Over the past 20 months, much of the world — although, unfortunately not the fossil fuel industry — seems to have developed a sudden, collective appreciation for nature. As our movement was limited, we longed to be deep in the countryside, by the sea, in a forest, with animals. We craved a space to plant, grow and nurture living things. Time had slowed down and priorities shifted. This is what inspired London collective Baesianz to curate ROOTS, an exhibition and event series exploring “nature, its healing qualities and the decolonisation of horticulture through the work and voices of Asian artists”.

ROOTS is a collaboration with Grubber, a South London community organisation born mid-lockdown as a plant exchange, through which individuals would deliver propagated plants to others in their neighbourhood. “Grubber looks to spread the joy of nature to as many as possible, making it more accessible, and teaching of its boundless benefits,” explain the team behind Baesianz. “Our mission is to amplify the art and voices of Asian heritage artists from around the world, celebrating our roots and creating deeper connections with them in the process. When you put those two aims together and throw in a pandemic — during which nature has been a saviour for most of us — it just felt right for nature to be the focus here.”

This weekend, ROOTS will take over Art Hub Gallery in Deptford, South London, with an exhibition of photographs, paintings, sound installations, live performances, an actual garden, a workshop exploring Ayurvedic and traditional Chinese medicine, a grounding yoga class and a whole lot more. “When talking about nature from the Asian perspective, it felt very important to focus on both its healing capabilities and the need to decolonise the way this information is usually disseminated,” Baesianz explain. “Many Asian cultures have such a strong connection to nature, with understandings and beliefs that aren’t widely understood or sustained in the west. We wanted to cultivate a space for Asian artists and communities whose practices involve nature, a place where knowledge is exchanged.”

The aim, Baesianz say, is for people to leave with “a desire to make more time and space for nature in whatever capacity feels right for them; to leave with a better awareness of how to find nature’s healing capacity; and to continue to look beyond dominant western understanding”. Keen to learn more about ROOTS, we spoke with a number of featured artists about their contribution to the project, their relationships with nature, and the ways in which we can all work towards decolonising nature together.

Peng Jiahao, 27, Los Angeles

Tell us a bit about yourself.

I’m a visual artist born and raised in Wenling, China, and now existing and shooting in Los Angeles. I received my MFA from Columbus College of Art and Design in 2019. My works underscore all things tender, probing in daily life, oftentimes involving marginalised, horticultural, queer, and trifling subjects. I’m also the gallery associate at Diane Rosenstein Gallery in Hollywood, CA.

Talk us through your contribution to ROOTS and the story behind the works.

