Today, Manhattan’s West Side Pier is the kind of place families and tourists go to sunbathe, relax in the park, and eat Wafels & Dinges. A waterfront replete with Citi Bike stations, with a $250 million artificial island-cum-music venue being built not too far from it. In short: a cash cow. Travel back to the 70s, however, and the pier was Grindr personified.

In the 21st century, queer sex has become privatised and individualised. Our conquests largely occur on our phones now: late at night, alone in our bedrooms. But back then, places like the West Side Pier were safe havens for gay men who wanted to meet, hook up, and then go their separate ways. From our perspective in the present day, the idea that scores of gay men had public sex in the middle of Manhattan sounds like a fever dream.

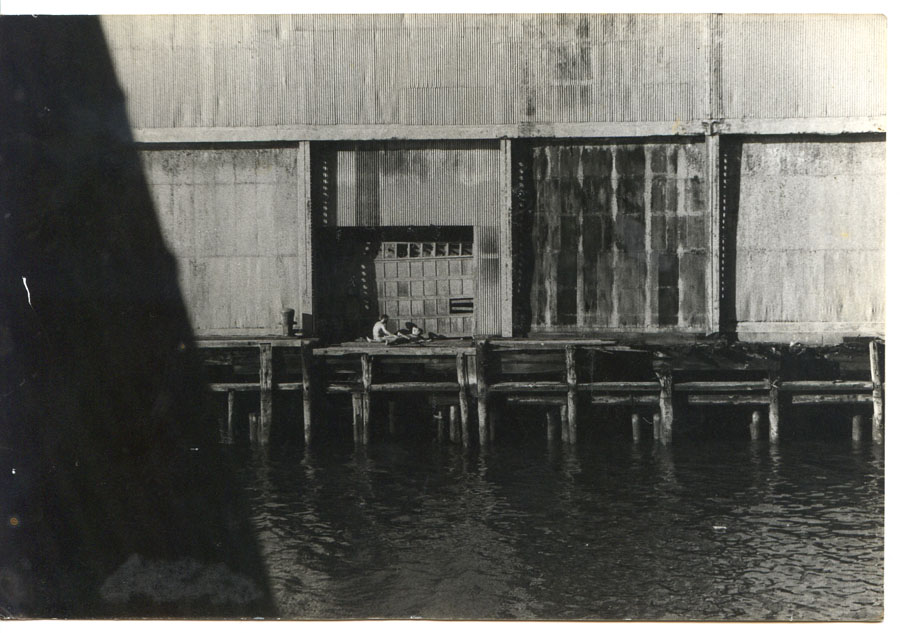

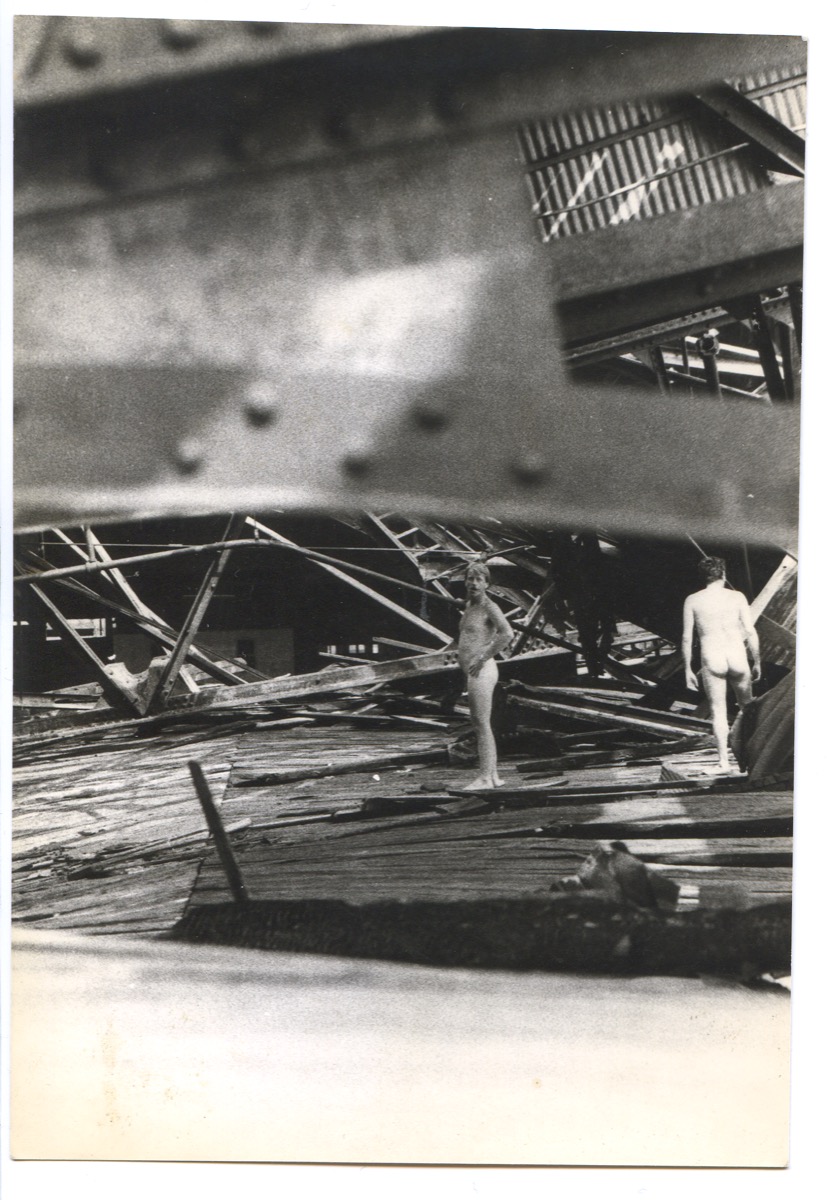

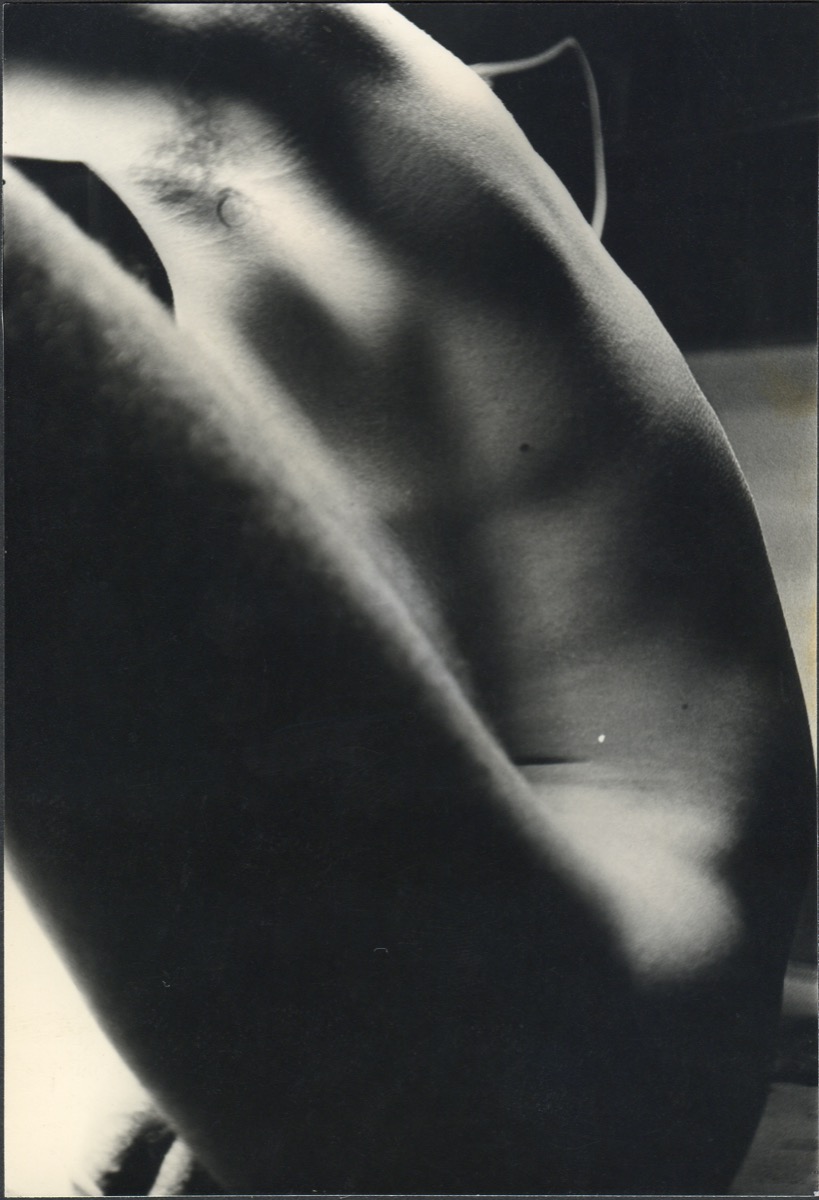

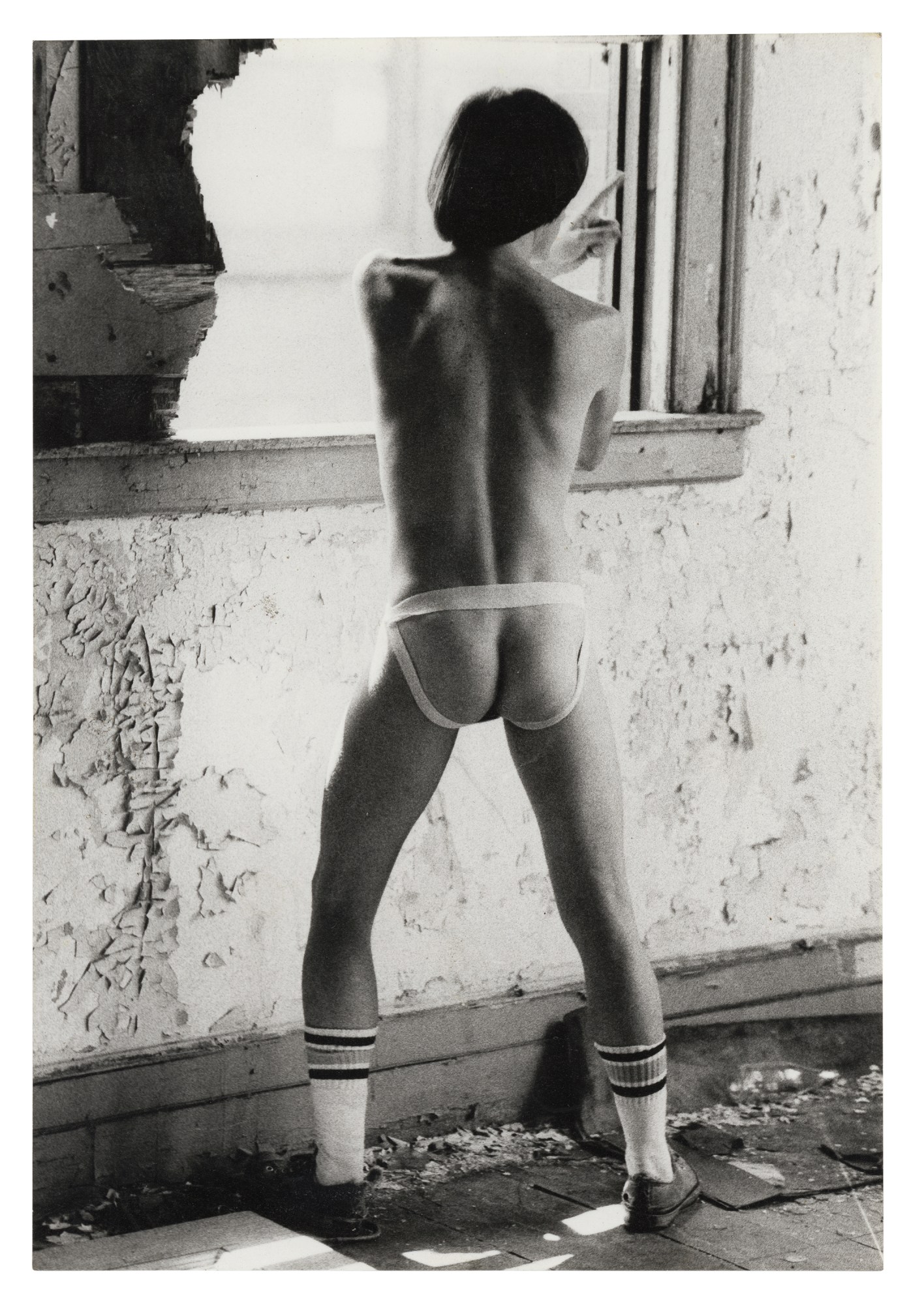

