Up in north-west England, the ancient town of Workington sits at the mouth of the River Derwent on the Cumbrian coast. Its history mirrors the fate of empires that have passed over its land, beginning with the Romans, who erected forts and watchtowers to protect it from the Scoti of Ireland and the Caledonii of Scotland during the first century AD.

During the Industrial Revolution, Workington became a vital hub for coal mining and steelworks used to produce railway rails that were exported to every corner of the globe. Under British colonial rule, once pristine landscapes were razed so that railways could be built to transport natural resources from subjugated lands. “You can go around the world and come across Workington Rails,” says photographer Peter Fryer, who chronicled the town over a period of two years with a grant from the Art Council of Great Britain, now collected in the three-volume set Workington 1982-1983 (Café Royal Books).

With the disintegration of the British Empire following World War II, the nation fell into a downward spiral that ultimately led to the collapse of industry across the north. By the 70s, conditions had become bleak, and working-class communities that once depended on mines and factories began to struggle. Inspired by British documentary photographers such as Chris Killip and Graham Smith, Peter was inspired to travel north to explore how the people of Workington were adapting to the challenges they faced. “It was people on the edge,” Peter says.

In 1982, Peter left London for the project, not realising he would never again live in the south. “To get to Workington, you have to travel through the Lake District, the mountains and hills where everyone goes on holiday, to reach the coast — this wonderful cacophony of stories and characters,” he says. “When I arrived, the steelworks were closed, and the railways were coming to an end. But I think any piece of work should also celebrate the creativity, diversity, and resilience of the community.”