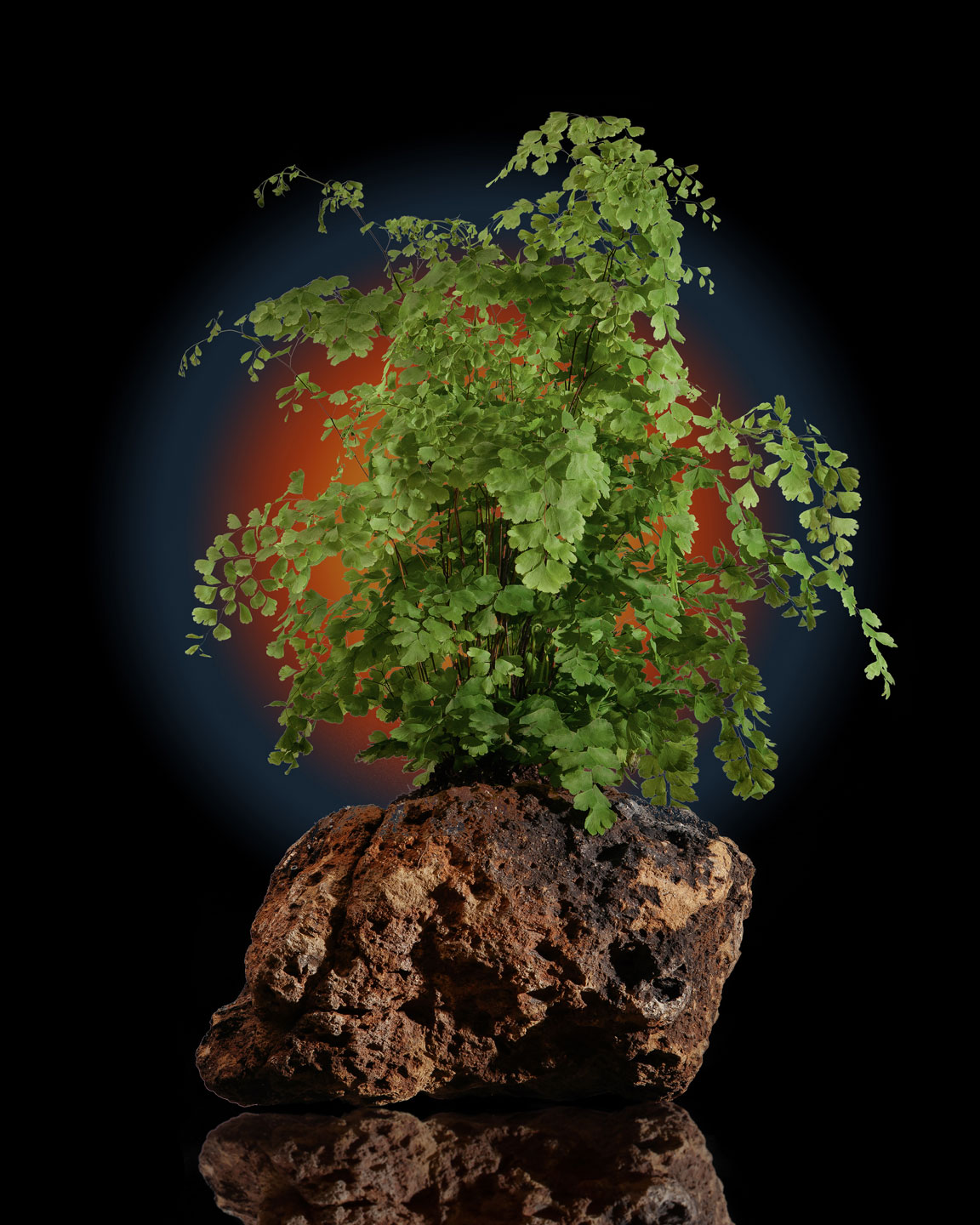

In ROOTS, I included some of my photos of a Canna indica, Joshua tree, maidenhair fern, Tofu salad, ikebana, and a family selfie in front of a giant flower sculpture. They were taken right before and during the global pandemic, and were included in my photo journal do not go gentle into that good night. They prove I exist and see things; that I’m alive.

Do you remember the first time you ever grew something?

I remember when I was a child, I loved to steal garlic from the kitchen and use my fingers to pinch holes in a pile of dirt, put the garlic in, and see them grow. It was like magic, I was obsessed with it.

What does decolonising horticulture mean to you?

Decolonising horticulture means a lot to me. For one aspect, it’s like a diaspora: we are the seed, like dandelions, or a spiky seed hanging on an animal, or seeds in birds’ poop. We were passively immigrating. However, with humans involved, seeds can be invasive and harmful. So, to decolonise is to respect the native; to create a healthy and safe environment for all kinds of beings in the community. Also, as we all know, more diversity in nature always means more stability when facing disasters. When we are taking care of plants, we are taking care of ourselves. It works the same way. We should be more inspired by the plants, and learn from them.

Do you have any advice for people wanting to work on decolonising horticulture and indeed nature at large?

Try to sit down and talk to your plants. Say 10 good words to them everyday. It’s a fun thing to do. I learned it from the Korean drama Crash Landing On You.

When have you felt most connected to nature?

When I was in the village where I grew up, picking wax berries from the trees my grandpa planted decades ago. And then it rained all of a sudden, and you could smell petrichor. It was the best time in my life.

Akshay Mahajan, 35, Goa

Tell us a bit about yourself.

I’m a photographer who lives in a wilderness of their own making. One has achieved so little that I thought it best not to measure accomplishments in words and instead leave it to the reader’s beautiful imagination.

Can you talk us through your contribution to ROOTS?

Love, I guess is the short answer. The slightly more obtuse answer would be that I followed the folk songs my lover sings (when she thinks no one is listening) in the obscure tongue of her motherland. In one popular ballad, a woman named Behula accompanies the corpse of her dead husband, Lakshmindara, on a raft down the (river) Brahmaputra. The raft passes several hamlets while the corpse swells and putrefies. Onlookers assume that Behula is mad, but she cannot be dissuaded. “Either I shall die with him or he will come to life and I shall be beside him when he does,” she declares. Behula prays to Manasa — the goddess of snakes — who, the story goes, ensures that the raft survives whirlpools and crocodile attacks. Behula’s perseverance is rewarded when Manasa brings Lakshmindara back to life.

All of the unrecorded histories of the colonised have been passed on as myths, legends and songs from one generation to another. Stories that form the bedrock of identity; a lens through which one sees themselves. I travelled to this corner of Assam (India), where the Brahmaputra bends. I took in these poems and myths, its wandering minstrels’ ballads — about folk gods and goddesses, majhis or boatmen, hostis or elephants, flirting, longing and love, bonded labour, hunger, exploitation and the banality of existence. Using local songs as a map, I attempted to sculpt tableaux for these complex amorphous identities.

