On a Thursday afternoon, Alvaro Barrington is slumped on a rattan bench at Tate Britain. It’s as if he’s been lulled by the sound of rain hitting the corrugated steel roof above us, as well as the ambient soundtrack that courses through the gallery space. And his outfit is similarly relaxed: a cosy sweater and tracksuit bottoms that complements his unassuming personality. “I think of myself as a very lazy artist, even though I work all the time,” he says cheerfully, sinking deeper into the chair. “I’ve learned to embrace every part of every moment because a lazy conversation may inspire something five years down the line.”

This openness was integral to Grace, Barrington’s three-section installation on display at Tate Britain’s Duveen Galleries until the end of January. For the show, supported by Bottega Veneta, the artist collaborated with over three dozen creatives including Jawara Alleyne, Dev Hynes and NTS’ Femi Adeyemi. “Painting can often be so much about just one person and the canvas, and so painters don’t necessarily know how to collaborate,” he says. “But I thought, ‘How does art show up in the Black community in a way that I understand?’ Even though I’m a painter, I see it through crocheting, braiding, multiple other ways.”

The corrugated roof, rain, music and benches reference Barrington’s childhood memories growing up at his grandmother’s house in Grenada. “My mom got pregnant with me when she was 17, and my grandma, like many grandmothers [in Grenada], was like ‘send him to me,’” he says. “That was something we took for granted in our community,” he says. “Everybody grew up with their grandma.”

In the North Gallery, a boarded-up kiosk has been made to American prison-cell dimensions, with church pews facing the sculpture. The work draws from the injustices committed against Black men in 80s and 90s America. “Kids would go to buy a bag of chips from the store, and cops would arrest everybody who was at the corner assuming you were selling drugs with them,” Barrington explains. “A lot of the women in the community turned to church because the system felt so impossible.”

