This article originally appeared on i-D France.

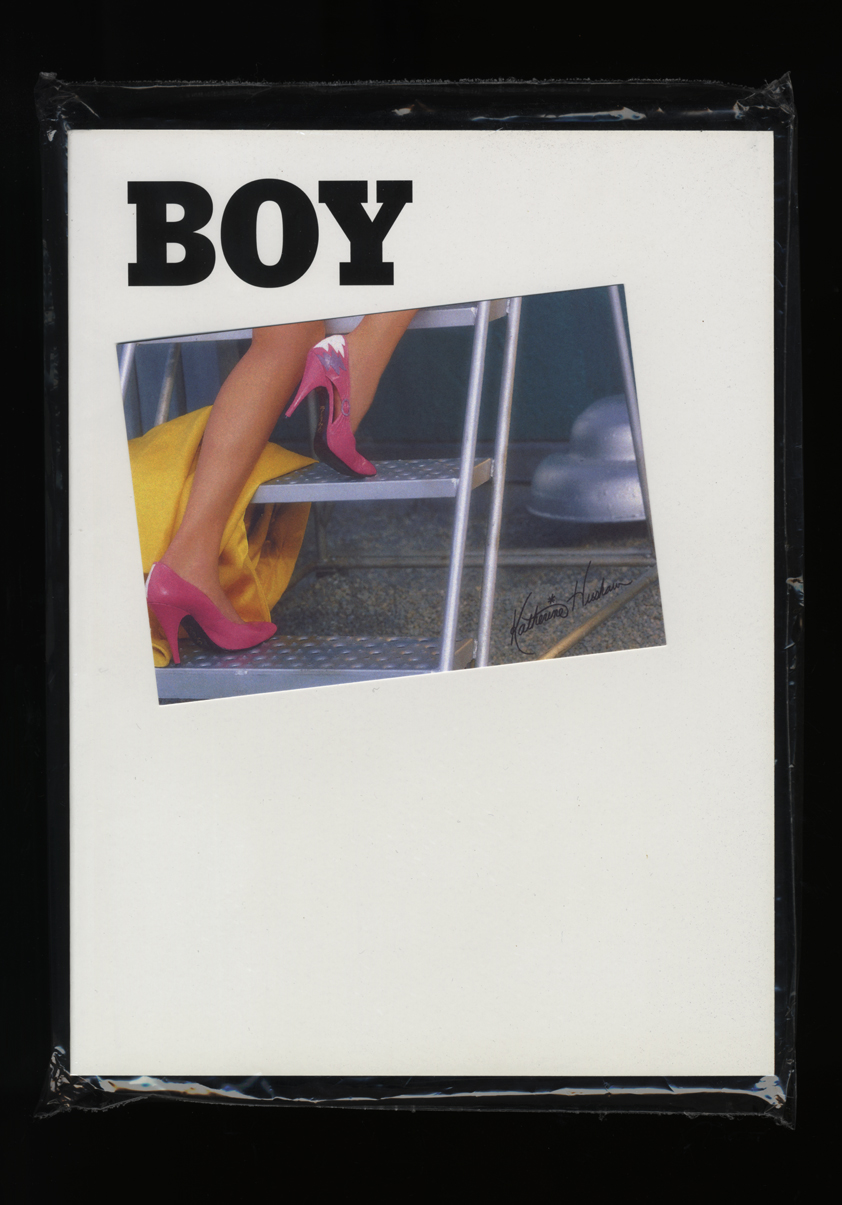

Retrograde or revolutionary, Playboy remains an iconic magazine. The publication evokes cheap perfume and Hollywood glitz just as its founder Hugh Hefner intended. The late owner of the sultry, erotic American magazine — who passed away last September — left behind a controversial heritage. Hefner played a huge role in American culture: he was the creator of “Playmates” and, in the 90s, one of the first to help trans people become visible in Hollywood. He adorned a Playboy cover with the trans model Caroline Tulla Cossey. Whatever you may think of Playboy, the bunny-eared magazine continues to intrigue new generations. Sarah Vadé, a 27-year-old graduate of the Lyon Beaux-Arts Academy in France, dove into the Playboy archives, choosing and gathering hundreds of ads published between 1960 and 2003. From these she created a visual essay entitled Boy, published by Tombolo Press, in which she offers up a new reading of the men’s magazine: A quirky woman’s-eye-view commentary of what constituted heterosexual eye-candy in the 20th century. i-D met with Sarah to find out what Playboy represents to a young, modern woman.

