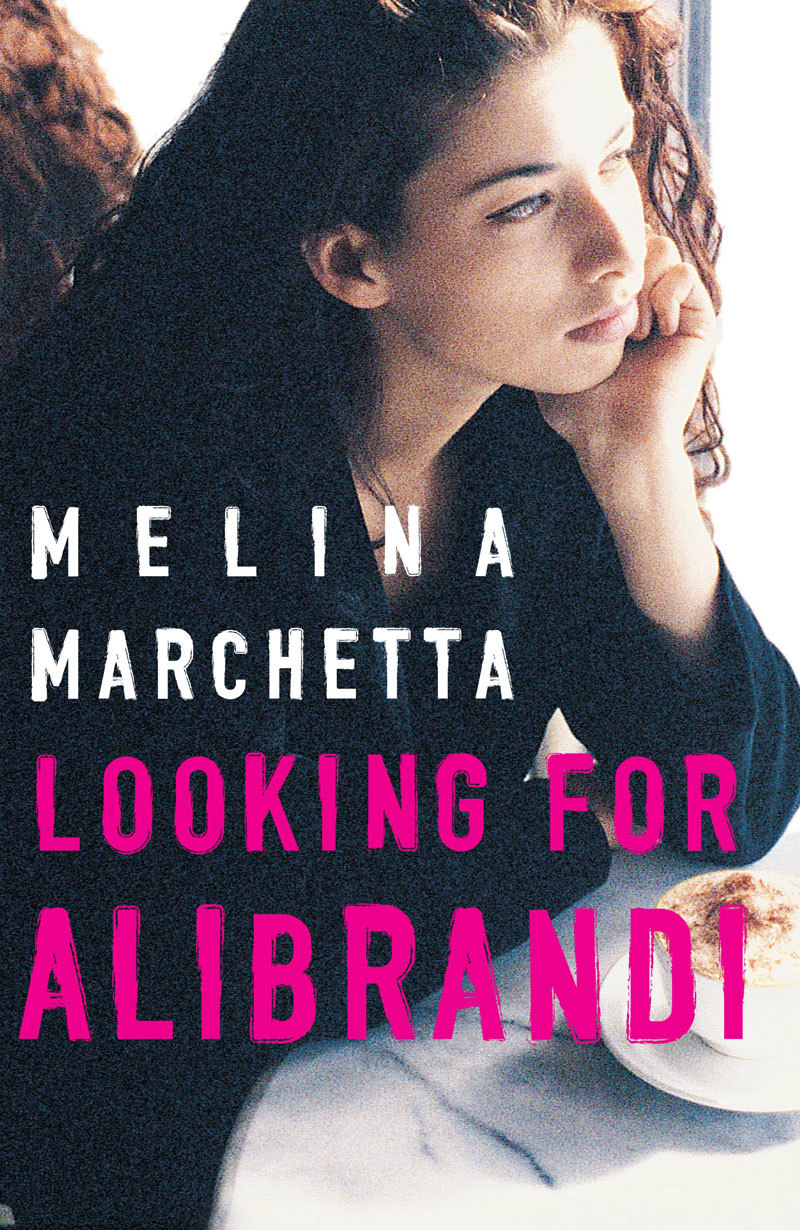

Despite all experiencing it, our ideas of adolescence are often modelled on what we see. The prevailing images of angst, drama, scripted and staged coming-of-age moments are borrowed constructs. So when something real breaks through the public consciousness it stands out. 25 years ago, that happened with Looking For Alibrandi.

Everything about the book was unlikely: written by a very young woman who didn’t finish high school, it dealt with the experiences of a second generation Italian teenager. But despite the “fringe” aspect, it immediately took root in the Australian subconscious. Central character Josie was so vivid, she became a mirror that hasn’t tarnished over a quarter century. While the book was an amalgamation of the lives of author Melina Marchetta and the women around her, it’s become something of a literary rorschach test. Everyone can find themselves in Looking For Alibrandi, be it through proud but confused Josie, her sensitive mother, powerful grandmother, absent father or the boys she loves and who love her.

To celebrate the novel’s anniversary this year, we spoke to Melina Marchetta about what it means to create something a country can’t let go of.

You were pretty young when you wrote this book, barely in your mid 20s, how has your relationship with it changed over the past 25 years?

Quite extensively. It’s your first book so you’re always going to have a soft spot and strong feelings about it. You look back on it and I think, I’ve come along way as a writer in 25 years. Sometimes when I read an extract from it I think, my goodness.

Also, it was the only novel in my life for 11 years. To think about them like a child, my other novels had a few years on their own then there’s the next one. But for Alibrandi, there was 11 years between novels, I felt as if I got asked about it everyday of my life. You feel as if you’re defined by something that you created, at times that did feel quite suffocating. I felt as if I couldn’t go in another direction.

