This article originally appeared in i-D’s The Acting Up Issue, no. 349, Fall 2017.

In the downtown Los Angeles studio of the anonymous designer 69, there’s a small replica of the white, turreted house from the 80s movie Beetlejuice, encased in plexiglass and elevated on a white stand like a Jeff Koons basketball. The model is weird and idiosyncratic, yet somehow perfect and universal.

That sense of paradox is written right into the 69 manifesto. “69 is timeless and classic yet made in our present and meant for the future,” the brand’s website declares. Which, not coincidentally, is sparklingly gorgeous and intuitive. It could only have been designed by a millennial, and yet the first model you see in the e-commerce section is an older woman with long flowing grey hair.

In an apt mirror of our times, the concept of identity (or anti-identity) is a key part of the 69 story. The designer insists on beyond Margiela-level obscurity, and is equally insistent that the brand is “non-demographic” and “for everybody”.

By appealing to everybody, 69 aims to cast its (denim, oversized) net extremely wide. “It’s not meant to be a fashion brand,” the designer says. “It’s meant to be a lifestyle brand and it’s supposed to be comfortable and durable and timeless and classic.” They make dog clothes and kid’s clothes and gender-neutral adult clothes for now, but what they really want to do is make furniture and creative direct an entire hotel.

Or better yet, a television show. The ghost of the hit 90s proto-reality programme The Real World is everywhere in the brand’s universe. A neon version of its scrawled logo presides over a giant chambray couch in the designer’s live/work studio. And echoes of its pioneering, Benetton-diverse, positive/edgy casting float through 69’s branding, from the happy dancers in its videos to the motley crew that populates its website. The designer dreams of making their own version someday, which would be close to the original, “but it would be structured in the way that would just deal with relevant topics. It’s gonna happen.”

