We’re bombarded with evidence of how many times artists say ‘yes.’ We see that they say ‘yes’ to appearing in TV commercials, and we see that they say ‘yes’ to turning their videos into TV commercials. We see that they say ‘yes’ to endless tours they don’t enjoy, to product endorsement details and to sponsored tweets — to video treatments they’re not sure about, to supposedly helpful A&R suggestions they can’t refuse.

We see so much evidence of yes, that we rarely pause to consider the evidence of no.

‘No’ is the most powerful word in any artist’s vocabulary. At its most extreme, the ability and desire to say ‘no’ can means the difference between career longevity and speedy burnout. As the past week has shown, it’s also the difference between Adele and nearly everyone else.

In the last few years Adele has said ‘no, I won’t turn up to all these events to boost my profile.’ ‘No, I won’t rinse the ass off social media.’ ‘No, I won’t do live dates I don’t want to do.’ And ‘no, I won’t do any old shit for cash.’ Most significantly, she’s said ‘no — I will not rush my album.’ In terms of going against the music industry grain, the gap between 21 and last week’s appearance of Hello is one of the most punk statements in recent pop memory. That radio silence was quietly — completely inaudibly — subversive. In an era when artists are routinely celebrated for doing near to nothing, we can genuinely celebrate Adele for doing literally nothing.

