Back in the 90s, photographer Roe Ethridge did a beauty shoot for Allure magazine: a “how-to” guide for make-up. Unaware of the subtleties of beauty photography, Ethridge over-lit the shoot to avoid shadowing. Later, his mentor, the fine art photographer Ron Jude, looked at polaroids from the shoot and noted that one shot, a portrait of editor Kathryn Neale, was “a great picture,” says Ethridge. Ethridge had suspected as much, and the roots of his conceptual art practice took hold. “I just loved as a conceptual practice doing both fine art and commercial work,” he says. “I thought, This is wrong. It was just sinfully delicious.”

Since then, Ethridge has brought commercial work and outtakes into his fine art practice, and also flourished in the fashion and advertising worlds. He’s worked with brands like Kenzo and Balenciaga, most magazines including yours truly, and even did an extended project with banking behemoth Goldman Sachs. Every project, commercial or personal, can contribute to his artistic output. Exhibiting with Gagosian and Andrew Kreps, Ethridge places commercial work alongside personal fine art work, deriving meaning in juxtaposing the disparate styles of photography. His exhibitions reveal the elasticity and “faux” nature of photographs; any one image can be used to sell or excite, confuse or disturb, depending on its context. For example, in his 2011 Gagosian show Le Luxe II BHGG, Ethridge used polished photographs of posing models. In a magazine, the images seduce. But placed alongside still lifes of ash trays in the exhibition, there’s a strong element of cynicism.

