This article originally appeared in i-D’s The Earthwise Issue, no. 353, Fall 2018.

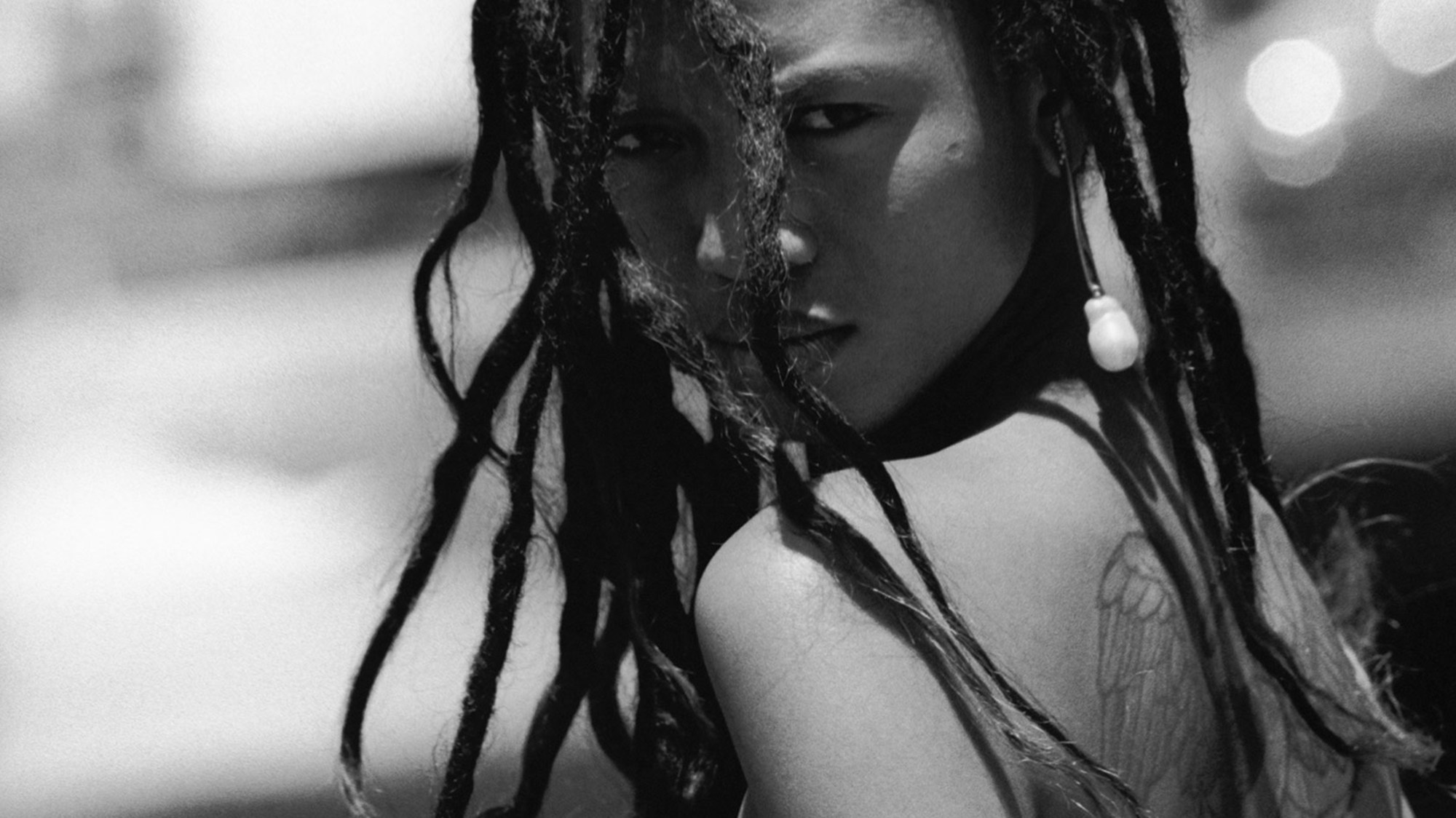

Adesuwa Aighewi walks into The Spurstowe Arms in east London carrying a large packet of crisps. She is dressed in very summery all white except for a pair of big black and red cowboy boots at the end of her long legs. She is strikingly beautiful, dreads tied up, a tangle of silver necklaces around her neck, no make-up on her skin. Those cowboy boots though… “I drew them and I had someone make them, it took three months. These boots taught me patience! These boots are moulded to my feet, I’m wearing these bitches till I die,” she says.

