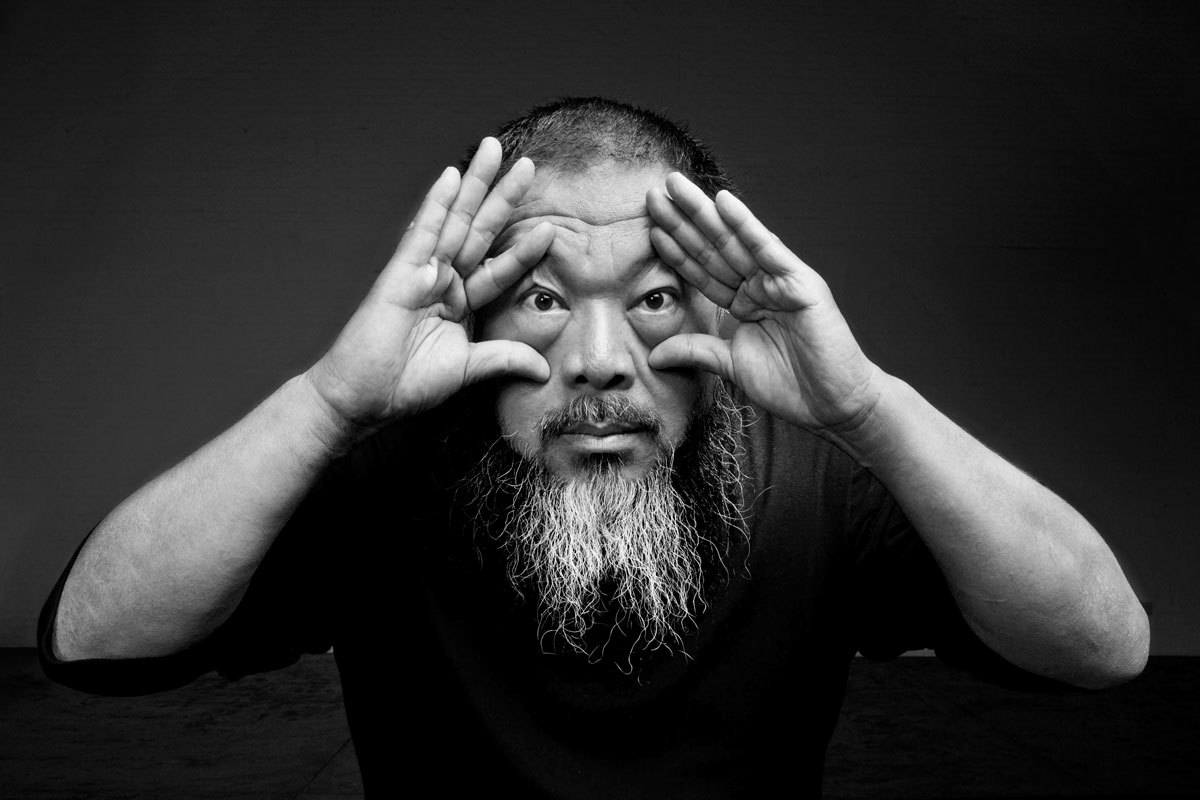

Ai Weiwei seems to be have been everywhere this year. For a man approaching 60, he’s got a drive that would make someone half his age pray for a break; “no holidays, no vacations, no weekends,” he laughs. He’s in New York right now, in the process of mounting an impressive four new exhibitions of work, across four galleries. It’s a city he lived in for much of the 80s when he was a student at Parsons and just emerging as an artist. “New York is a city I loved,” he states, about returning to a city that holds so much history for him, “And it’s hard to see again a girlfriend you have loved before.”

Four shows in four galleries in one city is a big enough project, you might think, enough to keep anyone busy. But Ai has mounted something like 15 large museum shows and retrospectives this year, made documentaries, been a tireless activist for the plight of refugees, a social campaigner, and, to top it all off, he’s writing a book that will cover “100 years of Chinese politics and culture.” The work will bridge his father’s generation — a poet who was sent into internal exile in the late 50s, suspected of being anti-communist — and Ai’s.

Quite an itinerary, but you sense there’s an urgency in everything Ai is involved in at the moment. You sense he’s got a feeling that he’s needed right now — that the world is in such a perilous state that it takes someone of Ai’s courage, visceral artistic ambition, and of course celebrity, to draw attention to the problems facing humanity. “I don’t guarantee to have an answer,” he suggests, of the problems his work confronts. “But I can at least pose a question.”

It hasn’t been easy for him to stick his head over the parapet and unveil himself to the slings and arrows of public opinion. His politically motivated detention by the Chinese government in 2011 turned him into a cause celebre for freedom of artistic speech; but, at times, the way he’s drawn attention to the failings of European politics in the wake of the migrant crisis has drawn a backlash. “I’m never trying to make work to please anybody,” he states, bluntly, of the criticisms he’s faced. “If I wanted to please people I wouldn’t be an artist.”