What inspired you to create a visual essay on Playboy magazine?

Originally, it just happened by chance. I was finishing up my studies at the Beaux-Arts, and I was focusing on the imagery of stereotypes — the mechanisms behind it and the exoticism it gives rise to. One of my projects at the time was on Madame Bovary, one of the most translated French novels of all time. I had collected the illustrations from the novel’s cover pages as published in different countries — China, England, the United States — and I realized that in every single country, Flaubert’s heroine was depicted as an archetypal feminine figure. Time after time, she was a muse, seductress, or ingenue — truly a cover girl, 19th-century style! And, as odd as it sounds, one of the “hottest” scenes in the book, the one where she meets her lover Leon on the riverbank, was actually reprinted in a Playboy in 2010. Flaubert’s text was strangely partitioned in the magazine. It was spread over ten or so pages, with a fashion spread in the middle. This editorial bias intrigued me — I needed to know more about this magazine.

How did you get access to all these images from Playboy issues dating from 1960 to today?

It was thanks to the internet that I got hold of the archival images. It was all made possible thanks to an anonymous person whom I thank at the back of the book: One “Tavery80” who carefully scanned all of his Playboy issues from the first page to the last, spanning 1960 to 2003. Thanks to this virtual collector, I had access to more than 150 GB from Playboy US. I soon realized advertising had played a huge role in the magazine’s survival. In 1973, out of 400 pages of Playboy, half [of them were] ads! My eye stopped on the double pages of ads, all without text, that I pulled from the PDFs and rearranged chronologically in my essay. So Boy is a visual commentary on Playboy and the normative representations of male desire that it communicated over the course of nearly 50 years.

Why focus solely on the ads? What led to that editorial choice?

I’ve always been fascinated by advertising imagery. Before I started at the Beaux-Arts in Lyon, I was a visual communications student and I did a lot of work on images. I enjoyed repurposing them, making collages. Each image — and this is all the more flagrant in the case of ads, since they aim to be universal — contains a puzzle, a meaning, hidden references. Images from Épinal travel through time and roam through our flux of contemporary images. What comes to mind is a Dior ad shot by Guy Bourdin, in which the model assumes the famous Kiki de Montparnasse pose shot by Man Ray 30 years prior. I spend my time searching for images on Google, on eBay, in online magazines, and at libraries. The more research I do, the more different topics start to meld together and inform each other. Often it so happens that images evoke one another without me meaning to draw the parallel. It’s super exciting! I’ve always thought of images as being like texts to interpret, hence my use of the term “visual essay” and my choice not to use any text in Boy. I wanted to let the images speak for themselves, while leaving interpretations as open as could be.

How do you see your role as an author when your practice consists of re-appropriation?

