Where once poetry spoke of pleasant sceneries and the despair of the broken hearted, today there isn’t a single issue or emotion that’s not being referenced in one form or another. Sex, gender, violence, identity, racism, the refugee crisis, Brexit. No subject matter is off limits. What’s more, this new wave of young poets are doing it with the kind of empathy and honesty that speaks to an entire generation.

Now has never been a more exciting time for poetry. Especially when you have the likes of Blood Orange sampling Atlanta poet Ashlee Haze’s For Colored Girls (The Missy Elliott Poem) on the opening track of his album Freetown or Queen Bey reading prose by Warsan Shire throughout Lemonade.

Then you have London’s foremost cultural institutions like the ICA, Southbank and Roundhouse staging poetry residencies and events, while underground spoken poetry nights like Steez, Boxedin and Jawdance are cropping up all over London. Not to mention a rise in forward-thinking independent publishers such as Clinic, Test Centre and New River Press, who are breathing new life into the way we disseminate poetry.

In a world of fast culture and false truths, poetry has never been more essential. Through its diverse perspectives we come to learn of new things, of our similarities and differences, both of which are cause for celebration. Speaking of celebrations, to mark National Poetry Day, we’ve shone a spotlight on five new gen poets tearing up the rule book.

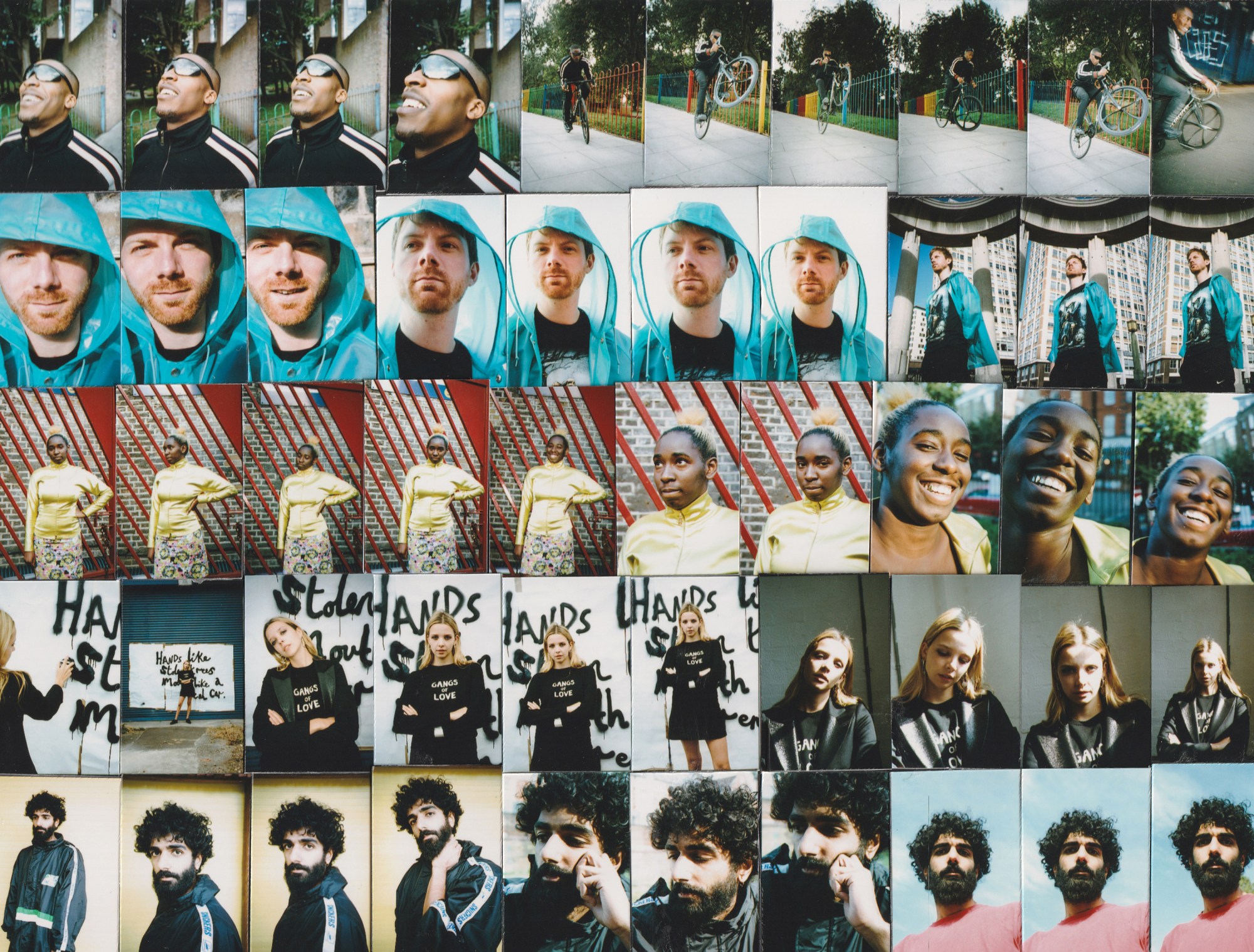

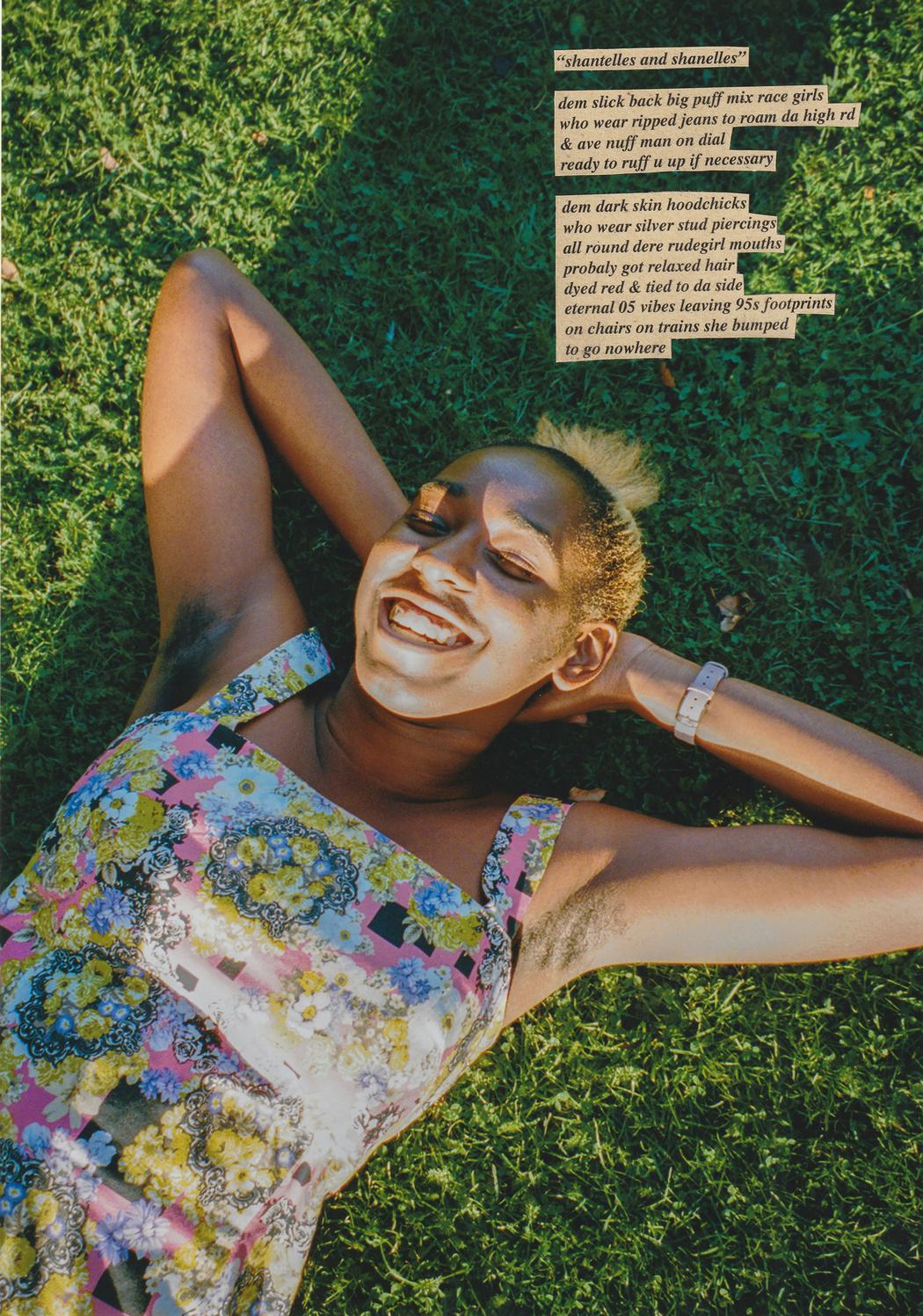

Abondance Matanda

After taking a Year 10 poetry project about Black History Month to heart, Abondance Matanda found a vocation where she could freely explore her identity and hasn’t looked back since. At school she amassed a number of poems on her phone and laptop and decided to put them in a collection. “I made around 200 books with nine poems in, rinsing all of the printers at school during my GCSE exams.” Inspired by the punk movement, DIY culture and independent publishing, she made her books by stapling pages together, hand-painting the covers, and selling them at friends’ parties and zine fairs.

After reading works by Grace Nichols and Alice Walker, Abondance began focusing on works by black women. “I felt more connected to them.” she explains. “From Grace’s poetry to the lyrics of Ms Dynamite, you can trace what it’s been like to be a black British girl over the years”.

In continuing the legacy of her idols, Abondance’s poetry discusses her experience as a black working class female, the notion of girlhood and her coming of age experiences growing up in Tottenham. “In the same way I’ve been inspired, it excites me to think someone could read my work and want to start writing,” she says. “If you’re writing about something specific, it can connect to someone’s experience and they might feel less alone in some way.”

