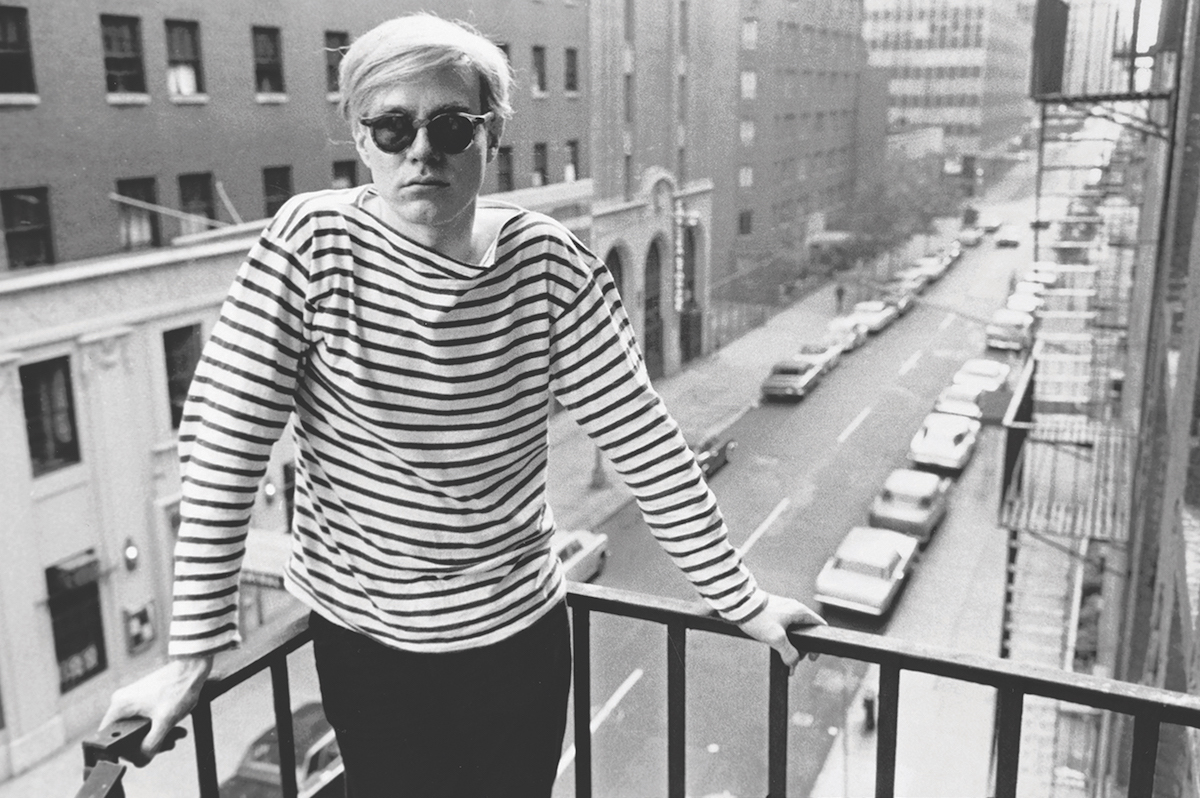

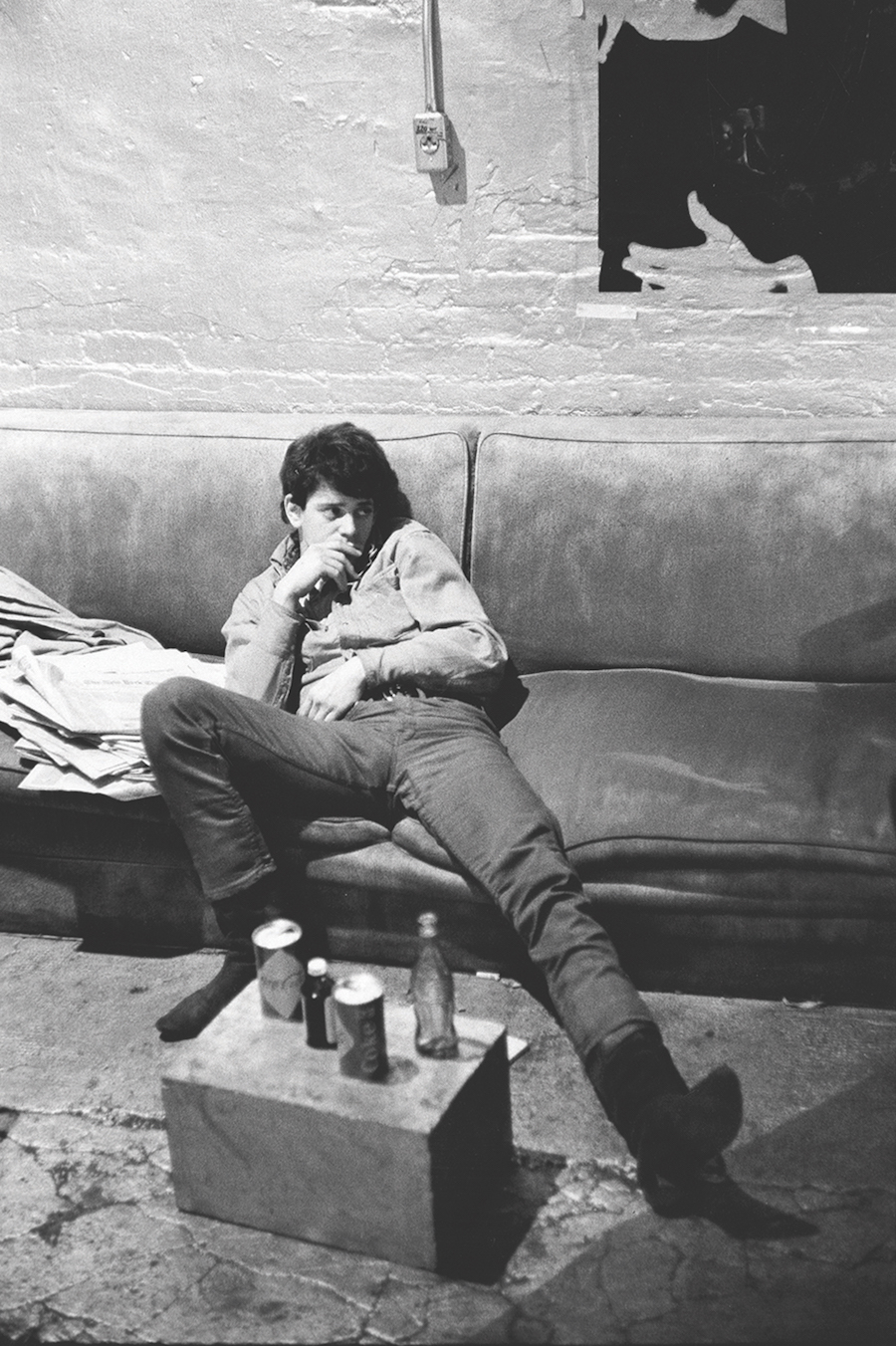

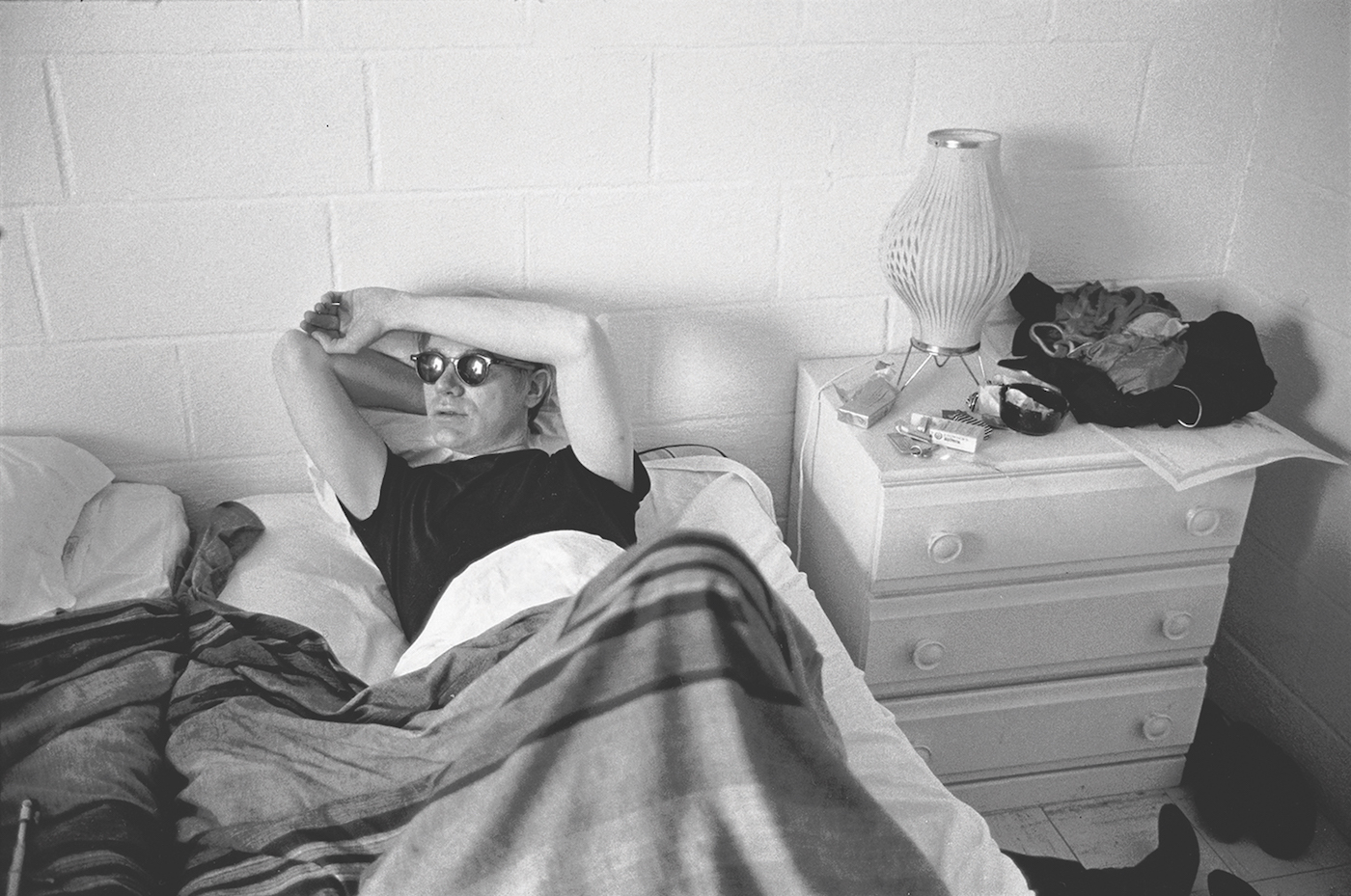

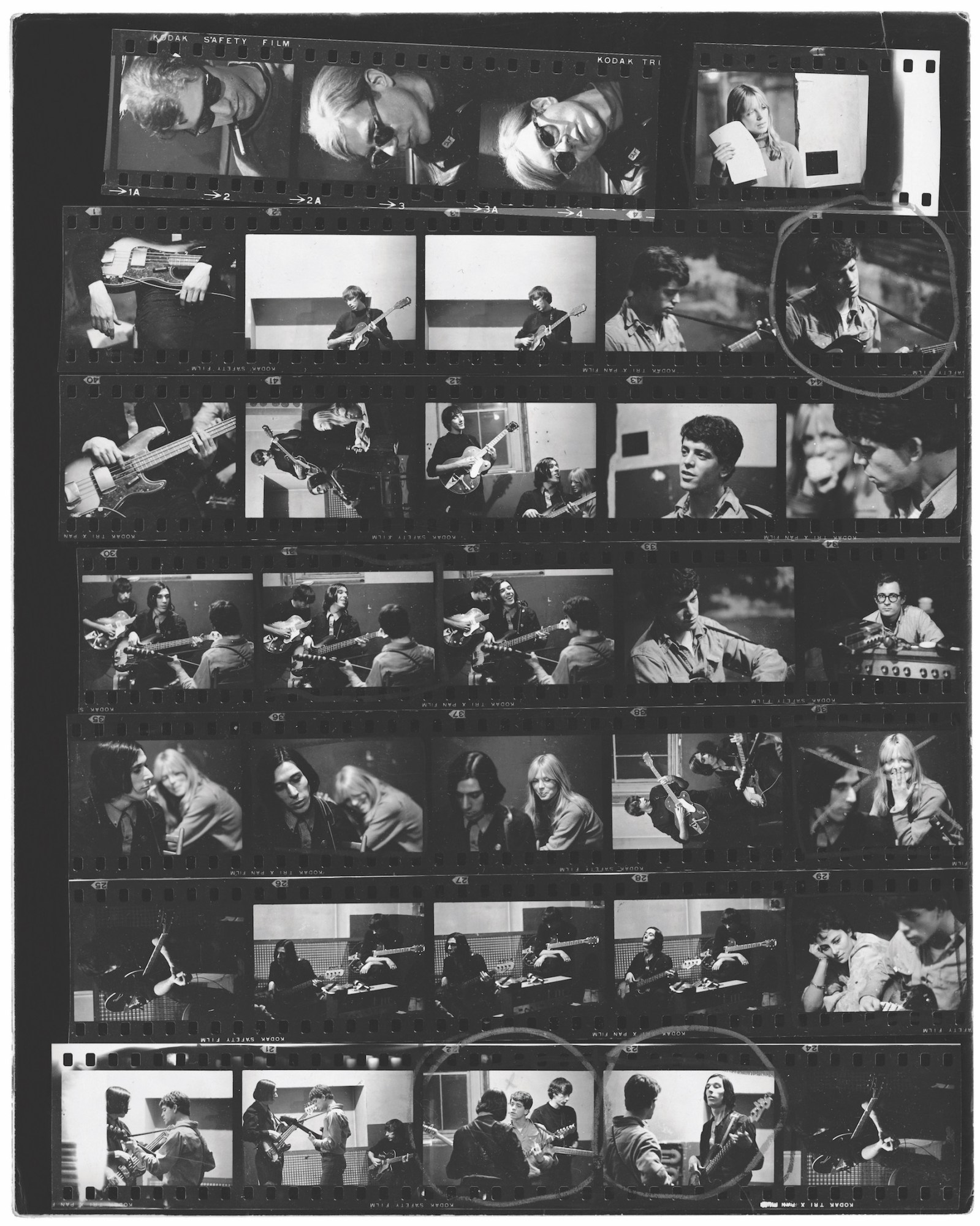

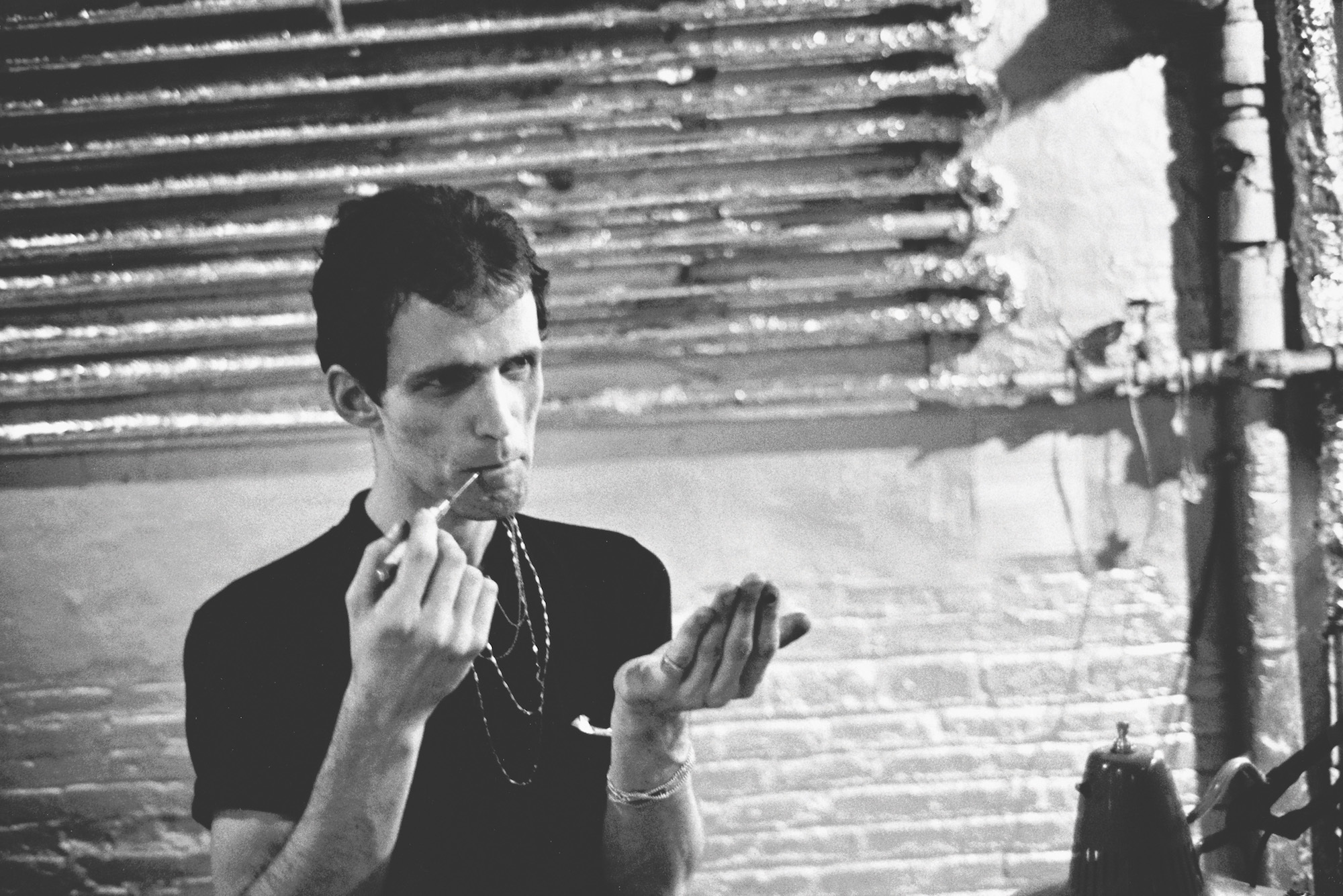

Stephen Shore was six-years-old when he got his first darkroom kit. By age ten he was starting to get serious about photography, receiving a Walker Evans book that left a lasting impact. At 14, Stephen sold three prints to the curator of photography at the MoMA. That he was kicking around Warhol’s Factory, daily, at 17, shooting the artist and his milieu, is almost unsurprising in the context of his precociousness. Andy Warhol was an exciting innovator, dedicated to exploration and creation, and Stephen was just as driven in his