Do you remember your very first experience of growing something?

As a child, we lived in a pigeon-hole of an apartment in Bombay, our lives piled on top of each other in that beautifully misunderstood city by the sea. The small 6ft by 3ft balcony was mother’s little green jewel, overflowing with plants in every conceivable nook and cranny. I used to help her make bottle gardens in old apothecary jars. Building them layer by layer, of charcoal, gravel, and moss. Plants like Asplenium nidus, a bird’s nest fern that thrives with a plain old philodendron (one of those plants nobody can kill), planted with long sticks, adequately watered once and sealed off for eternity. A closed little glass world within a world, a completely self-sufficient piece of nature. How it would mist every morning in the semi-tropical sunshine, the entire system almost dying out to fuzzy white fungus one monsoon only to spring back to life by winter. I have one of them with me now, it’s almost as old as me.

What does decolonising horticulture mean to you?

Let me use the river as one of the metaphors, let me wield it as such for nature: when the first rains fell, the earth awakened. Where rivers wandered, life could flourish. They shaped us as a species and we worshipped them as gods. Today, there is scarcely a river unspanned, undammed or undiverted. The sheer scale of the human project has overwhelmed our rivers, just as they have done most of nature itself. Our gods have become of our subjects. Rivers give us so much more than water: they have flowed to our lives as surely as they have flowed through places. But as we have harnessed their power, we have forgotten to revere them. This reverence is at the root of decolonising horticulture, removing the human fallacy of control from an unfathomable system.

Do you have any advice for people wanting to work on decolonising horticulture and indeed nature at large?

Sadly, a subaltern people can still never express ways of knowing, and, instead, must conform to the colonial ways of knowing the world. Most knowledge of nature, and indeed horticulture, come from the practices of this overlooked global majority. Any work that looks at decolonising horticulture, and nature at large, in my opinion should be built in concert with these voices.

What’s the most connected to nature you’ve ever felt?

I came close to drowning on a couple of instances. In that moment, I thought it was going to consume me, it let me go. It was both terrifying and exhilarating at the same time.

Annie Mackinnon, 26, London

Tell us a bit about yourself.

I’m Annie and I work across design, arts and music. The main focus of my work is looking at how metaphors, language and code shape interrelations and thinking between technologies and ecologies.

Can you talk us through your contribution to ROOTS?

At ROOTS, I am exhibiting a sculpture and a painting that are part of a body of work called ‘Subliming Skying, Star Gazing, Screen Glazing‘. The work revolves around the theme of chaos: its emergence within Chinese mythologies, contemporary ecological destruction, and entropic narratives that fuel techno-futurism. Two central motifs that appear are Xiangliu, the nine-headed snake who devastated ecology everywhere it went; and the faceless Hundun that is said to represent a primordial chaos. In Chinese mythology, Shu the God of the Southern Sea and Hu the God of the Northern Sea opened Hundun’s eyes, ears, nostrils and mouth day by day, until chaos died and the world was born.

In times when computerised systems form the basis of both connection and disconnection, these works return to ancient theories of Ganying (correlative resonance) and Qi energy as world views which depicted the natural world as an interconnected cosmos, where humans watched nature and the stars for signs and orientation.

Do you remember your very first experience of growing something?

When I was about five or six we learnt how to start growing mung beans in wet tissue and I was very into repeating this at home for several weeks.

What does decolonising horticulture mean to you?

Decolonising horticulture intersects with so many areas of necessary action in the climate crisis — from food justice to combating exploitative supply chains. It is important to be critical and make clear that colonial histories have played a huge role in environmental destruction as well as producing damaging narratives that hinder our understanding of nature, such as the Eurocentric binary separation of human/nature.

Got any advice for those keen to work on decolonising horticulture and nature at large?

Supporting and amplifying people and organisations that are working to make horticulture and land more accessible to underrepresented communities is one way to begin navigating these areas, but there is so much work to be done.

What’s the most connected to nature you’ve ever felt?

Every time I’ve swam in the sea or ocean!

Suren Seneviratne, 35 and Jatinder Singh Durhailay, 33, London

Tell us a bit about yourselves.

Suren: Hi, I am Suren. I was born in Sri Lanka, raised in South London. I’m an experimental musician and digital artist.

Jatinder: I am Jatinder Singh Durhailay, born and raised in London. I am a painter, composer and musician. We are both Petit Oiseau.

Can you talk us through your contribution to ROOTS?

