We asked writers to pick one of the 111 items in MoMA’s monumental new fashion exhibition, Items: Is Fashion Modern?, and share an ode to its significance.

A bandana is not much. Thin as a sheet, wide and long as a forearm. It is an item that doesn’t tell you what to do with it. There are no buttons to hold it together, no tunnels the shape of your limbs, no seams to align with your waist. It is two-dimensional and shapeless until you take it upon yourself to hook it around your forehead, twist it across your neck, or blanket it over your hair. It is a thing of possibility.

For three important minutes of my early adolescence, I wore a bandana as a shirt.

On a significant but undateable July night, all the cool girls (there were four) decided to tie bandanas over their torsos, as an outfit for an important summer event. Though I was not categorically a cool girl, they were my main-hangs; I can’t explain it, other than to say early adolescence is a strange and liminal state, as strange and short as the few minutes that I wore a bandana instead of a shirt. Oh, this is ridiculous, I thought, and found an alternative top and tied the bandana around my wrist. The bandanas caused a commotion at the important summer event and I found my place at the edge of things. My bandana choice had separated me, I thought, very smug and more mature than everyone surrounding me.

Then, a few summers later, these girls would scurry around me to fashion me a love-bite cover-up that I could reasonably wear with a bathing suit (I was teaching sailing and had kissed someone for too long in the woods the night before). One knotted a bandana tightly around my neck and for an interminable week, I was called “‘Danner.” In sum, the bandana will make its purpose known to you.

A square cloth is an unknowably ancient item, though the Anglicized word bandana dates to the 1800s and is often associated with the Persian paisley pattern that is meant to evoke a flowering spring or a bent cedar tree.