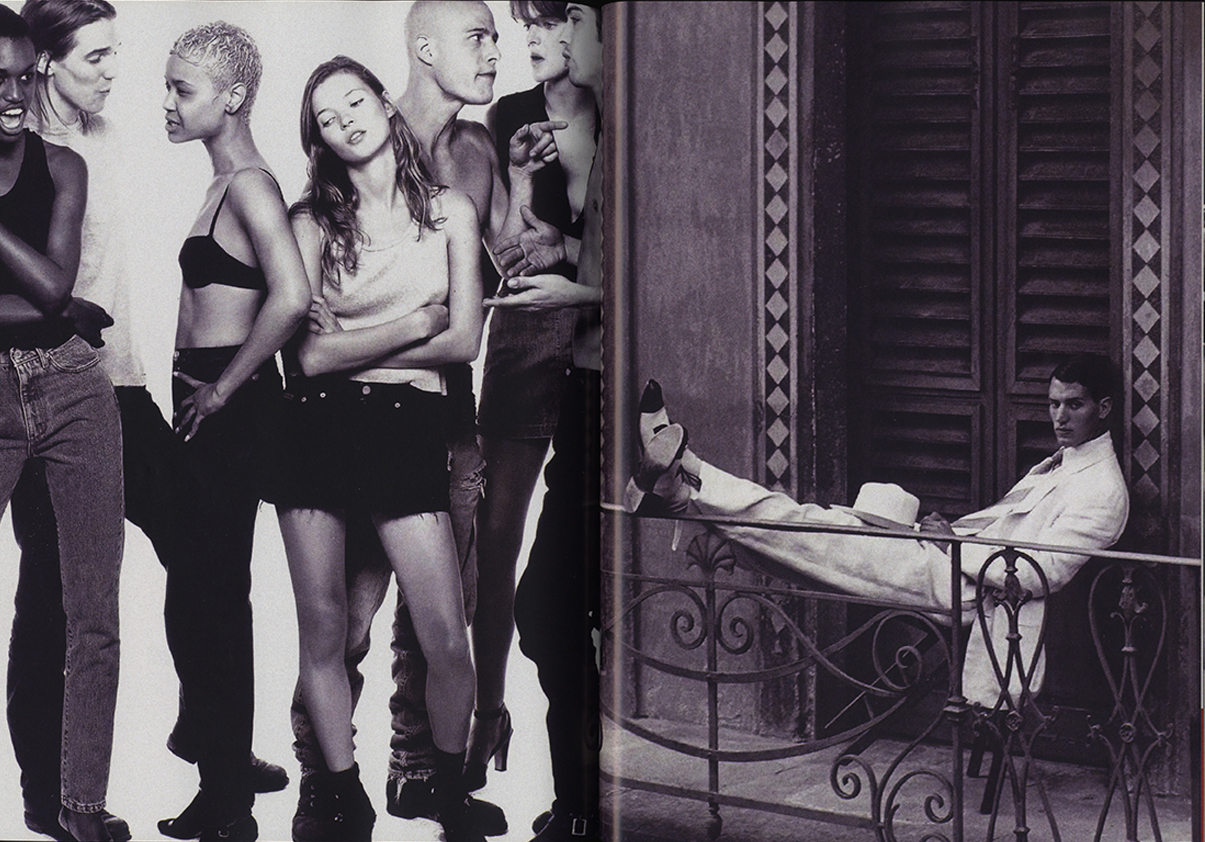

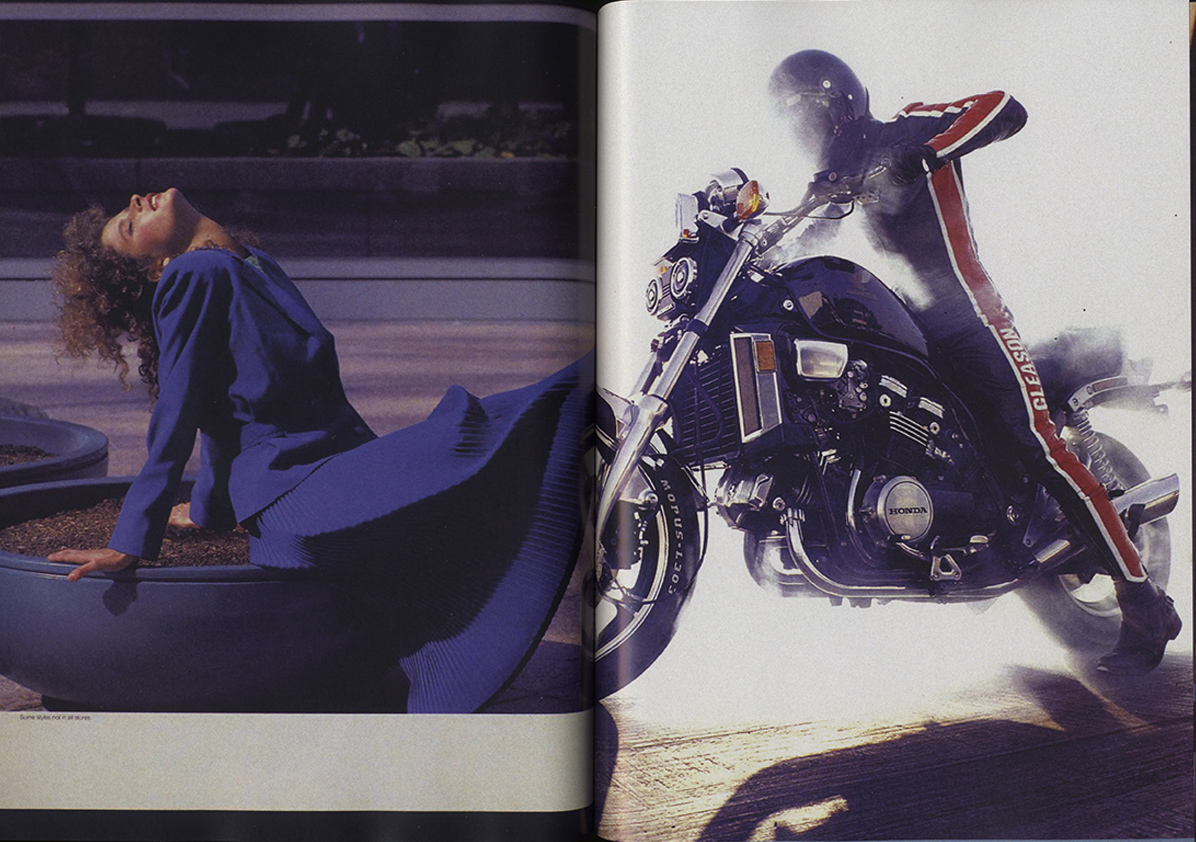

I see myself as an editor here! My training was as a graphic designer and all my work here has been with curating and editing the images. While I’ve held to the chronology of ads that appeared in Playboy from the 60s to today, it mostly was a task of cutting picking and choosing images from the years. I chose to place images side-by-side that had actually come from different ads. The result is a bit offbeat, cynical, and just plain funny. Since my dad works in film, I think I’ve understood the power of editing from a rather young age. I like the idea that you can tell thousands of different stories from the very same pictures.

In your opinion, has the representation of male desire as conveyed by ads evolved over the years?

