. Just as Demna et al. drew from the cultural well of their 90s youth, the new generation is heavily inspired by the turn-of-the-millennium. It was an era defined by the rise of capitalism and, after the 90s saw the end of censorship in Russia, by the widespread influence of Western pop culture, too.

“All Western culture was coming from television, MTV and music videos,” Victoria says. “It was consumed, processed and expressed in this Russian way, which is brash, sexy, loud and unapologetic.” She points to Ukrainian girl group VIA Gra, who wear Dolce & Gabbana’s infamous SS03 “SEX” choker necklace in the clip for their 2004 single “Stop! Stop! Stop!”. It’s a definitive Y2K grail and undoubtedly an influence on Nikita’s creative output. In addition to low-slung denim, CH4RM’s SS22 collection features a twisted bralette look, complete with belly and upper arm chains.

While the new generation’s look and that of its predecessors are nearly night and day, the former owes its genesis to the groundwork laid by the post-Soviet cohort, whose global success was a game-changer for the country’s aspiring artists and designers. “We couldn’t believe that it could happen to Russian creatives,” Nikita explains. “The new generation started to be more open-minded. It made us realize that anything was possible and that it was important for us to bring our personal stories to the table.”

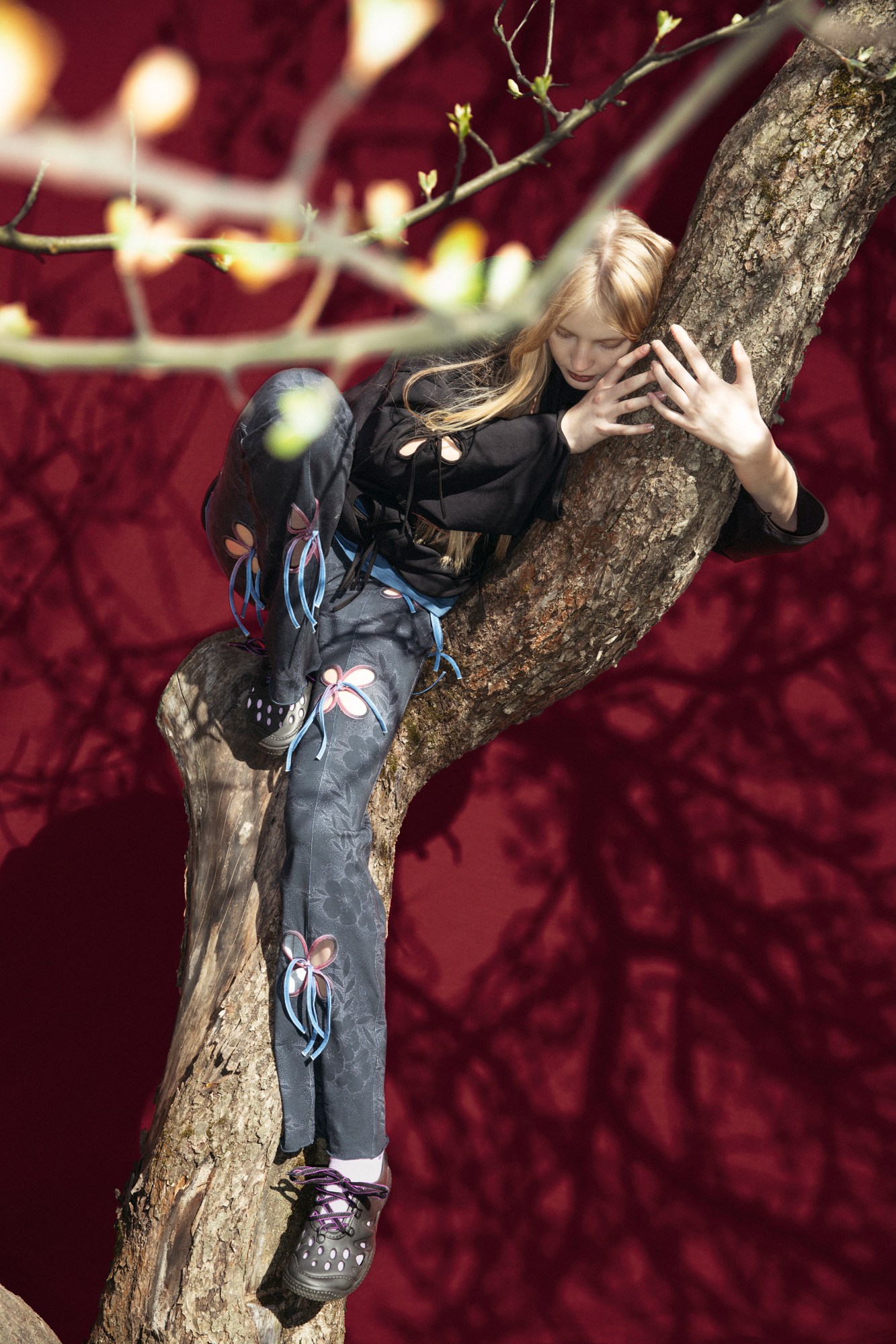

Consequently, the post-post-Soviet movement espouses an empowered sense of individualism, one that revels in its heritage. Designer Jenia Kim founded her namesake label, J.Kim, in Moscow a decade ago. Born in Tashkent to a Soviet-Korean family and raised in Russia, Jenia draws inspiration from the cultures of Uzbekistan and Korea, translating their national costumes and traditions into her own contemporary design language. For her SS22 collection, she looked homeward, once again. “After surviving quarantine and recovering from Covid with my family, I realized that they are my biggest strength,” she says. “I wanted to make a collection about my family and about our family celebrations, which I didn’t like and did not understand before. Now I appreciate these events because they bring our big family together.” Jenia’s grandmother even stars in the offering’s upcoming lookbook. Of the label’s playful look — the signature flower-shaped cut-outs that harken to Y2K’s sweeter side — the designer says, “Lately, people want to be different. It used to be the other way around.”

