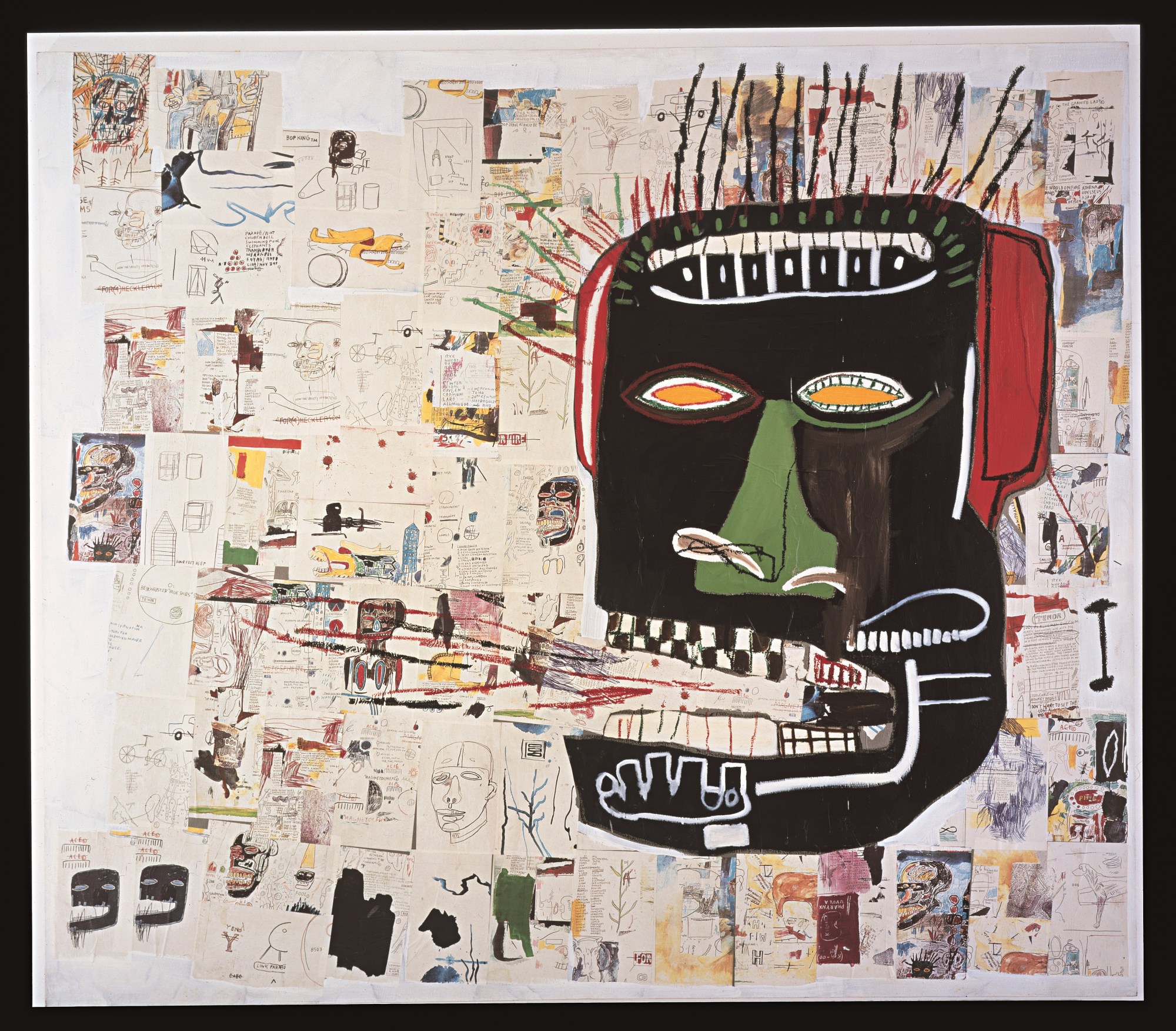

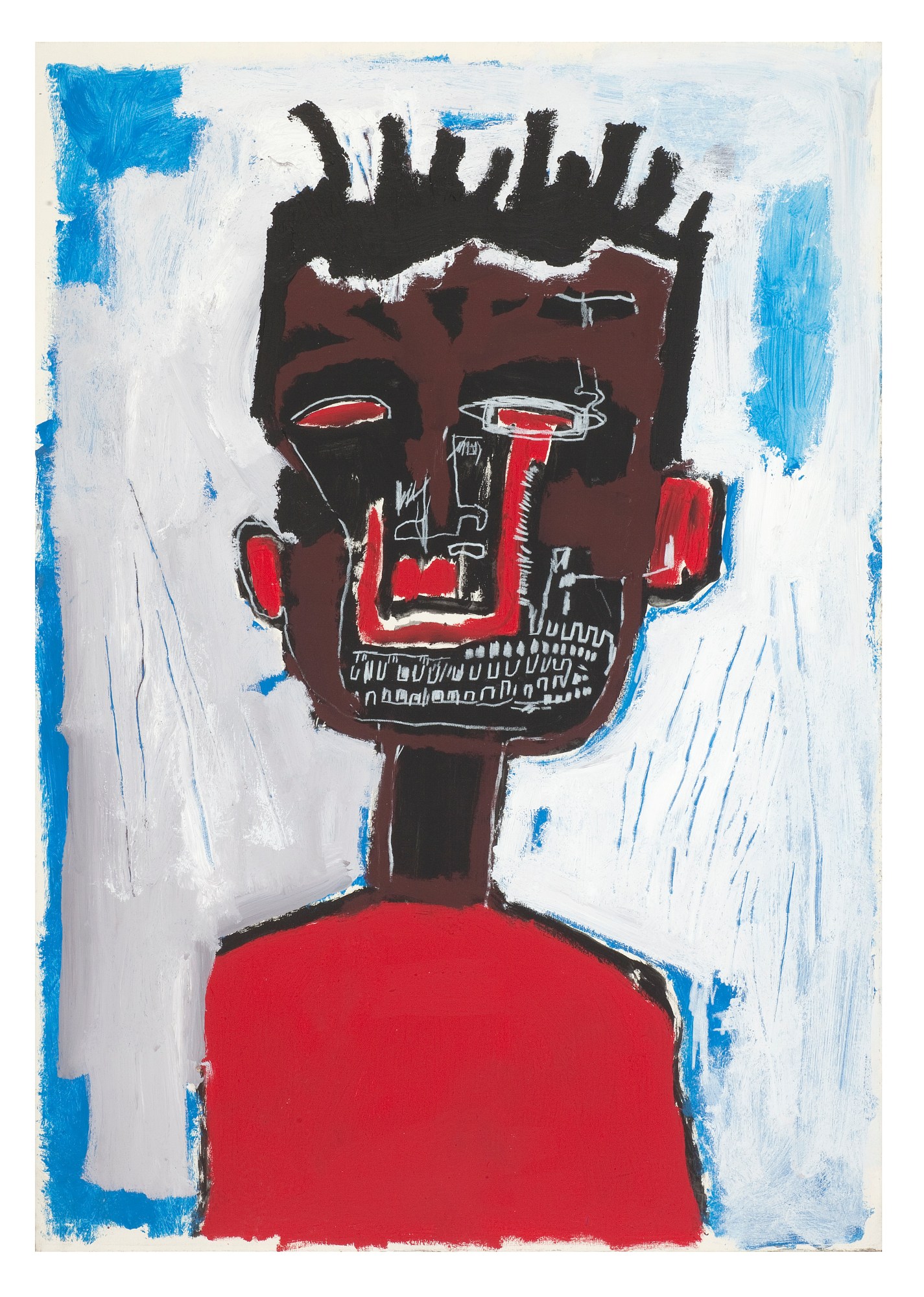

Even a cursory glance around the Barbican’s new Basquiat: Boom for Real exhibition will reveal to you the New York artist’s love of words. From the early pages of poetry torn from his notebooks to graffiti tags under the SAMO© alias, and his most famous paintings, Jean-Michel used words and phrases for comedic and symbolic effect. His intended references often appear deliberately obfuscated, but range from nods to TV and film, to Heavyweight boxers, ancient Egyptian mythology, human biology, and anti-capitalist and anti-racist sentiments. Here we’ve decoded a few of his most famous and ubiquitous words, phrases and motifs…

Boom for Real

The title of the exhibition is taken from a catchphrase of Jean-Michel’s, which can also be found in two of the paintings in the show, Jimmy Best (1981) and Untitled (Crown) (1982). “In a way it’s very enigmatic and difficult to interpret, and in a way it’s very straightforwardly understandable: it was a kind of exclamation when something really inspired him,” curator Eleanor Nairne told i-D at the launch.