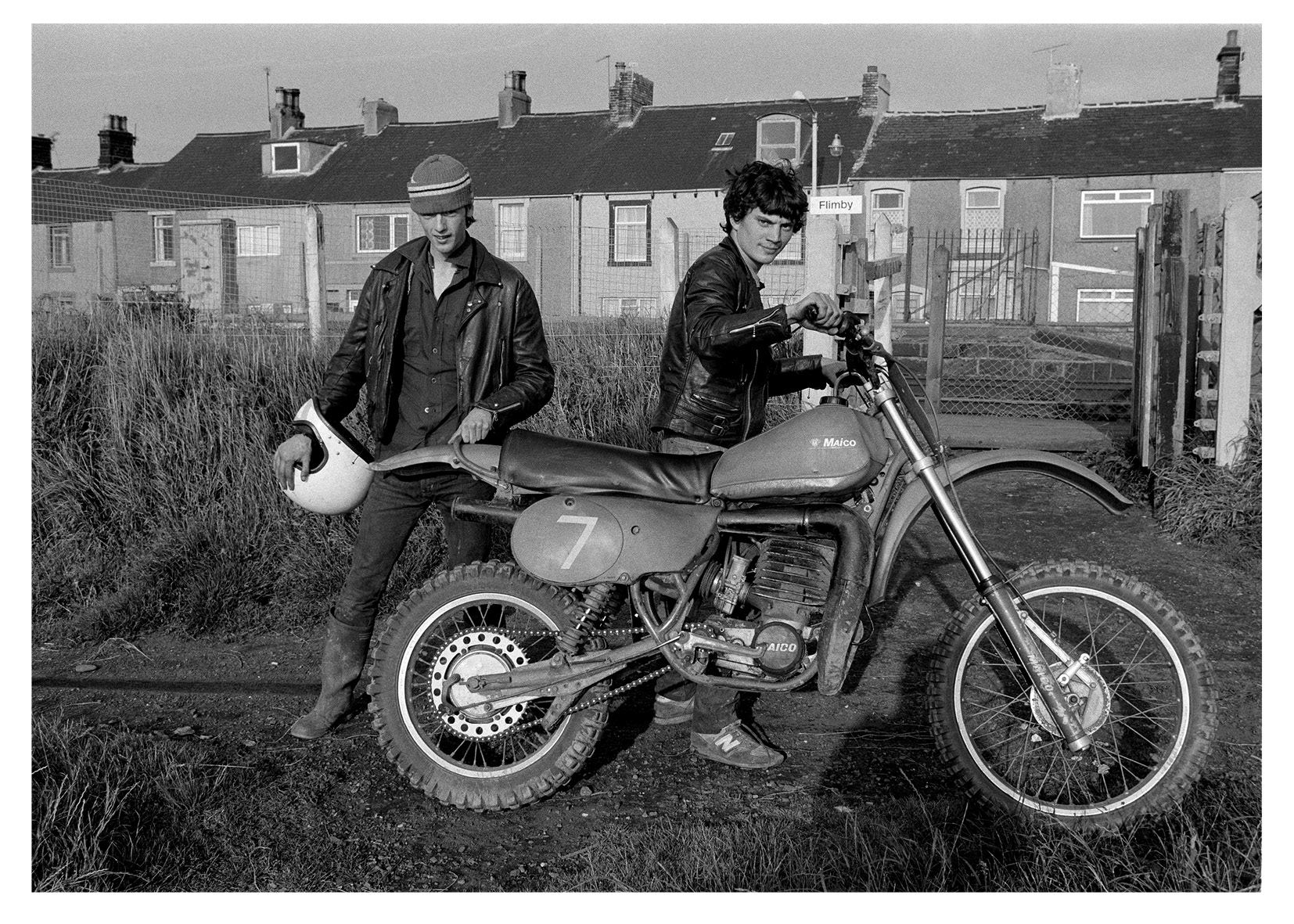

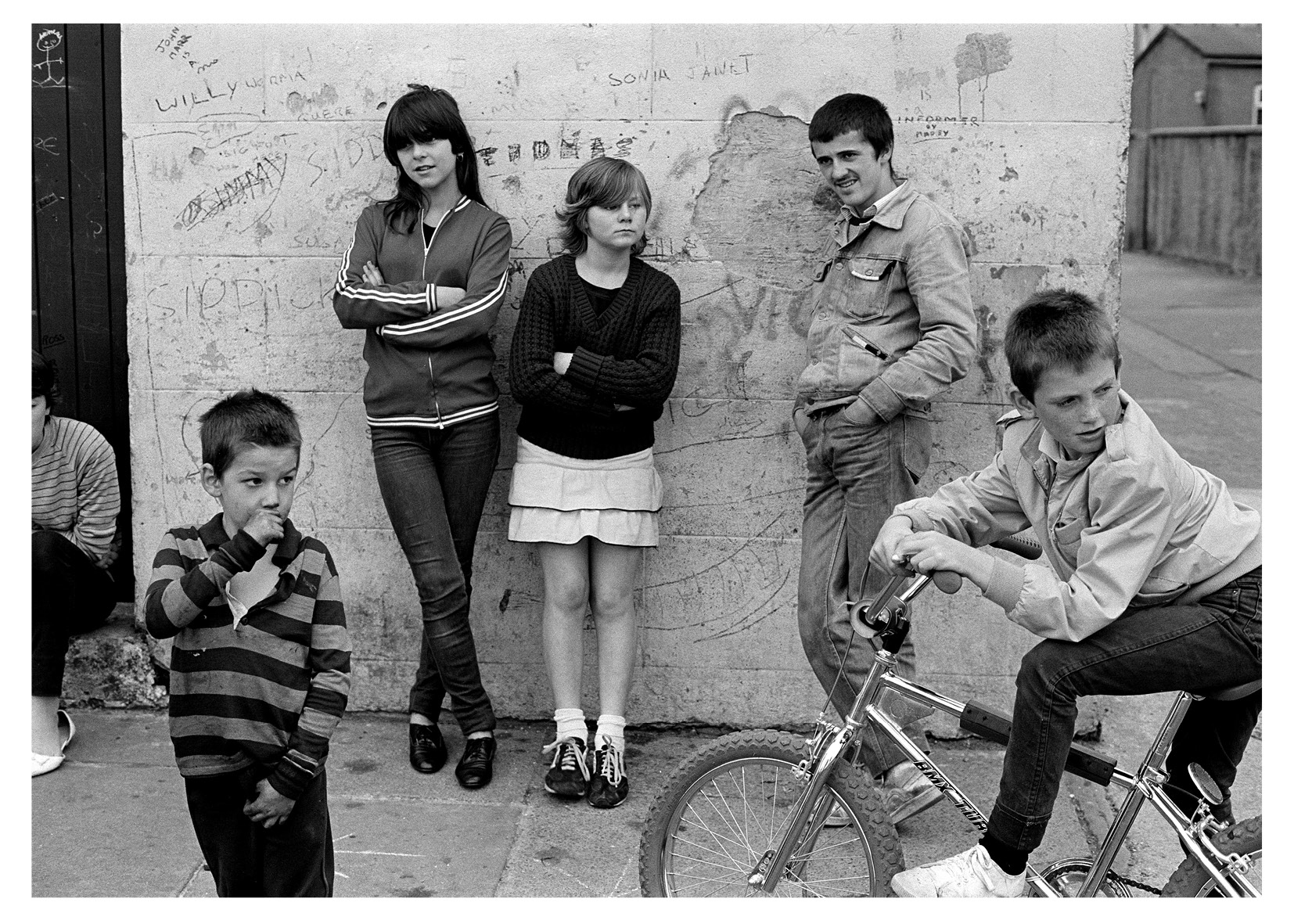

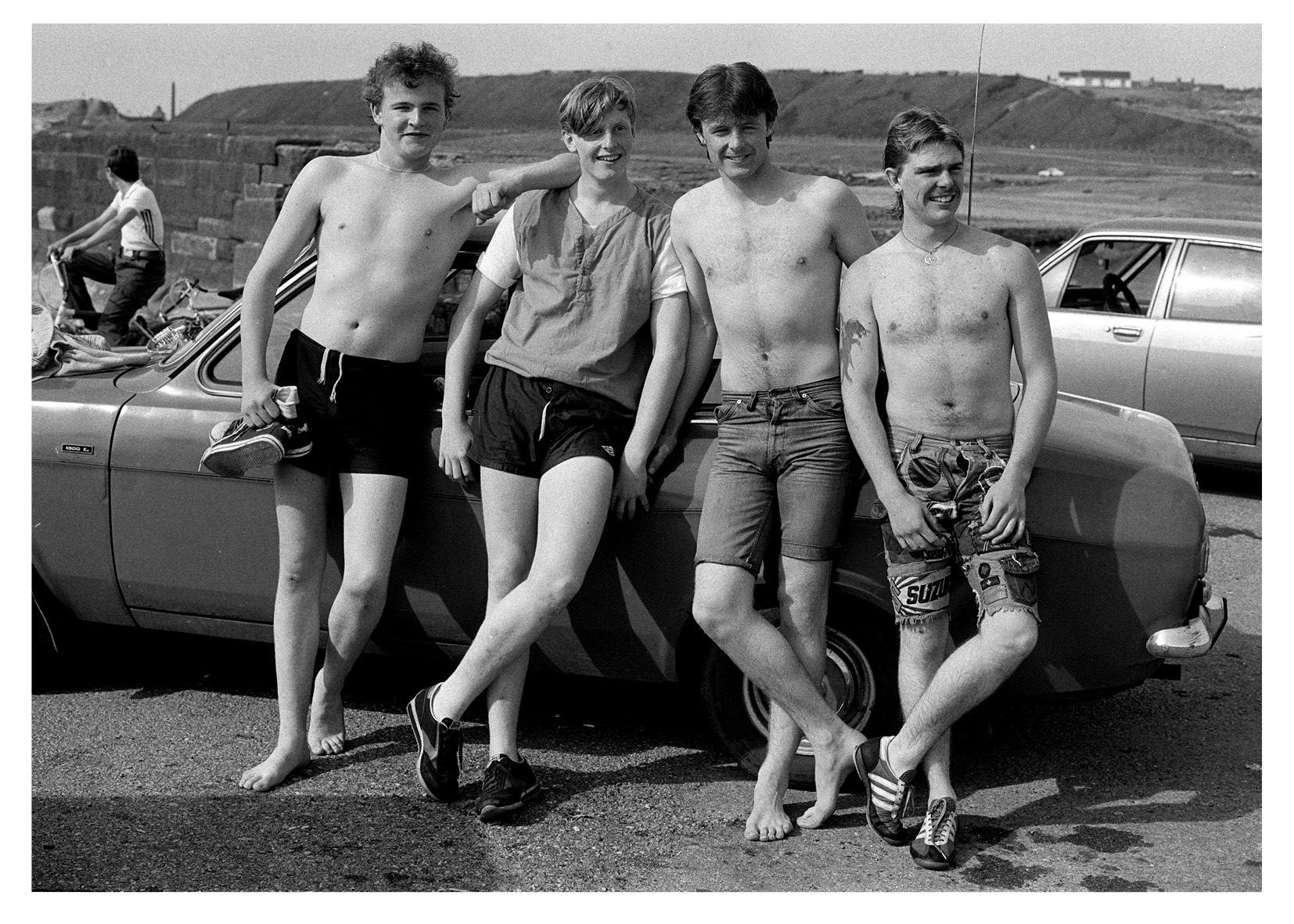

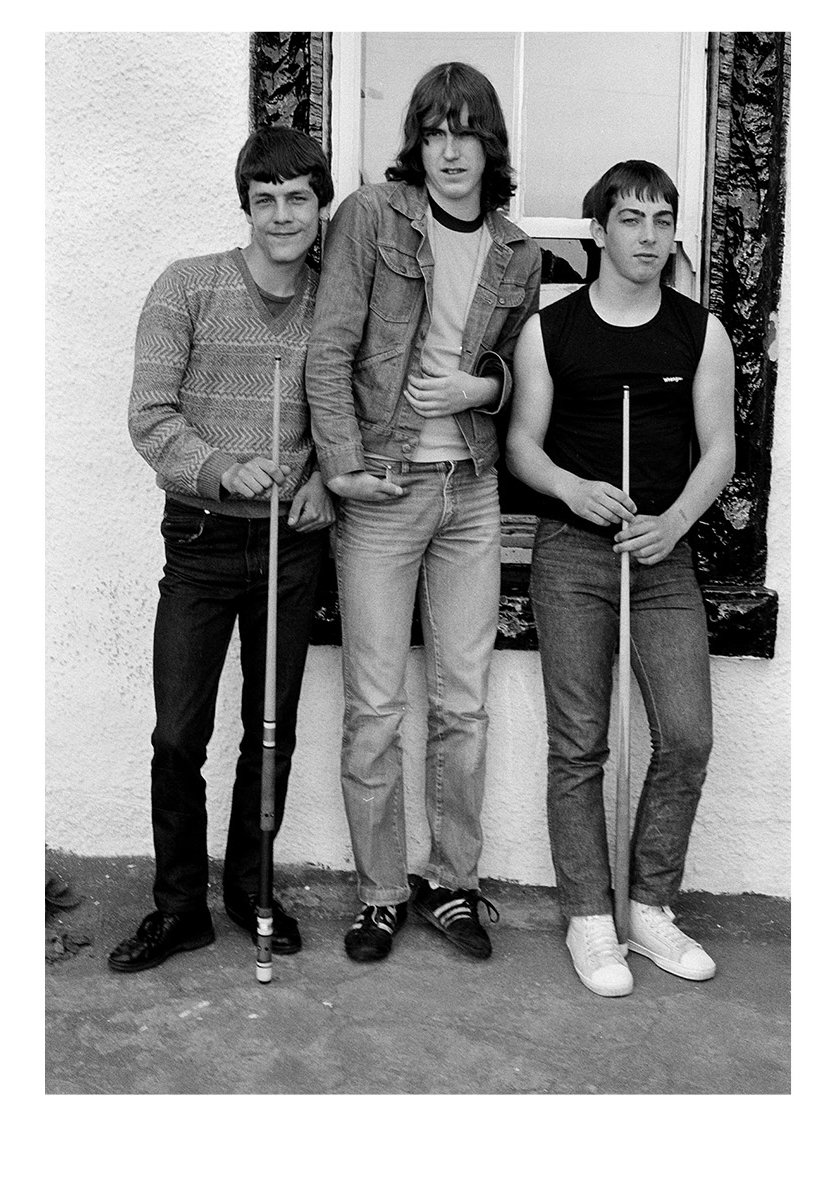

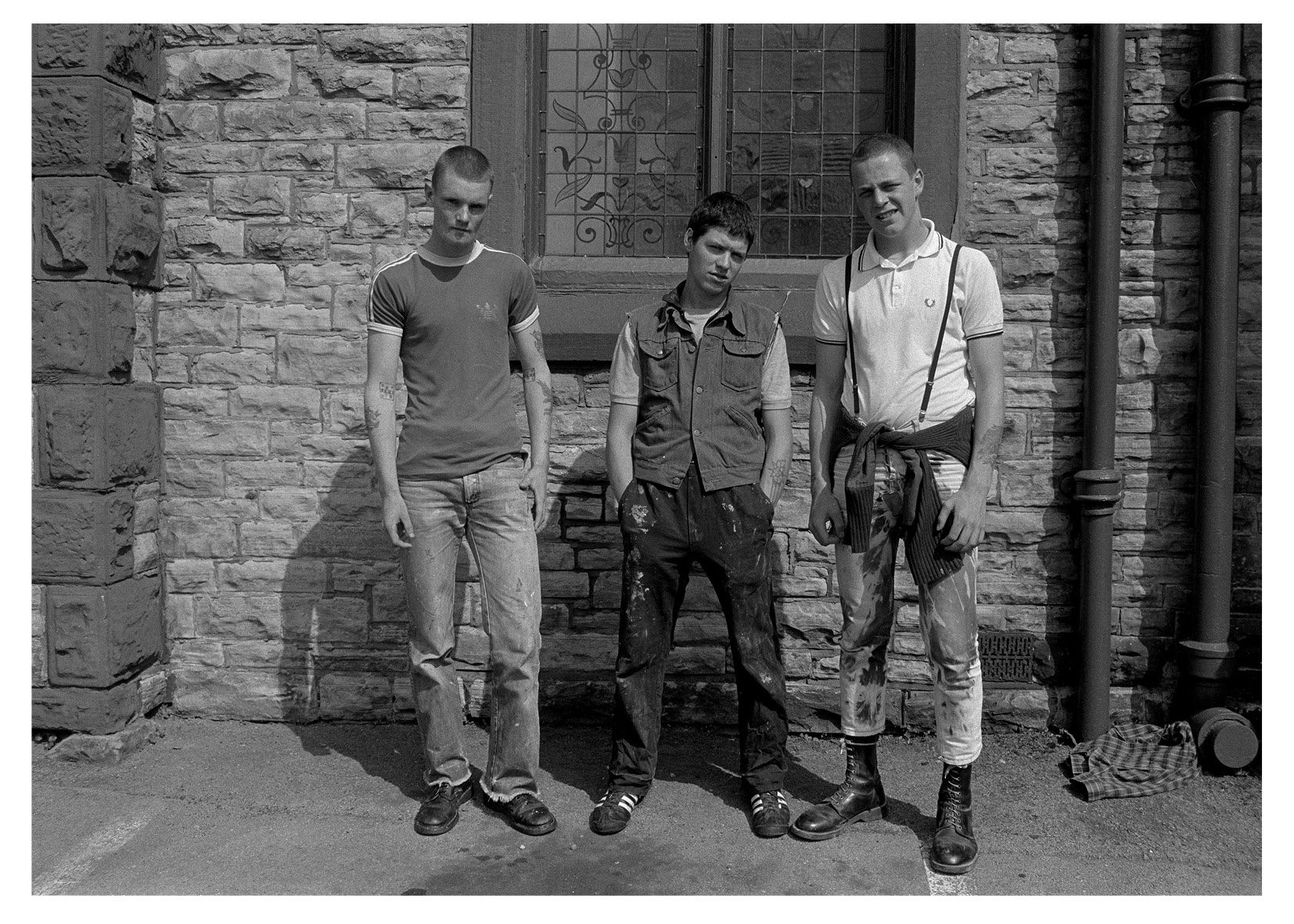

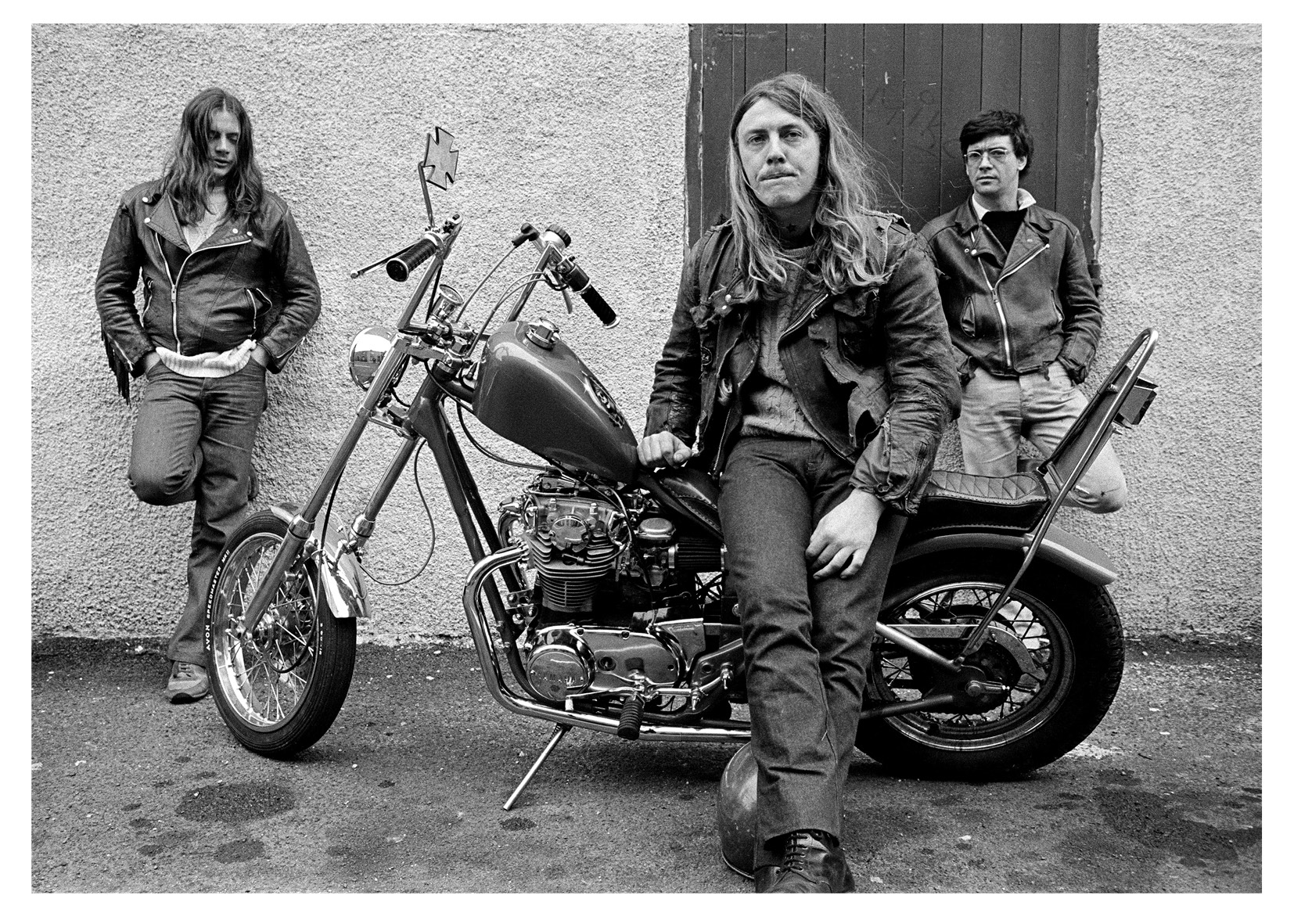

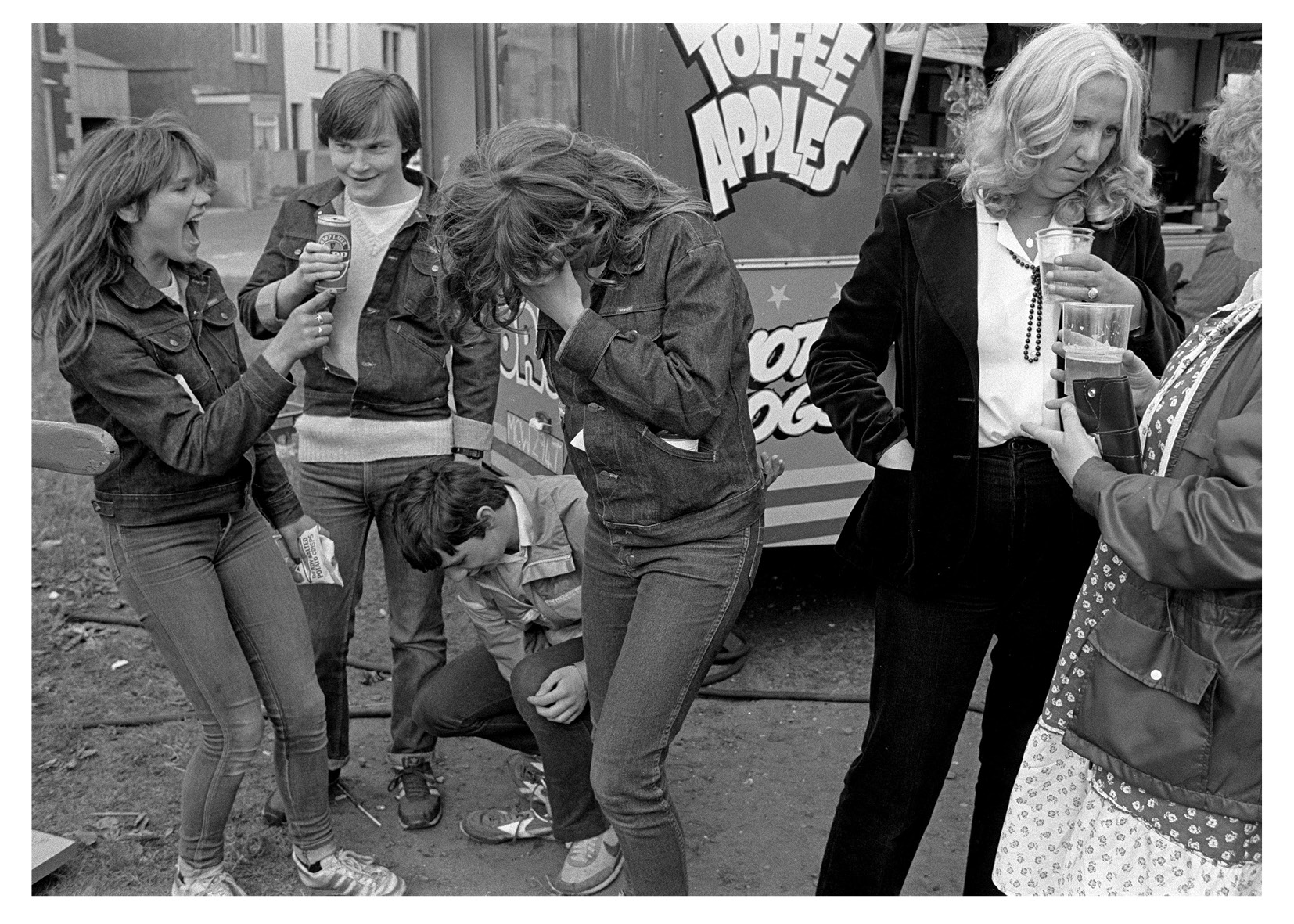

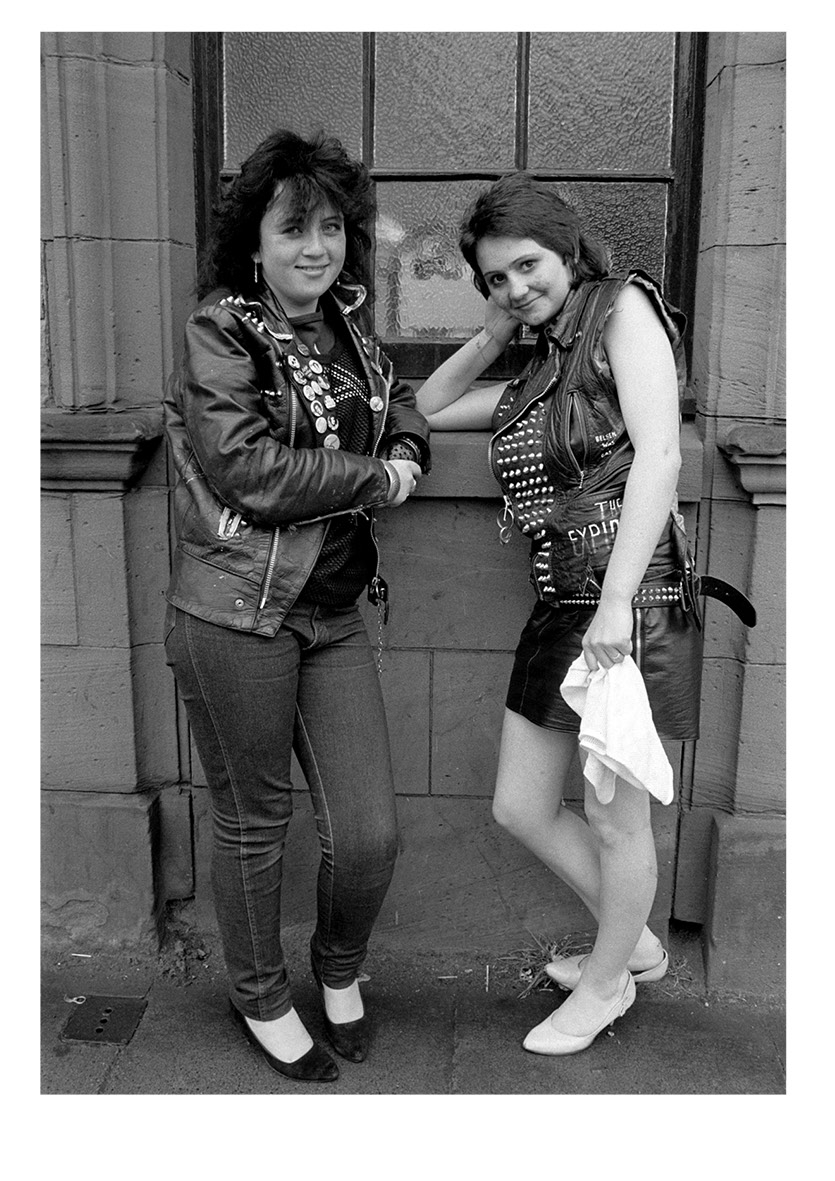