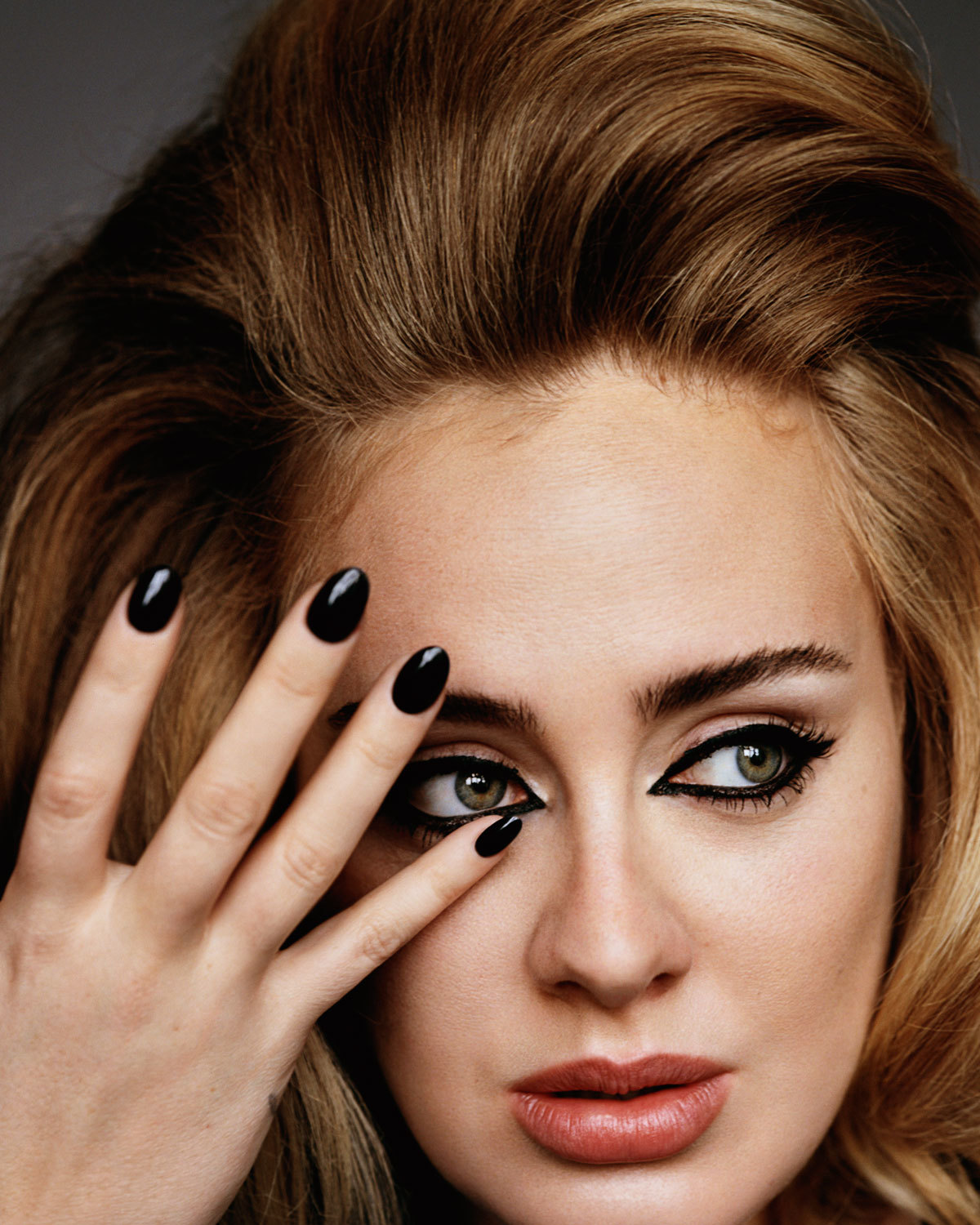

READ Adele’s full cover story from the new issue of i-D here

The simple fact is that you can’t stage a decent comeback if you’ve never really been away. When artists are still touring their last album when the first single from the next album is in the charts, is it any surprise that so-called comebacks are met with weary coverage and underwhelming sales?

That Adele’s managed to break so many records in the last few days without breaking a sweat comes down to the most basic laws of supply and demand: if you reduce supply, you increase perceived value. In doing this, Adele found a way to achieve the shock and awe impact of Beyoncé’s boom-there-it-is 2014 album release, while sticking to what is, in many ways, a fairly traditional release strategy.

Total radio silence is so rare in pop. Take Rihanna, who hasn’t released an album for 1,075 days and is now at the point where the very idea of a new Rihanna album is a running joke in some quarters. Even with its title and artwork revealed, it feels like something future generations might simply refer to it as an elaborate, ludicrous myth, like Jason’s golden fleece, the tooth fairy, or Jason Derulo. But when she does drop Anti it will come after a year’s worth of visibility: numerous product endorsements like sneakers and socks, fragrance launches, single releases, a movie, and a slew of magazine covers. It’ll make a big impact — but imagine how much bigger that impact could have been if Rihanna had been AWOL for three years. Most A-list stars — and their managers — seem scared not to fill their time by appearing at events. They’re always flogging something, they always seem to get themselves in the news, and always feel they need to keep their profile high. Again, Adele said ‘no.’

Fine, so being able to do this is a luxury that comes with nearly 30m sales of your previous album. It’s also true that Adele’s dignified silence is not an approach that would suit, for instance, Miley Cyrus. But the fact that so few artists could emulate Adele’s career path is just further evidence that Adele is a very special artist.

She’s benefited from a special set circumstances, too. Here’s a mainstream artist who’s been nurtured by XL Recordings, an independent label with the clout and expertise of a major but an ability to step back from the nonsense that annihilates so many major label artist careers, in order to deliver an artist-centric philosophy that’s also allowed singleminded artists like Thom Yorke and Jack White to sell vast quantities without compromise. Early on XL’s vision percolated into another area of Adele’s sympathetic infrastructure: it was the man who signed Adele to XL who introduced Adele to her manager, Jonathan Dickins. Apparently by complete coincidence, Dickins’ sister also became Adele’s agent. It’s depressingly rare for an artist to exist in a label and management framework where clarity of vision and that artist’s best interests are genuinely prioritised. But that’s what seems to have happened with Adele.