art — poised to discover, as he puts it, new ways of photographic seeing. And throughout his career he has done just that, continually evolving the medium in profound new ways. His images in Factory: Andy Warhol, capture iconic artists at work, but they are also an insight into the developing eye of one of the world’s greatest photographers.

In the introduction to your book of Factory photos, your work is described as “emphasizing the commonplace, elevating the ordinary.” Was that an aim for you, or was that just what came out of what you were interested in shooting?

I’m interested in culture, in what the world is like, and the world is not just about the dramatic moments, but the in-between moments. I remember a long time ago, in the late 60s, spending a few months in London; at the time there was a lot of turmoil in the US with the Kent State riots — six students were killed by the National Guard at Kent State — and a lot of other stuff was happening in the States that I was reading about every day in the Herald Tribune. It seemed like the country was falling apart. But then I got back and saw that life was going on; some really bad things happened, but life went on. The paper wasn’t saying that people were making their breakfast every day and stores opened as usual, it was reporting the news. But if you only read the news, you don’t get the texture of life. It’s often the ordinary moments that tell you what life is like. At the same time I was doing American Surfaces, I was interested in what looking looked like, and would pay attention to what I was looking at and what the experience of looking was at various ordinary times of the day — when I was riding in an elevator, or walking down the street, or in a store. This is what I was paying attention to. And I think Andy Warhol’s interest, his fascination with contemporary culture, his amazement at it, influenced me. When I was doing Uncommon Places I realized that this camera was the technical means of communicating what the world looks like if you see it in a state of heightened awareness, and I think that experience made me a better communicator. Really paying attention during your daily life means paying attention during the ordinary moments. That said, I’m not interested in photographing things I’m not interested in. I’m not picking random moments, I’m not trying to do things that are boring and uninteresting, I’m finding moments in ordinary life that I find interesting.

You’re quite prolific on Instagram. What is it that you enjoy about the platform, and are the shots you share taken on your phone?

Yes they are. Except for old pictures that I always identify as such, everything is done on my phone and within a couple of days of posting. I’m not interested in using it as a gallery of my work, going through old work and presenting it; I’m interested in taking pictures that I intend for Instagram. And that’s really what I’ve been doing for the past couple of years.