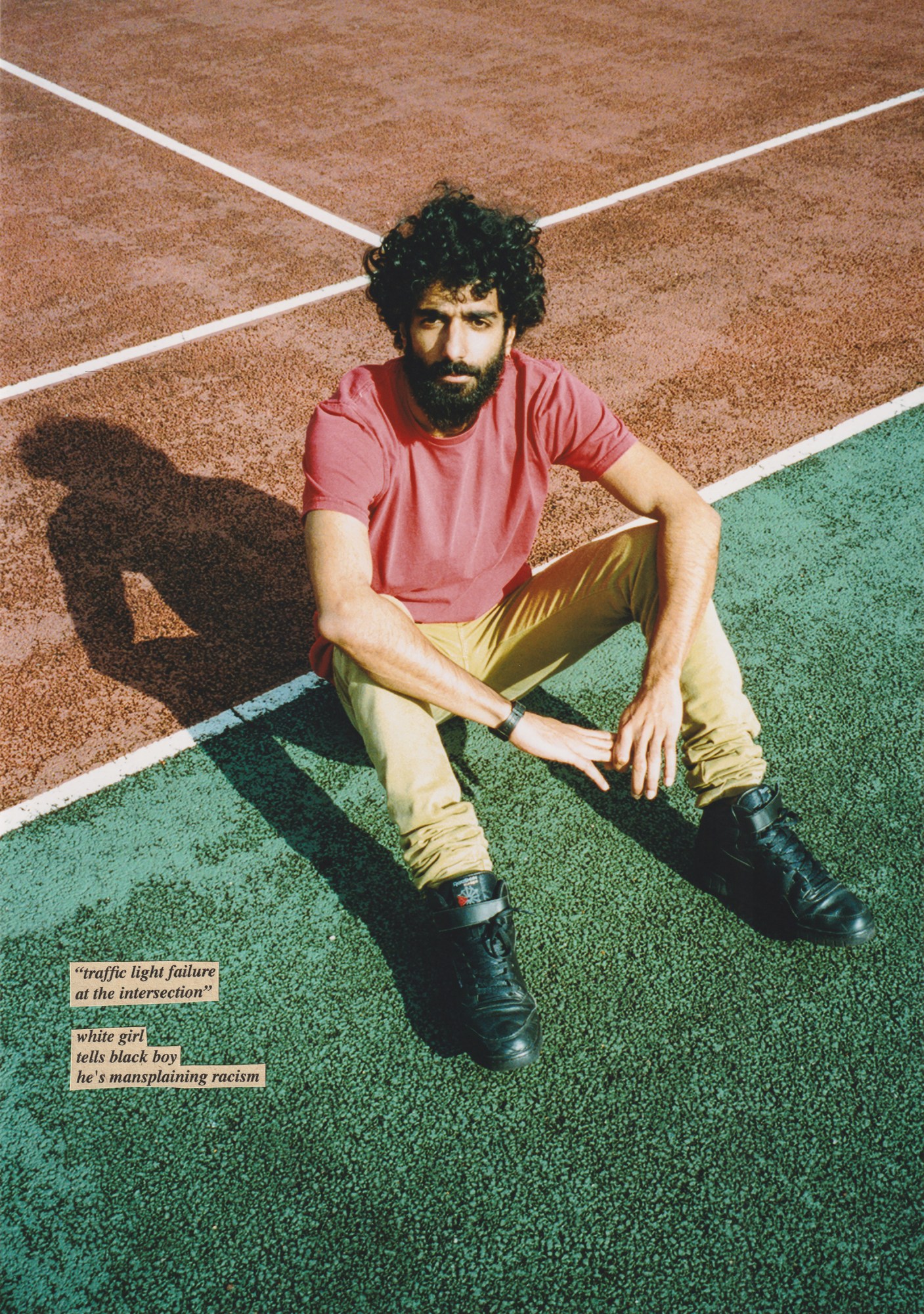

Zia Ahmed

London laureate Zia Ahmed recalls a childhood growing up in Cricklewood and Kilburn where poetry was common practice: “I have a vivid memory of being around seven, walking into a room where a group of Pakistani men were sat around quoting poetry to each other, almost as a release for them after a day’s work.”

Spurred on by that same sense of catharsis, Zia describes the act of reading aloud his poems about being a young, working class, British, Pakistani, Muslim in London as “a release of tension. When you get on stage, that’s your space, your time.”

After watching a friend perform as part of the 16-25 year old Roundhouse Poetry Collective, Zia knew he had to join. Three terms and one fruitful year later, and Zia had built himself a name on the spoken word circuit. “Spoken word is a springboard into so many different forms,” he says. “You start off with spoken word and can progress into music, stand up comedy, theatre.”

Thanks to a bursary from the Channel 4 Playwright’s Scheme, Zia is in the process of completing a play with the Paines Plough theatre company. Like most of his work, the play will manoeuver his own thoughts and interactions based on his background and heritage. “When there’s confusion and boundaries in your daily existence, which I think our generation feels more today, there’s something about a poem that can bring groundedness and understanding,” he muses. “Poetry isn’t just stacks and facts, it’s more abstract and feeling.”

