Didier William’s newest series of wood-panel works is told from the perspective of his childhood self, with all the wonder, curiosity and magic that comes with being a kid. Some of the works speak to the experiences of his parents, as they raised young Didier in Miami, Florida. While, for some, Miami can feel like a sort of second Haiti, for Didier and his family, being in the United States brought instability and a constant sense of othering.

Recently, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Miami (MOCA) presented a survey of Didier’s earlier works — the artist’s largest solo presentation yet. Now, just a few months later, he is presenting a solo exhibition of new works at the James Fuentes Gallery space in Los Angeles, titled Things Like This Don’t Happen Here — the ‘here’ a reference to Miami. “This new world was weird and spectacular and strange, partly because we weren’t from here,” Didier said. “Because we didn’t have the benefit of ground underneath us, the stakes felt that much higher.”

We sat down with Didier to talk about the show, the childhood memories that inspired the work and the ancestral connections he hopes to tap into on his journey of experiencing the world as a new parent.

How does it feel to have a solo at a gallery space again, after your career-defining show at MOCA?

It feels phenomenal to be here. This is the most personal work that I’ve made in a long time, and it’s also the most mythological work that I’ve made in a long time. The MOCA show was an encapsulated survey of my earlier career. It feels really great to come out of that show with a new direction and introduce that new direction in a whole new space. It all feels pretty euphoric, honestly.

You have so many caves and subterranean elements in this show. How do these elements play in how you think about memories and space?

Space often provides groundedness and stability. When thinking about how these moments live in my memory, I wanted to strip any stable ground away from them, because that’s how we lived these events. That’s how we experienced them: with the kind of urgency that didn’t give us the security of being from the area or being native-born citizens — an urgency that quite literally stripped the ground from underneath us. So, I like to think: how can I make images in the absence of gravity? What are the spatial conditions where we can suspend gravity? For me, that happens underwater and in air. So, in my work, you’ll see people suspended and in air, or underwater. They’re intentionally upended.

I love the piece in the show “Cursed Grounds” because it represents a compositional style you work with a lot, which is dividing the space between a subterranean world and the world above ground.

This goes back to the idea of multiple histories happening simultaneously. My partner and I are new parents, and this landscape was inspired by Lorimer Park, where we would take our daughter during COVID. When we went there, we would marvel at these beautiful, huge trees spread across the park. As I was coming back to this part of my practise about subterranean life, I wanted to think about these energetic waves as the connective tissue between us, the heavens and the ancestors. These energetic waves stitch and seam the terrestrial and ancestral worlds together.

You seem to strip away gender presentations. Have your figures always been this amorphous and anonymous?

