There are grounds for (cautious) optimism for 2018 being better than 2016 and 17: The predicted wave of far-right nationalism poised to sweep Europe did not triumph, although it did make disturbing advances. Recent electoral victories in the USA suggest a new wave of progressive politicians, including many women and people of colour (and in one case, a transgender thrash metal vocalist), might just put the brakes on the right-wing agenda. And in the UK, a weak government (propped up by the hardline DUP) and a newly emboldened left, along with a freshly energised youth culture, suggest there is everything to play for in coming years.

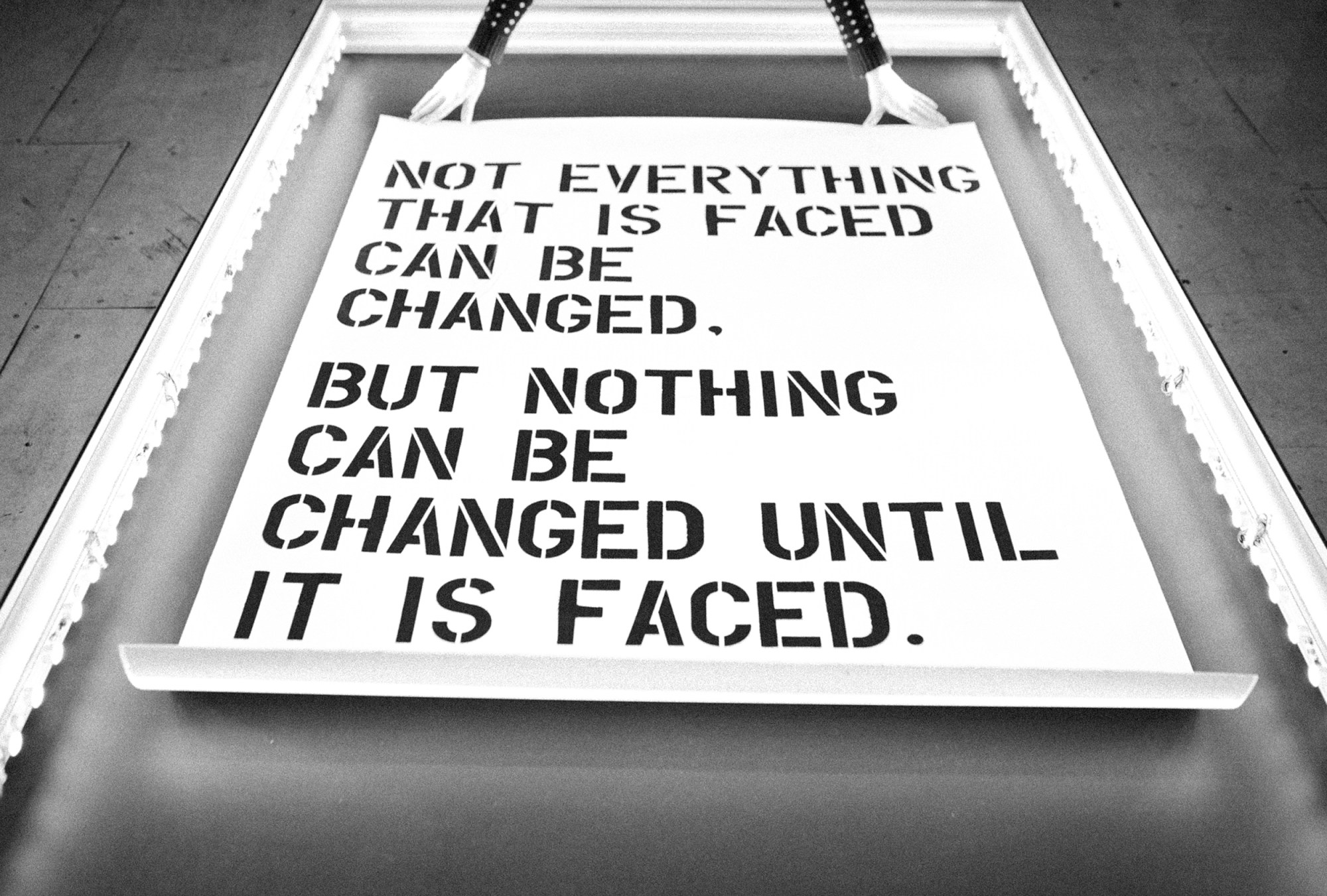

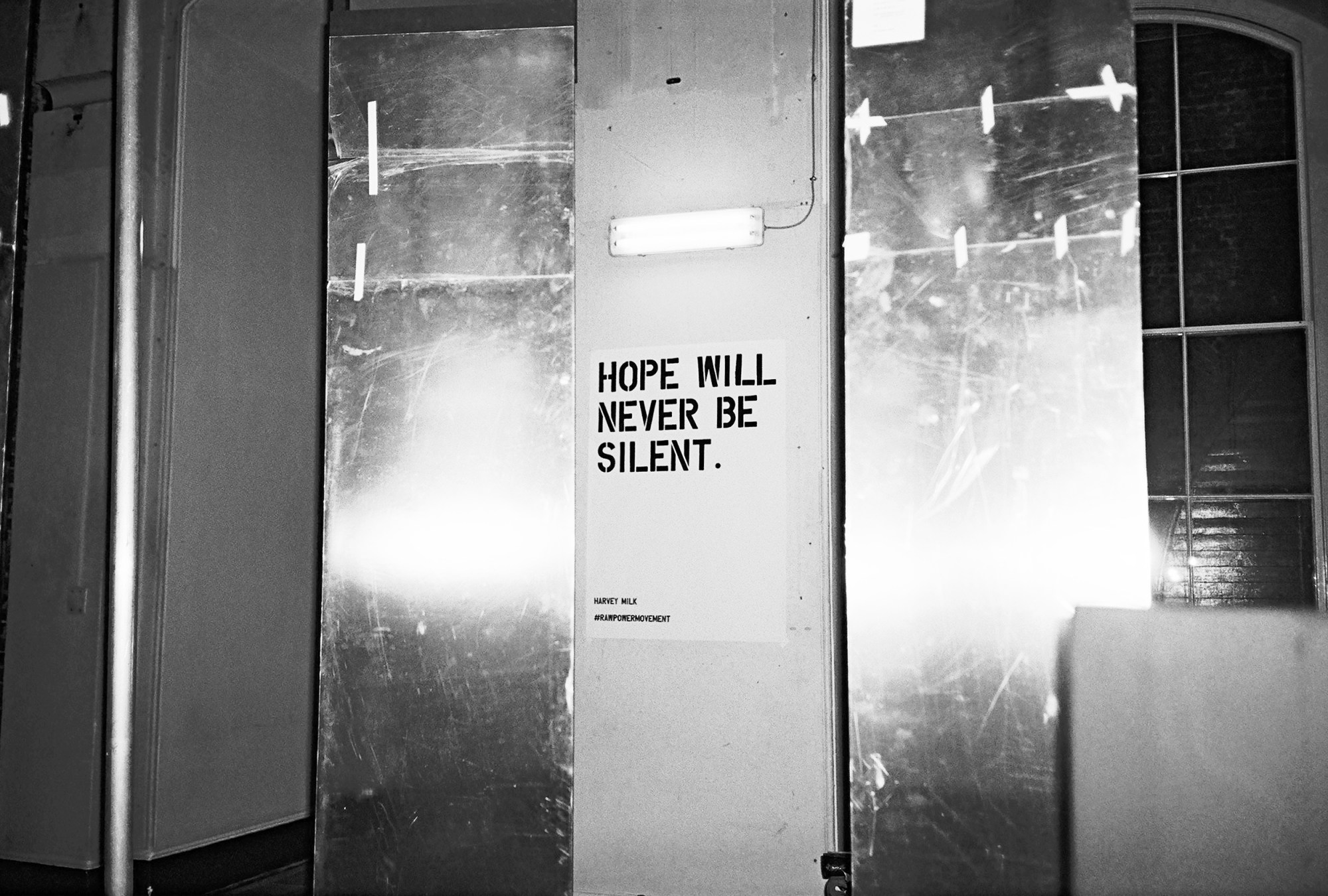

So, how to make the most of this wave of energy and optimism? If the anger and positivity of popular movement is not built on, it can fall away as quickly as it crests, as anyone who was part of the anti-war actions of the early 00s will dolefully remind you. One newly launched organisation, Raw Power Movement, is setting out to do just that, by challenging the creative industries to do more to enable people who are angry and motivated but might be put off by established activist organisations, and connect them via a programme of skill-swaps, workshops, exhibitions, digital media and IRL events.