Although Workington was run down, the kids took to the streets and made the best of it. In this little corner of the UK, various subcultures like Ted, Rockers, and Skins flourished in the rubble. Peter quickly became fully immersed in Workington’s daily life. “All my work takes place in small confines,” he says. “I walk miles and talk for ages, getting entrenched in what people are saying — and then suddenly remember I have to be a photographer. That’s the usual course. People will say, ‘Oh well, you photographed me out in the street, you better come back for a sandwich and a cup of tea.'”

Peter honed his documentary practice during his years in Workington, using the camera to bridge the gap between insider and outsider. After securing a flat over a photography shop (where he was given total access to the darkroom), Peter asked the proprietor where he might go for a drink. The shop owner told him about three pubs, the last on the list he cautioned with, “You don’t want to go into that one” — so naturally Peter went. When he arrived, a hush fell over the room. Word was out; a photographer had come to town.

The chatter of the local pub worked to Peter’s advantage, not just for the project at hand. He built a community darkroom from scratch in an employment centre dedicated to helping those who lost their jobs when the steelworks closed. At the centre, Peter gave weekly lessons and classes, sharing the wealth of his knowledge with those looking to learn a new skill or take up a meaningful hobby. “Whenever you work somewhere, you have to give something back,” he says. “As photographers, we are privileged in that we have a commodity and a currency that can easily be given back. It’s wonderful that you can come back and bring a print.”