Suren: I’ve composed a site-specific sound world to accompany the safe space garden that takes centre stage at the ROOTS exhibition, blending field recordings from various natural environs from around the world into one harmonious whole. During the Covid-19 pandemic, Londoners were yearning for a vital (re)connection to nature, so I wanted to help bring a little piece of the outside indoors.

Do you remember your very first experience of growing something?

Jatinder: My first experience of growing a plant in adulthood was quite specific. I chose to grow wheatgrass as I was interested in its benefits; my older brother had bought me organic wheatgrass seeds. I reused a plastic tray and tended to them with love and care; I would later add it to my juices when they were ready.

What does decolonising horticulture mean to you?

Petit Oiseau: We have to remember that horticulture and personal gardening is a form of colonising the land. We regularly discuss this with Johanna Tagada Hoffbeck (Jattinder’s wife and the editor of the Petit Oiseau publication) through Poetic Pastel as we are to launch a drawing and gardening project.

Do you have any advice for people wanting to work on decolonising horticulture, and indeed nature at large?

Our advice would be to give space for native plants and living creatures in one’s garden.

What’s the most connected to nature you’ve ever felt?

Jatinder: Nature is a part of us; we are a part of nature. We have reduced our connection as city dwellers with plants and animals, and I see, as others do, nature as a whole, an ecosystem we are a part of and responsible for in some ways. I believe we can connect ourselves every day to nature, and I think that spaces holding plants give us a sense of serenity and belonging. I love forests; growing up near Epping Forest, I always enjoyed a chance to enter a vast area full of many trees, mushrooms, animals, sounds and plants.

Suren: It’s been in my hometown of Kandy, Sri Lanka which is blessed with dense rainforest teeming with luscious flora in all shades of green. Growing up, I was surrounded by countless pet birds, fish and dogs; so my earliest and most vivid memories of nature are these. Spending time here is when I feel most connected to nature.

Sami Kimberley, 31, London

Tell us a bit about yourself.

I’m Sami, a multidisciplinary creative of British, Irish, and Chinese heritage. I’m one of the founding three Baesianz. My creative work is all about storytelling, and at this particular moment very focused on self-exploration and reconnection.

Can you talk us through your contribution to ROOTS?

For ROOTS, I decided to finally release a photo series from 2019, which I’d been holding close to my heart. It’s a visual diary called Gado-Gado capturing a trip around southeast Asia with one of my closest friends — we both had individual reasons for needing it, but ultimately it was a trip to heal. I had grown to feel lost and claustrophobic in my life and was finding it hard to connect to anything. I needed that space for clarity, to connect with my Asian roots, to focus and grow.

The photo series documents the beautiful moments in nature which in turn made me rekindle my relationship with the world around me. The name, Gado-Gado, comes from an endearing nickname given to us by locals in Indonesia in reference to our mixed-race heritage as it is the name of a mixed vegetable dish. Each image was captured with the aim of centring nature and her magic; paying homage to the places that healed me and showing nature as the star.

Do you remember your very first experience of growing something?

I am very lucky to have grown up in Cornwall, so I didn’t really grow anything as a child because I was surrounded by so much nature. I loved to just explore the coast and woodlands around me. It wasn’t until I moved to London after university that I really grew anything, and I did the classic thing of buying a bonsai tree from IKEA. I remember how it lost all its leaves at the same time as I went through a break up and I loved watching it regrow, it was very therapeutic.

What does decolonising horticulture mean to you?

I think humans, particularly in cities and in the west, have lost touch with nature and the space between us has gotten bigger and bigger — from how we get our food, to how we interact with the plant life around us. Lately I’ve been reading a book called Lo-TEK, where the writer (architect Julia Watson) talks about using indigenous building materials and techniques in contemporary urban living, so as to create a more sustainable future. There is so much knowledge and craft which has been lost, overlooked or ignored; and now more than ever it’s crucial that we find ways to work with the planet we live on rather than consistently taking from it.

Do you have any advice for people wanting to work on decolonising horticulture, and indeed nature at large?

To get started, my advice would be to follow Grubber Community, get out into nature as much as possible, propagate your friends’ plants and fill your house with life!

What’s the most connected to nature you’ve ever felt?

The trip which Gado-Gado documents is definitely the most connected I’ve felt. But more generally it’s whenever I’m on a boat on the ocean. There’s something about the water that makes me feel so calm, a sort of peace I don’t get elsewhere. I think that its vastness, strength and unpredictability make me completely powerless; in those moments I stop worrying about life and just take it all in.

See ROOTS at London’s Art Hub Gallery in Deptford between 20-22 August, then follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more art.