In the summer of 2013, knitwear designer Aisling Camps was crying her eyes out on a plane headed back to Trinidad. The flight felt like the tragic end to nearly a decade of tireless work she put in to make it in New York City. She’d earned a degree in engineering from Columbia and a degree in knitwear design from the Fashion Institute of Technology. She’d spent countless hours assisting runway productions at Fashion Week and interned for a number of top brands. But despite all her achievements, her time was up. Her failure to secure the rare fashion job that sponsors a work VISA meant she had to voluntarily return back to her parents’ home in the Caribbean or face deportation.

Even though she was only 27 at the time, the move felt like a defeat she’d never get over. “I was really depressed,” the designer explained to me, as we talked about adjusting to life with her folks in the Tropics after nearly a decade of working and studying in the US. “I lost a lot of weight and looked like one of those alien chicks—a big praying mantis.” But being outside of the New York fashion bubble helped her get grounded, too. “No one tells you you’re being an asshole in New York,” she said to me. “Being home was a good reset button to humanize me and get back to what’s important.”

And what was important to her was design. She’d brought back to Trinidad two large knitting machines that she had purchased from a professor at FIT for $800-a-piece. In her parent’s home she built her own design studio and decided to launch her eponymous brand since no one in the States would sponsor her. “Because I didn’t have the most robust social life in Trinidad, I kind of locked myself away and worked like a beast,” she said. “There was an exponential growth in my fluency [with making knits] because I was isolated and I had nothing else to do.”

The first knit garment Camps produced in the studio at her parents house was a cream and mint crop top comprised of cotton knit and nylon yarn with a faux cut under the boob, boasting short row intarsia and ottoman stitches. But more than the ambitious styles she used to make the top, what set it apart was that it was that it was effortlessly sexy. This became the template for her approach to knitwear design. “People think about Midol and English Breakfast tea when they think of knits,” she said. “Fuck that, man. [I’m] trying to make knits cool.”

It didn’t take long before Camps had established her brand in Trinidad, offering a full range of knitwear designs that worked for the climate of the Tropics. She used materials like bamboo yarn and took color inspiration from places like the Grand Riviere, a lush remote village in Trinidad. She was covered extensively by local blogs and hosted pop-ups at Meiling, one of Trinidad’s top fashion stores.

“I was really getting comfortable with the idea of being in Trinidad,” she told me. She had made new best friends, found a new boyfriend, and her business was on the verge of really expanding. “I was going to buy all these knitting machines and train students to use the machines. I was going to have a sweatshop [Laughs].”

And then everything changed, again. In the spring of April 2014, after trying four years in a row, Camps won the lottery—the green card lottery. “I didn’t tell anyone for two days because I was just confused,” she said. “Part of me was mad. It was kind of surreal.”

