This article originally appeared in i-D’s The Superstar Issue, no. 354, Winter 2018

The world of Akwaeke Emezi’s extraordinary debut novel Freshwater is not a metaphor. It’s not even a literary construct. An original and affecting journey in which multiple realities answer multiple questions about identity and trauma, it’s the real life tale of a queer, trans, black, African, Nigerian writer as they attempt to navigate the occasionally odd sensation of being alive. “I’m writing a story in which this is the core reality,” says Akwaeke. “It’s not othered, it’s not superstition, it’s not magical realism. It’s true.”

Based, for the most part, on Akwaeke’s own experience, Freshwater tells the story of Ada, a young Nigerian woman who develops separate selves. Charting her experience as an ogbanje – a term from the traditional Igbo religion which describes a hostile spirit born into a human body – it sees two competing voices, Asughara and Saint Vincent, follow her from her home in Nigeria to college in North America. When Ada suffers a sexual assault at the hands of another student, the voices step forward, taking control and sending her life spiralling towards destruction.

“I didn’t think I was going to write Freshwater until maybe a couple of months before I started,” the 31-year-old Akwaeke says today. Akwaeke had actually planned to write a short story about a sex party in Lagos that “would have been much easier to do and probably much easier to sell.” It wasn’t until a friend encouraged them to do “this other really weird spiritual book that I was deeply uncomfortable with” that they made the decision to take the leap. “If you’re scared of something, there’s a reason; something in it that you need to run towards and not away from,” Akwaeke explains. “So I went back to Nigeria and I started talking to a couple of people who knew a bit more about the traditional Igbo religion.”

Akwaeke told them that they were working on a book, the premise being “if you’re the child of a deity, and you put a deity into a human mind, of course the mind is going to break because it’s not designed to accommodate that”. Raised Catholic, Akwaeke had always looked at life through the lens of Christianity, and tried to deal with their own plural spirit through a western mental health point of view; using therapy as a means of controlling the conversations in their head. However, speaking to people about the traditional Igbo religion, Akwaeke found for the first time that people understood exactly what it was they were experiencing. “It felt like all these things that didn’t make sense in my life had finally clicked into place.”

“Where do you put the people who are, quite literally, in some other world? Who are experiencing things that people don’t consider real? Who are seeing the future in their dreams?”

Akwaeke details how “if you’re existing in a reality that doesn’t look like what western mainstream reality looks like, you’re sick, you’re broken, you have to be fixed.” Viewed in an Igbo context, however, “I just got a lot of reassurance. I went back home and talked to people and told them that this is the pull that I’m feeling. I got a lot of courage from people who said that this book would be helpful because they too were experiencing realities that didn’t make sense with the lenses they were given.”

Of course, the battle now is ensuring that Freshwater is read in the context in which Akwaeke intended. Although rapturously reviewed, and currently longlisted for the Carnegie Medal of Excellence, numerous articles have continued to critique the book through the lens of mental health; the depression, loneliness, and self-harm that Ada experiences being symptoms of some dissociative identity disorder, rather than genuine embodiment. When pressed, Akwaeke likes to use a quote by the novelist Toni Morrison who, after winning the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1993, was asked what it was like to be accepted by the mainstream. “I stood at the border, stood at the edge and claimed it as central,” she said. “Claimed it as central, and let the rest of the world move over to where I was.” This is also what Akwaeke is doing with Freshwater – asking the reader to move themselves and find a different perspective, consider what life looks like lived in an indigenous faith tradition. Imploring them to accept that lens as a valid reality.

“I wrote the book specifically for people who are inhabiting marginalised realities because I realised that this is a thing that we’re not talking about,” Akwaeke continues. “We talk about marginalised people on different bases like gender and sexuality or race. But where do you put the people who are, quite literally, in some other world? Who are experiencing things that people don’t consider real? Who are seeing the future in their dreams? People like this existed before there were words for it in a western mental health context. We don’t have access to these histories anymore so I thought, yeah, I would write this little weird book and hopefully it will help some people.”

As for themself, Akwaeke is, today, mostly interested in what it’s like to be an embodied spirit in a contemporary context. They laugh about how friends will recognise when one of their other voices steps forward in the group Whatsapp and describe how the different selves are always shifting, with “whichever needs to come in front to perform function, coming forward.”