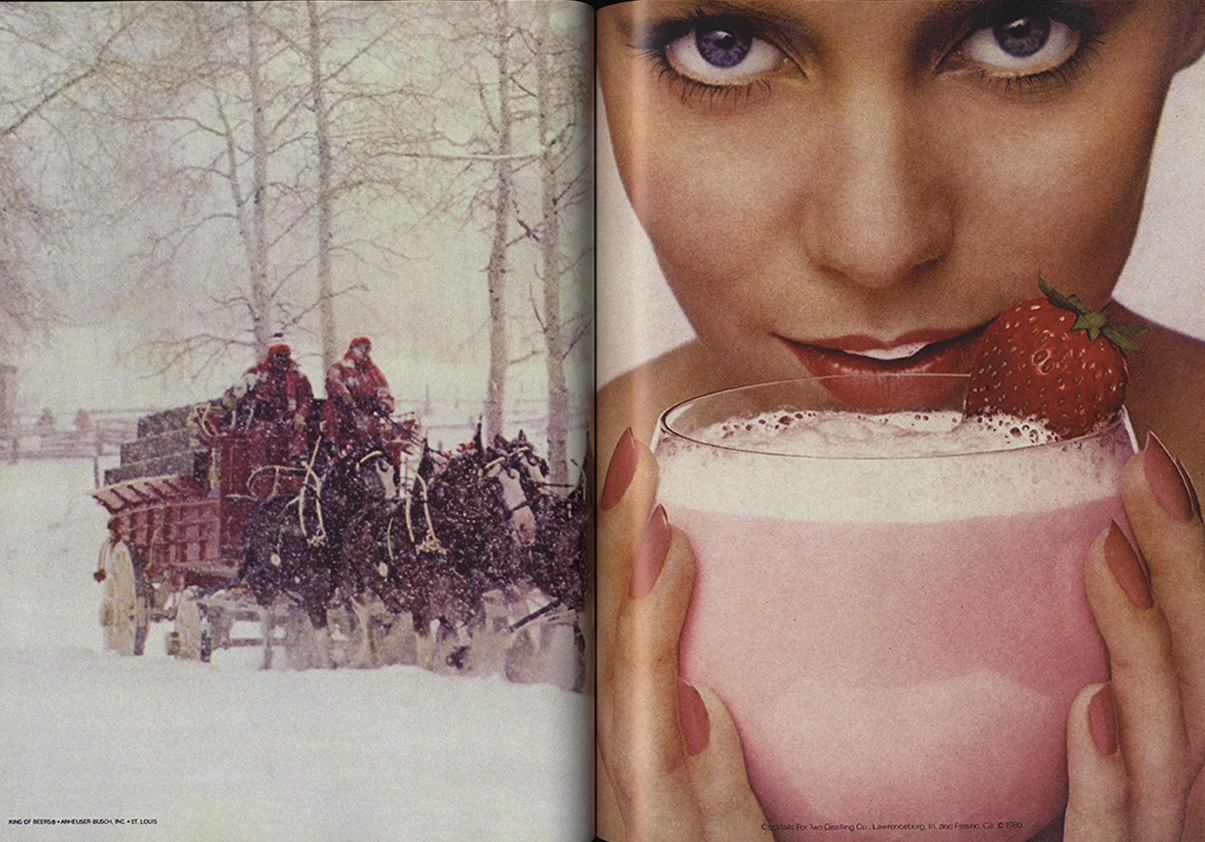

As you leaf through Boy, you’ll realize pretty quickly that over 40 years of advertising, the same icons, and symbols of desire show up year after year! Motorcycles, cars, alcohol, cigarettes, more motorcycles… and a few girls! Only the quality of the photos (since obviously there was the switchover to digital) and the framing of the images have evolved. But truly, it is the homogeneity and the recurrence of these images that made me want to compile them into a book. The figure of the cowboy, for example — the ultimate symbol of masculinity — runs throughout my visual essay, showing up decade after decade. Nothing about that has really changed in 2018, since advertising is still primarily dreamed up and controlled by “the man in full force,” which remains a popular phrase even if the current trend is toward equality between the sexes.

As a woman, what’s your view of these rather “stereotypical” portrayals of masculine desire?

I find them funny. I think Boy would have looked totally different if a heterosexual man had created it. But after all’s said and done, I don’t think I truly favored a “feminist” reading of Playboy. The idea wasn’t to ridicule the ads of the era either. It was more to put the spotlight on recurring symbols and themes. I also wanted to talk about Playboy in a new way. For my generation (and maybe even more so for later ones), Playboy evokes an image of stark-naked Playmates wearing bunny ears. In the end, very few have seen it from another angle — aside from Hugh Hefner, perhaps. And yet, at its core, Playboy was revolutionary. When Hugh Hefner dreamed it up, in the 50s at the peak of McCarthyism, its style was very much “American way of life.” The parameters of male happiness were extremely strict, traditional even: job, marriage, house, family, and dog. Whereas from its very first issues, Playboy asserted the figure of the independent single man, who enjoyed good music, appreciated style, and drank cocktails while ogling girls. This thought seems very elitist today, but at the time, it was nonconformist. In 1953, you’d fold up your Playboy so as to hide the title, and magazine sellers would deftly slip it into brown paper before handing it to customers. It was shameful to buy a magazine like that back then. Around 1970, what with the wake of the porno industry and the liberation of morals, the figure of the urban bachelor became much more socially acceptable — glorified even! Buying Playboy wasn’t scandalous anymore. That was the era when Playboy descended into the vulgar, “ass” iconography we associate with it today.

What are you working on right now?

A friend and I are doing a project on Emmanuelle, the iconic [French] 70s porno film. The idea is to construct visual and textual links between the film’s imagery and ads from the era that targeted women. As we were picking and collecting ads for lingerie, appliances, and beauty products from between 1972 and 1976, we realized that they were just as sultry — maybe more so — than the poster for Emmanuelle, a pornographic film. The models from the era were showcased like Playmates. The sheer proliferation of this style was all the more shocking! Funnier still, it turns out the poster for Emmanuelle looks a lot like a Pier Imports ad from the same period. I haven’t gone on vacation for five years, but as you can see, I travel plenty behind my computer.