Frieze, the annual art fair, is under way in Regent’s Park in London (October 3 to 6 ) for its latest edition. In the Spotlight section of Frieze Masters, which features work made before the year 2000, there are notable solo presentations highlighting the work of pioneering artists from around the world.

Three artists in this sector—all born within the same decade—especially caught our eye. Each one showed a feminist approach to their art long before modern media was lamenting the lack of female representation at the institutional level. Prescient and resonant today, the work is bold, colorful, confrontational about gender, and—perhaps best of all—wonderfully irreverent.

Sidsel Paaske

Holtermann Fine Art, London

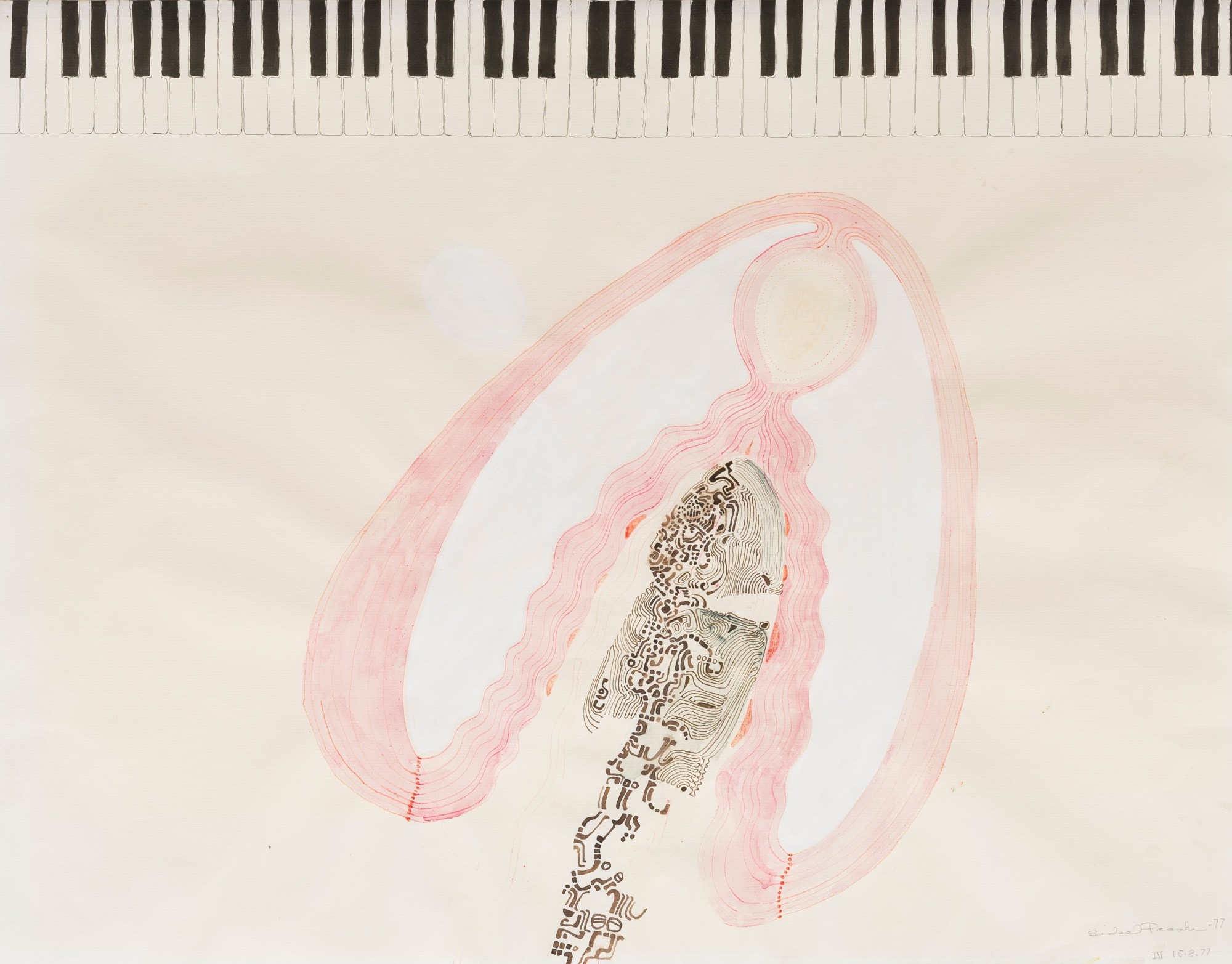

Norwegian artist Sidsel Paaske produced works on paper during the 1960s and 1970s, most notably a series entitled “Vaginale Ikonografier” (“Vaginal Iconographies”). The forms, positioned on spare white, unleash something primal in the sylphlike lines and speckled gestural bursts, articulated in pencil, felt-tip pen, India ink, and watercolor. They emit a sense of revelry, and communicate a relief of no longer holding back. And Passke certainly was held back: she was expelled after one semester at the National College of Art and Design in Oslo for becoming pregnant (she gave birth to a son in 1957). Thereafter, she countered establishment norms with explicitly clitoral forms and phallic silhouettes, doubly rejecting the blatantly sexist art academy and expressing celebratory wonder of the female form. She looked outside the realms of art as well. In the early 60s, she studied at a women’s vocational college in Oslo and qualified to become an art teacher; she later worked at a psychiatric care center and a prison. Having collaborated with musicians, notably the trumpeter Don Cherry, she laced the syncopated influence of jazz into her work, and organized a Women and Art exhibition at Kunstnernes Hus in Oslo during the United Nations’ International Women’s Year in 1975. She died young, of a brain tumor in her 40s, and her work was omitted from the art history narrative—barring a 2016 retrospective at the Nasjonalmuseet in Oslo (“Sidsel Paaske (1937-1980) On the Verge”), which also featured the scope of her output from textiles to jewelry. Her work has otherwise not been shown outside Scandinavia since the mid-70s. It’s a pleasure to discover her animated yet graceful aesthetic.