So you see it as an entirely valid artistic medium?

Absolutely. This is really what I’ve been concentrating on in my work for the past two years. I’m doing very little other work, it’s mostly Instagram and I love it. I like the community aspect of it. I like having this global dialogue with other photographers.

It’s quite unusual in that you actually engage with your followers. It’s not something you see often from a well-known artist.

More so than the commenting, it’s the visual conversation. I don’t follow a lot of people. I keep the number that I personally follow relatively low, because I want to be able to look at everyone every day; and on the other hand, I don’t want to spend all my day looking at Instagram. So I know that I can be sometimes brutal about dropping people. But if someone posts 20 pictures a day it clogs my feed and I’ll drop them because I really want to have this dialogue and look at everything everyone I follow posts. And there is a group of photographers who were all following each other all over the world. There’s some in the United States, there’s a group in England, a large group in Italy, one from Russia, and I think we all post almost every day. I really enjoy looking at what they’re putting out.

In your interview with David Campany you talked about how you always set yourself various parameters and different pictorial challenges. Is that something you do with Instagram as well?

That’s what Instagram is for me. When I started Instagram it was before it allowed oblong pictures. There were apps that let you post oblong pictures, but Instagram was basically made for squares. And even today when you do a vertical picture on it, on my phone I can see the whole image, but on my iPad I can’t, it crops it out a little. So in a certain way Instagram is made for square pictures, and I have taken pictures with a square format probably since 1970, and so I accepted these are the terms — just as a poet can write in sonnet form and in haiku form, I’ve accepted photographing in Instagram form. The other discipline is to post one picture a day. And obviously some days are better than others! I’m not ‘on’ every day.

Do you think you’ll do something with those pictures on Instagram?

I think I will. It wasn’t my intention when I started — I didn’t really have an intention — I enjoyed Instagram and I was going to just see what happened, but now I’ve got so many images that I like that; do you know the British publisher Morel? They did a small book, just as an edition of 200, a year ago, with my whole Instagram feed up to that point. And I’ve been involved in an American publication called Documentum; we’re doing four issues that are all about Instagram. It’s done on newsprint, so it’s not precious; it has the ephemeral feeling that Instagram can have. It’s not just my work, I’m one of the editors of it, and we’ve been publishing other people’s work. But I can see a book or books coming out of Instagram, and I can see selling prints from it or exhibiting prints. Right now when I exhibit it — my Instagram feed has been in a retrospective show that was on earlier this year in Berlin and Amsterdam, and what we do is just have a projector with an iPad on a pedestal that’s set to just show my feed and people can explore it, and whatever they’re doing on the iPad is projected onto the wall. So the whole feed is available. But I’m not ruling out other uses of it.

You said that when photographing for American Surfaces you wanted to take pictures that looked like seeing. Is that still a driving force for you or is it so natural to what you do now that it’s unconscious?

I would say it’s natural to what I do now. I spent most of 70s working out in a couple of different ways how to structurally control photographs, and now I don’t think about it. Now my mind is on other things and that’s been internalized.

You’ve also said that ambition is what separates those with talent who drift away from their art, and those who are driven to create. What was your ambition with photography? To take the best photographs possible, to change the medium, as you have said the best photographers have done?

For me it wasn’t so much a specific ambition, it was more just ambition. It’s not even that I wanted to do good work; I just had this drive to produce. I want to also clarify my feelings about students that I see; I see some people that have ambition that don’t have talent, and they in fact achieve a good bit. And then I see students that have talent but no ambition and I know that they’re not going to do anything. But if they have talent, ambition, and some degree of work ethic, that’s a golden combination.

One of the things you’ve said about Warhol was that he was constantly doing things, constantly making. Was that something you learned from him during your time there? Or was that just innate in you?