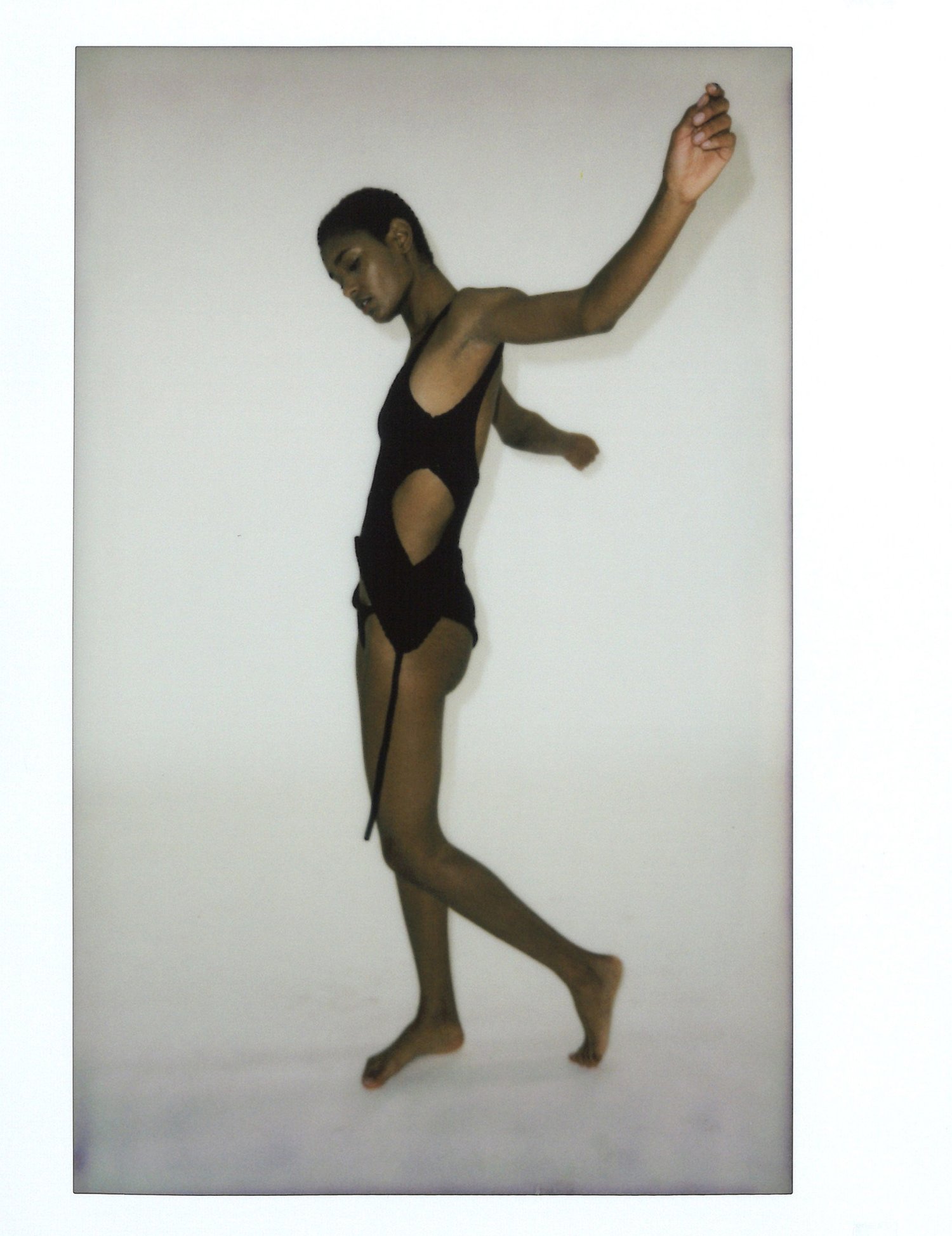

Upon her triumphant return to New York City, she has taken the Aisling Camps label to new heights. Stars like Cardi B and Janelle Monae have slayed in her layered knit wares, which match the comfort of pillowy yarns with the raciness of cutouts and plunging backs. And while she still makes many of her garments by hand on her machines, she’s moved some of her production to Italy to keep up with demand. And that demand has only ticked since she sent an oversized chunky knit down the runway at Pyer Moss’s fall/winter 2018 presentation.

Right now, she’s in the process of relaunching her namesake brand with what she considers to be “collection zero.” I got to take a look at the range at her home studio in Crown Heights, which has everything from mesh tank tops to a three-piece knitted suit.

Aisling Camps’s home is consumed by her art: Hulking metal knitting machines dominated her living room. Stylish moodboard images wrapped her walls. And her latest collection of light knitted three-piece suits and gauzy see-through tops loomed on a big rack in her bedroom.

She showed me her process and told me about her trials and tribulations as a burgeoning designer, her new direction for the brand, and what it means to be a black designer in NYC right now with an immigrant background. Here’s what she had to say:

In the States, there is a lot of talk about “black designers” right now. But race is seen a bit different in the Caribbean. What do you identify as?

I was born in Port Au Spain Trinidad. My great grandmother on my father’s side was from Madeira, Portugal. And my mom is Spanish, native Carib, and black. I know where I’m at, and I understand the history of this country, so when I’m here, I identify as a black woman. But when I’m in Trinidad, I’m what they call a “red girl,” which is mixed. In the Caribbean, there is more colorism than racism. Here, if you have an ounce of black in you, you’re black.

