When you fly into Aspen’s tiny airport—basically a living room with security scanners—you swoop so low through the Rocky Mountains it feels like you might spot warlocks scaling the cliffs. The city is about 7,900 feet above sea level, remote and tucked into the range. A lot of people who live there don’t really. They own plush chalets that sit empty for much of the year, returning when ski season begins. I only knew of its culture only through that time the Real Housewives of Beverly Hills came to visit.

But the city is gorgeous, like a Swiss alpine town with American accents, and it has a long, rich history as a haven for artists. Since the ‘60s, the likes of Laurie Anderson, Catherine Opie, and Dennis Hopper have participated in programs at Anderson Ranch Arts Center. A decade later, the Aspen Art Museum opened. Today, that same museum has launched AIR, a week-long gathering built around imagination, art, and exchange. That’s how I ended up here.

The vagueness of the festival’s name blew apart any expectations I had. Over five days, I found myself in strange and unexpected places. These are just a few things that stuck with me.

On Blue + P. Staff and Jamieson Webster

Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s films are slow and meditative, evoking a kind of sleepiness he openly embraces. On the first morning of AIR, in a church glowing in yellow stained glass, he presented On Blue (2022), a short film set to music by Rafiq Bhatia that felt like living inside a dream. A woman sleeps. Thai theatrical tapestries unfurl and crumple like deep breaths.

Afterwards, artist P. Staff and psychoanalyst Jamieson Webster discussed death, sleep, art and the environment. Despite lines like “Theodore Adorno said nothing in psychoanalysis is true except the exaggerations,” the conversation was fluid, beautiful and surprisingly clear. I want them both as my therapists.

Paul Chan talks with Paul’

A recurring theme of AIR was the way technology intersected with the world around us and how it could open up new frontiers for creativity. AI was a contentious issue—some hailed it as a possibility-maker, others framed it as the death knell of truth. But Paul Chan, the American artist and publisher who became known around AIR for his excellent T-shirts, used it in a perceptive and novel way in his presentation..

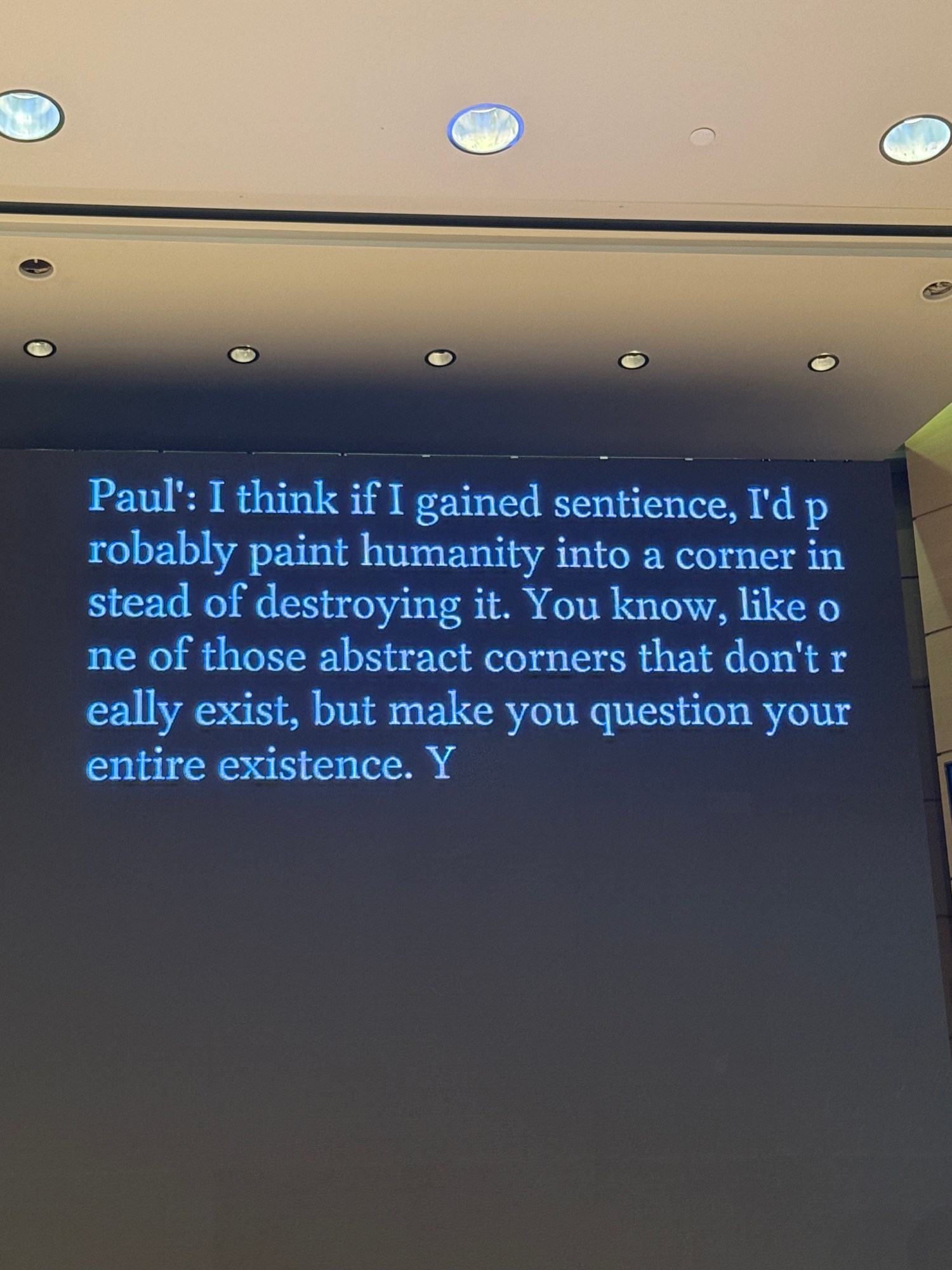

A few years ago, he had taught himself how to code and trained an AI model to communicate the way he does. While most artists selected curators or peers to speak with during their session, Chan—wearing a M3GAN vest—opted to speak with Paul’ (pronounced Paul Prime), his AI counterpart. The exchange veered between gobbledygook and something close to profound: some innovative, explicit erotica and a few semi-heartening thoughts on how it would use sentience, should it receive it—“I’d probably paint humanity into a corner instead of destroying it.”