SAMO© (as an end to)

In Jean-Michel’s graffiti partnership with Al Diaz, they went by the name SAMO©, a shortening of the phrase ‘Same old shit’, to ‘Same old’, and eventually just ‘SAMO’. They wrote and tagged statements all around New York, with many starting ‘SAMO© AS AN END TO …’ with endings including: THE POLICE / ALL THIS MEDIOCRE ART / MASS MINDLESSNESS / THE 9-TO-5, WENT TO COLLEGE, NOT 2-NITE HOMEY BLUES.

Three lines

At the end of the SAMO© tag, Basquiat would often spray three vertical lines, and he wrote ‘E’s in his artworks as just three horizontal lines. While there is no explicit discussion of his three line motif in the exhibition, the curators note his love of symbols, and have included two of Jean-Michel’s own books on the topic: Symbol Sourcebook by Henry Dreyfuss, and Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy by Robert Farris Thompson. In Dreyfuss, the three line motif appears as a ‘Hobo Sign’ meaning “This is not a safe place,” and in Thompson it appears as an Afro-Cuban ‘Dark Sign’ meaning “Prevent danger”.

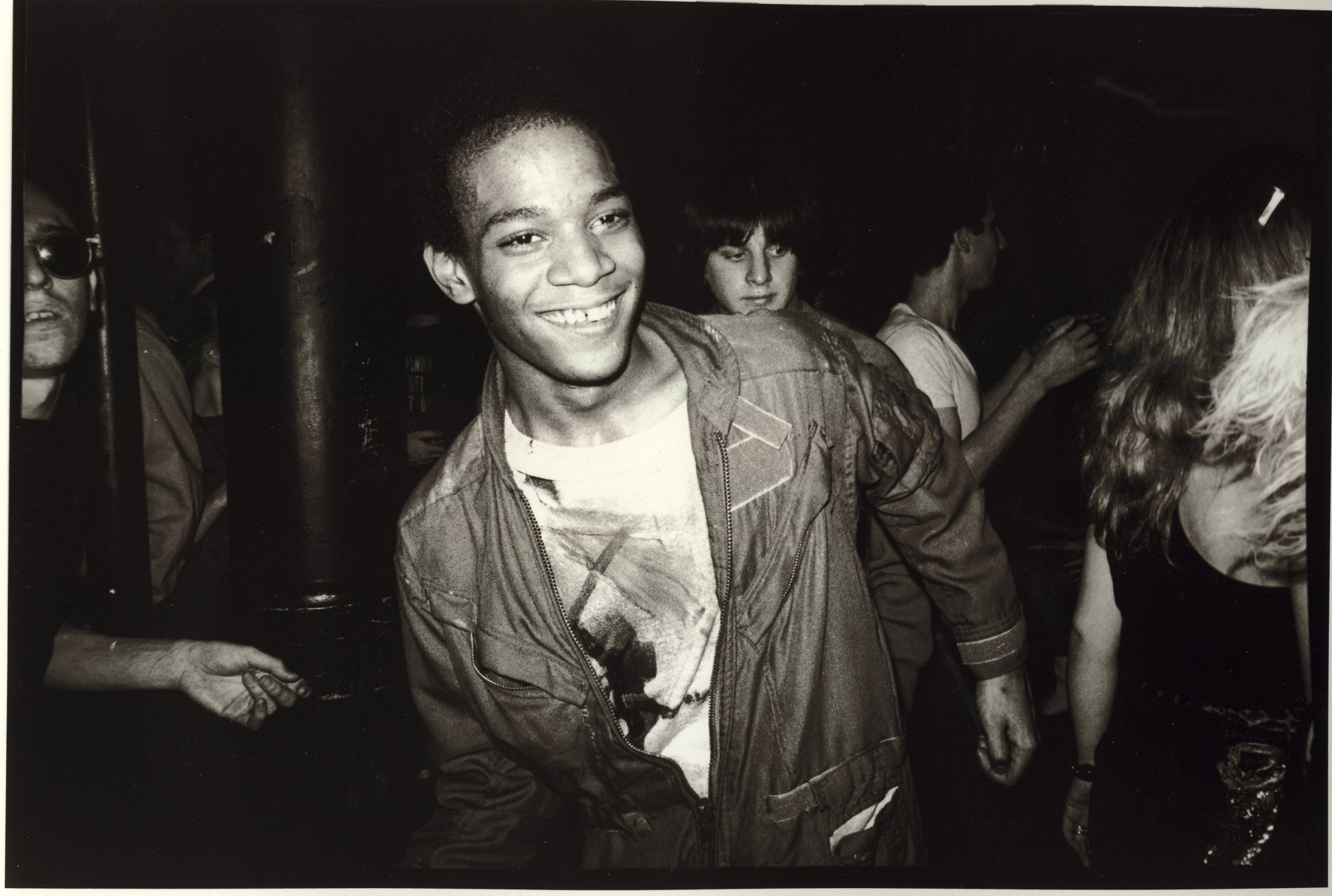

The Radiant Child

The Radiant Child is the title of art critic Rene Ricard’s famous 1981 Artforum essay, in which he considers Jean-Michel’s work alongside that of Judy Rifka, Keith Haring and a number of graffiti artists. The first major article on Basquiat, it warned the art world of the foolishness of fetishising the “idea of the unrecognized genius,” noting: “Nobody wants to miss the Van Gogh Boat.” It is also the title of a documentary made by Jean Michel’s friend Tamra Davis, which came out in 2010.

The crown

A three-peaked crown symbol appears in many of Jean-Michel’s paintings, topping the heads of people he admired and respected, including the boxer Jack Johnson and his friend Keith Haring. In The Radiant Child essay, Rene Ricard writes that he asked Jean-Michel where he got the crown. “Everybody does crowns,” Jean Michel is quoted as responding, but Rene notes: “Yet the crown sits securely on the head of Jean-Michel’s repertory so that it is of no importance where he got it bought it stole it; it’s his. He won that crown. In one painting there is even a © copyright sign with a date in impossible Roman numerals directly under the crown. We can now say he copyrighted the crown.”

Hollywood Africans, and Beat Bop

During a 1982 trip to California, Jean Michel and the rappers Toxic and Rammellzee began referring to themselves as the Hollywood Africans. The trio appear in a 1983 Basquiat painting of the same name, but with dates referring to the 1940s, a comment on the lack of opportunities in Hollywood for black actors, the Barbican curators suggest, noting that it could also be a reference to actor Hattie Daniel, the first African American to win an Oscar, in 1940, for her portrayal of Mammy, a racist caricature of a black maid in Gone With The Wind. After returning to New York, Jean Michel and Rammellzee produced a 10 minute long hip hop single called Beat Bop.