Jacqueline de Jong

Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, London

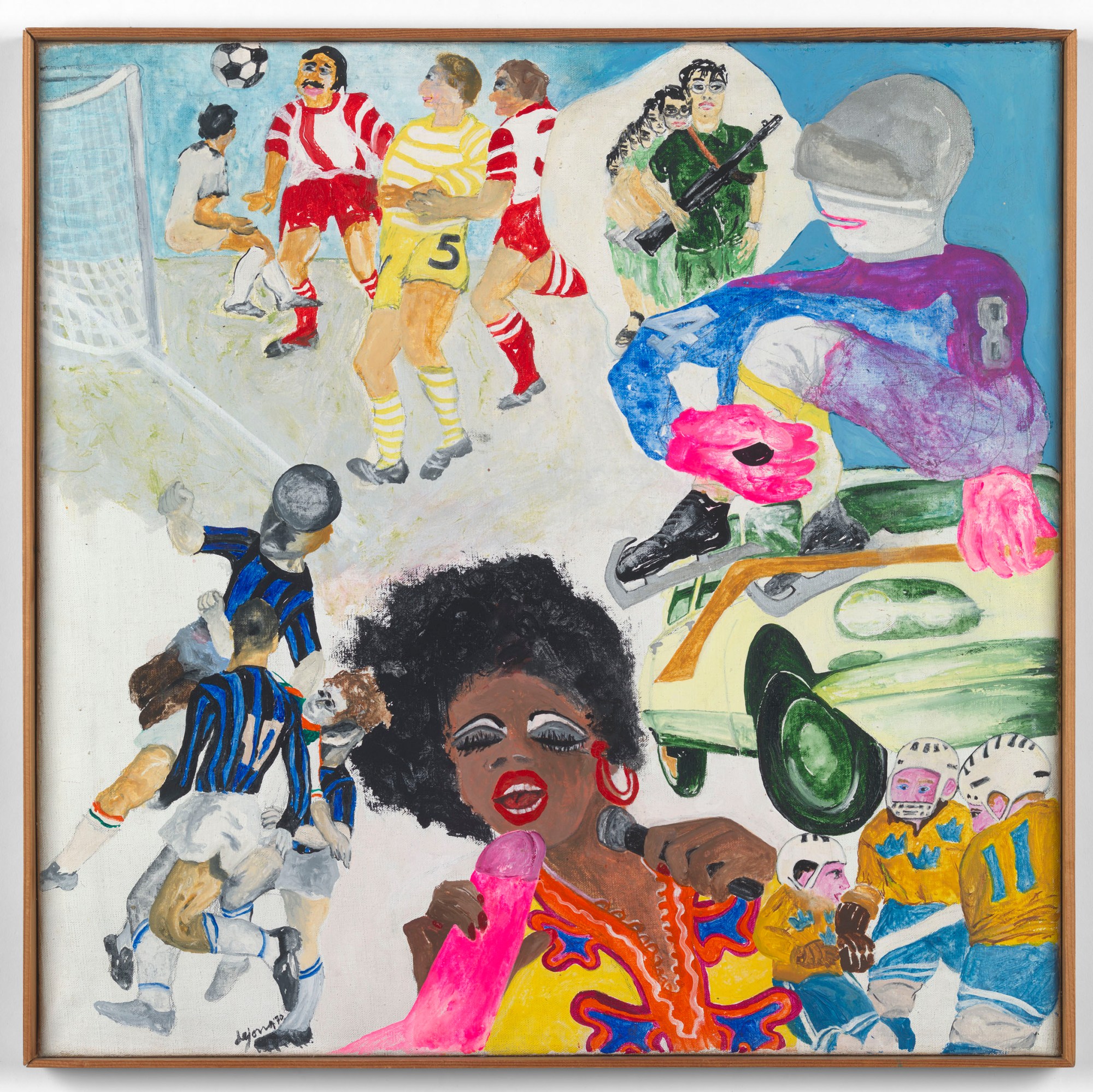

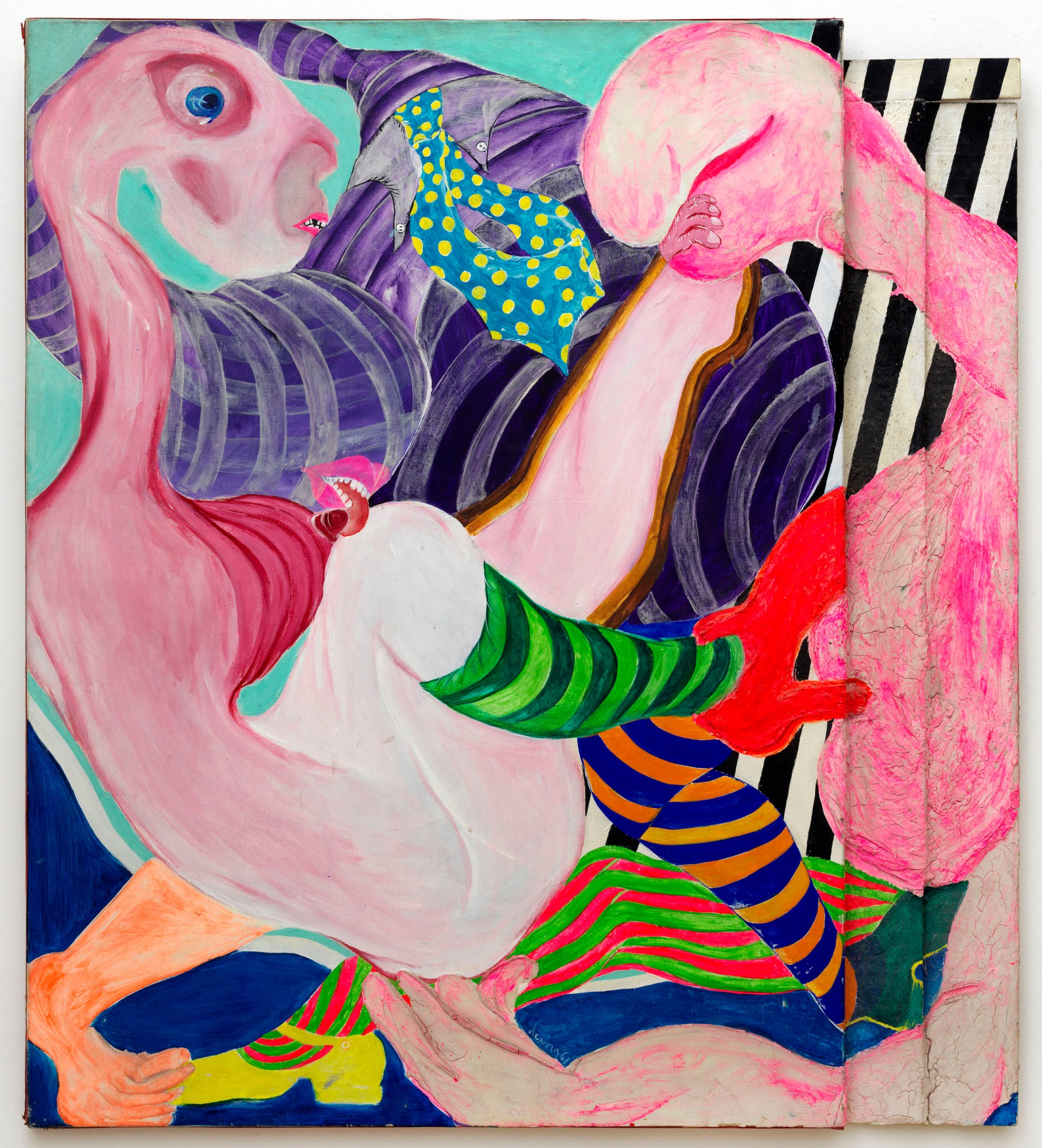

Dutch painter Jacqueline de Jong grew up in an art-loving household: the only privately-owned Willem de Kooning in the Netherlands hung under her childhood roof. At age 18 she moved to Paris and worked at the Christian Dior boutique on Avenue Montaigne (“It was absolute hell working there, but it was good for my French,” she said in an interview). She became one of two female members of the Situationist International, an anti-authoritarian leftist movement founded by Guy Debord. After they met in 1958, he appointed De Jong to head up the Dutch section of the movement, although he dismissed her from the role four years later. Thereafter, De Jong moved back to Paris and, between 1962 and 1967, from her 11th arrondissement apartment, she independently oversaw six issues of an experimental magazine, The Situationist Times. (The now-iconic archive was purchased by the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University a few years ago.) Acting as editor and publisher, as well as establishing its typography and layout, she commissioned multidisciplinary contributions from theater designers, composers, and artists. After the publication ran out of money, she pro-actively made posters during the Paris student uprising of May 68, and her series of erotic paintings from the same era (1966-68) reflect the fluid sexuality and revolutionary politics of the time: a mix of sensuality, sadomasochism, social change and quotidian musings.

Earlier this year, her work was exhibited at Stedelijk Museum—where she’d worked part-time as an adolescent—and she was awarded the Prix AWARE in Paris, which specifically celebrates female artists. Today, she continues to paint in Amsterdam and also cultivates varieties of potatoes on her Bourbonnais farm in France.

Jean Conner

Anglim Gilbert Gallery, San Francisco

Artist Jean Conner moved from Nebraska to Colorado, then eventually all the way west to San Francisco in 1957 with her husband, fellow artist Bruce Conner. The couple took up residence in “Painterland” alongside other creatives (Joan Brown, Wally Hedrick, Jay DeFeo), and partook in the Rat Bastard Protective Association, a community unified by their counterculture lifestyle, their sense of alienation from the mainstream, and shaped by the radical politics of the Beat era.

