Photographer Alex Prager is one of today’s best visual arbiters: an artist whose skill at devising fantastical, cinematic snapshots has placed her in the legacy of contemporary photography greats—a stone’s throw away from Cindy Sherman, Gregory Crewdson, and William Eggleston. For the unfamiliar, the artist creates dreamy, meticulously designed mise en scènes—shots that place the viewer right smack in the middle of a frozen piece of action without any context. Take her series “Week-End” (2010): in one image we see a woman, clad in a floral dress and heavy eye-shadow, floating in a shallow puddle in an ambiguous landscape. There’s no hint as to why she’s there or what exactly she’s thinking, but the picture sparks a million possible ideas that ultimately go unanswered.

LA-based Prager is often viewed as a distinctly American artist. She regularly incorporates stylistic tropes from the golden era of Hollywood and mid-20th century fashion (we’re talking ladies with lots of red lipstick, noir-ish environments, old taxi cabs, toll booths) into a body of work that is more hypnotizing than simple pastiche. She makes the type of images that Matthew Weiner probably gets lost in when looking for inspiration. That doesn’t mean her work only resonates with an American audience, though.

This past month, Prager debuted her oeuvre for the first time in Turkey at Istanbul74, an annual arts and culture festival featuring international creatives in a three-day mélange of exhibitions, panels, and parties. At Prager’s opening, comprised mostly of her work from the series “Faces in the Crowd” (2013), I wasn’t sure if the Americana overload would resonate with a Turkish audience. It spoke lengths, however, when an Istanbul local pointed to a projection of the artist’s eponymous short film, and casually said, “I love Elizabeth Banks—she’s timeless!” in reference to the work’s star.

Later in the weekend, Prager eloquently explained that the relatability of her images are not culture-specific. “With my work, I try and leave enough of the story out so that it’s just a moment people can respond to however they want,” she told me over tea. “There’s a universal, human quality about it beyond American pop culture that engages with anyone’s personal experiential tract—the people they’ve known in their life, the art and culture they love, the emotions they’ve felt.”

Prager and I also chatted about why she pushes against visual artists who reject calling themselves “photographers,” and how even though she tries to control every aspect of the action in her stills, there’s always a bit of unpredictable human nature that bleeds into each frame.

Do you consider your practice photography, visual art, or another term?

A few years ago, I called myself an artist. Now, more and more, a lot of people seem to be rebelling against photography and are less and less interested in being a “photographer”—everyone wants to be called an “artist.” As a result, I’m starting to go back and appreciate photography again as a medium for exactly what it is. You can say it’s art—and of course it’s art—but as a medium, as a tool, it is photography. I consider myself a photographer and a filmmaker.

Photography is a fucking beautiful medium and I think it’s so cool and has such an interesting history to it. There are so many interesting, experimental things constantly happening with the technology. It’s so interesting to see where it’s going, but it sucks that a lot of people are pushing against the word ‘photography’ because it really is photography.

It’s really refreshing to hear you say that. I know a lot of your images are formatted or touched up in post, but do you still primarily use film cameras?

I only shoot with one camera and one lens. It’s a Contax 645 and I use Portra 400 film. It’s the best. Portra changed it recently—a year or two ago—and it’s not quite as good as it was. The colors aren’t quite the same. Everything got a bit crisper and the grain is a lot smaller. The colors are more realistic. They used to process a bit more yellow-y green, and now I have to bump up the colors in Photoshop more.

So you preferred it more when it was less realistic looking and a little more fucked up?

Yes! Definitely. That’s why you shoot in film, right? It has its own life to it.

I find that super interesting because a lot of your work involves these really planned out, large-scale scenes—visual narratives you’ve arranged. To hear you say that you appreciate when film has its own inherent imperfections feels like a distinction from your practice.

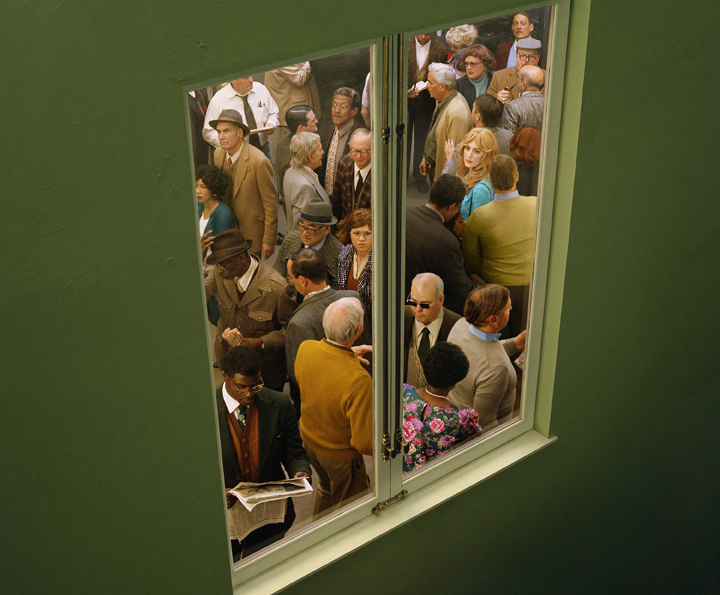

I meticulously stage everything, and I have so much control over every little detail, but it’s always the weird little mistakes that happen on set, or the things I didn’t plan for that happen, that make the photos more exciting for me. For example, there’s this one photo where you’re looking through a green wall with a window at a crowd—you know that photo?

Yes, I actually took a close-up photo of this one older guy in the top left corner whose eyes are bug-eyed.

Yes! That was literally what I was about to say. I did not tell him to do that. What the fuck is he doing? What is he looking at? When I saw that, I felt like I had struck gold. It was an imperfection because I had told everyone not to smile, be really in your own world, do your own thing, and then here’s this guy standing on his tippy-toes, looking at something and his eyes are bulging out of his head. What is going on here?

Even if you have everything planned out and fully conceptualized, life is still spontaneous and unpredictable.

Yes, exactly. You can try and control a crowd and do so many things—you can control the makeup, the wigs, the hair, the costumes, the lighting, the sets—but once you’re actually working with a real crowd of people, they bring their own emotions to set. Whatever was just happening to them beforehand, whatever traffic they were in, whoever they just broke up with, or just got married to, or their own experiential tract, that all comes with them to set. You can only control it to a certain point, and there’s always going to be a little bit of chaos.

Do you encourage multiple interpretations of your work?

Oh yeah, definitely. I try and leave enough of the story out so that it’s just a moment people can respond to however they want. And then again, the viewer’s personal experiential tract engages with the images—the people they’ve known in their life, their own art that they’ve loved. People love to relate things and find familiarities in other things.

What advice would you give a young photographer?Everyone finds his or her own process, and it’s not good advice, but there’s nothing I can say that’s going to make someone a good photographer. It’s more about shutting everything off, turning everything else off, except that feeling inside that tells you if you’re in love or not. How do you know when you’re in love? You know when there’s this overwhelming sensation of knowingness. It’s ineffable, but you just know. You can’t analyze why certain people fall in love with certain people. It’s the same feeling when you know you’ve got the shot, and you’re on the right track. It’s this feeling you have to keep following and making that stronger and stronger. The more you acknowledge that feeling, the louder it gets.

Credits

Text Zach Sokol

Photography Alex Prager, all images courtesy the artist