The piers were an enchanted place during their heyday — and late photographer Alvin Baltrop made the ephemeral hookups that occurred there a central focus of his work and his life. Over the course of three decades, he shot grainy, voyeuristic black-and-white images of gay men captured in the throes of hedonism: sunbathing in the nude, wiping off after a hookup, making out passionately. Baltrop’s photographic eye does not feel judgemental or, potentially worse, searching for shock value. These images feel like lush historical archives. Documentations of the very kind of love affairs Baltrop took part in himself. The Bronx-native held a special spot in his heart for the piers and the cruising that went on there. As he once said in an interview, “You did not care about the broken-down, the danger, the dirty, the smell, the raunchiness. You cared about meeting someone and having sex. Most of it was… bust a nut and keep going.”

Looking back on the forgotten history of the West Side Pier in the middle of Pride Month holds immense weight. It’s a reminder that, when it comes to locality — places where we can meet and be — the queer community has always been forced to hop from place to place, at risk of being erased by commercial and political interests. Here, Bronx Museum curator Sergio Bessa talks to i-D about the legacy of Baltrop’s career, the cruising culture of the 70s, and just how difficult archiving queer art is.

First off, why do you think Alvin is not as popular as other noted queer New York photographers, like Mapplethorpe and Warhol?

Bessa: When you compare Alvin to those men, it’s not that he wasn’t professional — he studied at SVA, he knew the craft very well, he developed his own photographs… But someone like Mapplethorpe was very ambitious and really wanted to strike it big. Mapplethorpe wanted to be known as a classic photographer, in the same class as Irving Penn. Baltrop, on the other hand, followed his passion. His photos were more than a stunt. Photographing the piers, for him, was a mix of research and archival work. He would park his van on the street and spend hours out there. I’m not sure he even thought about showing his work in galleries. He was just fascinated by his discovery of the piers.

When did you first encounter Alvin Baltrop’s work?

I’ve always been interested in learning about what the Bronx has contributed [to the art world since I’ve been working at the Bronx Museum]. I came across an issue of ArtForum in 2008 and Alvin Baltrop’s name was the cover. I read the article on him inside and learned that he was from the Bronx and the more I looked into his life and history, the more I thought he was a fascinating man.

And how did the exhibition on his life and work come about?

We knew a person who worked with the Alvin Baltrop estate. She was saying the estate was having difficulties with his archives because they didn’t have enough resources. I thought it would be great to get his archives here [at the Bronx Museum]. So in 2014, they came to us. We have a lot of Baltrop’s personal belongings — all of his photographic cameras, medical records, rolls of film…

What brought Alvin to the piers? Both in a personal sense and in an artistic sense.