Even if we focus on one apparently minor detail of her comeback — the use of a flip-phone in the Hello video — we see Total Adele. The video’s director explained last week that the flip phone used in the video was deliberately unorthodox. “I never like filming modern phones or cars,” Xavier Dolan told the Los Angeles Times. “They’re so implanted in our lives that when you see them in movies you’re reminded you’re in reality. If you see an iPhone or a Toyota in a movie, they’re anti-narrative, they take you out of the story … It feels like I’m making a commercial.”

Dolan’s wish didn’t completely work, because the unexpected appearance of an old flip-phone created its own attention on social media. But that in turn shone a spotlight on something so important: we find that flip-phone jarring because we expect phones in videos to be modern branded smartphones. Because that’s all we’ve been seeing in videos. It’s like when you glance away from a lightbulb. Adele’s use of a flip-phone is an anti-endorsement statement in a cash-obsessed industry. It’s hard to think of any other global mainstream artist who would feature a phone during the pivotal moment in their video and not see it as an opportunity for a six-figure payday.

We’re told that product placement is a necessary reality of the modern music industry, but Adele has taken two steps to the left and defined her own reality: while peers are huffing and puffing their way up the pop world’s increasingly steep flight of stairs, she’d gliding up an escalator.

It was no accident and of no little significance that the first time anyone heard Hello was totally on Adele’s terms — in the advertisement that appeared on national TV, out of nowhere, two weekends ago. There was no mediation: no journalist or website was given the exclusive first listen; there were no reviews that could shape opinion. Similarly, there was no pissing contest between radio stations for the first play of the song — Hello was available on streaming services before radio stations could give it the ‘first play’. Adele went straight to her audience.

One of the enjoyable things about watching this campaign roll out has been the way in which Adele has totally embraced her true audience. By debuting that ad during a primetime show like The X Factor, Adele took bold ownership of her place in popular culture. You don’t go 7x platinum in the UK alone without selling albums to X Factor viewers — much as some credibilty-obsessed artists might try to kid themselves otherwise. And while the ‘XL’ side of her artistry may have come through in the choice to give an exclusive print interview to i-D instead of, say, The Sun, she also paid a visit to both Radio 1 and Radio 2 on the morning her single dropped.

Those radio chats, along with i-D’s own frank and funny interview, were a good reminder of why Adele was taken to the world’s heart during the 21 campaign: she’s smart, warm, bold (there might be sadness and regret in her music but she never plays the victim) and very funny. On Chris Evans’ Radio 2 show she howled with good-natured laughter when he mistakenly asked about her alter-ego Sasha Fierce. She also agreed to attend a charity night at his pub, but joked that he should bring back Don’t Forget Your Toothbrush when asked to appear on Evans’ revived TFI Friday. Over on Radio 1 she was guffawing at the fact that her big comeback ad followed one for pizzas, announced that she needed to both belch and go to the toilet, and laughed that “I thought I’d missed me window” when telling the story of how she searched her name on Twitter after the ad aired and only saw three tweets.

Nick Grimshaw noted that the ad represented “a moment”, adding: “I felt like the country stopped for a second.” Sidestepping X Factor‘s freefalling viewing figures for a moment, he was spot on. Adele’s comeback became a huge a focal point and a good example of collective experience in an era when music launches routinely feel fragmented across divergent social networks and splintered fanbases.

“I think everyone could have their moment if they didn’t share everything all the time,” is how Adele replied. “The only reason people seem to have reacted how you’re saying is that I haven’t been doing anything else. I want to surprise people, I don’t wanna say something for the sake of it: I had nothing to say, why am I going to say anything?”

Those are words worth reading, re-reading, memorizing, then assembling into a 30ft-high neon sign to plant outside the front door of your nearest record label. Adele might be a one-off, but there’s plenty we can all learn from her.

Read more from Peter over on Popjustice

Credits

Text Peter Robinson

Photography Alasdair McLellan

Fashion director Alastair McKimm