“The time to hide is over,” says Carson McColl, long-time partner and collaborator of Gareth Pugh, who along with co-founders Heta Dobrowolski and Nusrat Faizullah, recently launched RPM with an event at London’s Somerset House. “Something is happening. I would often have this conversation with Heta about how, for a long time, we were waiting for people to come and rescue us. And then suddenly you have this realization no one’s coming to rescue you. You have to rescue yourself.”

So, break it down for us – who and what are Raw Power Movement?

The core crew is myself, Nusrat and Heta — we three are co-founders and working full tilt. Outside of that, we have a handful of amazing non-profits, charities and friends from the social sector. Then of course, there’s a growing band of creatives backing us up — our ‘anti-fascist all stars’ — including Gareth, Gaika, Ruth Hogben and Michèle Lamy.

Is it going to be a website or mainly social media? IRL events? What?

To give you the short version — we’re going to have events every couple of weeks, some major, such as takeovers and exhibitions, some more low-key, such as hacks and creative workshops. Meanwhile, activities like our skill-swap programme will run in the background.

Now you’ve had a few days to reflect on the launch of Raw Power Movement at Somerset House, how do you feel about it?

I’m happy the audience we brought together was so diverse. I feel there’s a lot of people who were there that hadn’t met before, and that’s something to celebrate. It was roughly 50/50 people from the social sector and from the creative world. The atmosphere was pretty electric, which I guess was the point.