“We got colonised, and then after that the concept of ogbanje sort of became a myth, not something that’s real,” Akwaeke says. “Part of my work now is centering this reality, reclaiming it, and then asking, so what does it look like to be this kind of embodied spirit on social media? To have an Instagram account? To be on Twitter? To write a book and do press? What does it look like to be open about it in this day and age? That to me is the most interesting part. This book is just one part of a larger thing.” Or one voice in a wider plurality.

Credits

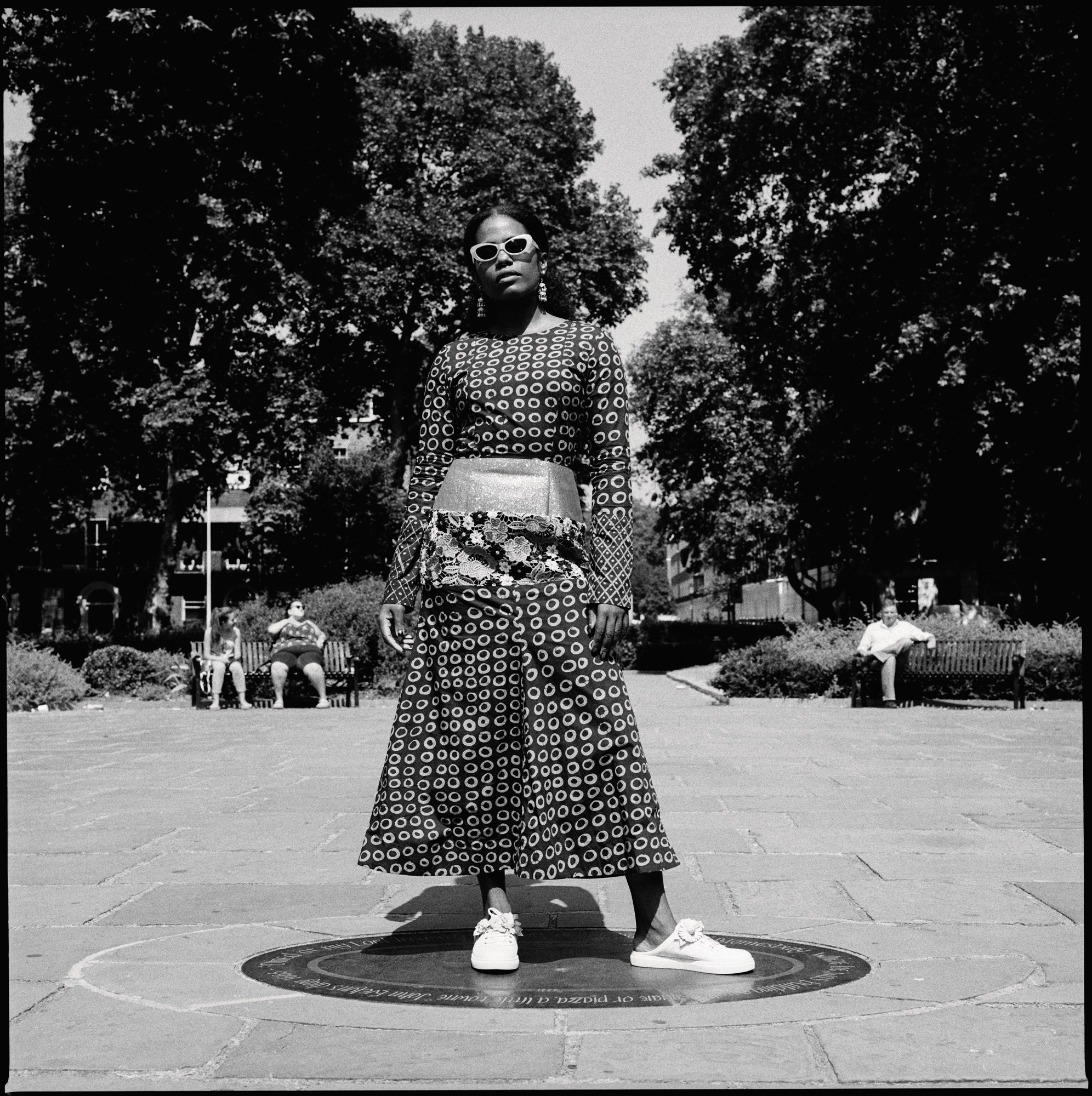

Photography Adama Jalloh

Special thanks to Rebecca Boyd-Wallis.