This story originally appeared in i-D’s The Timeless Issue, no. 371, Spring 2023. Order your copy here.

‘Queer fashion’ is a term that, over the past three or four years, has become a fixture of contemporary fashion discourse. Its increased prevalence correlates to a wider sociocultural embrace of queerness and explicitly queer-coded aesthetic expression – see the mainstream popularity of celebrities like Lil Nas X and Troye Sivan, alongside brands like Alled-Martinez and Ludovic de Saint Sernin, as cases in point.

However, while the clothes widely categorised as ‘queer fashion’ almost invariably transgress conventional, heteronormative sartorial mores, the sensibility that the term has come to designate is pretty fixed: a hyper-sexed, femme-inflected aesthetic designed for slim-to-athletic male bodies. Consequently much of the ‘queer fashion’ we see today predicates more on sexual identity and expression than it does on what the late bell hooks famously described as “queer-pas-gay” – or “queer-not-gay”: an understanding of queerness as “being about the self that is at odds with everything around it and that has to invent and create and find a place to speak and to thrive and to live.” Queerness as perpetual self-invention, rather than a fixed state.

Read in this light, the fashion created by A–Company, the New York-based label founded by designer Sara Lopez in 2018, is as queer as it gets. Though she doesn’t necessarily label her work with the term, this conceptually broad, liquid understanding of queerness permeates her practice. Marked by a clean, deconstructed elegance, relatively everyday garments – office uniforms, trench coats, evening dresses – are artfully tweaked, inverted and reimagined in ways that elevate them beyond the normative contexts in which they’d typically be perceived. It would, for example, take a pretty bold City Boy to turn up to the office in the dramatically cropped pinstripe wool trousers with an intentionally scruffy fold-over waistband that featured in A –Company’s SS23 collection. Elsewhere, a squarish candy-cotton- coloured jacket is constructed inside-out, the exposed pocket linings creating a pearlescent patchwork, and a bias-cut column gown reveals itself to be made up of countless men’s ties.

When Sara shares a few of her perennial sources of inspiration – the works

of artists, scholars and writers like Zoe Leonard, Félix González-Torres, Derek Jarman and Etel Adnan – immediate parallels present themselves; namely, a shared interest in picking at the seams of ‘the ordinary’ to reveal plurality and possibility beyond. It’s an expansive perspective that defines Sara as a designer, sure, but as a person, too. Growing up in Texas in a liberal family, she found herself drawn to the expressive potential of clothing long before she became aware of ‘fashion’.

“I was always decorating myself and dressing up in all of these different ways, adding paint or different objects I would find to my clothes,” she says, describing the impulses that later compelled her to pursue a creative career as she grew older. A deeply conceptual thinker, she initially planned to pursue visual arts, but changed tack to fashion design upon realising “that clothing has this deep access point that the visual arts don’t.”

In 2012, after studying at the University of Minneapolis, with a stint in Paris under the tutelage of an alumnus of the off-kilter couturière Anne Valérie Hash, Sara moved to New York. There she spent a formative four years working for Rachel Antonoff – the designer beloved by early 2010s downtown It Girls Lena Dunham, Tavi Gevinson and Aubrey Plaza – delving into every nook and cranny of the independent brand. “I saw every aspect of how a brand works,” Sara recalls, “I started helping her with the design pretty immediately, and I also had a lot of access to the production side, the development, the collaborations.”

“I’m so drawn to turning things inside out and deconstruction, it’s so queer. It echoes this idea of being in this ever-becoming state.” Sara Lopez

It did, however, expose her to “the difficulties of being an emerging brand,” and in 2016, she opted to take a year’s pause from fashion, redirecting her attention towards creating sculpture and furniture. “I needed to take time away from clothing in order to re-enter it slightly differently, and allow myself to realise that things didn’t have to be done in this very specific way,” she says.

