As the newest wave of feminism has galvanized women to rethink their place in the society of 2018, the flip side feels just as urgent to address: what does it mean to be a man today? How gendered identity is being redefined and deconstructed is a deeply human, social, and artistic inquiry. All That Man Is – Fashion and Masculinity Now, a group exhibition curated by Chiara Bardelli Nonino for the third edition of the Photo Vogue Festival, includes over 50 photographers with diverse visions and projects. Each one explores the complexities of manhood through photography — a medium that deftly mixes art, documentary, and portraiture in an evocative and empathetic way. Exploring a sliding scale of empowerment and vulnerability, these five photographers remove any stereotype or stigma of sensitivity, recontextualizing gendered identity for today’s world.

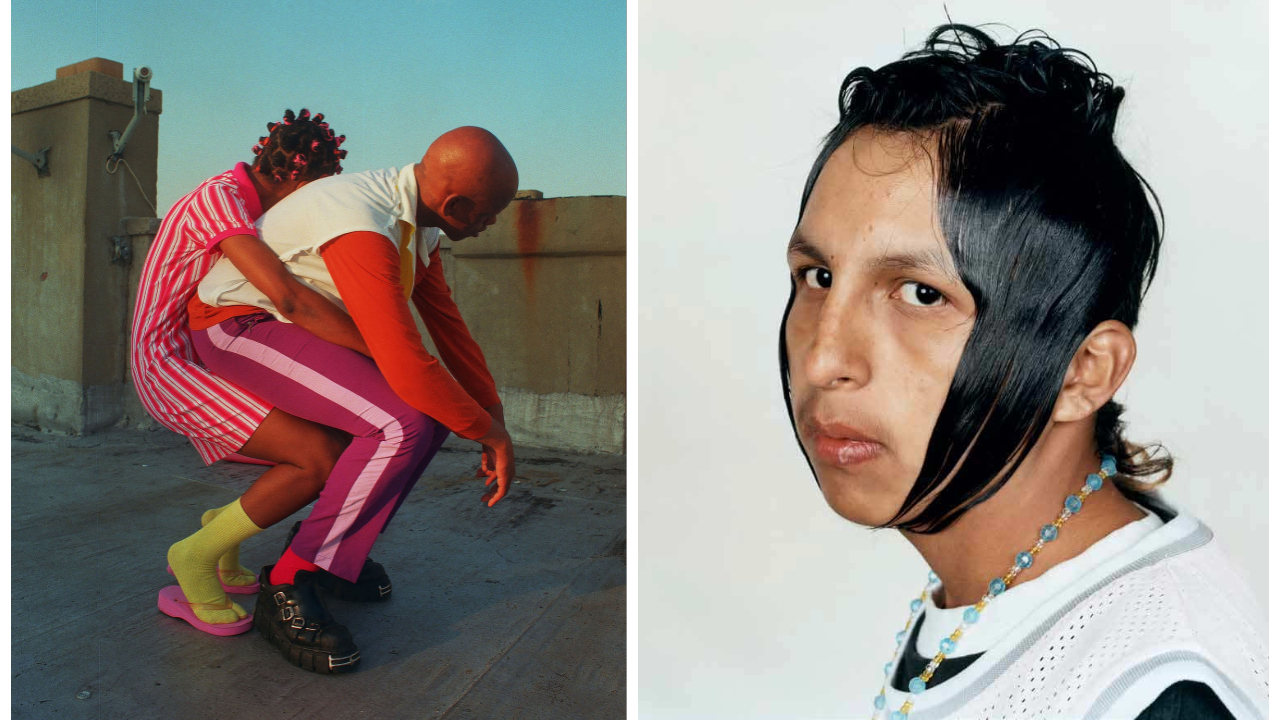

Arielle Bobb-Willis

New York City native Arielle Bobb-Willis has developed a striking visual language that reshapes the silhouette of the body and almost suspends distinctions between male and female altogether. Her portfolio stands at the crossroads of vivacious fashion shoot and avant-garde choreography. “Within my work you can’t distinguish gender and it’s more about appreciating the art and full composition for what it is. Gender fluidity is real and I think it’s important that we are sensitive and understanding to how people see themselves,” she says. Showing a favorite photo from a L’Uomo Vogue cover story, she notes that gender is “so specific to each person you shoot or interact with, so it’s an ongoing exploration of feelings, expression, and individualism.” Bobb-Willis is inspired by her three younger siblings, all under the age of 12, whose perception of the gender binary is much more adaptable. Ultimately, she says, “through the eyes of artists… we can share what [gender] means to us personally, rather than what the world tells us it’s supposed to be.”