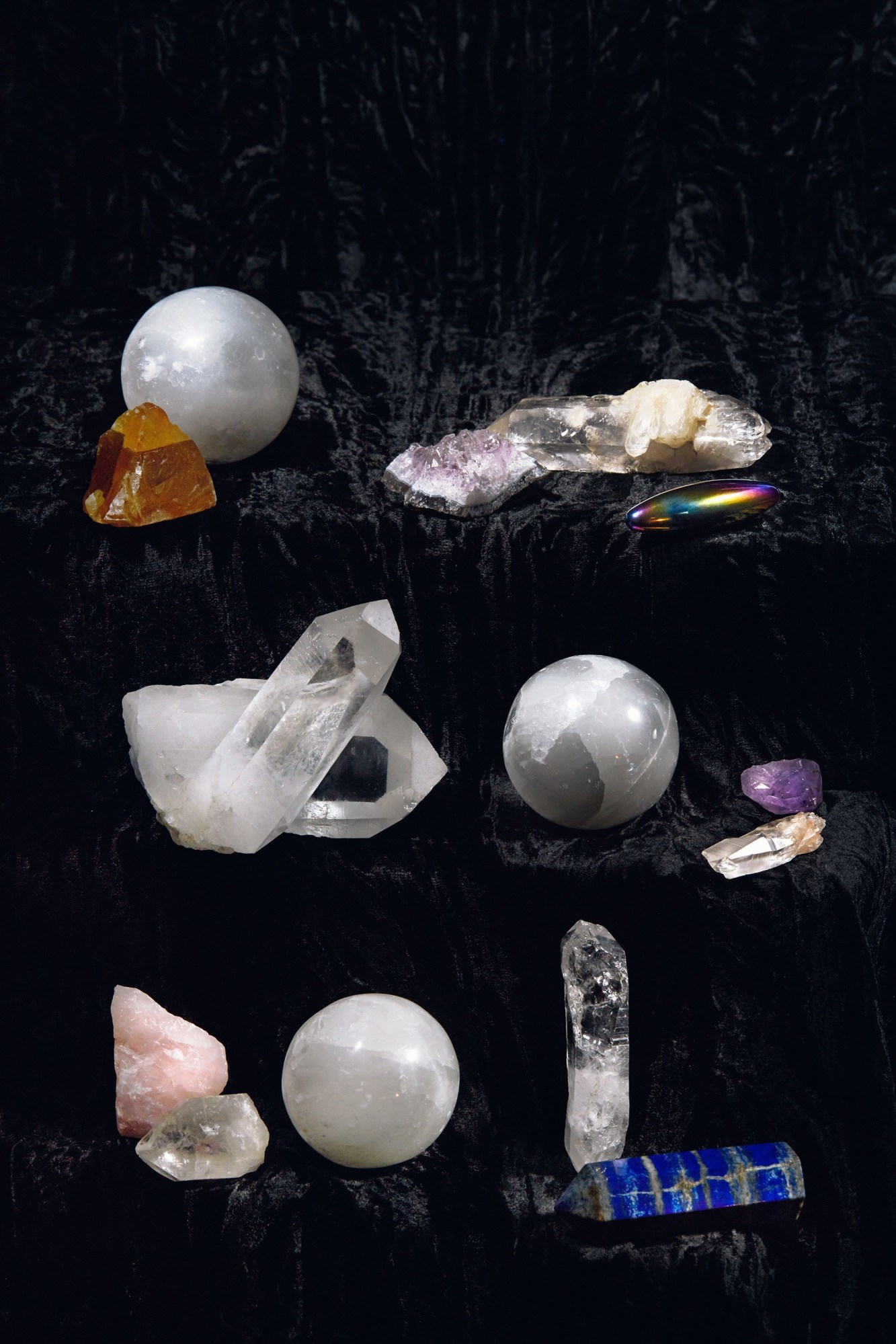

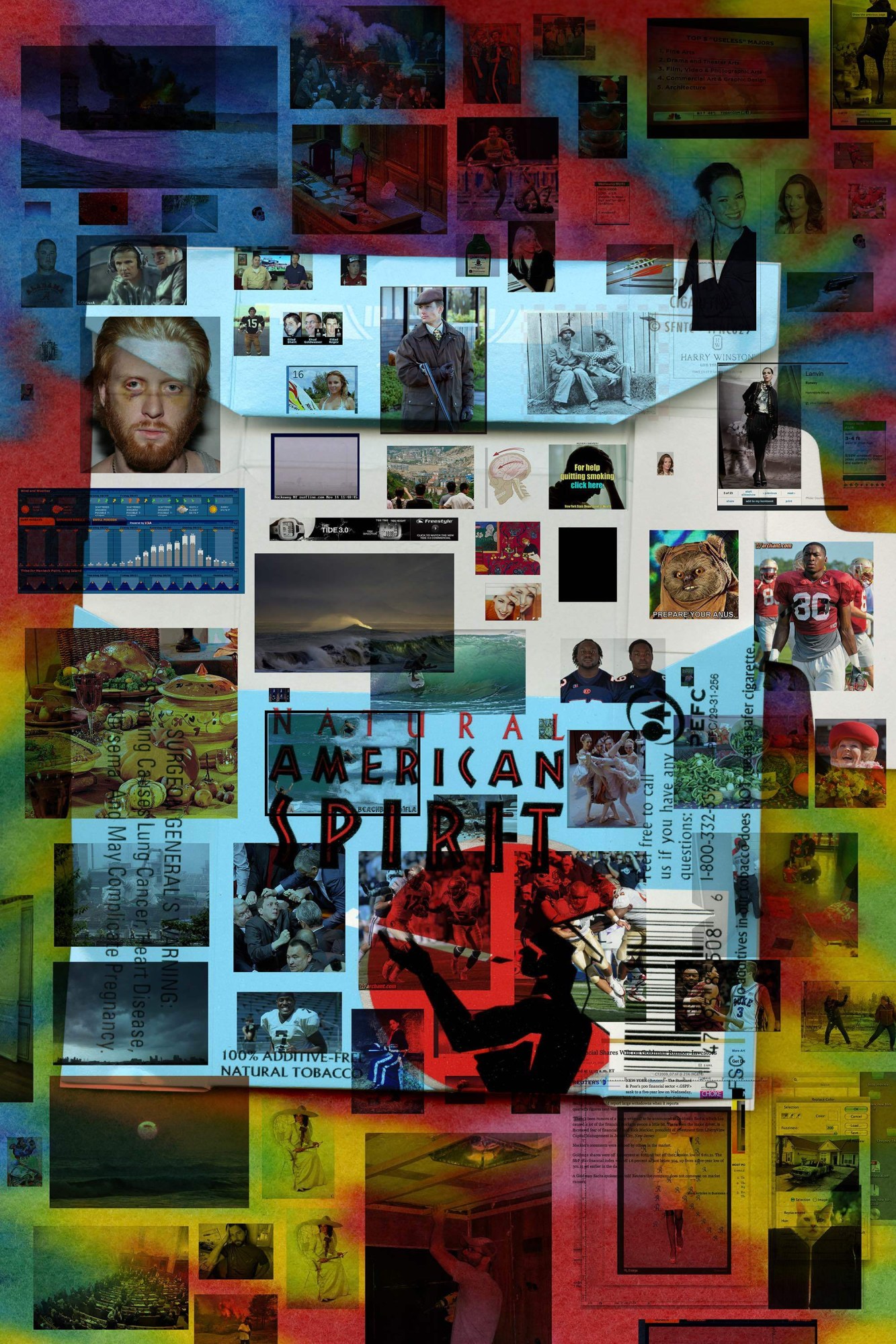

That tension is present in Ethridge’s latest solo show at Andrew Kreps Gallery, American Spirit. The title, pulled from a pack of cigarettes, purposefully resembles that of Alfred Stieglitz’s picture Spiritual America that shows a castrated horse (a title also appropriated later by Roe’s friend Richard Prince).With the volatility of the modern political atmosphere, Ethridge sought imagery that was distinctly American but also apolitical: The Rocky Mountains, The Rose Bowl Pac-12 college football championship, an American brand of cigarettes. Also in this exhibition is a new series called “Pic n’ Clips.” Named after folders on the artist’s computers, countless images were applied to blank Photoshop canvases randomly. Ethridge speaks to i-D about the exhibition, and its place in his idiosyncratic career.

You’ve created a practice where every shot you take can hold importance in your larger career output.

I wanted the power of invisibility to blend into whatever I was working on, whether it be architectural photography, or beauty, or fashion, or personal things that get brought in. I wanted this “everyman” quality to blend into this idea of the atomized image.

There are times when it’s obvious during the shoot that something is working, and sometimes it’s obvious that this is straight commercial photography. In a picture from this show, I was working for Vogue China, and the background spoke to me. I was just taking pictures of it in between takes of Lexi Boling. I asked the digital tech to see the shots, and by accident somehow he had layered the images with the logo for Vogue China. So it was the Chinese lettering on top of this background. It was too good. That’s an art work for me. It’s accidental, but it’s accidental in the way that Warhol and Rauschenberg would make a screen print and let the accident take over.

You’ve discussed the idea of a fugue as a mental state [in which a person suffers temporary amnesia] and a compositional structure in music [in which two or more voices build on a subject that is introduced at the beginning of a composition] as inspiring to you. How so?