“I needed to know that I could build a business that operated the way I wanted it to, both creatively and financially.” That realisation came in 2018, when A–Company was officially founded. From the get-go, the brand wanted to do things differently; though it was less a matter of bucking the status quo as an act of punkish rebellion, and more about creating a space that existed parallel to and distinct from the norm. A clue to its ethos comes in its name, a consciously opaque moniker layered with meaning. “First, there’s a reference to the sort of anti-branding of Margiela and what he did,” she muses, free-associating her way through the connotations nested within the at-first-glance innocuous term A–Company. “There’s also a nod to collectives like Bernadette Corporation” – the 90s NYC art-fashion collective that aped corporate speak and aesthetic as part of a wider commentary on the commodification of identity – “as I also take a lot of inspiration from the uniforms of the business world. And then there’s ‘A’ as this foundational starting point in the alphabet… It gave me a lot of flexibility, there’s an intentional blurriness.”

More than a purely conceptual enterprise, though, Sara has built A–Company with the queer community she’s part of at its core. It’s an ethos that makes itself adamantly felt in the brand’s designs, the impetus being the absence of fashion that catered to her own understanding of queerness, and that of those around her. “There was a pretty big gap in the specific kinds of clothes that I was interested in,” she says. “I didn’t see much that was filtered through a queer perspective, or that truly catered to a queer femme body… unless it’s, like, 90s lesbian chic – and there’s a lot of writing on how that was capitalised on and commercialised. Queer women have often been seen as unfashionable,” Sara continues. “I’m trying to do things differently, creating clothes that my friends and I want to wear.”