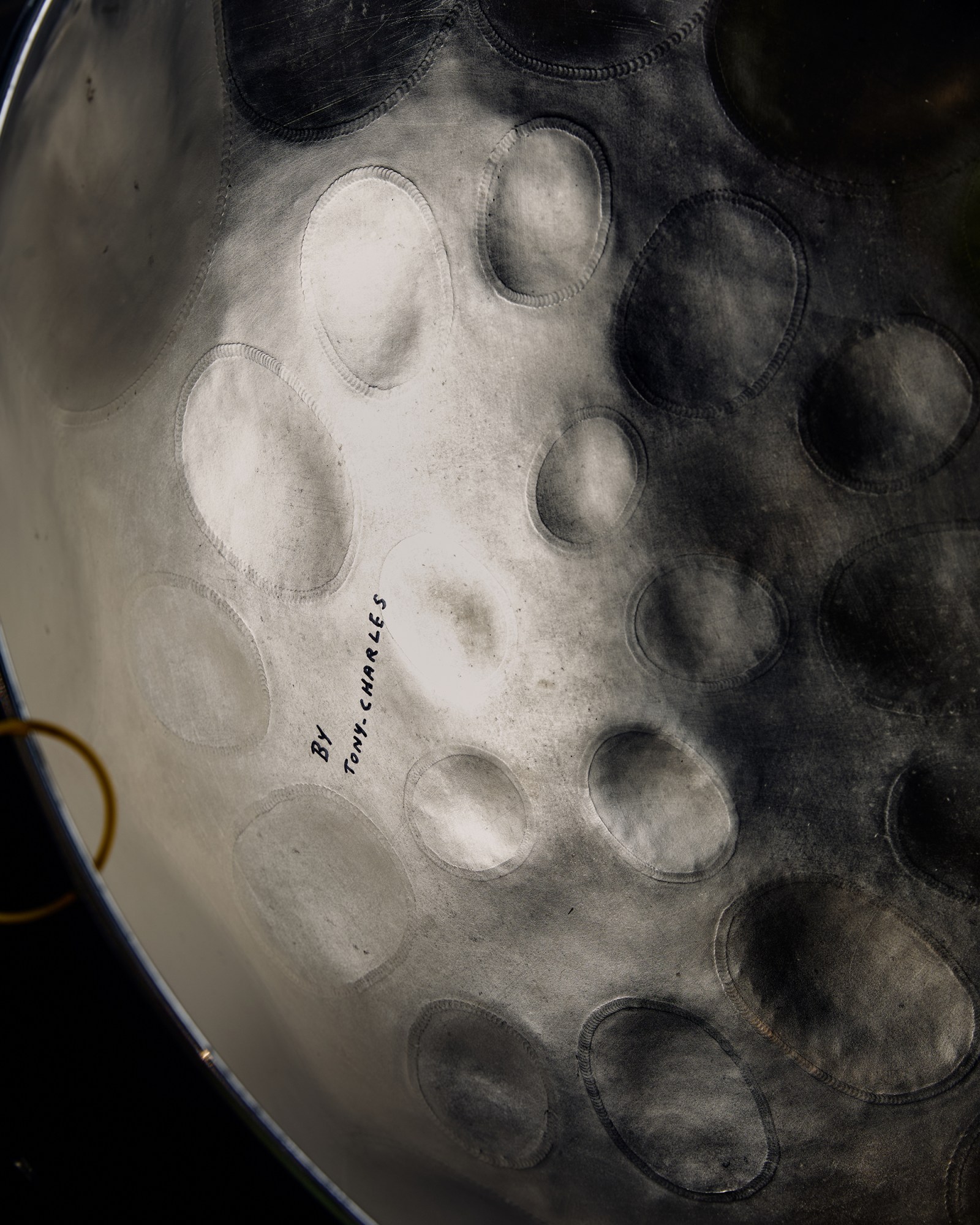

Yet most striking of all is the three-metre high figure in the central rotunda, depicting Barrington’s lifelong friend Samantha. She is dressed in carnival attire, designed by Alleyne, and dances among steelpans and paintings reminiscent of various carnival traditions. “It doesn’t happen in many other cultures that a man or a woman can be in a bikini dancing in public, and everybody knows that’s their space to engage with their body however they want to,” says Barrington.

Born in Venezuela and raised in Grenada and Brooklyn, Barrington moved to London in 2015 to undertake a Masters at the Slade School of Fine Art. Despite not considering himself British, “for half of my life, I’ve had the King or the Queen as my head of state,” he says. “So I thought, ‘What does that mean to me and how do I explore that relationship?’”

The gallery saw Barrington’s layered relationship to the UK as a strength. The Tate Britain’s senior curator of contemporary British art, Dominique Heyse-Moore, tells me that she has been interested in “how stretchy we can make that notion of what British art and a British artist is” since joining the gallery in 2022. She adds that his unconventional materials such as mirrors, steel drums and concrete slabs combine to create “an expanded painting practice that goes beyond the frame.” At one end of Duveen Galleries, Lady sing small @proud Mary bottom up (2022) stands at just over six feet tall, with coloured yarns forming geometric shapes over blue burlap and a broom dipped in concrete hangs the base of the piece.

“Painting is so much about just one person. I thought, ‘How does art show up in the Black community in a way that I understand?’”

The installation gains a sense of immersion through its multimedia works. Musicians, including Hynes and DJ Olukemi Lijadu, created pieces to accompany the rain viewers hear over an installation Barrington modelled on his grandmother’s house. More subtly, hair artist Taiba Akhuetie used various leather materials to create braided pieces to decorate four of the eight benches featured in the exhibit. The other benches use braids made with garden wire, headscarves, leather or copper wire by hairstylist Shamara Roper. Postcards and works on paper made by multidisciplinary artist Teresa Farrellare are also displayed inside the plastic quilts on Barrington mother’s bench. “Alvaro’s commitment to community is evident in him welcoming so many artists,” Olukemi says. “To be able to see the passion and heart that he put into this work is a privilege.”

In the south Duveen gallery, Barrington says he was keen to explore what it meant for his late grandmother, “a woman who was well into her later stages of life,” to take him and some of his cousins in. He tells me he distinctly remembers the “small shack in the countryside” he lived in where “when the rain would come, me and my cousins would run into the living room, and it would be hitting the roof.” He remembers how safe he felt living there. “The idea of feeling protected was a type of labour my grandma had mastered,” he says. That extended to her living room furniture, coated in protective plastic. “She wanted to tell my mum that ‘even though you are working in America, every time you come back, it will be like you never left.’”

In 1990, when Barrington was eight, he moved to the US, and lived in Brooklyn with his mother until she passed away in 1993. “After she died, my entire community came together to raise me,” he says. “All they talked about was how much my mum had done for them.” Hearing that her neighbours were being denied bank loans, she started a ‘susu’ — an informal savings scheme — to help them out with big ticket purchases. “She would hold the money down and then give it back out,” he says with pride.

When we speak, the real life Samantha explains how she’s been touched to see her own experiences reflected in the gallery. “I think about how the negative things of the world just disappear at Carnival,” she says. “You get to be free. You get to be with your people.” Of his own wishes for the exhibition, Barrington has one thought he’s held close for the duration of its run. “I’m hoping mama and my grandma feel like I’ve shown up for them.”

Credits

Text: Precious Alseina

Photography: Jebi Labembika