Do you still feel tethered to it?

Not as much as my second novel (Saving Francesca) because it was more of a personal story. Also with Francesa I actually knew what I was doing. With Alibrandi I almost couldn’t take credit for what people loved about it; that was a great thing, it meant it came from the heart and I wasn’t thinking too much about constructing it.

But I do, because everyone else does. You get caught up in how other people feel about that novel: 25 years on people almost have tears in their eyes if they find out I wrote that novel, it’s like they can’t control the emotion. That’s so touching, there’s no way I could be disdainful of it. I feel emotionally attached to it, but I’ve moved on more than others have.

That’s what’s so special about the book, people hold it so closely. Are you ever surprised by what others see in it?

I’m more surprised by who is affected by it. I used to pick people’s brains, to use labels, if a young Anglo girl really had an attachment to it I’d ask why. In the early days I was speaking at a festival and an old man came up to me and said how much it meant to him. I just thought wow, where are you coming from in regards to this story? He was coming from the part of Josephine’s grandmother, the man she had loved in Queensland. He told a story about being in love with a woman he couldn’t marry for family reasons.

So many people first connected to this book at school; it really captures that feeling of being around so many people “like you” but being so out of place. I was surprised to read you left school early and didn’t personally have those experiences in the book.

I left school at the end of year 10, so it wasn’t based on my experience at all. But my sisters and friends, we went to a 7 to 10 school, so if you went on to year 11 and 12 you had to go onto another school. I remember how hard it was for them because they were in this new environment and certainly didn’t feel like they belonged. I’m a good observer, when it came to writing this I knew she had to be a fish out of water. I kind of stole that emotion from people close to me.

So many ideas about adolescence in Australia are absorbed from overseas. Looking for Alibrandi is often put forward as the totem of what it means to be an Australian high school kid. How did you present a feeling so evocatively when you haven’t had it yourself?

Only part is not my experience, the part about her going to that school. The other part of her is growing up in an Italian family, growing up in Sydney and being very aware of the divides, that was easy to write about.

Also, I was 17 years old and in the workplace. I wasn’t old enough to get into pubs where my workmates would go and I wasn’t hanging out with my friends from school so I felt really caught between things. It was easy to write about not feeling you have a space.

Often when we dissect young female characters they’re presented as either the personification of purity, or a meek, passive victim. But Josie is flawed and complex, I know she is partially based on you sister, but how did you go about constructing a “real girl” in fiction?

There was a part at the end of the process when I said to my publisher I wanted to change one of the parts where she’s awful to her mother. They said, “no you can’t because you don’t own it anymore.” They weren’t being mean, rather saying she now belongs to us because we’ve read her, we like her, and this is going to make her more real.

In creating her in the first place, the part I got from my sister is that she is very clever and outspoken with a strong sense of truth that gets her into trouble. I loved that part of her. I knew I had to do that with Josie — not make her that perfect She needed a few knock backs, because I don’t know anyone who hasn’t had knock backs. She’s a construct of me, my sister and the girls I grew up with who were smart, but also cool, but also uncool — all these different things.

It’s interesting how much we’ve circled back to these conversations around the worth and complexity of teenage girls in today’s media.

Definitely, but not just young women, women in general. What makes me sad is that while we’ve made progress, in 25 years it hasn’t really lept into something completely different. I still feel there are gender issues that haven’t been addressed and I think that’s something I’ll be looking at into my old age.

Something I hadn’t thought about is that we’re all so excited that this novel still resonates today. But it’s kind of sad that so many of the things Josie is frustrated about in her gender are still totally present 25 years later.

Maybe that’s why the book is still in print and people still read it, because a young girl can still relate to it. But I guess I’ll never know. It’s a lovely surprise to me that that character still somehow, someway still says something to young people.

Josie would be in her early 40s now, where do you think she is?

I always knew what would happen to her, there are no surprises for me. She would have ended up going into law, there is no way she’d change her mind about that. There is a bit of doubt at the end of the novel but she would have gone down that track.

I feel I did write about her when I wrote about Franchesca’s mother in Saving Franchesca. In that novel her mother has a breakdown, and that’s not to say Josie would have, but Mia was the type of dynamic character everyone was drawn to. She was a small person with a big personality, and pretty disappointed in her daughter for not speaking out. There are a lot of Josie traits that I gave to a 40 year old woman: ambition, maternal love, love for her family but wanting more for her daughter than her daughter believed she deserved. That’s the kind of mother she would be, she would not allow her child to settle for less. She would still be fighting the fight and stepping on toes, which I really love about her.

Catch Melina Marchetta at the National Writers’ Conference as part of the Emerging Writers’ Festival. Grab tickets and info here.

Revisit the 2000 film at the Festival’s movie night on 18 June.

Credits

Text Wendy Syfret

Screengrab via YouTube