Your sense of design seems so intuitive. Are your parents fashionable?

My mom is the embodiment of a peacock. She will get dressed to the nines every morning to go to work. I just remember going to Paris when I was 11 and my mom buying these crazy jacquard pants that were neon orange and pink. I wonder if she still has them, cause I would steal them. [ Laughs] She just has an innate way of mixing and matching colors and patterns. She doesn’t play by any rules.

Do you think you also get some of your style from the Caribbean?

Back home, you don’t have a wealth of choice. There’s no Zara or anything like that. You have to have something made or go shopping abroad. So there’s more of a thrifters approach to clothing. People just make things work.

Do you think you took a “make it work” approach to launching your own brand?

Yeah, this whole thing started because I got kicked out of the States and I had to go back home. In Trinidad, I couldn’t get amazing fabrics because there is limited access to everything. Even though I can do wovens, I went straight into knits so that I could control my fabric production. I would order the yarn direct from places I knew had good quality. I made it work.

How’d you even start designing, considering your first degree was in engineering?

It’s kind of cruel for people to ask 16 years olds what they want to do for the rest of their life. I always did a combination of science and art in school. Even when I was studying engineering, I took lithograph and oil painting and advance drawing. After I got my engineering degree from Columbia, I worked for a firm across the street from FIT. My supervisor at the firm was abusive. She would throw me under the bus for stuff. I had to get out. So I gave myself six months to apply to fashion school and save up enough to pay the tuition.

What was it like learning about knits at FIT?

I had a terrible first teacher of knits. She was like an evil catwoman. She would yell at you and be like, “There’s nothing wrong with the machine, there’s something wrong with the knitter.” She was always mean. So, I was like “Fuck this. I don’t want to deal with mean cat lady people.” But I got really really pragmatic and saw knitting as a tool to get a job, because knit designers can design wovens, but woven designers can’t design knits.

It still didn’t help though, huh?

I went on so many interviews. I met with job hunters. I got a call back from Zara. But I still couldn’t stay. So I moved back into my parent’s house at the age of 27 and got really depressed. It was a huge shift because I’d never been an adult in Trinidad. But in hindsight, being home was a good reset button.

When you came back to the States, things got pretty lit. What was it like making the sweater that appeared in the Pyer Moss 2018 show?

I met Kerby at a bar in Bedstuy called Sincerely Tommy in like 2017. The first time he asked me to make something for one of his shows, the timeline was too tight and I didn’t want to disappoint him. When he hit me in 2018, he gave me an extra week. By then everything had changed, because I had a factory that was able to produce quick. So I bought a ticket and I went to Italy because I knew he was poised to take off. I wanted to give him a good shot by making him something special.

You’re in the process of re-launching your brand right now. What can you tell me about “collection zero”?

There are 20 designs. It’s really tight—not a lot of different color ways. I have some experiments in there, like a knitted three-piece suit. I still have slip dresses and layering sheer pieces. And I have made some crazy chunky sweaters that are like the cousins to the Pyer Moss sweater. This collection covers every season, so I’ll be pushing it all year.

You’ve overcome a lot of obstacles to get your brand where it is. Does your experience speak to the unique struggles blacks faced to make it in the industry?

You don’t see a lot of black designers succeed. You see them come up and you wait for them to do really well, but then it fizzles out. But that happens across the board. The reason it is harder for black designers is money and backing. At the end of the day, the average fashion brand is fronted by some ex-model or celebrity who doesn’t know about clothes but has cash and a following. The people who are the real makers usually don’t have a ton of money.

How do you ensure that your brand survives and doesn’t fizzle out?

I live off of what I sell. I’m trying to make this work, but the barriers to entry are absurd. It is an insurmountable amount money that is necessary to fuck with the big boys. I’m counting on the fact that I have talent and I’m stubborn. All the shit I’ve gone through must count for something. Once I decide I want something, it usually happens—just not when I want it to.