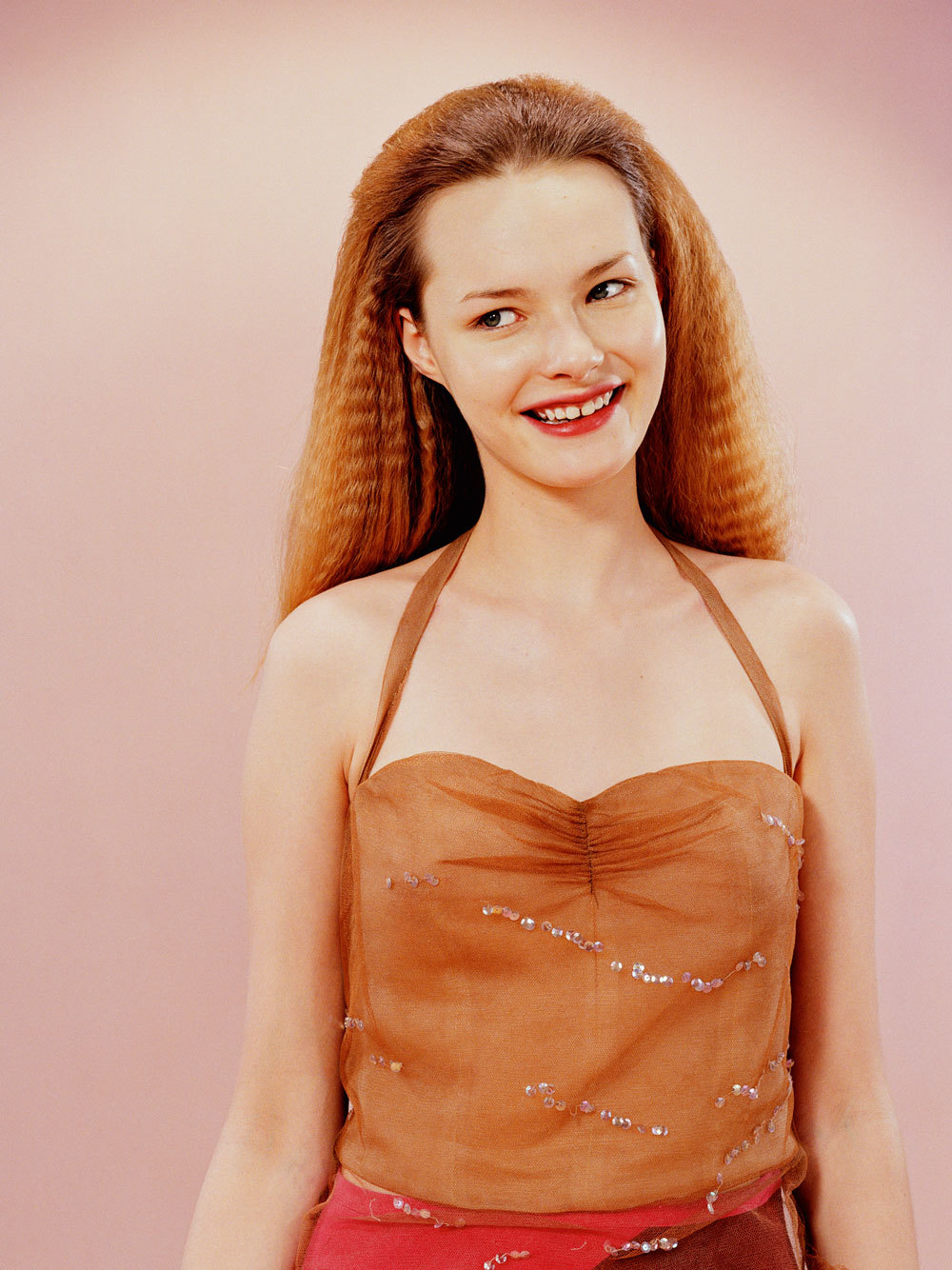

In 1986, when Martine Sitbon started her brand, the young Parisian designer invented a bold new silhouette. It managed to be dreamlike, punk tough and glamorous and sexy all at the same time. Parkas and jumpsuits, lace layered over thick cottons, oversized pieces rubbed against shrunken, skin-tight plays on proportion. She calmly, confidently and curiously mixed everything up.