Founded by Numéro Russia alum, Masha Komarova, and Igor Andreev, emerging Moscow label Vereja draws its namesake from the tiny provincial town in which Igor was raised. It also takes its speciality — knitwear — from Igor’s childhood: his mother taught him how to knit at 11 years old. As Vereja, Masha and Igor bring together yarns of Russian folklore and rural tradition into impressive, artistically-rendered knits. Albeit, “in kind of a no-so-straightforward way,” Masha says. “Vereja is not just a brand, but a whole universe inhabited by all kinds of different creatures who travel from garments to art objects and back.”

Vereja’s past offerings have included crochet bras strung with mermaids (the Russian “rusalka”), majestic gowns that reminisce Snegurochka (folklore’s Snow Maiden) and homages to the Tree of Life. For SS22, the duo dug up more pastoral childhood memories of summer holidays in the countryside. “Wak[ing] up in a village house with the sun shining, pull[ing] on [our] shorts and [going] out to the garden right after breakfast […] sit[ting] among the potatoes, plucking weeds,” read the show notes. The collection, an ode to the cottage garden, was presented in a Moscow flower shop. Models walked down the makeshift runway holding children’s watering cans. Dresses were trimmed with lace, reminiscent of provincial curtains; the label’s signature knit work harkened to rustic tablecloths and blankets. This season, Vereja introduced jeans, patterned after those Igor’s grandmother worked on during the 80s, in his hometown’s denim factory. “We are into Russian heritage and Gen Z are into it too” Masha says. “They love the aesthetics of Russian provincial towns.”

While 00s pop culture colours Nikita’s work, his creative touchstone is and has always been his hometown of Tula. With CH4RM, the designer has channelled the unique energy of the village and its inhabitants into an aesthetic he calls “glamour from the provinces.” He elaborates: “Tula’s streets are full of people who are expressing themselves as if through costume rather than clothes. They possess a confidence that comes from within themselves.” The label’s signature low-rise denim is directly inspired by Tula residents who, Nikita says, have worn the outré style since its Y2K heyday. Along with photographer Marc Ashkame and Victoria, Nikita shot CH4RM’s SS22 lookbook in Tula, among parking lots, playgrounds and wide-open fields.

The label’s sexy style — all crop tops and micro miniskirts — is also indicative of a larger sexual revolution amongst Russia’s youth. “From my point of view, living in a country with third-world problems, it’s really difficult to differentiate what you create from what you feel. I see a desperate desire for freedom, to try and break out of the [country’s] constrictive standards,” says Moscow-based stylist Regina Ntahompagaze. “I see this trend towards extreme femininity in the fashion of my generation, and that’s exactly what I do. Everything I create is dedicated to undiluted femininity and sexuality. That notion of a ‘soft strength’ contrasts the militaristic and stagnant political situation of our country, which maybe is able to break out of such through the craft of artists and fashion creators.”

In the plethora of test shots on her Instagram, Regina and her model friends are wrapped in layers of strappy confections, swathed in ruffles, adorned with bows, bound in shibori and draped in unravelling knit separates. Also on the grid, photographs of London-based musician Yeule, styled by Regina in a hoop-skirted dress by Russian designer Sonia Trefilova. “Her work resonates entirely with my vision of oneself,” Regina says of the designer. “The fragility and femininity on the edge, nearing destruction.” Upon closer inspection, the chiffon of Yeule’s skirt is coming off its bones, as she performs it drags behind her, a train of decadent pink tatters.

Weaving together old and new, Anastasia and Maria Vaniushina of the label nastyamasha also map out these alternative expressions of femininity. For SS22, they played with the corset, opening up the notoriously restrictive style through crochet to advance what the sisters call an “easy-wear femininity, a fresh take.” Symbolically, it was a means of breaking with a larger notion of convention,” Nastya says.

“The new generation is a lot more open in terms of their sexuality and how they express it,” Victoria adds, speaking of her friends and collaborators, kids she’s met in clubs or seen out on the streets of Moscow. “They play with how much they can push the boundaries of acceptability, especially in Russia, which is still a conservative and religious country. And the misconception of Russian people, especially for women, that they are prostitutes or mail-order brides. It’s a very dated perspective, so that’s what I hope [this generation] can change, too.”

In addition to sex appeal, Nikita laces CH4RM’s designs with a heavy dose of play: digital love stories, cheeky text lines and teenage games. A pair of denim tripp pants from one of the label’s earlier collections is embroidered with the phrase, “Let’s keep it online only.” A miniskirt is emblazoned, “Not urs.” A men’s jacket, “I’m a flirt.” Each line is delivered with a proverbial emoji wink. “I use a lot of humour because I don’t know how you can live in Russia without it,” Nikita says. In addition to some much needed levity, these text message embroideries serve as playful nods to the internet, a crucial platform for self-expression that serves as a line of communication between Russian youth and the rest of the world.

“Before Russia was in a bubble, but now we have no borders,” Nikita says. For the designer and his peers, social media serves as a wellspring of positivity, a source of optimism as boundless as their own imaginations. Nikita says, with a smile: “TikTok spreads a lot of empowering messages like, ‘Everything is in your hands. Everything is possible.’” For a new generation of Russian creatives, it sure is.

Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more fashion features.