In the late 60s, Alvin was in the Navy during the Vietnam War. He never got to Vietnam. He was mostly stationed around in the Atlantic. In ‘72, he came to New York and was living with his mother and brother in the Bronx. What I heard is that his mother discovered a lot of his photographs and she had a very strong, negative reaction. In short, he moved out after that. I think around that time he discovered the piers. Alvin was a proud bisexual man — he had girlfriends and boyfriends. He was just this very sexual person. What I learned from another essay, is that previous to the piers he cruised parks in the Bronx and Central Park. He explored a lot of queer cruising spots in the city. And at some point, he was a bouncer at a notorious gay bar on 2nd Avenue and 4th Street.

It feels as if Baltrop was enmeshed in his work. He was not simply photographing the piers; he was taking part in its culture.

Yes. There’s this side to his work that is very personal, very diaristic. The exhibition begins with the photographs he did in the Navy. During that period, you already see the formal elements he hones in with his photos at the piers. You see the homosexual gaze… Baltrop didn’t photograph because he thought, ‘Oh, this will sell!’ He photographed what was around him.

A photograph that really stands out to me is Baltrop’s portrait of Marsha P. Johnson. The image could easily fit inside a fashion magazine.

Well, at that time, no one thought that Marsha was going to become the icon she is today. I don’t think Marsha was engaged with the sex scene at the piers. She was just one of the people that Alvin met. I love that photograph because there’s so much dignity to it. It’s almost like Marsha is the First Lady.

Is there any background information you can provide about the portrait?

This is the difficulty with Baltrop’s work. He didn’t give titles to his photographs, and we don’t know the precise year most of them were taken. He just photographed compulsively. There’s a huge number of his images that haven’t even been developed. I feel like the Bronx Museum is simply opening the lid on how important his work is with this exhibition. Not only in terms of gay history and the gay community, but also in terms of photography in New York.

What are the specific difficulties of working on an LGBTQ+ exhibition like this? Because, so frequently, queer history and art are not as meticulously archived as they should be.

This history is still very young. I understand the challenges and the difficulties but, at the same time, there is still so much we can do in terms of collecting our history.

One of the things I’m very proud of is inviting Alvin’s friend — who is also a photographer — to write an essay for the catalogue. He has this first-hand witness and relationship with the subject, and he wrote the most beautiful homage to Balthrope.

Setting is so important to Baltrop’s work. He captured cruising spots that, today, have been covered over by condos, Sweetgreens, Citibike Stations, etc. What significance to LGBTQ history do these bygone queer meeting grounds hold?

I did not live in New York in the 70s. But I remember living in Brazil and the hippie counterculture taking over everywhere at the time. So for me, I remember trying to understand the cultural and sexual changes taking place. People all of a sudden felt like they could have sex in public! The change was happening on an international level, too. I read a biography by David Wojnarowicz because I wanted to read the life of someone from Baltrop’s generation, who was also living in New York at the same time. I found out David lived in Paris for a few months in the late 70s, and he would also go to the park late at night and have sex. So this was happening in England, Paris, Japan — everywhere. It was this global sexual revolution. And Baltrop’s work is the strongest representation of this cultural shift.

What is it like looking at Baltrop’s work through the prism of Stonewall’s 50 anniversary?

There are over 170 photographs we’re looking at, so for me, it’s almost like putting together a film scene by scene. Exhibitions like this are reminders of the struggle. We are living the lives that the people before us planned and fought for. I am a gay man, I am married, and think we have come a long way. We have a presidential candidate who is openly gay and married. We’ve come a long way.

Finally, what are some of your favourite photographs from Baltrop’s archive?

Marsha definitely. I also really love the photographs from Baltrop’s time in the Navy. He might have had a boyfriend in the Navy. There’s a really beautiful photograph of a young man looking at him and you can sense the desire. Just in the way he frames another man. There is also so much innocence. I think the image is really, really beautiful.

‘The Life and Times of Alvin Baltrop‘ runs at the Bronx Museum from August 7, 2019 to February 9, 2020.