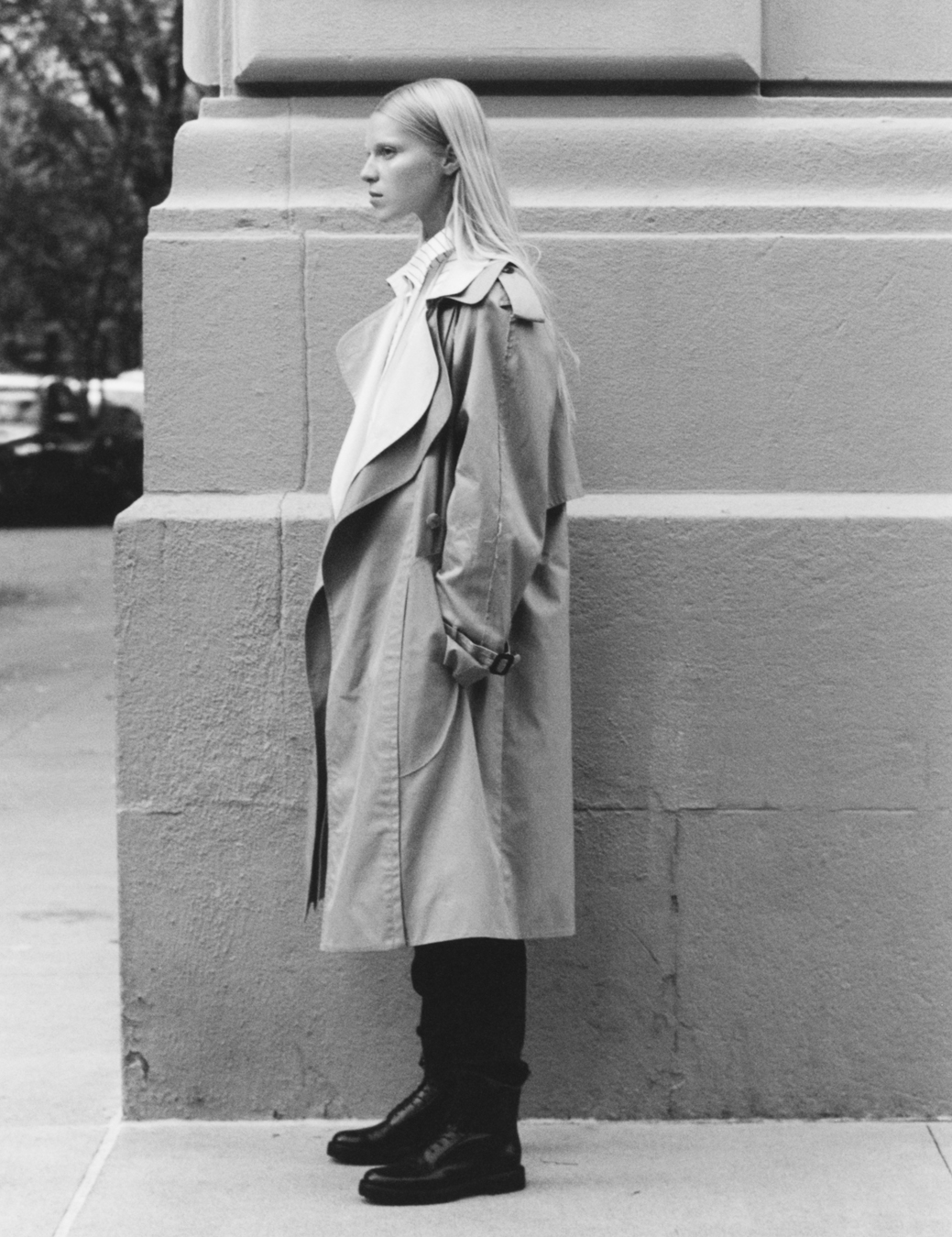

What’s perhaps most intriguing about the label’s clothes is the range of aesthetics they cover. Contrary to many examples of designers who might be described as ‘queer fashion’, it’s difficult to neatly summarise the most recent collection that A–Company presented during New York Fashion Week in September. Slim elegant tailoring served as the foundation, but then we had tank dresses in which the relative modesty of the silhouette was counterposed by the fact that they came in sheer gauze. And sure, there were vented gabardine jackets and trench coats with overblown, layered lapels, but there was also a flowing dress with a sari drape that peels down to reveal a spaghetti-strapped underlayer.

What drew the collection together, though, was a knack for taking relatively standard garments and skewing their semiotic value; queering them, essentially. “I’m always trying to twist things and understand these archetypes differently, looking in particular at gender expression and identity construction,” Sarah explains of her design process. “I think that’s why I’m so drawn to turning things inside out and deconstruction – it’s so ultimately queer. It echoes this idea of being in this ever-becoming state, there’s a constant curiosity.”

While it isn’t hard to argue that A–Company’s fashion is conceptually queer, Sara is, however, wary of her work being perceived as ‘queer fashion’. “It’s impossible to have a single response to what ‘queer fashion’ is, and, frankly, it would be so limiting to say that there is one.

One of us can’t make that designation for the whole. We all come from different places and feel our queerness differently,” she says. “All of those notions of queerness need representation and space. For me, though, ‘queer fashion’ is really about a holistic approach that starts at the very beginning of the business model. It’s about how to interact with people and all the things that are around the brand. Who I’m collaborating with, who’s on set. How we’re engaging with the community and giving back.” Ultimately, for Sara, what drives her practice forward is the aim to create a fashion brand that intentionally subverts – and defines itself against – the expected norms of how a fashion brand should be run: what could be queerer in spirit than that?

Credits

Photography Phil Engelhardt

Fashion Matt Holmes

Hair Tamara McNaughton at Bryant Artists using Bumble and bumble

Make-up Frank B at Home Agency

Photography assistance Jae Kim

Fashion assistance Emmalynne Walpole, India Reed and Farrah Wohlford

Tailor Ketch at Carol Ai Studio

Hair assistance Nastya Miliaeva

Make-up assistance Natsuka Hirabayashi

Production Family Projects

Casting director Samuel Ellis Scheinman for DMCASTING

Casting assistance Keina Koné

Models Américá Gonzalez at Supreme, Bella Berghoef at The Industry, Colin Jones at Women

All clothing A–COMPANY