After he finally got his passport back from the Chinese government this year, he’s been free to travel, opening up his work to a world audience. It’s brought on this daunting world tour of exhibitions, art, and documentary making. He’s spent a year researching, hearing stories, spending time in refugee camps, documenting the migrants themselves, letting them recount their tales. He seems determined to break down the barriers of what art can be. “I’m trying to create something that can be more relevant to our lives than art,” is his opinion. To this end, the work touches equally on documentary, as it does more traditional artistic forms, or the sculptural works he’s most famous for (two of the shows in New York are dedicated to exploring his fascination with the tree as a symbol of rootedness, uprootedness, home, place, man’s relationship to the earth). He’s been chiseling away all year at finding the appropriate artistic language to present the emotional devastation of the refugee crisis, and the work unveiled at Jeffrey Deitch’s newly reopened New York gallery space is the one that hits you right in the gut. It is the work you feel — that will come to define this turbulent political era.

Titled The Laundromat the show is awe inspiring, shocking, heartbreaking. The gallery is totally devoted to the ephemera Ai has collected from an abandoned refugee encampment at Idomeni on the Greek-Macedonian border. After the camp was abandoned Ai painstakingly collected thousands shoes, worn over thousands of miles, thousands of items of clothes, scarves, coats, shirts. He then cleaned, washed, pressed them, represented them in the gallery, categorized and itemized them — children’s jackets here, men’s underwear here, women’s blouses here, rows and rows of shoes organized by size. Some shoes are missing their partners. The only immediate concession of the tragedy — the stories, the journeys — lurks within these clothes and haunts them. The scale is crushing and draining.

If previous attempts by the artist to feel his way into an emotional artistic possibility with the crisis have been conscious-raising — if not entirely (artistically) successful — this is the work that succinctly and powerfully encapsulates everything he’s been trying to do. Here, within the gallery, Ai grapples with the impossible weight and the unimaginable enormity of the crisis. He reduces it to simple gesture; lets humanity speak for itself.

Hello, how are you?

I’m good, thank you. It’s a nice day in New York, a lot of sunshine.

What’s it like being back in New York working on these exhibitions? How much has it changed since the 80s when you lived there?

It hasn’t changed too much, the city looks the same. New York is like a piece of rock that’s already been sculpted, it’s hard to add anything new to it. But today and the 80s are two different worlds; globalization and the internet have changed everything forever. Young people today have access to so much more knowledge and information, and I think that shows on people’s faces, it shows in the way people move. It’s not only New York, it’s London, it’s every city, every town, the world has changed.

You were in America for the election. It’s an interesting place for you to turn up in, at this time, with these four shows?

It’s a phenomenon. Everyone I know and speak to feels very frustrated by what is going on; today’s politics is very much like watching Tom and Jerry. Every bit of this truly reflects American democracy and culture; it’s all about personality and character. People vote for who they like, who they trust. But what do they trust? What are they going to do? People don’t care about the issues, but rather what neighbor they would like to live with.

There are four shows that have just opened in New York. Two utilize the tree motif, another deals with the refugee crisis. Do you see all four exhibitions as being interconnected?

Yes, it’s quite connected. The shows can be seen as different layers of the same work, or as one body maybe, although they are in different galleries. All of my shows have to relate to my current situation, and so a lot of these works relate to migrant crisis in Europe, the refugee crisis. I feel that every show I do needs to carry some message about my involvement in that. Every show needs to generate understanding about why I’m focused on the crisis, and why I care about it. So I’m very happy to have one exhibition devoted to that in New York, at Jeffrey Deitch’s space.

How different is the reaction to the work that deals with the refugee crisis in New York to Europe? Are people as aware of the problem?

In the US there isn’t the urgency, but people express their support and their appreciation, and say how they want me to continue to do this work. I think it’s a message that can resonate everywhere though, in Europe, in Mexico, in Africa, in the Middle East, and in the United States. The internet allows us to form a community, to get involved, to share ideas, express feelings, and share knowledge.

There have been very negative reactions, as well as very positive reactions, to the work you’ve been doing that deals with the refugee crisis. Has the reaction shocked you at all?

Of course any work that is meaningful will generate criticism, because for me a work needs to be a manifesto. I’m never trying to make work to please anybody. If I wanted to please people I wouldn’t be an artist. I’m not trying to be a pleasant artist, my work isn’t cosmetic. I do surgery, it’s like taking the heart out, which will never be pleasant.

I think most people are quite detached. Even if you have an opinion — and today it is very easy to have an opinion — it’s harder to get people involved. So I think the language of my work needs to be more about how we challenge things, asking people if they are willing to challenge things. That is why I appreciate any argument or criticism, because that means my work has led to people questioning things, or made people uncomfortable.

Is it the reactions that come out of your work that makes it successful?

Yes, that’s true. Take as an example my relationship with the China, especially the Chinese Secret Police. It is because of them I became the Ai Weiwei I am today. When I was in prison, I told them that I will never become like you, but it is you who make my voice relevant. Their opposition to my work makes it powerful in a way I could never have even imagined. There are certain forms and certain gestures these conservative powers cannot accept; but we need to always ask why can’t they accept freedom? Why does freedom scare them?