Olgaç Bozalp

“It’s very interesting to see how cultures and regions can shape gender,” notes Turkish-born, London-based photographer Olgaç Bozalp. “Photography, as all mediums of art, can create awareness of how we view gender on a large scale and can ignite a dialogue to push for change.” In 2016, Bozalp shot a series about Turkish men shot in Istanbul in 2016 in collaboration with Gucci, which included a mustachioed man in a bright pink ruffled shirt on a Peugeot scooter, and a man sporting beige flares and a pink floral print upon a yellow shirt. His backdrops range from luminous natural landscapes to faded pastel-painted walls, before which men pose confidently in unexpected, elegant silhouettes: billowing trousers or wraps snuggly tied at the waist. He has photographed belly dancers and the artist Grayson Perry, but his Instagram also features his dad, a nod to the fact that, if you’re lucky, the best icons of masculinity are the ones that surround you.

Micaiah Carter

Micaiah Cater, who has shot Kehinde Wiley for the Time 100 and the Thom Browne Golf’s fall/winter 18 campaign , is showing an image that stemmed from his thesis as an undergrad at Parsons. Called 95/48, it contrasts his father’s 20-something years in the 70s with to the photographer’s own experience navigating that same age range decades later in Brooklyn. “I was heavily inspired by scrapbooks he made from his travels in the military,” Carter said of the black-and-white images he consulted. “I feel in love with the tones and Black Power movement, and took that as inspiration for my own work.” While the past provides a point of fascination, Carter is grateful for the ways in which the contemporary era has made room for nuance. “I think there is now a chance for men to not be boxed in to what society thinks a man is. Gay, straight, or trans, I think it’s so amazing how we are being able to see all different perspectives in bigger platforms of representation.”

Stefan Ruiz

Stefan Ruiz studied painting and sculpture in California and Italy before becoming a photographer. He has explored Mexican culture in various ways. The picture included in Masculinity Now is from his series Cholombianos, in which he photographed members of the Monterrey subculture at a makeshift studio outside the clubs they frequented. The Cholombianos fixated on cumbia rebajada — music from the north coast of Colombia with longstanding roots in African, indigenous, and Spanish music, reimagined in “a slowed-down version, similar to how dub is a remix of reggae,” Ruiz explained. The devotion to this instrumentation was complemented by the group’s idiosyncratic hairstyles and hand-painted sartorial signatures: “a combination of American streetwear, Mexican religious iconography, and bits of traditional Colombian coastal dress.” Because they came from underprivileged neighborhoods and looked completely distinctive from the rest of the community, they were ostracized and targeted by police, accused of being runners for the cartels’ U.S.-bound drug routes. “The scene has since disappeared from view,” Ruiz noted. “They were easy to spot because of their haircuts, so they stopped wearing them.” Nonetheless, he notes the unparalleled style of these kids “still has a mythic life in Mexico” and lives on as “viral memes online.”

Scarlett Coten

For four years, French photographer Scarlett Coten shot portraits of young men from countries throughout the Mediterranean Basin — encompassing communities in Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, and Morocco — entitled Mectoub. She began the series in 2012 in the wake of the Arab spring, which seemed to announce an era of “greater individual liberty, noting “that desire for liberty affirms who they want to be as men.” It’s a new generation dealing with the liminal: the title of the series is a play on the Arab word “mektoub” (meaning “it is written”) and the French word “mec” (meaning “guy”). Coten’s series anatomizes the idea that masculinity has to be inscribed into certain stereotypes or assumptions. She has since moved on to shooting a series about American men, Plan Américain, and has found many echoes despite the change in geographical context. “As a woman looking at a man in an intimate way, they can let go, can abandon themselves to be closer to who they are. People say they’re showing their feminine side, but sensitivity is not feminine.” Of the two projects, she said, “I’m returning to this same preoccupation: men’s identity is theirs to appropriate for themselves however they want.”