I think it’s innate. I don’t know where it comes from. It may not be innate, it may come from early influences, but I haven’t seen how to instill it in someone. I can guide students to develop their photography and tap into their creativity if that’s there, but I haven’t seen a way to instill that kind of drive. But I did see it in Andy and I know I talked about this in the Warhol book, but it’s where I first saw an artist working and it made a big impression on me. And you know, a lot of art you learn almost by osmosis, that’s the value of apprenticeship. And I didn’t in any way apprentice myself to Andy, but he was very open about what he was doing and he wanted people involved; he would ask people’s opinions and he was doing it because I think he drew energy from people around him. Because of his own working methods and needs, which involved taking in other people, it made his process open to me and to other people. I really learned by seeing an artist work — and he worked every day. He wasn’t sitting around waiting for inspiration to strike, he’s trying things, he’s experimenting. I saw him making decisions, the sum of art is trying things, making decisions, seeing this is a dead end, trying something different, this works, this strikes something in me. So I really got a taste of an artist’s work ethic and working method.

You’re also very generous with going into detail about your processes and what you’ve learned through your own experiments and explorations. There are some photographers who really resist talking about their work, they feel it’s reductive to discuss it. Why are you so open to it?

The simple answer is that I’ve been a teacher for 35 years. And when I started it was very difficult for me because I had spent a long time learning about the mechanical technique of photography and the visual technique, so I understood it, but when I was doing all the experimentation I was doing in the 70s, I never explained it anyone, I never had words in my head. I would think visually, but the visual thinking is silent. If I decide to pick up the camera and move six inches to my left to change the alignment of things, I’m not thinking: “maybe I should pick up the camera and move it six inches to the left,” it just occurs to me and then I do it. I could learn photography that way but it’s completely useless as a teacher, so I had to learn early on how to — to oversimplify it — to take right brain experiences and examine them in the left brain mode so that I could be useful to students. And I love teaching; teaching is as much my life and my profession as photography is.

What’s the best advice you can offer to young photographers who want to do what you’ve done and to have a lasting career?

Well I’m going to direct you to something I wrote. There was a book about, oh I guess it was maybe eight years ago, called Letters to a Young Artist, and the editors of the book wrote a made-up letter from a young artist asking exactly the question you’re asking, and adding to it: do I enter the marketplace and is this going to bastardize my art? They sent this letter to 50 different artists and we were each asked to write a response, then they published the responses without publishing the original letter.

Do you remember the first photograph of someone else’s work that you really loved, that stuck in your head?

We lived in an apartment in New York City and our upstairs neighbor was a very cultured man who was a president of one of the big music publishing companies in the US. He knew of my interest in photography and gave me a copy of Walker Evans’s book American Photographs for my 10th birthday. This was the first photography book I ever owned. I don’t remember what particular picture first struck me, but I know this is the first photography book I owned. I guess the simple answer to your question is, I got this Walker Evans book and it had a big influence on me. And more than just an influence, I would say that I felt some kind of kindred spirit with him. I think it’s a kind of sense of a formal understanding, a classicism that may be inherent in some people. I look at my Warhol work and I compare it to Billy Name’s work and you know we were friends, we were photographing the same events at the same time, and my work just seems so much more classical in approach than his. I think there’s something inherent in people’s personalities.

You’ve been so prolific in your explorations of photography. What’s the most important lesson that you’ve learned about photographic seeing?

I think you may have stumped me. I’m not sure I can come up with one thing. Actually, one thing does occur to me; one thing I find myself occasionally coming back to is questioning visual conventions — whether they are coming from the culture or coming from myself. And some conventions make sense and some don’t. But I’ve always found it useful to question them.

And then you figure out if they’re valid, or whether they’re just empty conventions?

Yeah. To put in terms of grammar: there are rules of grammar, and some of them are inherent in language, the relationship of subject to predicate. But then there are other rules that are culturally accrued that don’t have any actual basis in language, like don’t end a sentence with a preposition. There is nothing inherent in language that says you can’t end a sentence with a preposition. So some rules of grammar are descriptions of the nature of thought, and some are just cultural restrictions. I think there are similar things in seeing. Some of the things we inherit are because this is what seeing looks like, and this is what perception is about, and others are just how people have been trained to organize a picture.

One last question: does beauty have a role in your photography?

That really is a very interesting question. Part of me wants to say no, but I think the real answer is yes. If that makes any sense at all. But I would say that I might find things beautiful that don’t fall into other people’s ideas of what beauty is supposed to be.

Perhaps it’s like what you were talking about in terms of challenging the conventions of seeing. You’re challenging the conventions of beauty.

Yeah, I think so.

Factory: Andy Warhol is published by Phaidon

Credits

Text Clementine de Pressigny

Images by Stephen Shore, courtesy of Phaidon