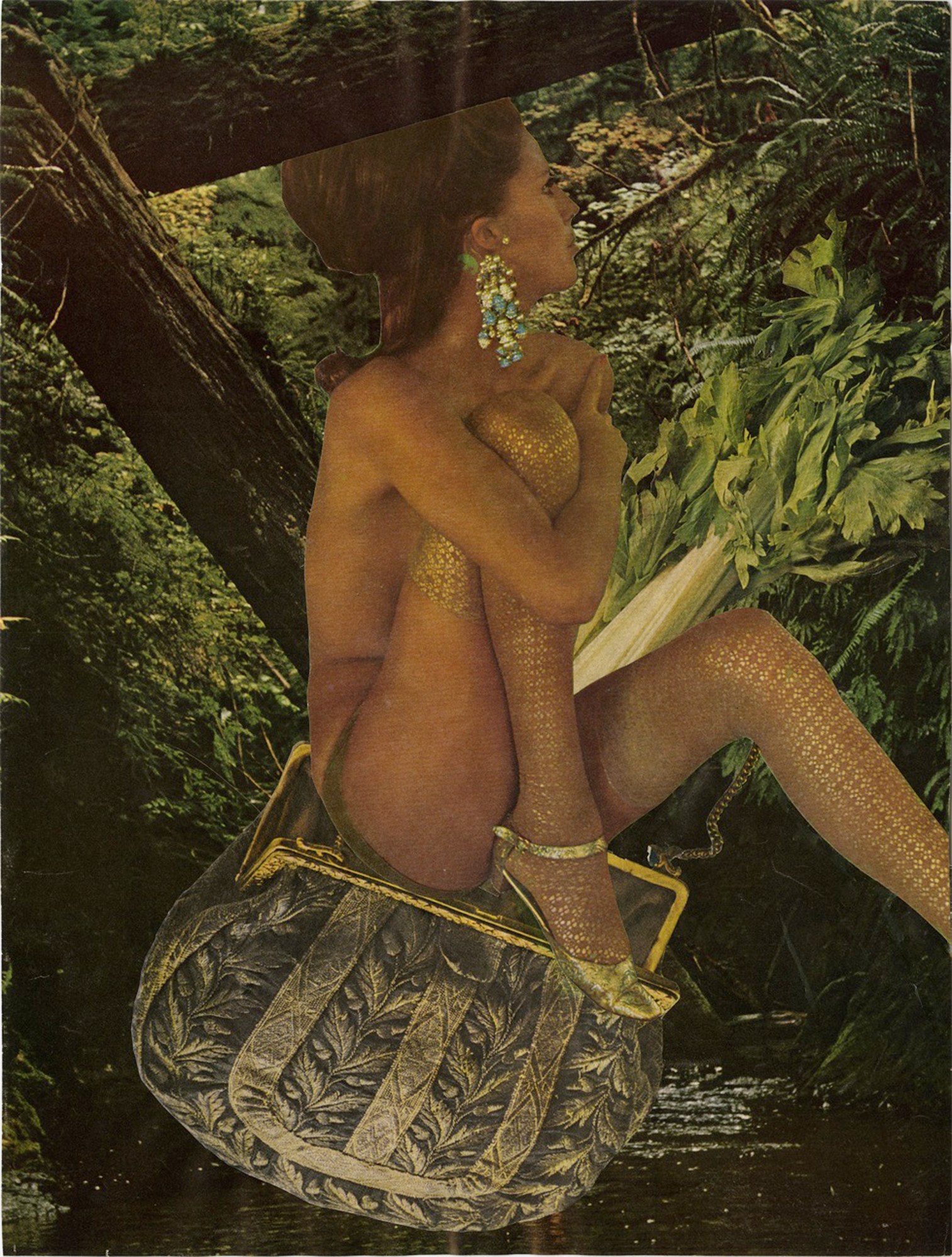

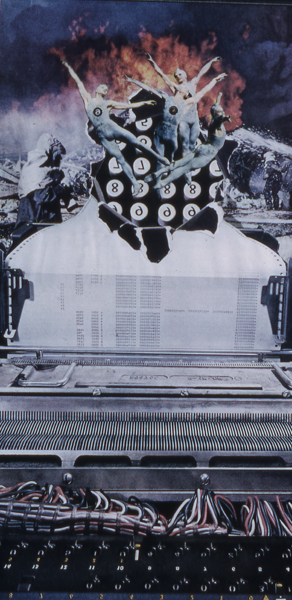

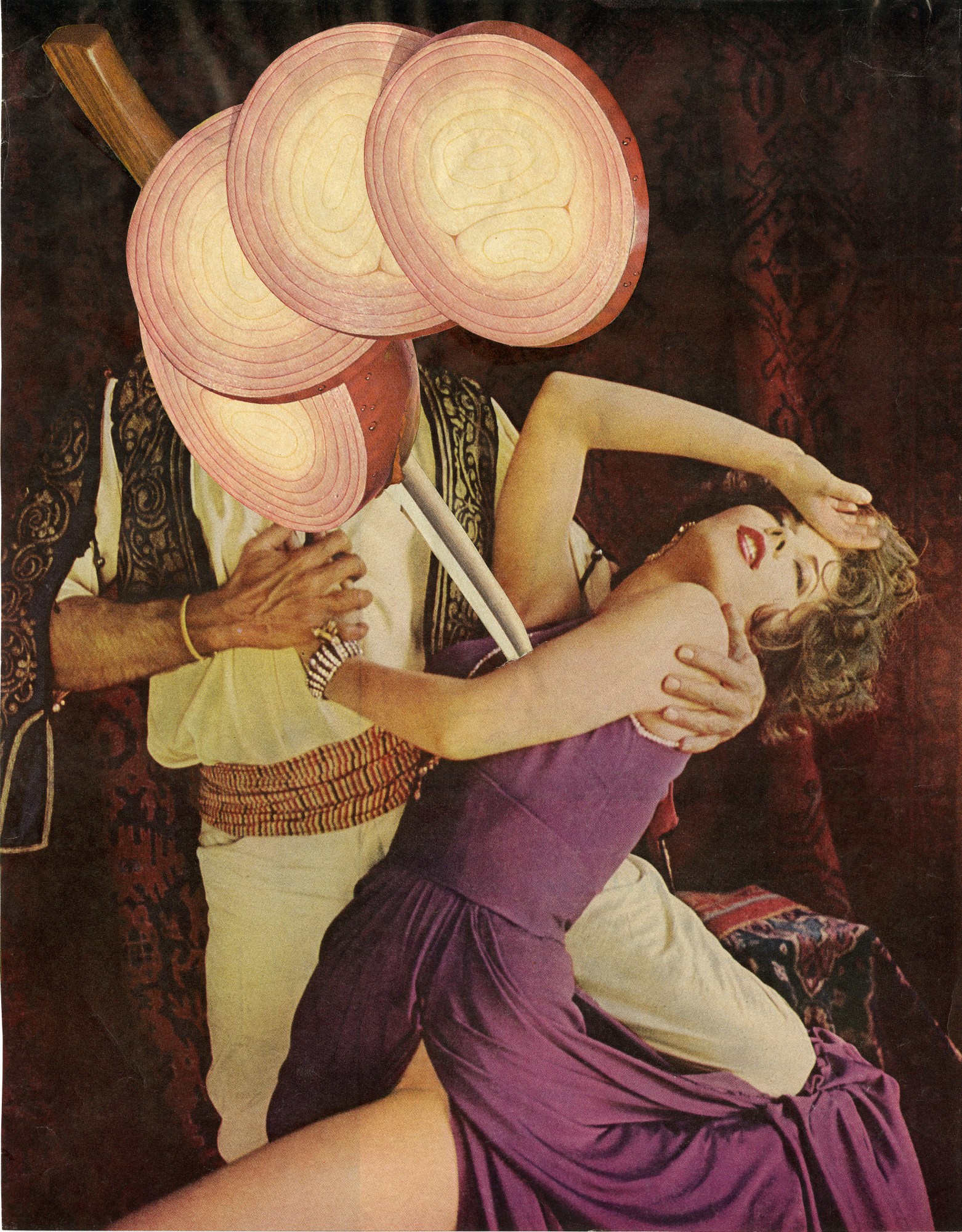

Conner’s collaged compositions skewered American media’s absurdist representation of passively glamorous women. She transformed images she culled from Ladies Home Journal, McCall’s, and Good Housekeeping into playfully outlandish vignettes, pointedly undercutting lusty fantasies by pairing women with odd creatures (hummingbirds, cats, octopi) or placing them in jarring dream-like settings. The expectations around femininity become silly and grotesque, the feminine mystique repurposed for comedic effect. Take a 1978 work by Conner in which a woman swoons into a man’s arm whose his face is obfuscated by slices of red onion: gallantry becomes preposterous. The takeaway is similar from a 1969 work in which four taut women spring out in a puff of fire from an adding machine, or a 1981 work in which a woman clad in thigh-high socks and bejeweled dangly earrings is shown propped on a purse with leafy celery stalk emerging from behind her left hip. Both seduction and feminine fragility are rendered ludicrous—not because women are ludicrous, but because the circumstances in which they’re expected to enact such idealized behavior are.

Conner still lives in San Francisco today; her work is in the permanent collections of the Whitney Museum, SFMOMA, and LACMA. A review of a 2017 group show in which Conner’s work was included noted that her output “anticipate[s] the collages of Martha Rosler by nearly a decade”—and the work also precedes the cheeky feminist photomontages of British artist Linder, a multigenerational sisterhood of harpooning gender expectations.