With her crew of up-and-coming cool kids (Kate Moss, Nick Knight, David Sims, Craig McDean, Kirsten Owen all collaborated with the designer) and her husband, the art director Marc Ascoli (with whom she’s been sharing her life for 30 years now), Martine Sitbon helped invent and define the new approach to fashion in the 90s.

Better than that, she invented the idea that style is a very personal chemistry. She encouraged thousands of women to express themselves, in all their contradictions. In 2016, just two years after the end of her last project, Rue du Mail, her work is celebrated like never before, by a young generation that considers Martine Sitbon as their queen. Something that ensures fashion has beautiful days ahead. On the release of a beautiful new retrospective monograph of her work, we sat down with Martine to discuss An Alternative Vision.

Why make this book now?

This book is a history of my life, well, my professional life at least – so I wanted to take the time to immerse myself in it. There’s also so much to organise, so many archives to look through, then beyond that, editing, choosing… it covers almost 30 years of my career, so it really was a work of introspection, to understand what was important to put in and how it could come together. I needed a lot of time for that, I had that chance with Rizzoli. They were interested in a more personal approach. Nowadays, in fashion books, there’s an advertising side to it. But Rizzoli allowed me to evoke my work more in a personal way, to help me understand my most important sources of inspiration. These vary depending on what I’m working on, but in the end I always seem drawn to the same things. So, it was good timing, we went deep into things, worked as a small team. I didn’t just give everything to people to put together, I had an intern with my team at my house. I like things if they happen organically.

You like to work in an ‘organic’ way, with people close to you. Is it a way to have more flexibility or more control?

A little of both in fact. More flexibility, because I don’t like things being rigid and at the same time it allows for improvement, and to arrive at something more considered. When I worked on my collections there’s a lot that you don’t see in the final output, so I wanted a chance to go deeper into my creative process, have freedom to do that. I wanted to show the moodboards, the mock-ups, the studio work; it’s an anthology, it’s important it resembles me.

The book is titled An Alternative Vision, why?

