One of the pleasures of art season in Paris is that you aren’t reduced to spending your time in an environmentally controlled tent, with no natural light, for hours on end. Of course the pleasure of most art seasons aren’t the fairs themselves, but the wealth of extra curricular activities that happen around them; the people, the parties, institutions who roll out their best shows.

But in Paris, you’re treated to FIAC at the Grand Palais, with its spectacular glass dome and wrought iron roof, and massive stone facades; and, at Paris Internationale, FIAC’s young sister fair you can stroll through the winding corridors, grand staircases, panelled saloons and tiled servant’s quarters of a 19th century hôtel particulier, which used to house the collection (and home) of collector Calouste Gulbenkian. FIAC might do its best to obliterate its beautiful architecture, by necessity really, neutering its space into avenues of identical white cubes, but Paris Internationale played up to it.

The fair, which launched last year, is the initiative of four youthful Parisian galleries; High Art, Sultana, Crèvecoeur, and Antoine Levi; and Zurich’s Gregor Staiger. Conceived as a response to the sterility and boredom of the traditional art fair format, and a new model more tailored to an emerging generation of gallerists and the artists they represent; consequently it feels free and slightly untamed, full of charming rough edges, and is a joy of discovery and surprise.

The standard art fair unit, the white cube booth, is broken down and reinvented in the varied rooms and salons of the house on Avenue d’Iena, spitting distance in between the Arc de Triomphe and the Eiffel Tower. Aside from the five organising galleries, Britain is well represented by London’s Arcadia Missa, Carlos/Ishikawa, Project Native Informant, and Union Pacific, and Glasgow’s Koppe Astner; but beyond this there’s 61 galleries and project spaces delicately crammed into every nook of the house’s four stories.

The most successful galleries of the fair responded to the architecture of the building instead of fighting against it. Galerie Gregor Staiger was showing the work of Nicolas Party, a young-ish painter whose been steadily on the rise since graduating from Glasgow School of Art in 2009. Their booth is in the fact the space above the building’s grand staircase, and is displaying just one work (though what a work) by the painter. Nicholas creates intricate backdrops for his images to sit upon, here turning the whole of the wall, about a 15 foot square, into a trompe l’oiel of marbles in chalky whites and glistening greens, upon which sits an image, a cartoonish Whistler reimagined by a surreal Gaugin, maybe, of two people and cat.

Parisian project space Shanaynay, had turned a tight corridor in the tiled servant’s quarters in the basement into a loosely hung grouping of work by 25 artists, each display just a single work. The proximity between the wall the works hang from, and the wall you can stand by to look at it is about two feet, forcing you literally to get up close and personal with the art.

In fact the servant’s quarters, a tight maze of impossibly spiralling staircases, tiled walls, and kitchen sinks, threw up much of the fair’s most exciting works. To coincide with her solo show at Paris’ New Galerie, Arcadia Missa presented a selection of new images by Amalia Ulman, lenticulars that add a surreal twist of dark humour to the style of cartoons you might see in the pages of The New Yorker, and a selection of short video works on a monitor above a staircase.

Then just down the stairs from them was Queer Thoughts, a New York via Chicago gallery, who had the works of David Rappeneau on display. David is a young French artist whose images, scratched away in pen, ink, paint, and marker, are angsty and dystopian. He elegantly creates a rich world full of lost boys and girls who centre and anchor his aesthetic creations, they are posed often using technology, or smoking, or popping pills, dressed up in Reebok, Schott.

Aside from David and Nicolas, there were other nods towards a trend towards a new vision of figuration in painting. Jenny’s from Los Angeles had the work of Julien Ceccaldi on display, who creates manga inspired images imbued with a surreal sense of humour. They resemble animation cells pulled from sites of grander meaning, stripping characters of narrative that might existentially define them. His characters feel just as lost as David Rappeneau’s, but whereas David’s vision is bleak and desaturate, Julien’s is overloaded with colour and force to drive the surreal home.