Every once in awhile a model comes along who manages to really grab the fashion world’s notoriously short attention span, maybe even manages to hold it. It’s indefinable as to why exactly she rises above the rest. She will have something zeitgeisty about her. She’ll radiate a mood that is totally infectious. She’ll signal a new feeling that everyone everyone wants a little piece of, and then a lot pieces of. Somehow that girl can transpose all of that elusive who-is-she power into a still image.

Right now, that girl is Adesuwa. With increasing regularity, she is showing up in the fashion world. And really she’s just what we need. In the face of a messy, exhausting, so-shocking-it’s-no-longer-shocking world that most are responding to with detached irony, Adesuwa emits an irresistible sense of aliveness, a willingness to call out bullshit but also to let herself really feel good when she feels good.

Part of Adesuwa’s draw is that she doesn’t really give a fuck. Doesn’t really care what you think of her. But that’s balanced with a real thoughtfulness, which is equally important to the mystery of her magnetism. The thing is, she does really care, it’s just that she’s managed to hone it on a few essential things, the rest isn’t worth worrying about. Another clear part of her draw is her multiculturalism. Adesuwa’s dad is from Nigeria, her mum is Chinese-Thai, and she grew up in America and Nigeria. Her rise is at least partly indicative of a social demand for diversity. Amidst a political reckoning with widespread inequality and deeply ingrained racism, there is no longer room for fashion to be complacent.

Though Adesuwa’s been modelling for around 10 years, it’s in the last six months that things got a bit mad for the 26-year-old. She’s suddenly broken through the ranks of working model in heavily in demand girl of the moment. Is it because of her dreads, which make her stand out? She was advised against getting them, that is would make her harder to work with, but ignored that guidance.” I dunno to be honest, I think I just got lucky I guess.”

“I’ve kept quiet up until now, because if I was a black woman yelling about equality, everyone would be like, ‘Oh, that crazy bitch’. But if I’m ‘Adesuwa, the famous model’, they’re like, ‘Ohhh how can we help?’”

New York is home for her currently, but she’s only been there for a handful of days since the beginning of the year, instead going from country to country, hotel to hotel, shoot to shoot to show to show. The demand for Adesuwa is only intensifying. She was everywhere you looked on the spring/summer 19 runways. She just killed couture. “Oh yeah, that was tight!” She says. “I felt like Beyoncé the whole time.” She’s a new favourite of Karl Lagerfeld, walking constantly for Fendi and Chanel. They’re on a first name basis.

Adesuwa is the daughter of two environmental scientists, and one of four kids. Her parents met while they were both studying in the US. “My mom comes from a really wealthy family, my dad doesn’t, so imagine an asian woman and a really, really black man dating then. Interracial marriage only got abolished 50 years ago – when they started dating I guess it wasn’t that bad but they still told me about how when they went to a bar people would be like, ‘You guys can’t come in’. This was in the 80s!”

The Aighewi family moved back to Nigeria when Adesuwa was young, so the kids could experience the culture and values of the country. With two academics for parents, her early years were heavily focused on education. “I wasn’t very social, it was very like: read your books, and when you come home read more books. I would go to school, I would come home and have a tutor. When my parents came home I would have to review my schoolwork with them. They were very rigid, like, ‘You’re going to be a doctor.’”

And then her brother died. They were very close, a bond intensified by not being allowed to stray too far from home. Two introverted kids with their heads in books. “It changed the way that I thought. I realised that there was no reason to be shy, there was no reason to hold back. Death puts things in perspective like nothing else. It changed everything about me, because I used to hide behind him.”

The family moved back to America shortly after Adesuwa’s brother passed away. There were intensifying riots in Nigeria and it felt dangerous. Back in the US, she started university early, skipping two grades thanks to all that extra curricular. Though she wanted to study art her parents pushed her towards science, and she ended up interning at NASA. She was being continually scouted, but Adesuwa wasn’t interested in modelling until she realised how much she could earn. She realised that it could provide her a way to earn money while she figured out what she really wanted to do. Her initial experiences were marred by racism, though. At her first shoot she overheard the make-up artist say ‘I don’t have her colour’. “They made me feel so ugly I went to the bathroom and cried. The other girls were blonde and sexy and older. You know you always see Naomi and Tyra Banks talking about that and I was like, oh my god they were right, and this sucks!” It was all the more shocking because it was a foreign concept to her. “For African-Americans there is this glass ceiling above their heads, but I didn’t grow up that way. I grew up in Africa — where whatever you want, you can do.”