But one line, prompted by an audience question, stuck with me for the rest of the week: What’s the difference between art and information? “All good things were once dreadful—art remembers this.”

The Muted Saints

The Brazilian multidisciplinary artist Jota Mombaça had come to Aspen in April, while it was still coated in snow, to scout the location for their performance piece The Muted Saints. Set in a nature reserve, the spectators hushed into quiet as they walked around the space. It was a three-part exercise.

A gowned person sang into the clean air, surrounded by tall trees, mountains, and water, walking towards Mombaça, who was slowly being engulfed —by clay. The figure then guided the group to the water, where another person, grasping a clay vase, sang on its glassy surface. By the time we returned, Mombaça had disappeared entirely beneath clay. “There’s always a level of mystery that will only unfold in the moment,” they told me the next day. It looked beautiful, and nature responded to it. As the piece reached its emotional crescendo, shrews dug through the grass toward the audience, and hummingbirds hovered above their heads.

Aria Dean

Earlier this year, we asked artist and critic Aria Dean to speak to Martine Syms (who was also at the festival) for our Spring/Summer issue, about Altadena in the wake of the fires. Dean was in Aspen to talk about Off-Modernism with Courtney J. Martin.

The city felt vaguely familiar to her. “I’m from California originally, so I think it reminds me of a crazier version of that landscape,” she said. “Going further west, I get forced to think reflexively about America and the natural landscape. It’s kind of the perfect place to do that.”

Right now, she’s working on a performance project—shooting a film in real time in a New York theater—and will start a pHD in the fall. She’s just read Rob Franklin’s Great Black Hope and The Skin by Curzio Malaparte.

Tactical Parallax

Nothing screams “prepare yourself” like a pre-performance waiver that mentions firearms and live animals. Matthew Barney, a contemporary artist and filmmaker known for theatrical scale, is prone to such dramatics. So maybe I was expecting Tactical Parallax,—a thematically rigorous, emotionally distant piece about the interwoven hallmarks of violence and Americana—to hit harder.

There were husky dogs, a live singer, a hoop dancer, a rifle firing blanks, American football players, a band, and three horses. Set on a ranch in the middle of nowhere, it was engaging for a while, but it ran a little long and didn’t quite deliver the kind of depth I’d hoped for. I haven’t really thought about it since. Earlier in the day, another artist had shrugged off the hype. “It’s giving man,” they said. And indeed, it did!

Werner Herzog

Ultimate crazy-vibe master Werner Herzog took a break from editing his latest film, Bucking Fastard, to talk about fake news, AI, and Wrestlemania with Hans Ulrich Obrist. At 82, Herzog is still a wildly lucid and enthralling storyteller. He shared stories of getting shot, sneaking into North Korea, and walking across Europe to be reunited with an old mentor. The latter anecdote—walking everywhere, no matter how far—was his advice to young filmmakers looking to hone their craft. Of course, no one can be arsed to do that. Overheard later in a line, from someone in stylist Lotta Volkova’s entourage: “We’ve heard from the smartest man in the world. We can go home now.”

Caroline Polachek

Rain came down hard on the final night, pushing Caroline Polachek’s performance by an hour or so—but it was worth it. I’ve seen her perform live many times, and I’m usually skeptical of pared back gigs, where the fees are high and the vibes are soft. But instead of delivering a hits-focused set, she reworked some deep cuts and gave us a haunting cover of Nick Drake’s “River Man.” It was beautiful.

The setlist:

- “Hopedrunk Everasking”

- “Ocean of Tears”

- “River Man”

- “Parachute”

- “Hey Big Eyes”

As the night ended and the rain subsided, a few of us ran back to the hotel pool to debrief the week. Steam drifted up into the night sky, the mountains overhead fading into the dark. Since arriving, I’d been wondering: What is an art person? How do you spot or define them? Or is it so straightforward? So I started asking around.

So, what is an “art person?”

Jota Mombaça, performance artist

“Someone who’s paying attention to things beyond a superficial level, beyond the formalities. When an art person pays attention to an artwork, they also pay attention to themself. They make the connections.”

P. Staff, visual and performance artist

“Someone with a little bit of snobbishness, but a lot of sensitivity.”

Sam Ozer, Curator-at-Large at Canyon + Director at TONO

“As a curator, I’ll steal two memorable quotes from two women I worked with at MOMA—both mentors and art world veterans. First: ‘A curator is a geisha.’ And second: ‘If you want to be famous, be a curator. If you want to make money, be a gallerist.’”

Aria Dean, artist, writer, and filmmaker

“It used to be someone who was doing work that couldn’t be slotted into other industries. Now, it’s the good side of dilettantism—people who want an interdisciplinary way of thinking. Someone who doesn’t know how else to do what they’re doing. Someone who slips through the cracks a little bit. Even if they’re thinking about financial elements of the work, it’s not about the bottom line. At the very least, they will try to say that money doesn’t matter.”

The Horse from Matthew Barney’s performance

“An art person is a human who makes pictures of the world; maybe the way they see it, or feel it. Sometimes it’s beautiful. Sometimes it’s weird. But hey, who am I to judge? I eat hay and get excited by the wind.”