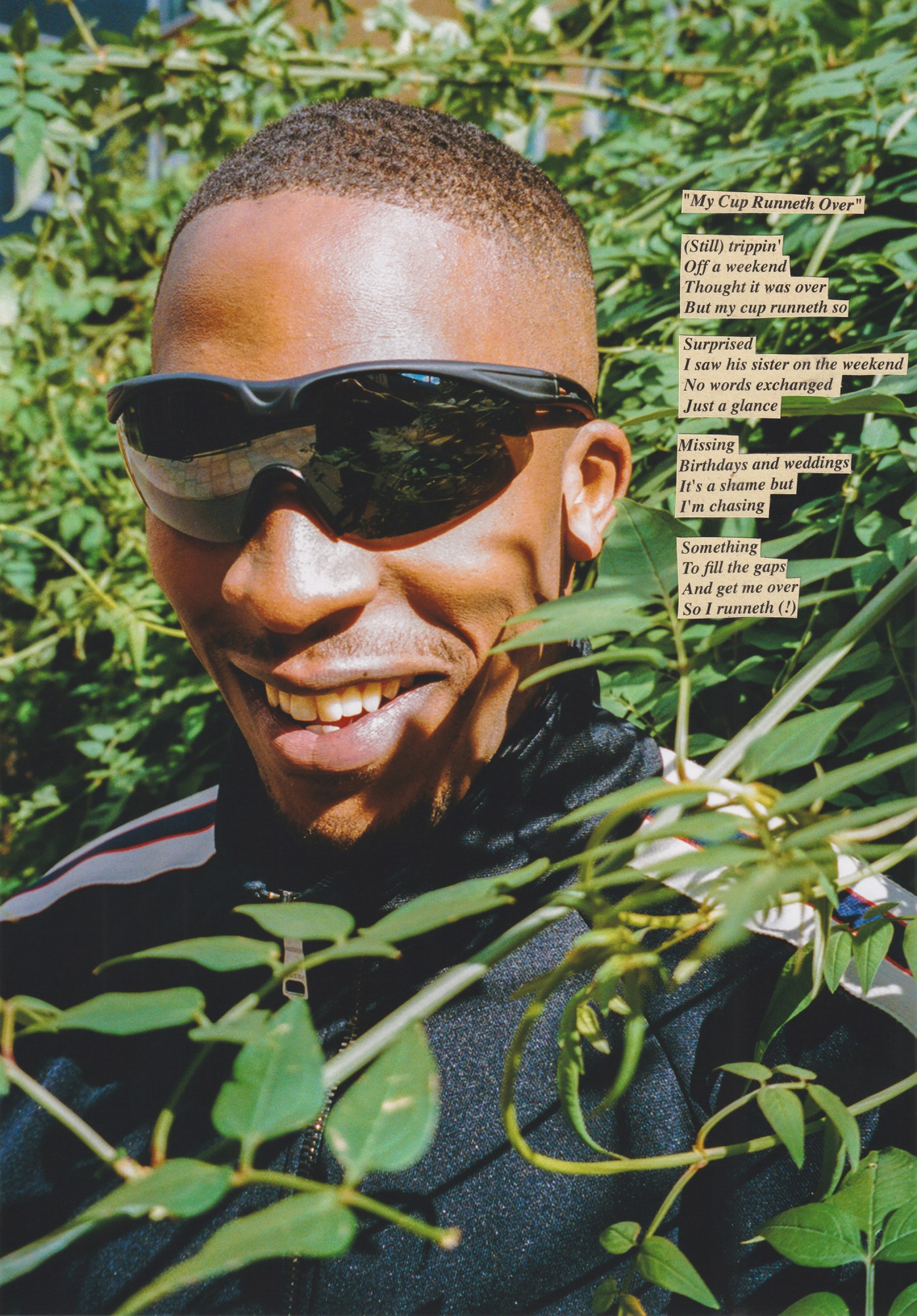

James Massiah

At the age of 12, James Massiah started writing poems about his faith and reading them aloud in church. By the time he was 18, he became “jaded and cynical with religion and so my poems were packed with hidden meaning – I’d be reading them out with my own private dialogue happening.” The church soon noticed, dubbed James a false prophet and banned him from reading at any church in the city.

A short hiatus followed before he began performing again, first for friends and university shows, later at local spoken word nights like Sunday Show, Kid I Wrote Back and the still running Steez.

His poetry acts as a means to observe and commentate, not from a place of authority, but from a perspective he describes as “the court jester who’s standing in the gap between the king and the subjects.” He talks about his own experiences of morality, mortality and sexuality in a comic, tongue in cheek, wink in the eye, sort of way.

His forthcoming project is an album of 27 recorded poems called Euthanasia Party 27. “There was a way of doing it that was broadly understood but I wanted to create this for people who want something deeper,” he says. “I want to be the poet for those people who have dealt with some issue or experience in life and want to dig, and so find me down there.”