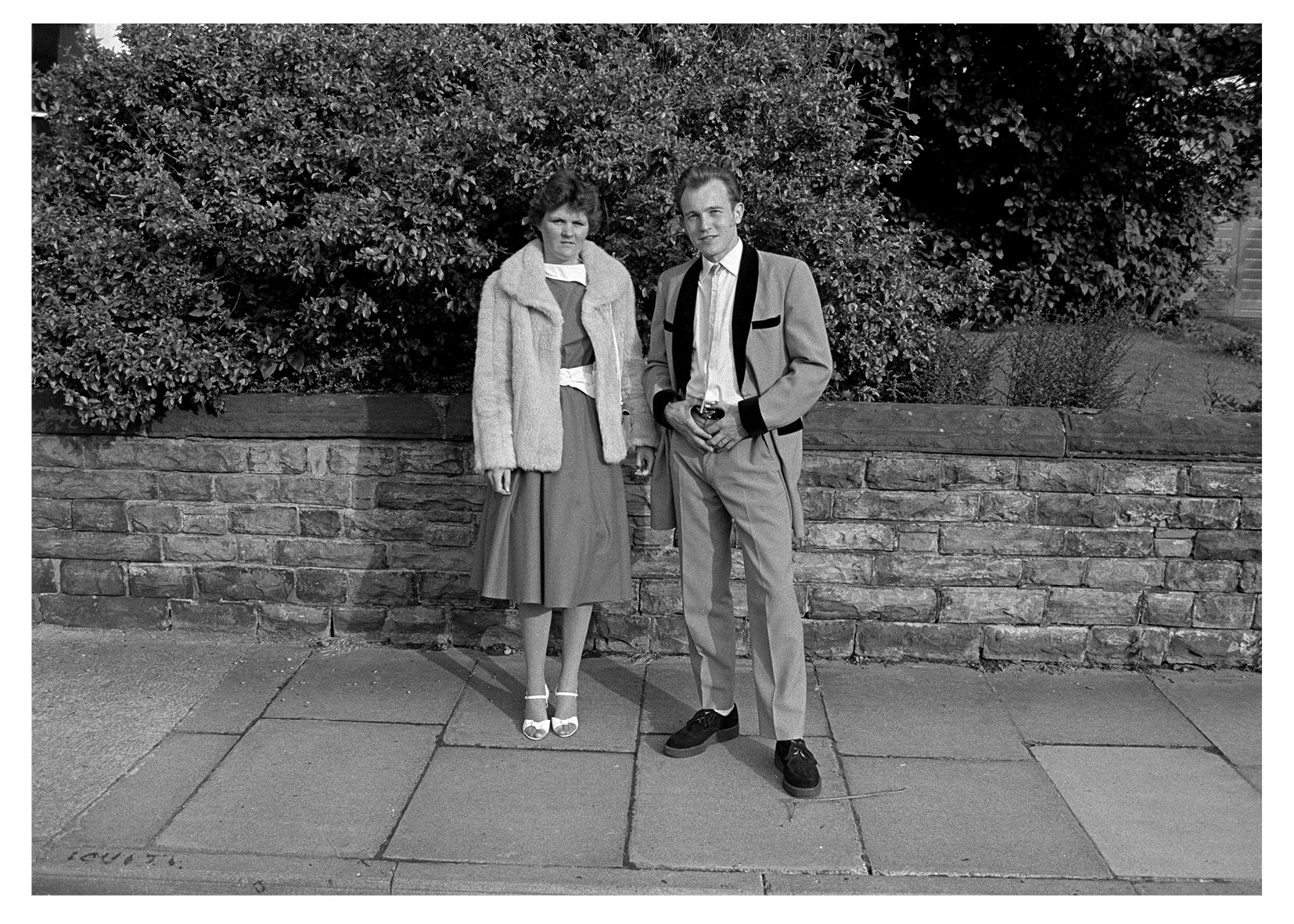

In those encounters, new opportunities may arise for ongoing collaborative work. Or something even more magical might occur. Peter points to the photograph of the Rockabilly couple dressed for a night on the town. They are a picture of Ted glamour: she in a fur coat and open-toe sandals, he in a vintage suit and creepers. “They were walking down the street looking stunning,” Peter says.

Recently the couple’s daughter had gotten in touch; she saw the photograph online, and Peter sent her a print. “Her mother had died, but her father was still alive, and she told me, ‘He remembers you taking the photograph,'” Peter says, quite surprised that the memory of their encounter remained 40 years later. “We had a brief conversation. They asked what the hell I was doing, and then we went our separate ways. That things should come full circle with the daughter contacting me is absolutely brilliant.”

Working on the street, rather than in the studio, Peter brought photography to the people long before digital technology democratised the medium and made the practice of street portraiture an everyday event. At the time, personal cameras were largely reserved for recording important moments like birthdays, weddings, and holidays. Few people encountered documentary or street photographers, and even fewer were asked if they might pose for a portrait simply because there was something irresistible about their energy and their look.

“People were usually bemused by it. They would ask, ‘Why do you want to take my picture? What’s important about me?’ I think we don’t build ourselves up much,” Peter says. “They assumed you were with the local press rather than somebody who wants to show a small slice of life that hasn’t been seen before. It’s not my right to invade somebody’s space for my benefit. It’s important to ask people how they see themselves and how they want to be seen.”

Pointing to the photograph of the young man leaning against his motorcycle, Peter observes, “He’s proud of it, so he’s posed on it, and he’s comfortable. In a way, he’s in his own space. I’m not a fashion photographer, but these pictures talk particularly about that. They’re very telling of an age of black-and-white documentary photography, and it makes you look at people and places very different from when you are working in colour.”

Credits

All images courtesy Peter Fryer and Café Royal Books