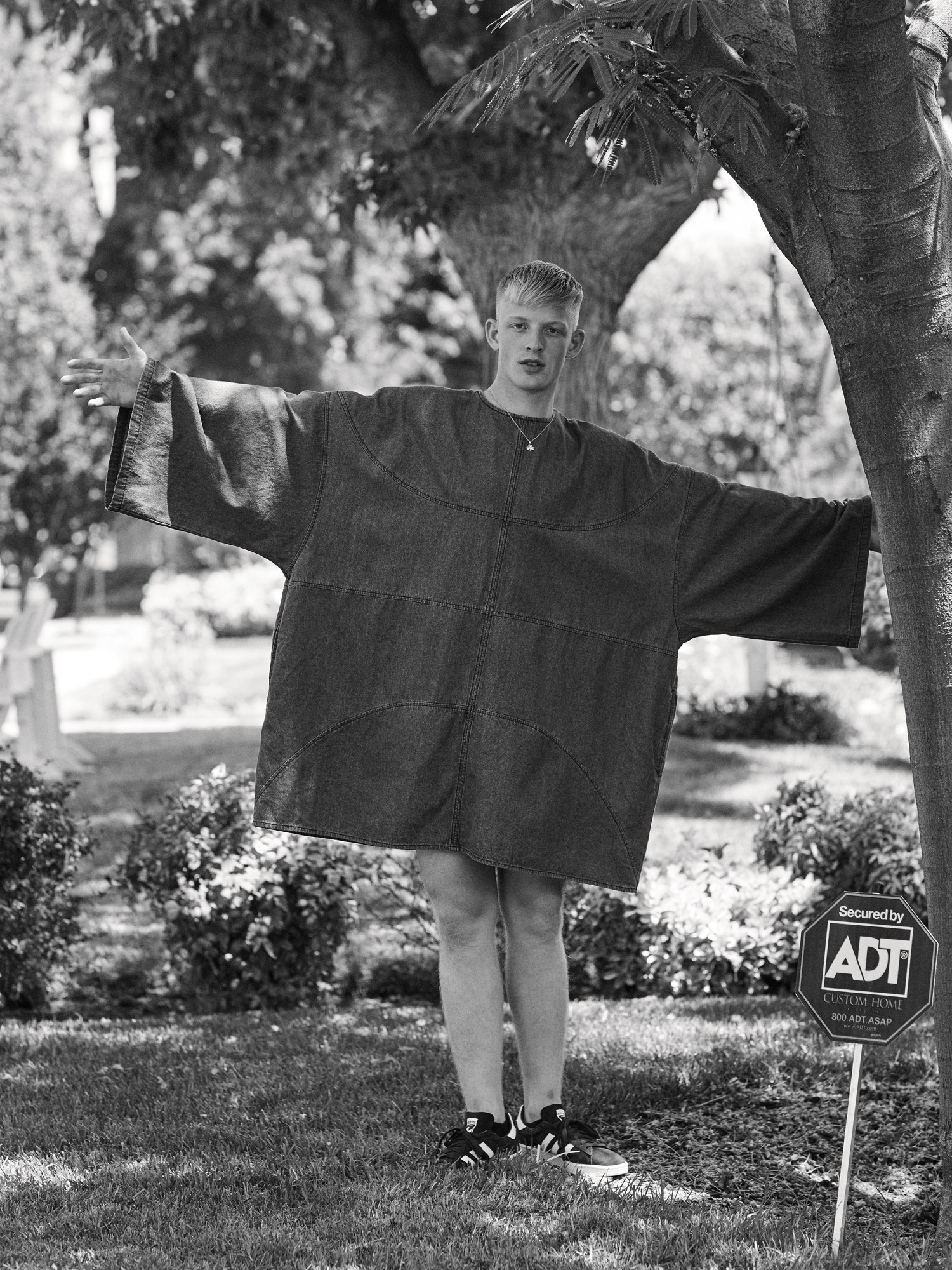

But for now, clothing, because “it’s the most easily accessible thing.” Since its launch in 2011 (with a collection called Summer of 69 ’12), the brand has gained a cult following for its modern, conceptual angle on basics, with a concentration on cottons and denims. “The brand is really known for being very structural and architectural, but you can move really well in it,” the designer says. “People really like the oversized shit.”

Clothing like the “Everyday Dress” and the “Cocoon Dress” have clearly absorbed Yohji Yamamoto’s pattern-making. But there’s some 90s Tommy Hilfiger in the denim sportiness, and undeniable Maria Cornejo artsy-mum vibes too. The connection to Margiela’s high-concept wearability is apparent (“I think that we’re two peas in a pod,” the designer says). For autumn/winter 17, Buffalo plaid gingham is playfully fashioned into jumpsuits and culottes. And the brand recently came out with T-shirts to support endangered coral and bee species.

At a time when many brands and stores are questioning gender distinctions, a unisex approach is an authentic part of 69. “I just roll my eyes at those buzzwords because I’ve always just called it non-demographic. It wasn’t a decision, it was a reflex.”

Despite its un-Google-able name, 69 is extremely concerned with branding. The distinctive 69 symbology is quite present in its social media, and on oversized tote bags. In the post-Acne fashion landscape, sometimes an unorthodox name can be the most memorable. When asked what advice they have for the next generation, the designer says, “It’s really all about branding and marketing, like, you could sell a turd, if you wanted to.”

Of course, a big part of 69’s branding is its facelessness. “The whole ethos of 69 is that it’s for everybody, and by it being anonymous, it gives it that mystery that I think is way more interesting than a personality.” They don’t want their personal story publicised, or even their gender. “As a society we like to build people up and bring them down”, they muse.

Marketing and design aside, one of the most creative elements of 69 is the way it’s disrupting the fashion system. Sizes are combined into X/Small, Medium/Large, and one-size-fits-all. The approach to seasons is loose. And rather than leaning on a costly wholesale process, the brand sells directly to consumers whenever possible, through its e-commerce site, LA studio sales and, most unexpectedly, on eBay. The clothing is manufactured in LA, “a hop, skip, and a drive away,” from the design studio.

Trainers Adidas.

Walking through racks of chambray clothing arranged around custom-made chambray furniture at 69’s studio, one wonders if the designer ever feels restricted by the rules they’ve created. Do they wish sometimes they could make something completely ornamental? Yes, they say, and it would work in the right context. They’re into exploring big collaborations, the type of thing no one would ever expect of them. The Met Ball, for example. “If we had opportunities to do, like, red carpet shit, I could bust it out.”

Every lifestyle brand, even the most humble one, is aspirational. “It is sort of like a fantasy,” the designer states. “If I were to do a Real World, everyone would be wearing 69, and living in this 69 household.” The designer’s dog, clad in custom 69, stretches out on a 69 pillow, and for a moment in time it all feels very real and like the best idea ever.

Trainers Adidas.

Credits

Text Rory Satran

Photography Bruno Staub

Styling Julian Ganio

Hair Ramsell Martinez at Lowe & Co. using R + Co. Make-up Kali at Forward Artists using M.A.C Cosmetics Digital technician Morgan Acaldo. Styling assistance John Handford and Taylor Erickson. Production Rosco Production. Casting director Barbara Pfister. Casting assistance Sam Chow. Models Isabella Sprague at Vision.Ryan Rice and Egypt Craft at Wrenn. Chloe Brill at Photogenics. Marcel Brodeur at LA Models. Isabella Sprague at Vision. Steve Hansen at D2. Beau Bielski. Special thanks Daryl McCullough.

All models wear clothing 69US