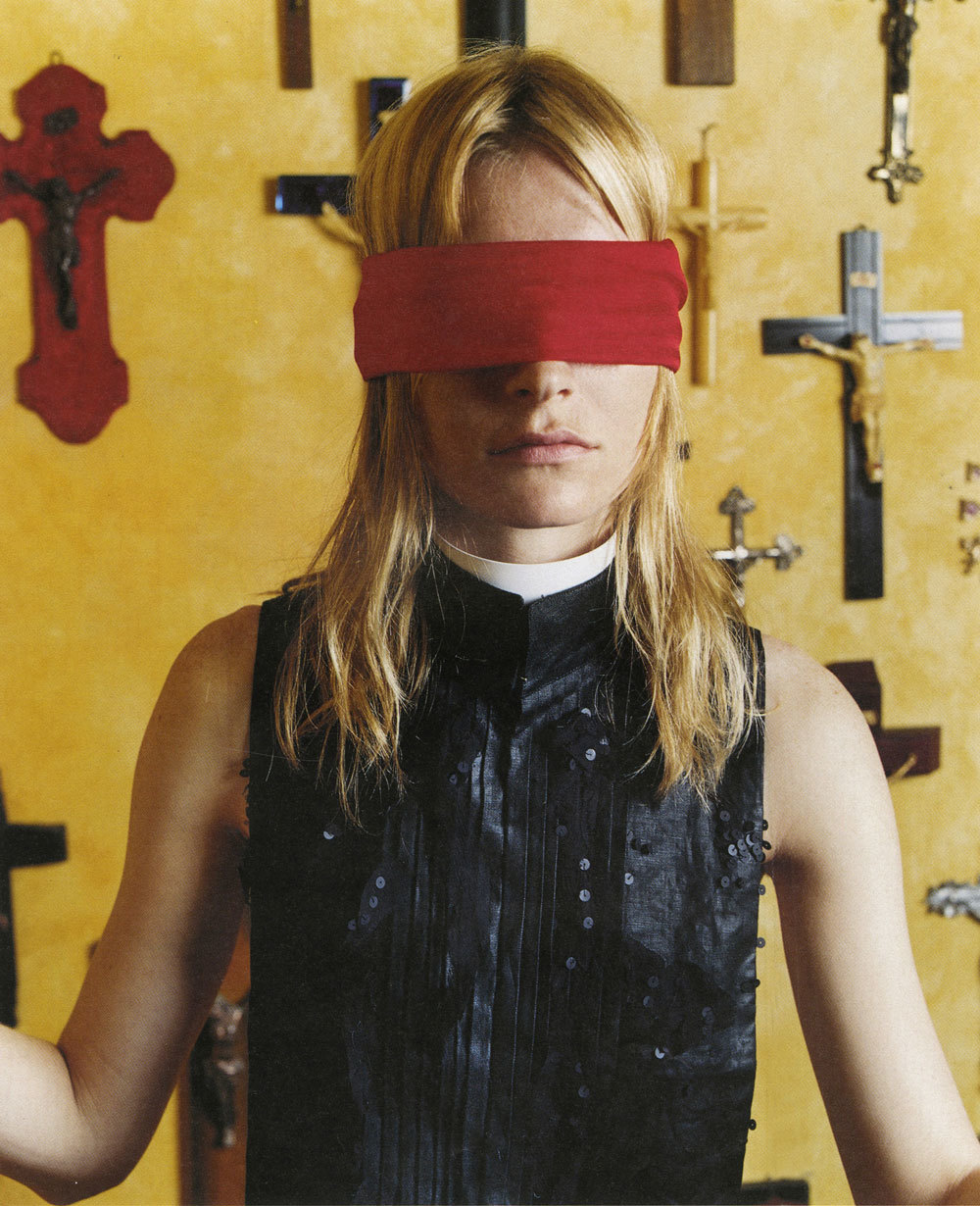

I thought of alternative rock. When I go to record shops, it’s generally the section that interests me. But it’s not only that, I wanted a title. I didn’t want Martine Sitbon, and also didn’t just want to call it Nineties Fashion. I wanted something more profound. It’s true that I’ve always worked in fashion, but I tried to never fall into the classic way of thinking. I always try to question system, even if I’m part of it. So, it’s alternative.

Alternative, in this sense, is a term very connected to the 90s.

Yes, I wanted there to be that 90s connotation. For a very long time it seemed people summed me as simply 90s fashion. But it’s not quite like that, I started in 1986, and I was still working two years ago.

You say you’ve always put the fashion system into question; is that one of the reasons you make fashion?

Yes it is for me. But it was different in the past. I needed to work for it. That is why I say my work was precursory. Things had to be created while others had to be changed. Fashion needed a new system. Journalists often tell me “Martine, you are a visionary.” I needed to chart a new path, like Helmut Lang or Martin Margiela did through their own work. Each one of us have drawn new routes in our own manners. For sure, mine was less strict and repetitive than Martin’s one – repetitive being a good thing here. He used to cover the faces of his models. For me, it was the opposite, I have always loved girls, models, how they interpret fashion. Today, models are a bit less inspiring or interesting, except Kate Moss, but it’s another story with her. The time I am talking about was just after the big wave of supermodels, I loved the different girls embodying fashion at that time, they had real characters, they were inspiring, they were telling stories with the clothes they wore. There’s a kind of opposite mood now, where some designers say girls on the catwalk are not important and that clothes should prevail.

That might be because you are a woman?

Because I’m a woman and I can see what fits a girl. A piece of clothing has to take life, feel like it’s made of flesh and bone. You can show and see it as a piece of art, but it is not the way I like to do it. I like it be part of life. It is something I think I helped change in fashion; like putting a model in a show in just a skirt and t-shirt. It was just unthinkable for a designer to do that when I started. For me a skirt is a skirt, it’s the girl who is wearing it who is important, she bring the attitude. For me the girls are not simply models, they are leaders.

Were you aware at the time that you were doing something revolutionary or was it something completely instinctive?