On a more formal, artistic, level — and I’m thinking more specifically about the show at Deitch here, where you’ve washed, ironed, cleaned the leftover remains of a refugee camp in Greece — what’s the process behind making this work? How does it go from conception to inception?

The work is about human catastrophe, and it’s also about how to present these emotions to people — how to find a visual language, as an artist, that can connect to our human feelings about disaster, ruins, war. How art can create a different rationality of daily life.

So the clothes of the refugees have been abandoned. These are clothes they left their homes with, the clothes of their children, the clothes that kept their elderly warm in the boats that they crossed the sea in. These are shoes they’ve worn for thousands of miles. They wore these clothes in the camps, without being able to wash their clothes or even to take a shower, living in the mud, in these tents. Nothing can represent that reality.

I am just picking up the fragments. I wash them, dry them, and iron them. I make them clean and hang them up. The exhibition is like going to any laundromat, or a department store maybe, the idea is to make it relatable to anybody. That’s a privilege and something I can do.

Your work on the refugee crisis moves between the documentary and sculptural and conceptual. Do these two different strands relate at all? Or are they simply different aspects of your art practice?

Art practice isn’t the right word. The right metaphor, I think, is of the journey, or climbing a mountain. You do anything necessary to move forwards, to make the next step, but you move on. And after you move on, the mountain is different, you don’t repeat the act. Each day is different on my journey. My determination is very clear, but besides that, I don’t know if anything good comes out of it; I don’t really care. I just feel it is a journey I have to take.

Is it interesting to think of the work within a tradition of art though? They are sculptural objects, but they are also much bigger and more important than simply an art object.

I’m trying to create something that can be more relevant to our lives than art. We live in such an extraordinary time; across the whole world the internet and technology have changed everything more than any over movement in history. Our future is becoming more and more unpredictable. The establishment, democracy, the western world, is changing. From Brexit to the upcoming US election, everywhere, everything is on the verge of changing. The old system is confronting new possibilities every day.

But art is so relevant to our struggle as human beings, it allows us be compatible, to speak a similar language, to understand. It’s a challenge for artists to create works that can do this, but I’m willing to take up this challenge. I could fail. People can see me as a joke if they want, but that’s fine, too. I don’t guarantee to have an answer, but I can at least pose a question.

What was it like working with Jeffrey on this exhibition?

Jeffrey Deitch has been very supportive. He liked the idea very much. We’ve been trying to do a show in New York for a long time now, but I resisted, New York is a city I loved and I only wanted to do a show that felt relevant; it is hard to see a girlfriend you have loved before. So this is something I’ve struggled with, presenting something that felt true.

How long a process was it to put the exhibition together?

Well he’s been asking for years. But the actual process is not too long, we’re always preparing new works, waiting until the moment is right, waiting for the right venue, the right location, then we strike. It cannot be graceful if it is too prepared. It’s like tip of an iceberg, you don’t need to see much to see the weight is there.

Well you have had a very busy year. You’ve had retrospectives in London, Florence; you’ve worked in Berlin, in Greece, all over the world. You’ve made documentaries…

Yes it’s true. I’ve done something like 10 to 15 museum shows this year. Then I’ve been making this documentary. I’ve travelled all across the world, across many nations, to make it. And then I’m also writing my book. This is the majority of my time. My art presentation is maybe one third of my time. Yet I still managed to do all these shows, I work around the clock, I have no vacations, no holidays, no weekends.

So what’s this book you are working on?

I’ve been working on it for the last two years, it’s a book about mine and my father’s generations, about the last 100 years of China’s cultural and political changes. I write in Chinese, but it will be translated into and published in English. It’s such a pity that it will never be published China.

Do you think your problems with China will ever be settled?

I still have a studio there, but I have a fundamental problem with China, one which might never be resolved. It’s about freedom of speech, about civil society, how to make it a better place for 1.3 billion people. I’m lucky to have not been put in jail permanently, and to still have a chance to get my voice out.

The tree is kind of a symbol for your relationship with China, right? This idea of rootedness, of uprootedness.

Yes, but it’s also about man’s relationship to earth, to this planet, the environment. For example, because of humans, there are areas of China that are now just desert, places with no trees, where not even grass can grow. I’m fascinated by this. These are spaces of human struggle against nature, because, of course, trees take hundreds of years to become trees like that; it takes rain, sunshine, wind, to create the form of the tree. But then in northern China, where you cannot find even one single big tree, it’s such a devastating situation. The trees I use are remnants found in mountain ranges or at the bottom of lakes. They are not from today.

Do you feel that art can change the world? Does the artist have an obligation to try?

I definitely think my art has to be relevant to my life and it has to reflect my knowledge, my understanding of our time. And that will change the world because it changes me, and I am part of the world. I first have to be honest about my feelings, if a work changes me, then it is already successful. Of course it may never change other people, but it is not my purpose to change other people, all I can do is try to encourage people to come out of seeing my exhibitions with their own answers. If I leave one clear mark on someone, I’ve succeeded. I don’t ask for more.

Credits

Text Felix Petty