Like so many online trends, fancams are constantly morphing and, thus, their definition is difficult to pin down. Nonetheless you’ll have likely seen one, be it spotted while absent-mindedly death scrolling through Twitter in the heat of a Cultural Moment, or nestled in the replies of a particularly air-headed take. They’re often edited to look like a home video from the 80s — popular, too, is the TikTok bling filter — and cut together in celebration of everyone from film awards winners to pop icons. Doja Cat’s “Boss Bitch” is a frequent soundtrack, so as to illustrate the crux of the fancam: to loyally elevate the figures we know and stan, often with a knowing wink.

As a trend, the fancam isn’t exactly hot off the press. The more simplistic fancams that first emerged from K-pop fansites — performance videos shot by fans without all the glitzy garnish — have been around for a long time. But what we now think of as a “fancam” has concreted itself within the online lexicon over the last year, becoming as near-ubiquitous on Twitter as reaction images and gifs. With the ever-expanding popularity of the fancam has come, too, an expansion of its subjects, this year boasting perhaps the most fascinating evolution of them all: the political fancam.

The confluence of a protracted, nail-biting vote counting process and massive youth engagement provided ample conditions for an eruption of fancams in the midst of the US election. In retrospect, the most popular fancams of the period carve out some of the most significant moments and shifts: they’re dedicated to everything from the pivotal swing state of Georgia, to Joe Biden eating ice cream and CNN’s John King (or, as he’s more appropriately known, the Magic Wall Man). They’ve stuck around ever since — even being used to celebrate the arrival of coronavirus vaccines — but they did not arrive without precedent.

As a trend, the fancam isn’t exactly hot off the press. The more simplistic fancams that first emerged from K-pop fansites — performance videos shot by fans without all the glitzy garnish — have been around for a long time. But what we now think of as a “fancam” has concreted itself within the online lexicon over the last year, becoming as near-ubiquitous on Twitter as reaction images and gifs. With the ever-expanding popularity of the fancam has come, too, an expansion of its subjects, this year boasting perhaps the most fascinating evolution of them all: the political fancam.

The confluence of a protracted, nail-biting vote counting process and massive youth engagement provided ample conditions for an eruption of fancams in the midst of the US election. In retrospect, the most popular fancams of the period carve out some of the most significant moments and shifts: they’re dedicated to everything from the pivotal swing state of Georgia, to Joe Biden eating ice cream and CNN’s John King (or, as he’s more appropriately known, the Magic Wall Man). They’ve stuck around ever since — even being used to celebrate the arrival of coronavirus vaccines — but they did not arrive without precedent.