It all happened spontaneously. The girls were not street cast or anything like that, the girls we cast were the ones I found interesting, who had a lot of personality. Girls I’d want to know and hang out with. Nothing happened randomly. The trench for example, it seems stupid now because there is the Burberry trench but when I designed a trench for a collection, I couldn’t sell any, people were not looking for that in high fashion. It was important for me to do it anyway, like the skirts. They gave attitude. It was not easy. And doing it, I knew I was taking a risk. It wasn’t something random. I did it and owned up to it.

Nowadays, everybody dresses like that. It has become normal, banal even. In one of the texts in the book, Fabrice Paineau says that stylists’ work has become to reproduce this exact silhouette…

Fabrice worked for me a long time ago, that is why he knows me that well. He used to say that I worked like a stylist. Maybe because when I was younger I never thought about designing clothes, but I always enjoyed creating looks. I used to go to flea markets, I’d love to mix girly dressed with military jackets, etc. And then music turned me onto a lot of things to.

I feel like it is something that a lot of female designers have in common, don’t you think?

Yes, as a woman it’s normal. We project ourselves. Which doesn’t mean that I want to wear all the clothes I design and thank God I never had to! I am kidding, of course. I always try and imagine a girl that I like, coming in a room, a flat, wherever I am, wearing something nice. I imagine a silhouette, a pleasant one. I don’t want her to turn into a woman I don’t like. Her silhouette is a structured and precise fantasy. I want to be her friend. That’s my spirit.

There are not so many female designers doing womenswear at the moment. Do you think there needs to be more women involved in it?

Yes totally, but I didn’t think about it this way. I wanted to do shows and didn’t question it. My way was quite extreme and people used to say my work was pretty “English”, pretty DIY. It was not always easily wearable. My fantasy was poetic. Not very real, even if I wanted to bring reality in my work. The moment I opened my shop was a turning point for me. It was not about strategy. It was important to the development of my universe and for girls to relate to it. From that moment, parts of my work were bound to disappear. When girls walked in the shop to try on clothes and those clothes wouldn’t fit them, it upset me. It brought me back to reality. I wanted women to feel good in my clothes.

Was it about female solidarity?

Yes. Mademoiselle Chanel once said something like : “don’t design ugly things because people might actually wear them.” I find that very accurate.

There are two types of designers, those who dress people up and those who disguise them.

I can understand conceptual designs of course, contemporary ones; I understand the desire they convey. That being said, there are so many clothes everywhere that it has become a way to communicate. I don’t have anything critical to venture about that. I understand why designers develop a concept, an argument into something commercial. It is the era we live in.

You developed a very subtle style, a complex vision of femininity over your career…

I’ve always been very attached to the notion of balance. It would be way harder today for a designer to think like that. Now, you have to make sure people understand your vision in a few images, in a split second.

Do you think fashion is not as complex as it used to be?

No. There are still collections like that, which is great otherwise we would all be asleep. Fortunately, fashion still moves us, challenges us, it would be so boring otherwise! Shows would be useless and brands would only have to sell their clothes, that’s it. If you bring people together to come and see a show you need to create a form of communication. Mine were different: I wanted to break something to invest the mundane. Now it’s the banal that needs to be cracked down. In the end, it is the same intention, the same speech in a different era.

You choose to highlight ten of your collections for the book. Wasn’t it very hard to choose just ten?