Adesuwa is open about the frankly hideous experiences she’s been through with modelling, she knows talking about it is important, for her, for others in the industry. “I didn’t take it seriously because it was making me depressed. My agent at the time was like: you need to get breast implants because we want you to do Victoria’s Secret. And I was like, I don’t want that. So I got my chest tattooed instead.” And the racism she’s experience from the beginning continued. “I used to get things like, ‘Adesuwa you can’t be in the sun you get too dark, you need to be more Asian than black’. I never understood racism until I started modelling, I never understood what it felt like to feel ugly based on your skin. I never felt that pain. I never felt small until I started modelling.”

Adesuwa stuck with modelling. She was raised to challenge injustice and to believe in her own ability. Losing her brother had galvanised her, she saw that the only way to keep moving forward to choose to find the good — without ignoring suffering. “If something bad happens there’s only two ways you can look at it. You let it take you in and you succumb to the pain, or you can use it as ammunition for something else.” Her sense of self remained strong. She managed, through bloody-minded determination, to use modelling for her own means. “I’ve always known that I wanted something bigger than me. I’ve always seen myself as a civil servant of the world. There are two ways to live, you can either live for yourself, or you can say, ‘I want to live for others’. Modelling is the only thing that I’ve done that was for me. One day I was like, ‘Ok Adesuwa, go to your castings, maybe get an agency that actually works and cares about you.’ That was the day I realised modelling was a tool, and I could use it to do what I want.”

She’s noticed a change in the industry, buoyed by the a shift in the wider culture. “What’s beautiful is that the world is changing so much, it’s so cool, like even with me being able to model right now with dreaded hair – people are saying no to prejudice, people are saying fuck that shit I deserve to be me, I am amazing too.” The push back against narrow definitions of beauty is forcing a change in business terms. “What’s happening now is that companies are recognising the buying power of black people, and that’s why you see more black models, it’s supply and demand.”

“I used to get things like, ‘Adesuwa you can’t be in the sun you get too dark, you need to be more Asian than black’. I never understood racism until I started modelling, I never understood what it felt like to feel ugly based on your skin. I never felt that pain. I never felt small until I started modelling.”

Planning, since that realisation, to channel modelling into projects that drive her, Adesuwa waited until her she was big enough, successful enough, and then she could make noise and be listened to. “I kept quiet, because if I was a black woman yelling about equality, everyone’s like ‘oh that crazy bitch’. But if I’m ‘Adesuwa the famous model’, they’re like, ohhh how can we help.” She isn’t sitting on some vague idea. She has big, brilliant plans. A TV show is in the works, with filming planned for later this year – Adesuwa has had directing ambitions for a while now. “The show is meant to educate people on what Africa is through an African’s point of view, but it’s gonna come with humour, so that it doesn’t feel like a PBS education.” The plan is to use the show to help change perceptions of the continent. To move the conversation away from the white saviour and towards showing the creativity, innovation and culture of African people. “I miss home so much, you feel free there. You can dream there. And the thing is that arts is the one of the biggest things in Africa, because there’s no TV in every house telling you what’s cool, so you get to be your own entity.”

With her scientist mind, and an obvious hunger to imbibe as much information, ideas, as are out there, Adesuwa is always watching, always asking questions. She’s really in the world. Modelling, with its continuous travel, has helped feed that drive. “There is so much to learn all around us, but sometimes we get into a tunnel vision. For me, I want to be 80 years old and look like I’ve lived life. You’ve seen those women that just look like they’ve really lived? That’s what I want to be. I think the next human evolution isn’t of the body, it’s of the mind.” Every interaction is an opportunity to gain knowledge. “I ask old people all the time, tell me what you know. It’s a trick you really need to know. I’m always like, hey Uber driver who’s 75 years old, tell me what your tips on marriage are, tell me about this – it’s just short cuts, research. Not everything is in books.”

A TV show is just the beginning of Adesuwa’s ambitions for a different vision of Africa. “It’s so crazy, because all of our history is recorded orally, most of the books you see are written by a white man, so it’s a skewed history.” Like Israel has the Birthright programme that supports the youth of the Jewish diaspora visiting the country on heritage trips, she wants something similar for Africa. Her idea is that in exchange for returning for the continent and experiencing it, youth of the African diaspora will collect histories from the countries and put that into books. She’s not stopping there though. “I want to have a summit with all the coolest Africans from around the world, I want people to come together – everyone thinks they’re alone – but I want to bring everyone together and make a plan and help our continent. There’s no reason for an African person to be in London working as an Uber driver when they have a doctor’s degree.”

There is so much determination in Adesuwa to call time on narrow-mindedness, on inequality, to find the good bits in life and expand them into a force for better. She might be the girl of the moment, but she is sure to leave a permanent mark with her life. In 60 years from now, Adesuwa will have the face of a woman who has really lived.

Credits

Photography Oliver Hadlee Pearch

Styling Carlos Nazario