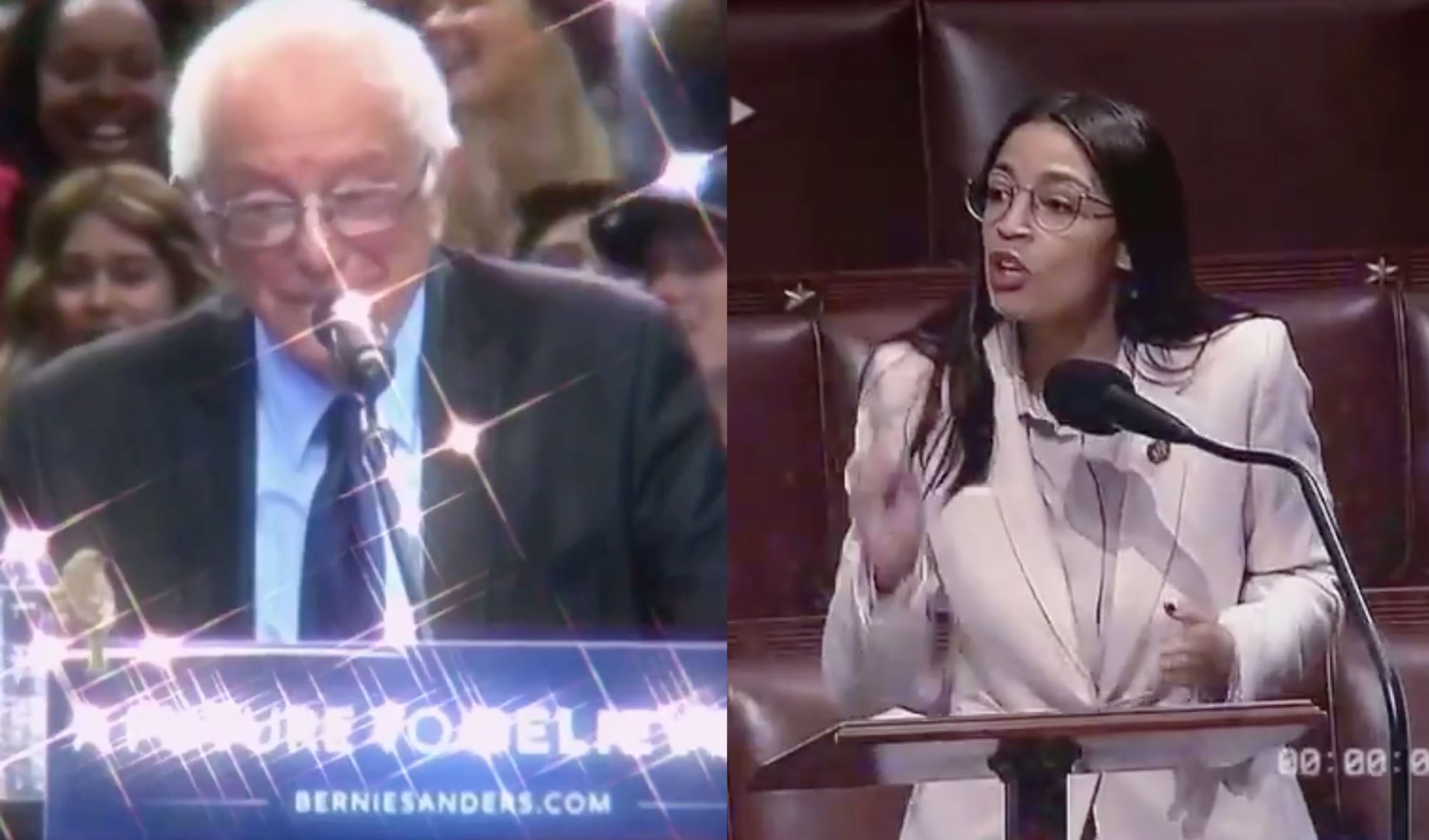

Like most of us, YouTuber and blogger Anjali finds electoral politics in the US exhausting. It was a week after Super Tuesday, when the greatest number of state primary elections are traditionally held, that she tweeted her tens-of-thousands of Twitter followers asking for Bernie fancams — given that the once-favourite for the Democratic nomination was now all but guaranteed to lose.

“I was having a bad day,” says Anjali. “My outlook after Super Tuesday wasn’t too good, so I wanted something lighthearted to watch that would make me feel a little hopeful that we could still, potentially, have a Sanders nomination.” The resultant thread is a veritable trove of treasures — from Bernie shooting hoops to Biggie’s “Big Poppa,” to a bedazzled mashup set to, yep, “Boss Bitch”. Bernie’s prune-like forehead glistening like a diamond, after all, is the content we deserve.

Can a short, effervescent video venerating a political figure actively change minds, or are they just a bit of air-headed fun? Louis, who runs Weirdo, an agency that helps brands reach underrepresented audiences on platforms like TikTok and YouTube, argues that there could be something powerful here. “The fancam is makeshift and zero-cost. Rather than recycle a cardboard box for a protest sign, people are recycling visual media. This is just a younger generation’s expression of fundamentally the same political energy, evolved for the digital commons.”

Even regular fancams have seen some functional use as a tool of direct action. For example, after the Dallas Police Department asked citizens to share “illegal activist protest” videos in the wake of the murder of George Floyd, K-pop stans inundated the department’s ‘iWatch Dallas’ app — which, of course, sounds totally normal — with K-pop fancams, effectively breaking it.