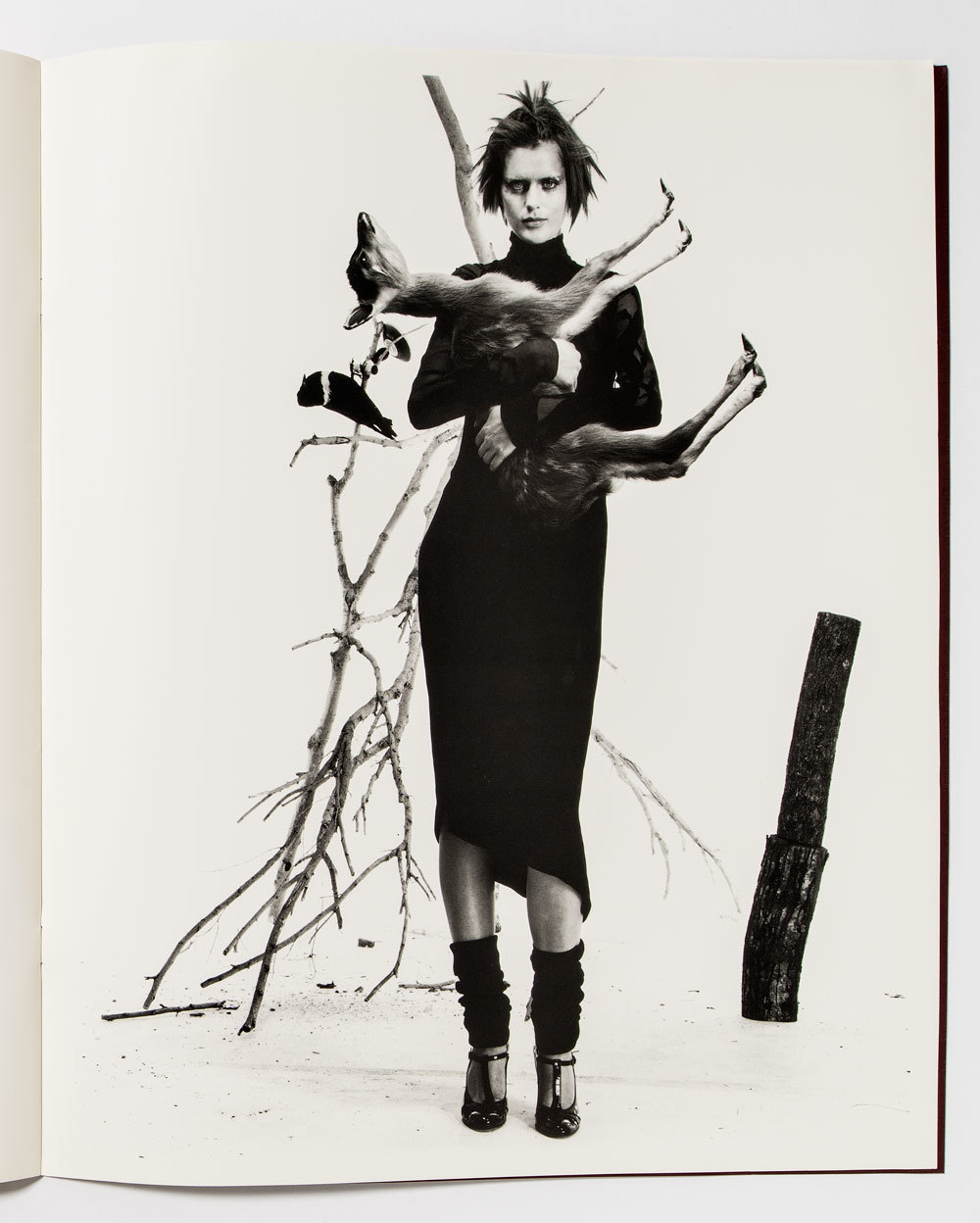

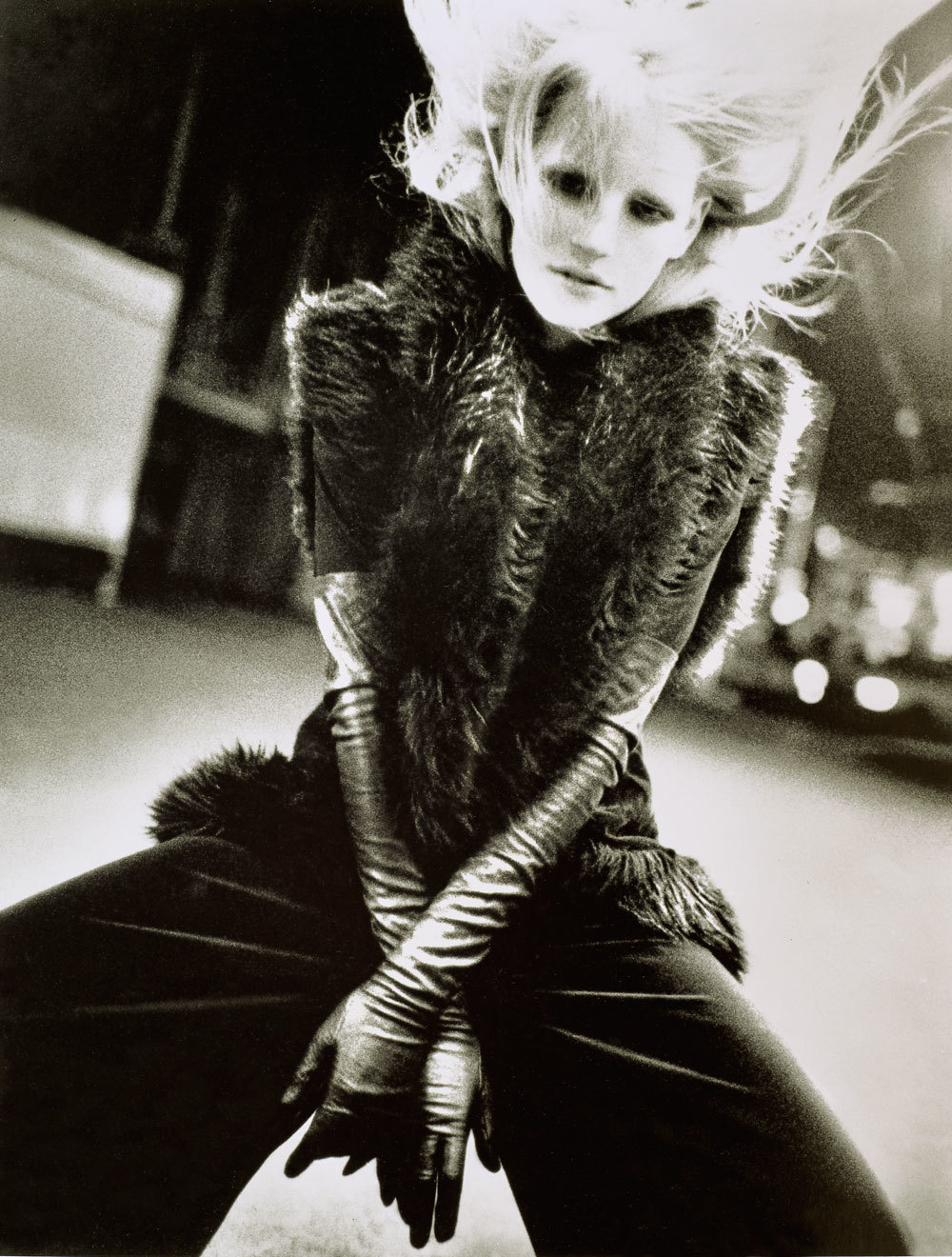

Of course it was. There was so much material, just even in terms of photography. But it was interesting to see which pictures were touching me the most. Those that were the most important. I probably didn’t even put them all in. There are a lot more that I love but I tried to highlight what I really enjoyed working on. I liked working on the rock side of the collections, the childish spirit, the graphics… I’d get inspired by contemporary dance, working on the movements of the clothes, the fabrics, developing a gothic side to all of it. I tried to review all that in the book, catch the essence of it.

How would you define the essence of your work, after 30 years of your career?

It’s difficult, there are so many things. But there is something very clear that was there since the beginning, from the first collection until the last one – a clash between something very soft and something much harder, something deeply masculine and something very feminine. I create right between those two poles. I like androgynous girls while also admiring femininity, a poetic form of softness, something almost childish.

Your vision of women seems to have always settle between two worlds. Two extremes. How did it evolve?

I don’t really know. I never knew where it was coming from. But it was the result of all I had assimilated since the age of 12 or 13. I was very curious, passionate about music and fashion in the 70s. Music plays a huge role in my life, it was my own culture, something that didn’t come from my family. Then I started travelling back and forth to England as my parents were sending me there. I made it my own experience, not necessarily the one they had imagined for me! They couldn’t control anything I was doing so I was going to clubs a lot, I was about 14 or 15. It became my culture.