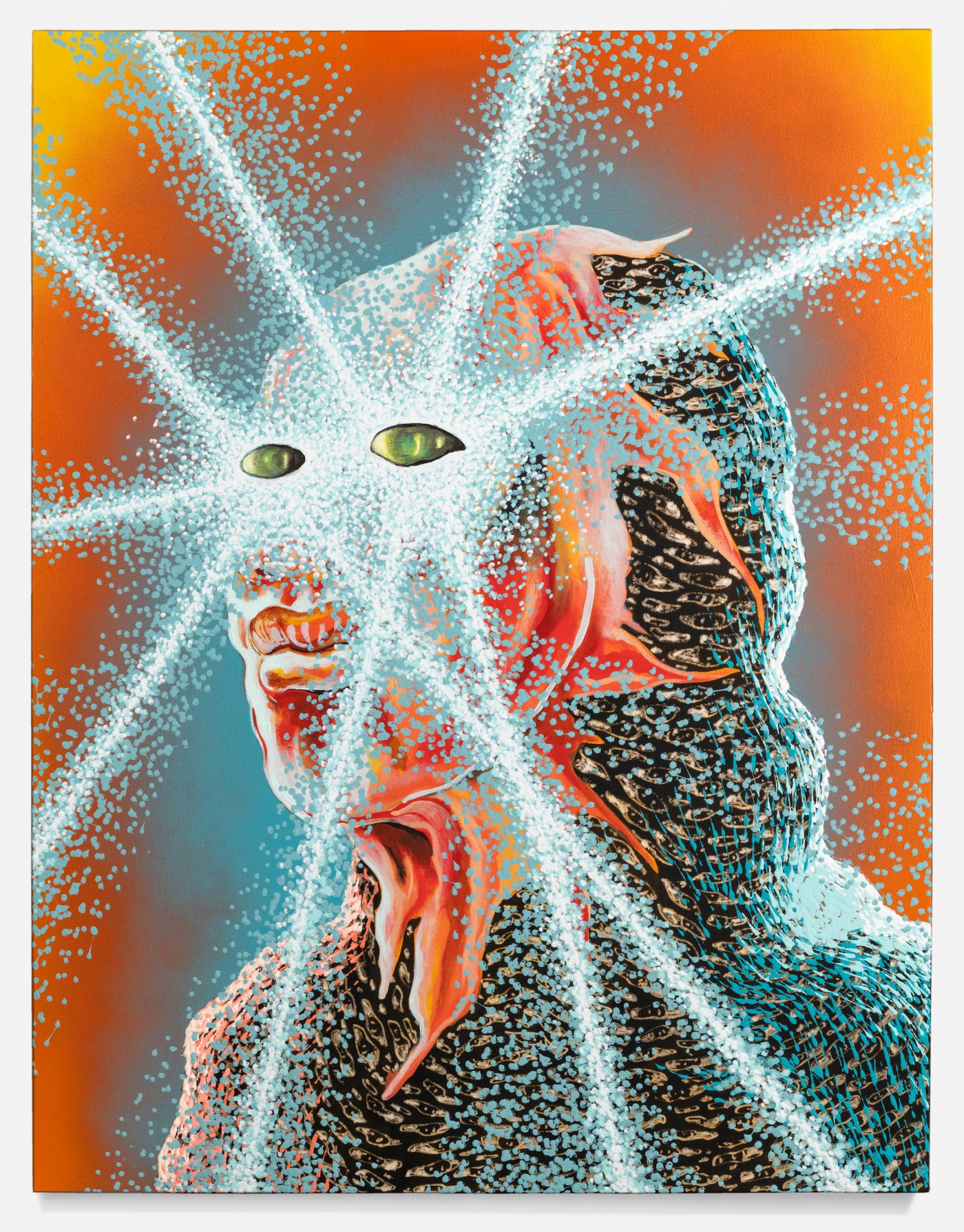

Yes, I intentionally strip them of any kind of gender formations. As a queer person, I want to think about how gender shows up in the work beyond sexuality, beyond body-to-body coupling. I want to think about how gender shows up in the family or how gender — or the absence thereof — can manipulate a space. There is a kind of multiplicity that undergirds everything about queerness that, for me, has to go well beyond the body. In the beginning, I wanted to cloak my figures in this armour of eyes. Actually, in the newer works that I am working on right now in the studio, they are beginning to shed this skin, and are beginning to “talk back” to the eyes. But rather than these figures being amorphous, I want to see them as intentionally cloaked in this shield of armour. The cloak is “anonymity” to the extent that it can be radical liberation. If you immigrate to this country speaking a language other than English, for example, you have this sort of superpower. Just as others can render you invisible, you can render yourself invisible and move through spaces with a kind of subversive energy.

There is so much power in your work, “I Wanted Her to Kill Him, I Know Why She Didn’t”. Can you tell me about the memories that brought about this piece?

When I was around eleven, my mom used to work at this Haitian restaurant in Miami and her boss was terribly abusive. There were times that he tried to sexually assault my mom. One time, my father and I went to pick her up late at night and she got into the car crying. She started telling my father how nasty this man was, and I remember being in the back seat thinking: my dad is this big strong man, and my mom is the strongest person I know. How can they let this happen to her? Why doesn’t my mother just eradicate him? Why doesn’t my father just kill this man? Why don’t they just get rid of him? My eleven-year-old brain tried to find the simplest solution. And I wanted to go back to that moment and think about, if I could have actualised it then, what would it have looked like?

Would you describe your work as surrealist?

I describe it as magical realist. The mystical realm is part of our ancestry, especially within Haitian Vodou and worship rituals. I can’t separate Vodou from how we identify as Haitians and how I — coming from the diaspora — conceptualise it, having left Haiti when I was six years old. As I am grappling with my own personal anecdotal history and those histories that have been passed down orally, you can’t not include mysticism, mythology, Vodou and magical realism. That language has to be part of how I tell the immigrant story. The oral archive, for me, is just as important as the supposedly “stable” historical archive. The oral archive is organic, it is living and it is contained in the bodies of me, my siblings and our ancestors. That archive is just as important to me. I want to think about, when lighting comes from the sky, how does that remap an event as it lives in my memory? Now, that’s a different kind of realism.

Credits

All paintings courtesy of James Fuentes LLC.