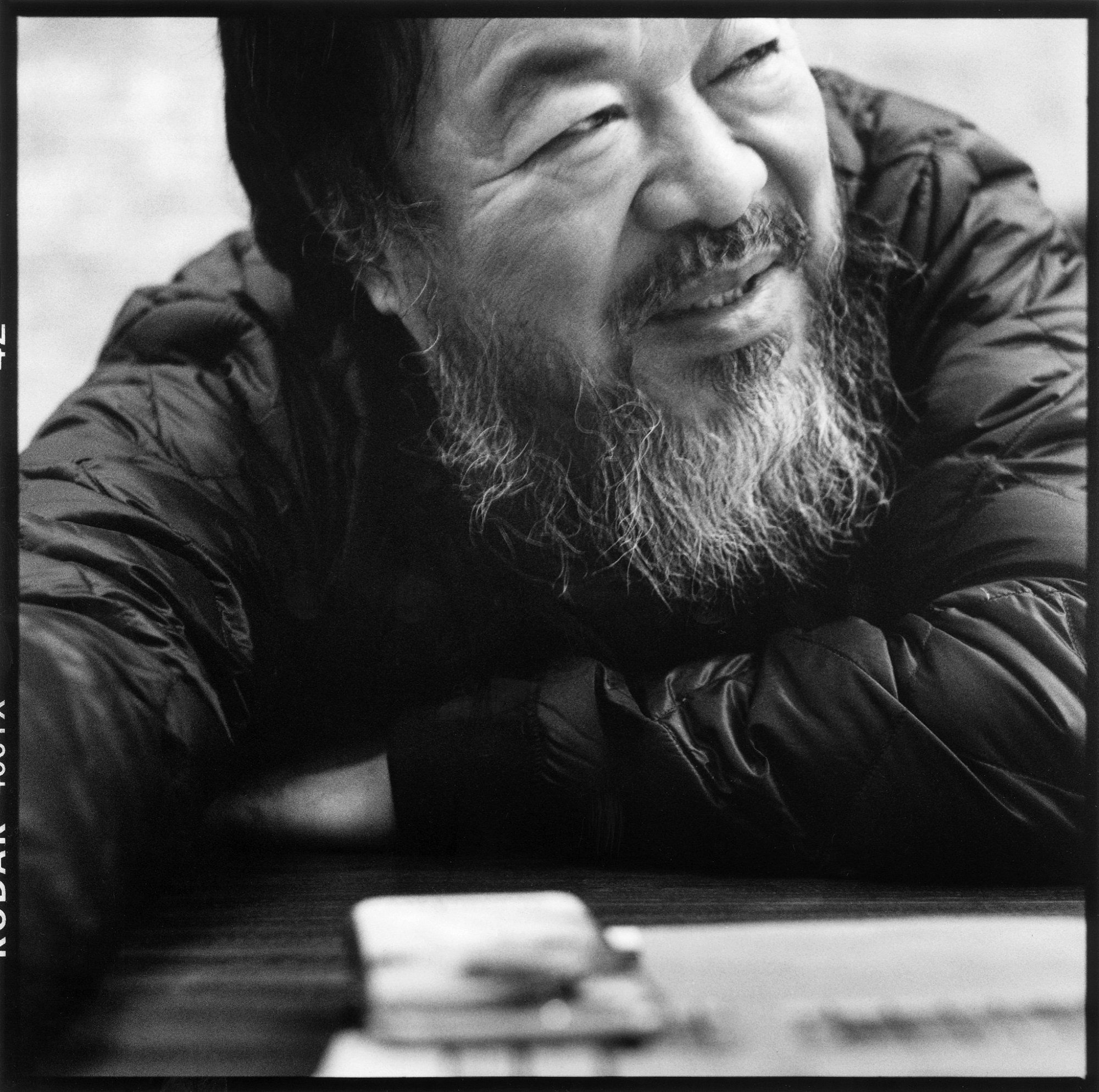

“Activist, architect, curator, filmmaker, even sometimes a pop star,” these are just a few of the descriptors used to introduce “the most widely known artist in the world,” Ai Weiwei, at the Brooklyn Museum on Saturday. He was there for a Q&A with fellow artist and Cuban activist Tania Bruguera, marking his first trip to New York since being detained by the Chinese government in 2011 and spending the subsequent four years under house arrest. It turns out there’s one title the dissident doesn’t take kindly to, however, and that’s “political artist.”

After being commended by an audience member for the bravery of his work, Weiwei smiled slyly, saying, “I never call myself a political artist, somebody calls me that, I think it’s an insult, but I accept it.” When pressed by Bruguera to explain, he said, “Every art has to be political. If it’s not political, it’s not art.” As he said earlier that afternoon, “To be a so-called political artist is first of all to be human. Surviving is political.”

Spoken like a man who has rebellion in his blood. The son of a poet who was “sent into exile for years,” Weiwei laughed saying, “In my life, I’m never negotiating with the art world, not a gallery, not a museum […] this is what I do, take it or not.” Similarly, he refuses to compromise with his own government. He spoke about Flowers for Freedom, a piece for which he placed bouquets in the basket of a bike outside his studio every day for two years as “a celebration of [his] impossibility to move,” before finally having his passport returned in 2015. The artist said of this silent act of protest that turned into a global movement, “I think this became very disturbing for the authorities. They cannot really stop this kind of action because there’s no clear reason for them to stop.” So when he was asked to put an end to it by his captors, he refused, adding that you can always win these types of negotiations because “they know if they stop you, it will generate something else which will be even worse than this.” He continued, “people always have big ideas, but they forget to do very small things which can relate to everybody.”

About halfway through their talk, Weiwei even refused to cooperate with his interlocutor after a question about his recreation of a haunting image of the drowned three-year-old Syrian refugee Alan Kurdi. After being asked about the backlash he received against the photo he said, “I don’t react to them, my only position is, let them react to me.” Bruguera continued, asking about an artist’s responsibility when intervening in situations that are not their own, to which Weiwei replied, “I’m an artist, I’m not a priest. I’m not necessarily saying whether my act will be right or wrong. I raise questions, I put myself into those questions, and if I cared like everyone else cared I would have never become an artist. I’m different and I’ll always be different,” and in regards to this image in particular, “I don’t give a damn shit about it,” he concluded. “It’s an image, we have much, much worse images in the world, we can always accept it. Just take it, or fuck it.”

New Yorkers will have the opportunity to do just that next month, when four simultaneous exhibitions of Weiwei’s work open in the city, at Lisson Gallery and Deitch Projects, and two at Mary Boone.

Credits

Text Emily Kirkpatrick

Photography Alfred Weidinger via Flickr