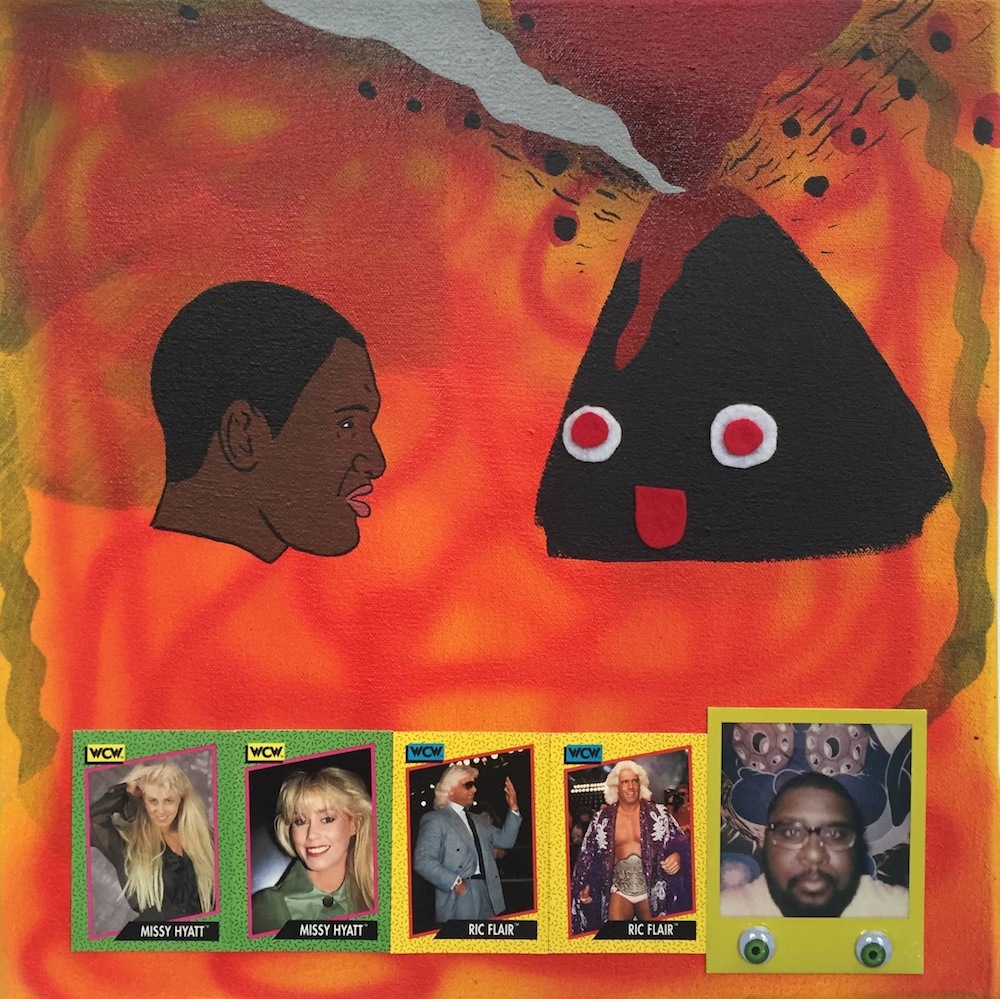

Or there was David Leggett, who was on display at Chicago gallery Shane Campbell’s booth. David uses cartoon style images, pop culture references and bright bold colours to critique big issues in American, usually race. Here he had a work that displayed a black Bart Simpson being harangued by Chief Wiggum, under the title DWB, or driving while black. Or another, that combined images of WASPy pumped up weirdos from the world of wrestling with a polaroid of the artist. David is an artist not much known beyond his native Chicago, but definitely deserves wider recognition.

One of the best things about the fair was just how much there was to discover here. Easily one of the highlights was the work of young Parisian painter Louise Sartor, who was showing at Galerie Crèvecoure. She’s mounted few exhibitions, but the gallery had sold all of her works by the end of the first day, as good an indication as any of a star on the rise. Louise’s painting combines creepiness with prettiness, delicacy with toughness. She creates small, postcard sized paintings, often on pieces of paper, and usually framed only by a small piece of broken glass that partly obscures the image. Here Louise’s works quietly dominate a large circular, pea green and gold leaf wallpapered salon on the house’s second floor. The paintings feature stolen images of women, often from behind, or captured unaware; their simplicity lends them a beauty that makes you all the more uneasy about being sucked into their world. Not content with merely being a standout painter, Louise also contributed a incredibly fun DJ set to the fair’s opening night party at Le Mano.

Not that every gallery was relentlessly pushing the new; Chateau Shatto from LA had two 70s work by Dutch artist Jacqueline de Jong in their booth, alongside French philosopher Jean Baudrillard’s landscape photography, that was hung above their booth’s fitted kitchenette. De Jong is relatively unknown despite being a member of the Situationist International in 60s France and contributing to the running of The Situationist Times newspaper, before travelling across America in the 70s by train in a kind of mobile studio; from which she captured everything she saw, condensing documentary fragments into one mad, evocative whole. Elsewhere Lea Lublin’s work was on display at Deborah Schamoni Gallery, a pioneer of art that engages with the audience in new ways in the 70s. Here there was Flor De Ducha, a towering sculptural flower, made up of pieces of coloured plexi, that also doubled up as a working shower, that can be used when installed, and was originally conceived a piece of public art and installed in a park in Colombia.

But there was much to chance upon; Lambdalambdalambda from Kosovo, What Pipeline from Detroit, and Dawid Radziszewski from Warsaw, all provided windows into their local scenes. Or Galeria Augustina Ferreyra, from Puerto Rico, who were showing works by Ad Minolti, an Argentine painter who uses geometry and colour to break down figurative language into something trans-humanist and freeing, reimagining the human space of Le Corbusier as something beyond an archetype of whiteness and maleness. Alongside her paintings, were some tiny little box sculptures, imagined as homes for Puerto Rico’s collection of stray cats, which were the cutest works in the fair.

Closer to home, London’s Carlos/Ishikawa had the sculptural works of Stuart Middleton on display, haunting little maquettes of empty rooms the artist has lived or worked in or had some association with, tucked away on the top floor of the house. They were Louise Bourgeois-esque, in their mix of freedom and enclosure. And Project Native Informant were showing work by artist-architectural collective Ayr alongside a video piece by Georgie Nettell and Morag Keil, The Fascism of Everyday Life, that sends up the aspirationalism of home improvement type TV shows, by giving you a guided tour through the artists’ South London house, complete with dirty washing in the sink.

In fact such was the artistic success of the fair, that often you felt like you were witnessing a hugely important new generation of artists emerging. No chance of grouping it all into one movement or style mind you; but there was intimacy, openness, experimentation, and honesty on display everywhere you looked. In fact one of the reason’s this review is so late is partly because of that openness, somehow finding myself working at a booth for two days (the other being I somehow managed to delete everything I’d written about the whole week in a hungover stupor after one of the many parties). I didn’t sell anything mind. Which I’m blaming on all the talk of the market for emerging artists slowing down this year, something not helped in Paris by a week separating Frieze from FIAC, and the terrorist attacks in the city last year that have made many American collectors hesitant about travelling. It’s a shame, as the work on display points to a bright future.

Credits

Text Felix Petty