So, your aim is to bring people from different aspects of creative culture, fashion, art and music, together with existing activist organisations? Do you want people to come together not just to talk, but take action?

Exactly. Raw Power was created to support people who want to be more politically active, but don’t know where to start. Initially, that involves presenting information in a way that is engaging. So often with political activism, it can be really dry and intimidating. When we first started out, we weren’t always made to feel welcome, or valued. That needs to change. So first, this is about creating a safe space where people can come and get information, zero bullshit. Secondly, it’s about trust, continuity and building relationships. We have all felt alone and overwhelmed by negativity at certain points, so it’s important to know someone has your back. Third, it’s about supporting people to find their own personal call to action in their day-to-day lives. The name Raw Power is based on the idea that everyone possesses the raw materials to contribute to a positive resistance.

You said that when you were first getting involved in activism, you didn’t feel particularly welcome. Why was that?

Like a lot of people, after the Brexit referendum and in the run-up to the US election, I started to get this feeling the time to hide was over. That something was happening. So, a few of us started trying to find things that were going on — activist meetings, talks, direct actions — that kind of thing. But it wasn’t easy. It was hard to break into, and in some ways that is for obvious reasons. There are many organisations that are right to be suspicious. But we couldn’t really find a first port of call.

If you didn’t feel certain groups were as open as they could be, did you address that directly with them?

That’s basically how Raw Power started — we would go to meetings, and there would often be a lot of talk but little action. Meanwhile, we could sense a wave of anxiety and anger rippling through wider culture, but no one seemed to be harnessing that, or working with an eye toward a mass movement. So in the end, we decided we had to do something ourselves. Which is NOT to say no other people are working towards the same goal — but it’s about joining the dots. For me personally, it’s about putting this fight in the lap of the creative industries. I feel a lot of creative people have abdicated their responsibilities — people who consider themselves ‘custodians of culture’ but don’t consider the fight for social justice part of their remit. That is no longer acceptable. We won’t accept this.

So, are you setting out to radicalise the creative industries?

Basically, yes. The reason it took so long for us to get this going is because even though we knew what we wanted to do, we had to go through a process and build a programme. Nusrat comes from the social sector and really understands how to build something like this, so we spent this summer working on a Theory of Change. From that process, we knew where to begin. We knew that 1) it was about getting informed 2) about building relationships, and 3) about supporting people in their own calls to action. So, it’s not just about Raw Power. That’s why we’re working with funders — when people come to us, if they want to start their own thing, we need to support them to do that. That’s the whole point.

What do you think about creative media at the moment, in this regard?

I was in the States when Trump was elected — somehow, I felt like I had to be there and I had dragged Gareth with me. After the result, Gareth flew home, but I stayed on for a bit longer and got a bus from New York to Woodstock. I guess I felt like the last time America had faced such an evaporation of hope was the failure of 60s counterculture.… But there’s now a level of sophistication in the way we communicate today — through digital media — that offers a really muscular and robust opportunity for counterattack. And the system is fragile. We often forget that.

Why do you think the creative industries abdicated their responsibilities in the way you’re saying?

It’s rooted in a desire for money, fame and notoriety. If you look at Donald Trump, he’s really just brought the worst parts of pop culture into politics. The Kardashians, Real Housewives, Donald Trump… Same shit, different outfit… This is an expression of where things have gone wrong, and it’s all tied up in pop culture.I was talking about this with the musician Gaika — who has emerged as a really loyal and formidable ally — before the launch. He’s a relatively mainstream artist, yet his work doesn’t shy away from talking about subjects like white supremacy or colonialism or systems of oppression. And in a world where his peers are primarily concerned with getting rich and famous, he’s found a major audience. It shows there’s an appetite for change.

You and your co-conspirators are already operating from within the heart of London’s creative community. How have you found the experience of trying to push these things as an insider?

What’s really interesting is that last year, before Trump’s election, we tried to talk to people about all of this, but nothing happened. There were a lot of rejection emails. After his election, I was less polite — it was more a sense of: you actually have a responsibility to do something. And it’s not about your brand alignment. It’s not about your media partnerships. Who gives a fuck? It’s about how everyone has to be involved in this conversation, and if you’re not involved in that conversation, then you’re destined to be ruled by people like Trump forever.

But you know how people say there’s always a moment when things change? And a whole generation turns a corner? It’s happening now. Brexit was the opening act, but I think Trump really shocked people. So, that second email got a lot of replies — and none of them were rejections.

OK, before we have to go, talk to me a little bit about the future of Raw Power. What do the next six months look like?

The big things we have coming up include a New Year’s Eve event we’re working on with PDA… given that we couldn’t think of anywhere more inclusive or amazing to reclaim 2018. At heart, this is about challenging expectations. Whether that means a takeover of Somerset House, or a basement club in east London, or having a one-on-one on the street or on the floor of a major department store, it doesn’t matter. This is about contributing to a positive resistance.

Roderick Stanley is founder of Good Trouble, a DIY digital and print magazine at the intersection of arts and culture with politics and protest goodtroublemag.com. Photography Magdalena Siwicka of www.gasoline.pictures

@_gasoline @magdalenasiwicka