It hit me that there was something necessary to have an “identity amnesia” where the work isn’t about me as an individual but as a generic photographer. Then, after learning what a musical fugue was, that changed everything for me in regards to how obsessed I was with the sequencing. With the InDesign program, it felt like I was composing music. There’s a synesthesia going on: you put the images in a sequence and it starts to make sound. That sequence, like the fugue, is a formal thing that is actually quite psychedelic. I like that.

How did the “Pic n’ Clips” come into fruition?

Any image over the last 12 years that I didn’t want to forget, I’d put it in these folders called “Pic n’ Clips.” But making individual prints of these images felt gratuitous. We had a reflector panel in the studio that was 72 X 48, while looking at it we thought, “That’s a nice size, it’s big.” What if the Pic n’ Clips were just on there? Not organized. So I grabbed 20 of them and just dropped them in there. It was to take the energy of the survey show but do something where I take all this work and leave nothing excluded, and have it done in a day.

Given that the title of the show is American Spirit, are you thinking about America differently with the political climate?

The name was there before Trump got elected, and a part of me thought, “Did I fuck myself with this title?”

You could have named it anything right now though and critics would called it, “Roe Ethridge’s Trump show.”

It’s true, the timing couldn’t have been worse. But then again, it’s perfect. The title started to guide things. I wanted to find images that are ambivalent about who the president is. The mountains don’t care who the president is. So I photographed The Rocky Mountains. Making politically reactive art isn’t my bag, but at the same time it’s very hard to deal with the world as a photographer and not. I can’t be totally insular.

American Spirit will be on view at Andrew Kreps Gallery from February 24 to April 8.

Credits

Text Adam Lehrer

Photography Roe Ethridge