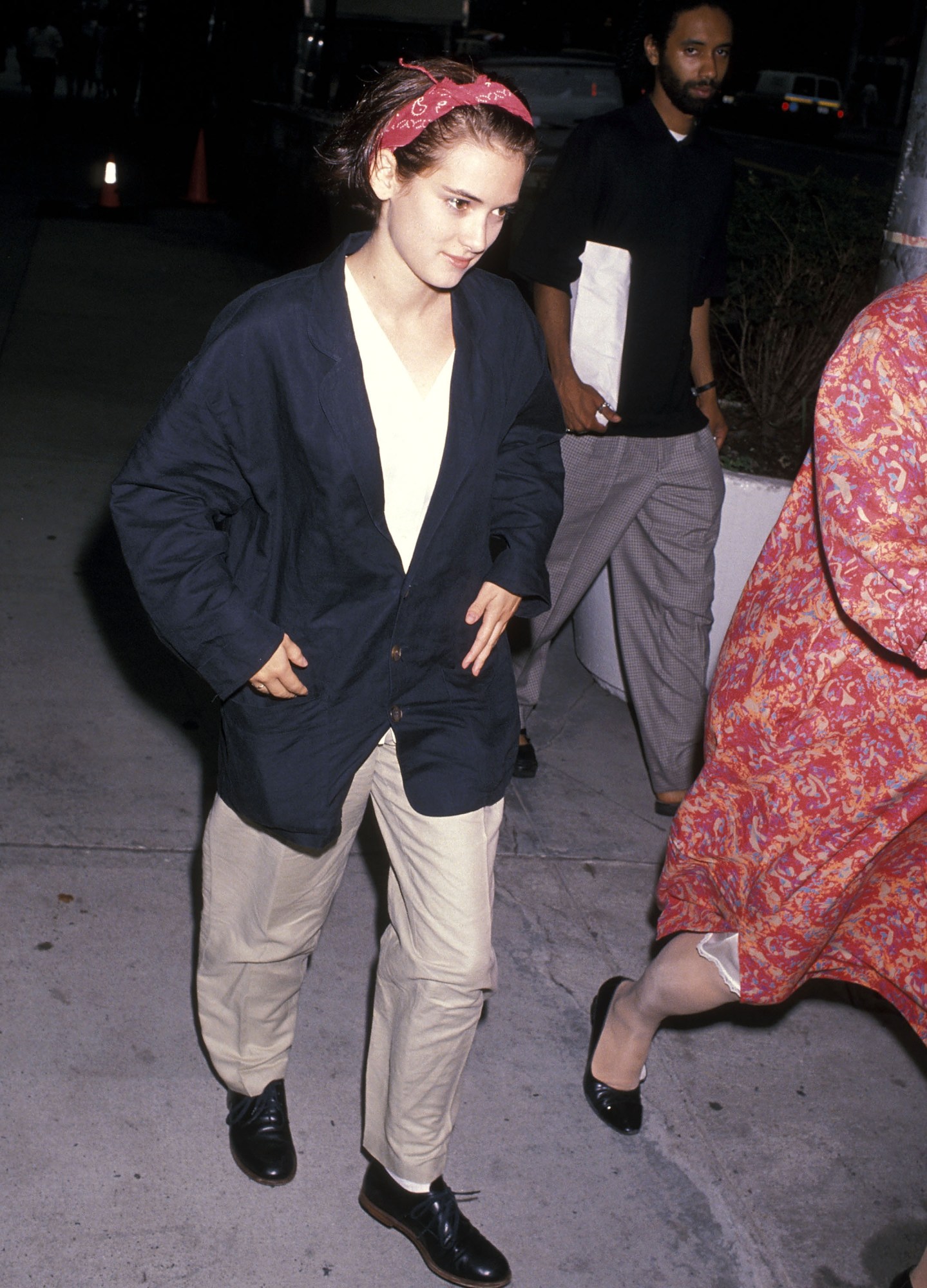

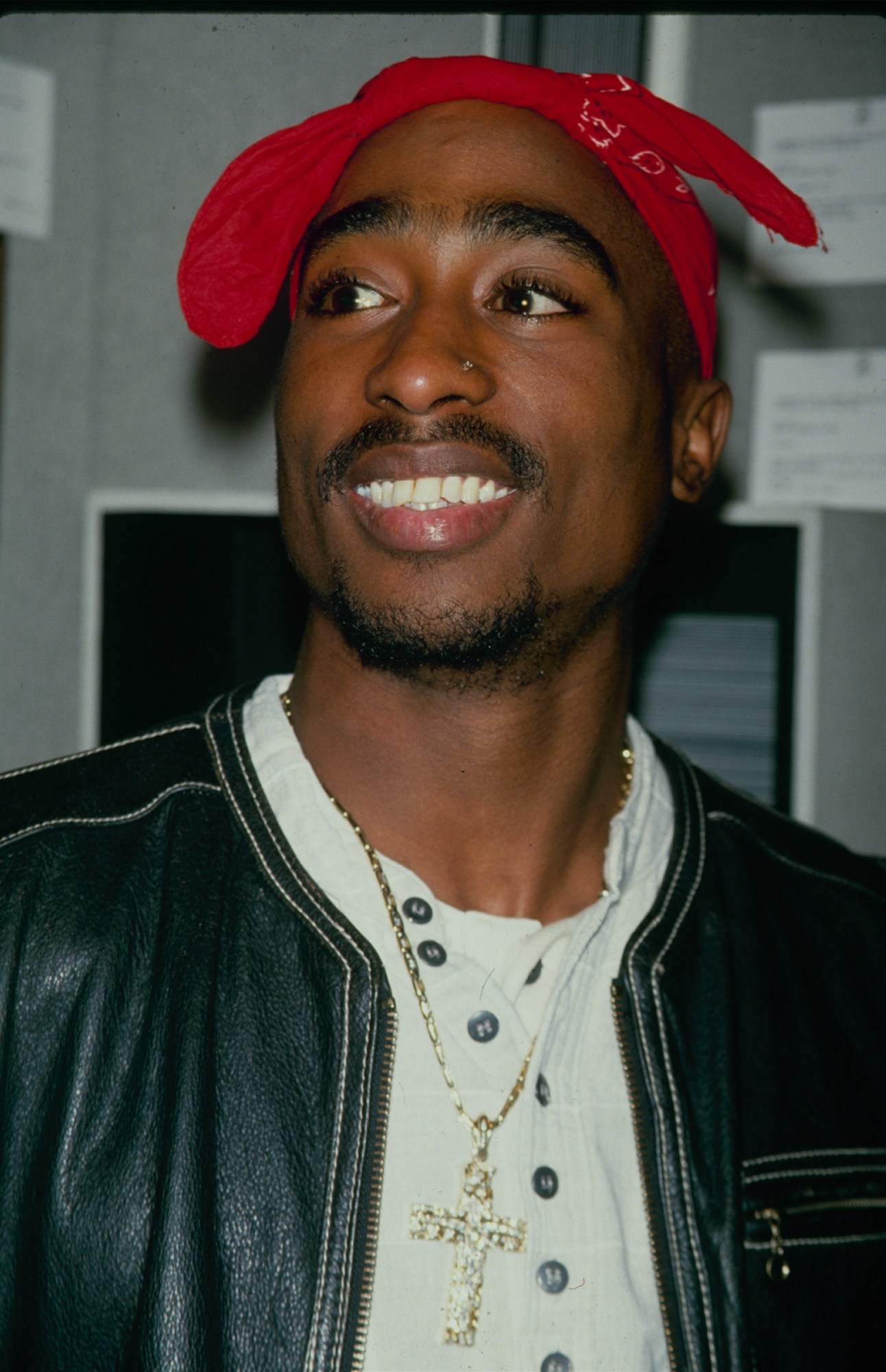

Today, the bandana’s affiliated parties are many: cowboys, pirates, farmers, housekeepers, punk bank robbers, pin-the-tail-on-the-donkey players, motorcycle gangs, California gangs, lots of other gangs, stadium concert heartthrobs keeping their famous sweat off of their famous eyes, cruisers, BDSM seekers who know what they want or want to give, American revolutionaries, unionizing coal miners, Dust Bowl sufferers, 90s red carpet heroes, WWII shipyard workers with long hair. The bandana is integral to an obscene number of looks. If you have a bandana you have a costume.

Related: Decoding the Secret Language of Gay 70s San Francisco

So do not mistake versatility for agreeability, or formlessness for uselessness. The bandana’s main strength, perhaps, is resilience: it’s bent one way, it returns, it bends another (and I do not defend its use as a shirt, but it has been done). It exists to be tied and retied again; the word bandana is from the Sanskrit meaning for “a bond” or Hindi word for “he ties.”

Particularly, the bandana wants to be tied around the neck, though wrist and forehead are also suitable. Around the neck, it looks the most poised to be useful, and the bandana exists to be poised. During early backpacking trips, I was informed that the bandana has a Swiss Army knife range of potential uses. It can shield a face during a dust storm. It can be hoisted as a sling for a wounded arm, tied as a tourniquet, it can mop sweat, contain snot, stop blood. You could gather blueberries in it, if you live in a rustic dream. It can be used as a shoddy oven-mit to move pots around a campfire, a cloth napkin for the same meal. It protects from sand, wind, cold, sun, identification. For one forehead in particular (Jimi Hendrix’s, supposedly), it delivered LSD into a small cut and right into his bloodstream. It exists to be purposed. A bandana says, You have me, now what are you going to do with me?

A crush who often wears a bandana — and had one cresting out of their pocket at the time of inquiry — told me a friend designs them with intricate patterns. The friend gives them as gifts and asks everyone to interpret what the prints mean for their sex lives — an extrapolation of flagging, a gay cruising code in which bandana color and placement signals particular interests. In the 1970s some stores in San Francisco would even sell bandanas with helpful placards that indicated their meaning. The Leatherman’s Handbook II from the 70s is still the authoritative chart, though the author Larry Townsend encourages double-checking, because, as he puts it, some people are innocent and some people are just into bandanas. There is a code with specific designations, but many times the idea of evoking the code was enough of a turn-on. As always, flexibility and adaptability is the way of the bandana. The print on my crush’s kerchief is little ivy leafs. We couldn’t settle on a meaning. My only bandana (currently tied around a rung of a bookcase) has a geometric design, which couldn’t mean anything other than a well-ordered sex life.

The bandana is literally square, but it is anything but. It’s a small thing with potential for many meanings. It can signal to loves, enemies, friends, rabble-rousers. But keep in mind that a bandana is also a cheap and disposable thing. It’s associated with hard-living ranchers and women’s employment propaganda but it also looks great on a dog. It’s not all so serious.