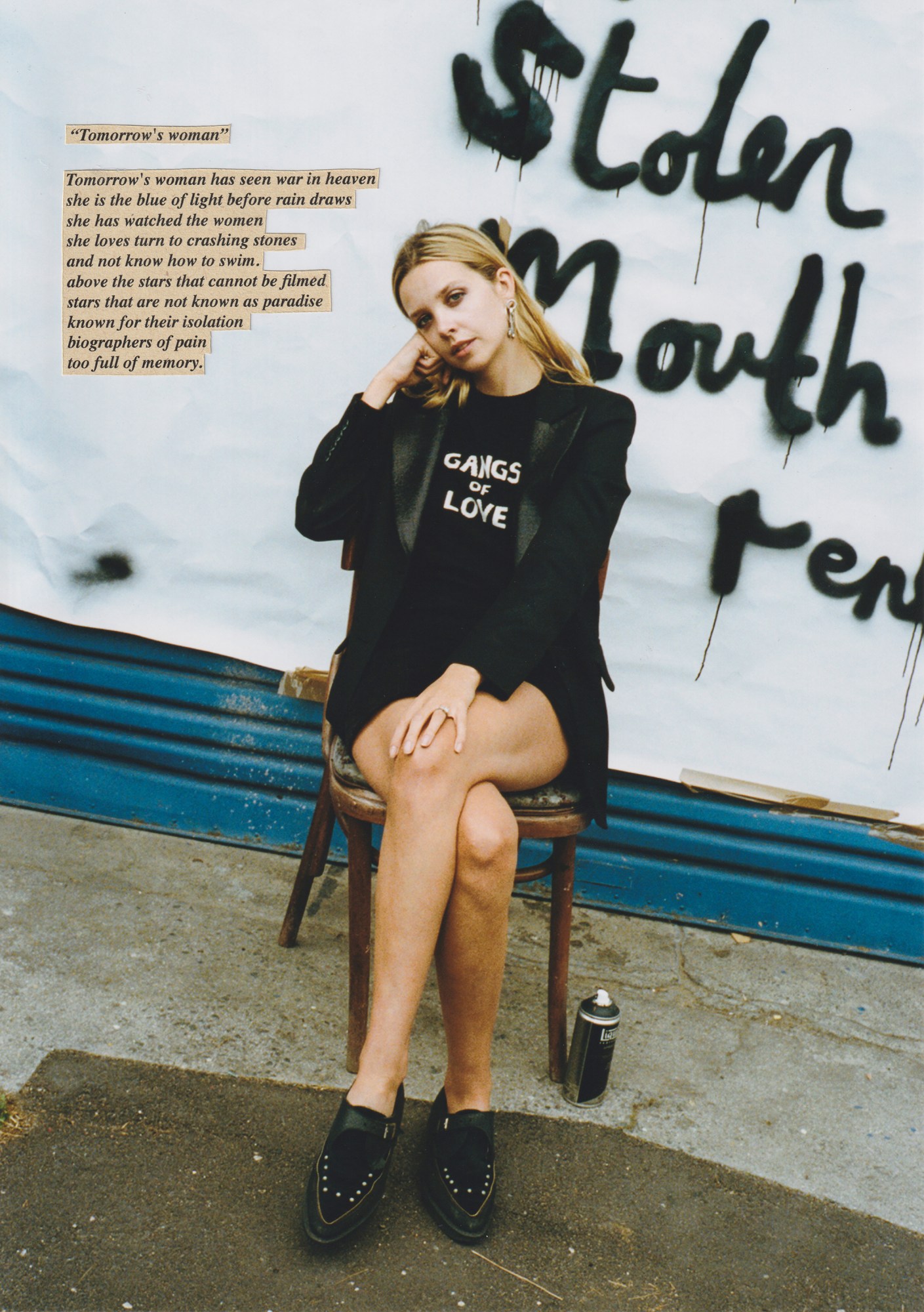

Greta Bellamacina

Greta Bellamacina began writing poems as an outlet for the quietly raging world inside her head. “As I’ve gotten older, I feel more compelled to write about the world we live in,” she says. “It’s a writer’s responsibility.” The unfair representation of power and a distorted media is something Greta writes about often, notably in the collaborative collection she wrote with her husband, the artist and poet Robert Montgomery, Points For Time In the Sky.

Her most recent book Perishing Tame questions identity: “What it means to be female, to live in a world that still uses the terms like ‘others’. I wrote a lot of poems about the refugee crisis.”

As a means of supporting and nurturing other poets Robert and Greta set up New River Press. All poets receive 50% of profits from their sales. Both naturally drawn to the unheard and surreal, they wanted to celebrate those who “weren’t being published, like our literary hero Heathcote Williams, because their work was considered too political, too irreverent.”

Afterlight, Greta’s forthcoming collection due for release next year, sets about rejecting conventional ideas of aspiration in favour of regaining an adolescent sense of love, mystery and place.