It feels like you had an English underground fantasy mixed with a more classical Parisian education. You could have renounced one or the other.

When I leaned towards the English side, I denied my Parisian side, to be honest. After a while, things got more balanced. I love Paris. I wanted to live in London or New York for awhile, I was attracted by the rich musical and artistic culture of these cities, and the fashion also. I loved the Velvet Underground, which inspired the Warholian spirit of my first collection, which had a real Edie Sedgwick edge to it, the dress with three holes in it – that wasn’t necessarily very popular when I designed it, it only became so about 15 years later really. But I was really sure about what I was coming out with. It got finer and finer, gradually, of course. I think when you are a teenager you necessarily tend to fantasise about everything and see things better than they are. It something I haven’t experienced as an adult, which is why I still see it as something amazing. It was a pretty dark period of time, a destructive one. But as I was young, it fed me. I also studied in a fashion school, Le Studio Berçot. I loved Marie Rucki, the director of the school. It was my elder sister who really pushed me to do fashion.

How did your sister felt that you had to do fashion?

She felt that I needed to find something. She was scared things would spin out of control. It happened right at the perfect time, I didn’t ask myself twice, I was in my place. Fashion became a self-evident fact. Everything fell into place, and the Parisian tone to my clothes came soon after. My mother is a very elegant person. As a teenager, I really didn’t want to look like her but I could feel something touching me in her attitude. When I started at Chloé, things felt easy as I had this heritage. I love couture, the way a piece of clothes is elaborate.

With Chloé, you were one of the first to revive a house. Then you launched your own brand, then Rue du Mail… Where were you most at ease?

In my own fashion house, with my name. I worked at Cholé alongside doing my own collections. I loved working there, I stayed for about five years. I learned a lot about craftsmanship, about couture even. I am very curious so I got very interested in everything that was going on. But at the same time, the Chloé woman wasn’t “my” woman. Maybe it helped me to define the Chloé woman more precisely? I didn’t want the two collections to look similar. For my own brand, that pushed me closer to a cool reality, to the kind of girl I love.

So is it easy to create under your own name?

Yes, but it took me a while. If I look back, my favourite time was when I had my boutique, Rue Grenelle in Paris. I was in direct contact with people wearing my clothes. I loved the atmosphere of the place, we organised exhibitions there… It was a comfortable boutique with big sofas. A cosy place, I liked it a lot. Creating under your own name is difficult, mostly at the beginning. Then you get used to it. You need to figure out how to place yourself at the beginning and it is not an easy thing to do. After a while, I grew more at ease, with this boutique also. And it wasn’t a brand, I was just a designer. It wasn’t a huge house with 500 shops all around the world. I was close to it, it was something organic, allowing flexibility and control. Things weren’t too difficult for me. You just need to do things in harmony with yourself. Stay true to yourself. Then, things adapt, and the system does also.

The world fantasises about the 90s today, it’s a very fashionable decade. As someone embodying this time, how do you feel about it?

I like it. The 90s was not only about clothes, it was about an attitude. That’s something that fashion has been missing these last few years. It felt like a very creative time, very individual, things weren’t uniform. The grunge thing felt lively and real, less glamour, less showy and opulent. It was a real aesthetic.

How do you feel about young French designers today?

If you look at it, Paris is not so far from what it used to be in the 90s, grunge has come back and things haven’t really moved on from that point. I never saw the “American style” take over Paris and Parisian girls. Some French fashion houses did develop such a style but it was more about expanding a commercial vision of women and fashion. They didn’t sell those clothes, it was about selling something else, it was about a mass market; a mass market wrapped in luxury though. So yes, I do feel way closer to current designers. I can relate to them way more easily. But I like Miuccia Prada a lot, she never stops searching. I am not very classical, I like inventiveness.

Do you miss creating?

No, I only stopped two years ago, and my life doesn’t stop there. I’ve made the most of my time, I travelled a lot. I’ve always loved travelling and I ended up travelling only for work. The book has taken a lot of my time also. I helped Marc… So in the end, I never sat down at home thinking “this is it, it’s over.” For the moment, the book is the priority, then we will see.

Credits

Text Tess Lochanski

Photography courtesy of Rizzoli