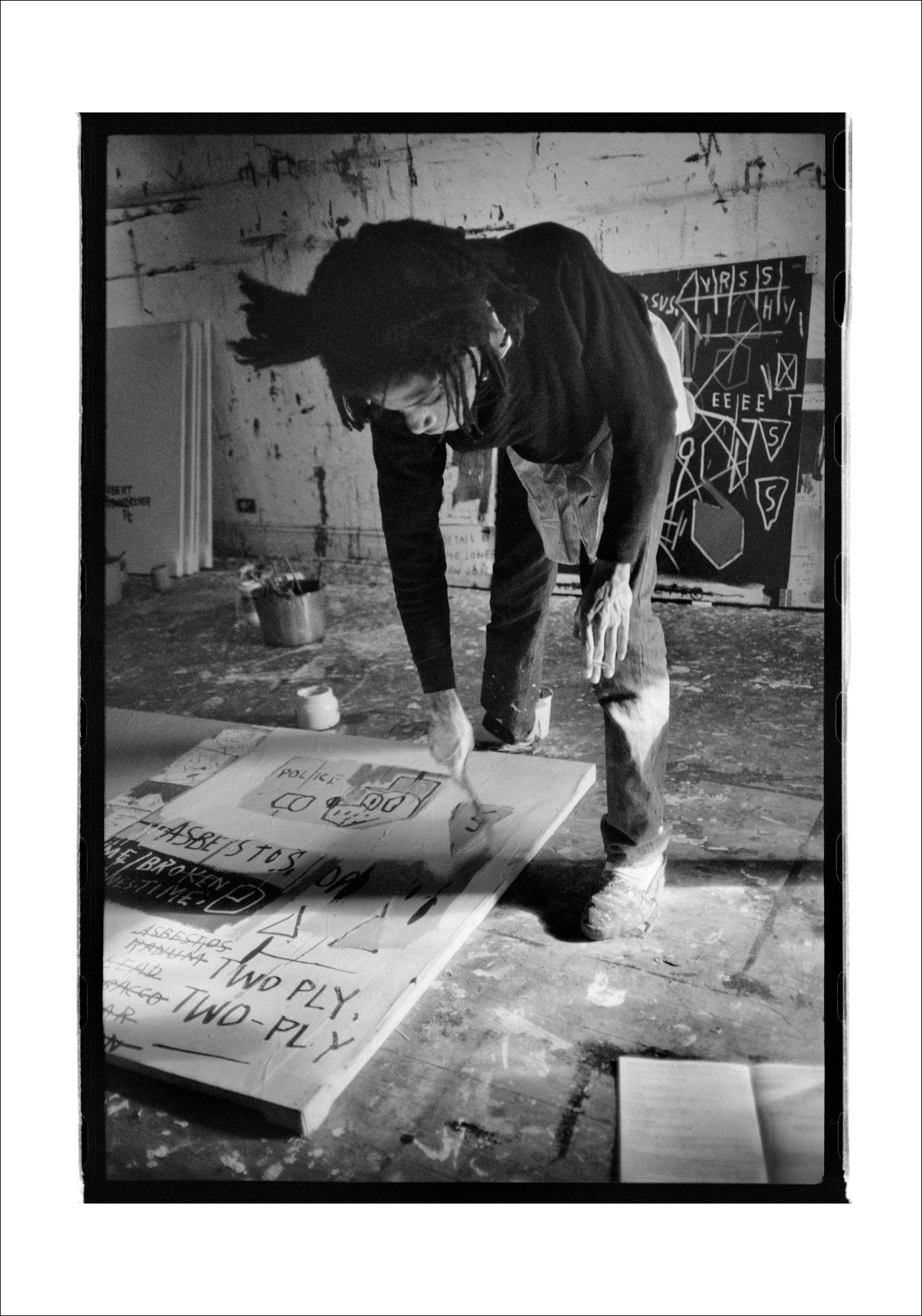

Vitaphone

“I’m usually in front of the television. I have to have some source material around me to work off,” Jean Michel explained in a 1985 British film of him at work that is quoted in the exhibition. He was inspired by TV programmes and films, and the word ‘VITAPHONE’ appears in a number of his paintings — a reference to the technology behind ‘talkies’, where sound was recorded separately, but played in sync with the film. The exhibition text explains that Basquiat became obsessed with The Jazz Singer, the first feature film to use the vitaphone technology, in which the white lead character performs in blackface.

Aaron

In a famous photo of Jean Michel, he stands in front of a canvas in a brown suit and red Adidas T-shirt, wearing an American football helmet. The helmet bares both his crown motif, and the name Aaron. The Barbican curators highlight the diversity of his references with suggestions for the identity of Aaron, noting that it “could connect to the black baseball player Hank Aaron (who beat Babe Ruth’s home run record in 1974),” adding, “But Basquiat may also have been referencing the black antihero of Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus and the brother of Moses in the Old Testament, who frees the Israelites from servitude”.

‘Plush. Safe’ He Think

“Well, I’m not going to try and interpret that for you,” laughs curator Eleanor Nairne when i-D asked about the phrase. “With some of the more cryptic early pieces of poetry, we’ve tried not to decode them too much, precisely because it’s that very ambivalence of meaning that makes them so intriguing.” You’ll just have to go and see for yourself (Boom, for real).