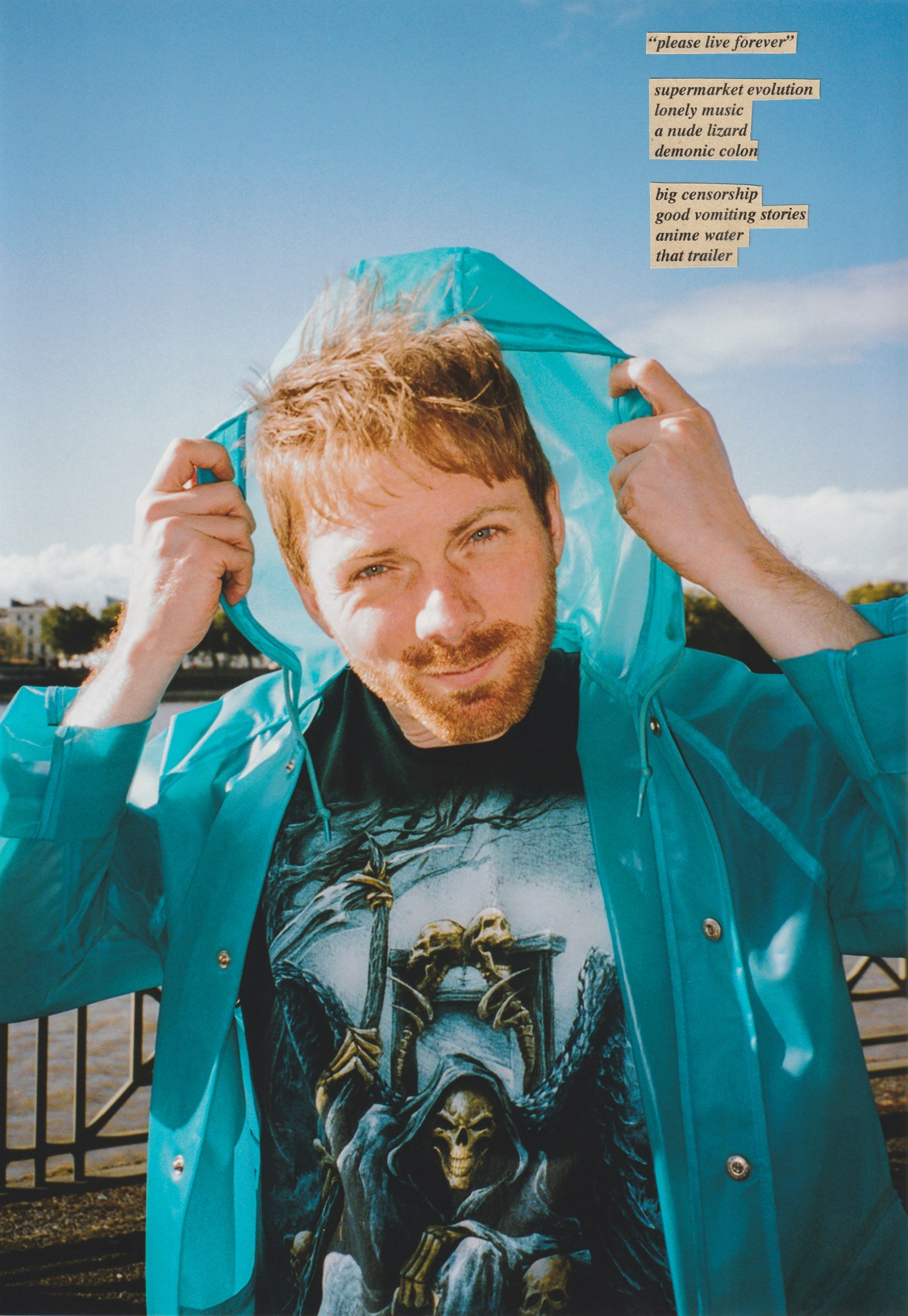

Crispin Best

It’s hard to believe that Crispin Best once hated poetry. Or at least he thought he did. However, after studying a Masters in Fiction at Manchester University, he had a change of heart, finding “poetry was so much more fun, communal and instant.”

With most of his output on the internet, Crispin had little IRL work published until he was selected as a Faber New Poet, publishing his first collection with them last year. Another real life book followed, this time through his friend and poet Sam Riviere’s If a Leaf Falls micro press, a collection of OkCupid profiles of those with whom he had over 90 percent match or 90 percent enemy ratings.

The way in which people use language to achieve an effect on the internet, writer or not, is integral to Crispin’s practice. His thousand line poem shows you only eight lines at a time, randomised, so if you stay there long enough you’ll read a unique version of the whole thing. Like most of Crispin’s work, the poem refers back to his favourite medium: “My definition of the internet is like this: you’ll have 15 tabs open, a video of some lecture about hallucinogenic drugs there, emails over here, twitter over there, a constant bombarded of stuff,” he says. “I think I’m trying to represent that – that everything’s at your fingertips at any time.”