And not unlike direct action — albeit on a much, much smaller scale — the fancam has often been used to disrupt online discourse, similar to the way that K-pop stans wielded them against the Dallas Police Department. “Fancams are means of reclaiming digital space and interrupting trending conversation,” Louis adds. “Just post a video on any random post, to spread word of that thing you stan further. The way they’re being used can be an offensive, rather than defensive, tactic.”

The precarious economic and social conditions inherited by young people, Louis infers — amplified to the nth degree by Ms Rona — has influenced their methods of activism, both within the digital sphere and otherwise. “Gen Z are a generation who’ve had to embrace a DIY mindset. The need to be self-reliant and creative is a critical and socially-valuable skill. They’re deeply suspicious, too, of messaging, be it from brands or institutions, that seems in any way inauthentic. I would argue we see this in aesthetics, too.”

When we consider the thrown-together aesthetics one might traditionally assign to grassroots youth activism — makeshift cardboard signs with less-than-flattering puns, for example — the fancam is not such a surprising evolution of online political engagement. This is a sphere, after all, that has long been dominated by memes and reaction videos. This also plays into the attractive formal juxtapositions of the fancam: between the low and the ostensibly high-brow, or the gaudy and the refined.

That said, there is a profound difference between the digital deification of pop divas and politicians. “I’m not for idealising politicians in general — idolising folks in the bizarre US electoral system isn’t quite aligned with my politics,” Anjali stresses. She makes a great point: fancams may not have the power to meaningfully shift mainstream opinion, but there is a quiet threat posed by political figures accruing something akin to standom, as opposed to being objectively held to account.

On the other hand, political fancams could just be a poppy, slightly obnoxious trend. “The finished product [of a fancam] is a little removed from reality, so I think for me there’s a funny juxtaposition,” she adds, and indeed, that could be all that there is to it: inside jokes shared among like-minded young people interested in politics, as opposed to a method of online canvassing.

The fancam isn’t entirely specific to US electoral politics. Joe, a recent Law graduate, started the @ukpoliticsfancam handle on TikTok back in June. The page boasts an expansive portfolio of fancams dedicated to British political figureheads new and old. Novel, too, is its bipartisanship, equally celebrating the likes of Jeremy Corbyn, Andrea Leadsom and Boris Johnson. (Comments under the latter’s fancam read: “Boris is a barb,” and “should’ve stayed in the drafts, sis”.)

“I follow quite a lot of young politicos,” Joe writes, “and there’s always an abundance of memes and jokes for just about every event and story in politics. To make a fancam for a politician I liked felt not too strange an extension of the memes that already exist.” Like Anjali, Joe appreciates the funny juxtapositions his fancams offer above anything else. “I’m not a particular stan of anyone myself, but I find stan culture quite funny, so hoped other people would appreciate the funny side in a Thatcher fancam.”

The coronavirus crisis, he thinks, has propelled otherwise lesser-known political figures to the forefront of the public consciousness. Think the explosive rise of “Dishy Rishy,” or that Matt Hancock is now, for better or worse, a household name in the UK. “I feel as though people who aren’t massively interested in politics have become more familiar through daily press briefings, coronavirus updates, and the like — so politicians have, in a way, taken on celebrity status even more so than usual.”

The political fancam is hardly going to change hearts and minds. If there was any real use here, you’d think that political figures — not least in the midst of the most profound election cycle in decades — would’ve co-opted them already, just as Obama became the first meme president. What is powerfully demonstrated, however, is the collective political engagement of Generation Z. Data suggests that Gen Z are more politically active than their Boomer and, sometimes, Millennial parents. The evolution of the fancam not only re-affirms the significance of the online sphere, but also the unique political ingenuity of digital natives.

But please, if you’re reading this and thinking of splicing sped-up clips of Rishi Sunak together against that bit in Nick Minaj’s “Roman Holiday”: don’t.