No longer the brat of British fashion, Alexander McQueen is now a serious propostition: the figurehead of a global brand, a man with a plan. After all he says, doesn’t everyone have to grow up sometime?

Lee Alexander McQueen’s career has been played out perfectly. Of course he has made mistakes and disappointed. But there seems a larger logic, the presence of an unseen hand. And everything, in the end, goes to plan.

This spring he presented the McQueen Fall-Winter 2002 line in the cold medieval dampness of the Conciergerie in Paris. He was finally free of Givenchy and his own label was happily stabled at Gucci. He needed to sum up and move on, he needed to produce a statement of intent. The show opened with a little leather lilac Riding Hood, two wolves – the diddiest monsters, it has to be said – docile and subservient at her heels. You know the thing about Hood: the awakening adolescent, the wolves as sexual predators or the budding sexual impulse. Clever. But that was it for the props and distractions. The rest was just clothes.

I could carry on doing amazing shows, getting lots of street cred. But it doesn’t put dinner on plates. I see McQueen as a luxury goods label. Everyone has to grow up. I’m not Rod Stewart.

Of course, there was an idea. There was tailored tweed with chestnut leather strapping, dandy highway people, naughty schoolgirls and the sexiest sixth formers, leather flasher coats, the glimpse of lace and a sprinkling of avant-gimp gear and thigh-high leather boots, leather bodices and corsets. So here was fetishism turned on its head, made empowerment. Like the Brothers Grimm, McQueen telegraphs ‘a world in which the gentle and the macabre inform each other, and the distinction between romance and perversity is often a matter of perspective,’ said W recently, which has a nice ring about it and sounds right. Shtick though really – and revisited shtick at that. But my God, the clothes.

The collection was huge – 500-odd pieces – and McQueen had never cut so well. The tailoring was of course precise but it was less severe, more inviting. It was immaculately done, clear and consistent and sellable. Here was a story for stores to run with and pieces that would walk off the shelves. I am not a show pony, McQueen said; I’m a player, a serious player. It was the perfect move at exactly the right time. It was what needed to happen.

Strange that those who propose the permanent revolution can become so hard to depose. Strange that, say, a fashion designer, whose job is ephemera – to produce it and propagate the idea of it – should be able to hang on to power and grow rich and old and unimpeachable.

It’s all about corporatisation and critical mass, I suppose. At some point too many people have too much invested in you to let you go down. You have crossed a Rubicon and you are a brand, which means you have armies at your disposal, forces to mobilise. Of course you can still go down but you now have the smell of the long-term about you and the longer you survive, the more you carry the perfume of permanence. There are pressures, to be sure, sometimes unbearable pressures. You have to keep growing, expanding, putting on numbers. The enterprise becomes bigger and more complex but it is essentially geared toward building the idea that life would be so much less for everyone if you were not around. And slowly your position becomes almost unassailable. Alexander McQueen might be about to reach that position.

No longer a young designer or a young Turk or an enfant terrible or anything that might suggest brattishness, amateurishness or impermanence, McQueen is now the hands-on figurehead and chief architect of a ‘global brand’ – or on his way to being one anyway.

You see how it works. Gucci – in a deal that you know about because it caused so much hoo- haa and excitement because these giants, Gucci and LVMH, these sexy luxury goods giants that we are now so interested in, were squabbling and spitting over our Lee – bought a controlling stake in the McQueen label in December 2000. Domenico de Sole, Gucci Group CEO, said: “The questions that I had to ask myself – because it is my job – is does he really have the power and the talent to turn McQueen into a global brand? I think he does; otherwise I couldn’t have done the deal basically.” There is the anointment. And now there is momentum and purpose and there are vested interests. Things will be done to make the ascension possible, if not inevitable. McQueen knows that everything that has gone before leads to this moment, as if predestined. And he is in a state of bliss.

I used to be conflicted about the whole industry. It was quite traumatic, but now it’s not. I have found a company where there’s synergy and at this present time it’s bliss. I’m happy, on an even keel, balanced. Well, still a little off balance I suppose.

After five years tied to Givenchy, McQueen is concentrating on his own name and his own game. And he’s scrapping for his position, which is how he likes it. “It’s like war games,” he says, “and you have to get in there and fight for your territory.” He analyses the market now, reads the FT, checks what rival companies are doing, who is buying what. It’s a corporate thing. It means he has had to grow up a bit, get with the programme. It’s down to him but there are powerful people who need him to succeed. He just has to play this right.

The problem for McQueen during the Givenchy years was that the designer and the showman were forced apart and set to work on different projects. McQueen had little or no influence over Givenchy marketing or advertising. He was there simply to design the collection. And whilst it acknowledged that LVMH saw more in McQueen than a crowd pleaser, the separation of powers led to dysfunction and distortion. Whilst McQueen built a strong haute couture business at Givenchy – if that is not a contradiction in terms – the ready-to-wear collections were too seldom critical successes (though ironically his Spring-Summer 2001 show, when relations with his employers had become openly fractious, was a winner). Without total control, McQueen’s heart just wasn’t in it. “I don’t believe it works. Well, it doesn’t for me. My mind is too focused on my ideal and I can’t do that with somebody else’s collection. Unless you are willing to give up your own collection, I guess, and I’m not.”

This disconnection meant that McQueen’s own collections, impressive as they were, were often lost beneath the theatre, the special effects and Geiger-esque props, the nightmare narratives, the spectral flights and soggy splish sploshing. What was held back at Givenchy was unleashed with tremendous force on his own line. And it was great for press and everyone wanted to be at his shows and ooh and aah but it didn’t make the label much of a business. (LVMH never invested in McQueen’s own line, even though they did make such investments with virtually every other designer in their stable. McQueen says LVMH offered but he refused and later he asked them to invest but they failed to take him up on the offer.) Gucci banked on the fact that, if they offered him total control, McQueen would work out a way of properly prioritising, getting the noise levels right. And McQueen is on message.

“Back in the old days it was easy to be press-worthy,” he says. “You just had girls walking on water or flying through the air. But when Saks and Neiman Marcus in New York are spending £300,000 a season, they don’t want to see girls flying wearing Alexander McQueen – they want to see girls walking down Fifth Avenue wearing Alexander McQueen. It has to be edgy and it has to have that old McQueen feeling but it also has to sell. And people still get the edginess, one way or the other; in the hair, the make-up, the staging. But I just have to keep it real. I’m selling clothes, not the concept of the shows.” McQueen does not see this as compromise but as signs of maturity and intelligence. “I could carry on like that, doing amazing shows, getting lots of street cred. But it doesn’t put dinner on plates. Everyone has to grow up. I’m not Rod Stewart.”

The McQueen label is no longer a side-line or in any way an indulgence or an exercise in shock theatre or media management; it is much bigger and better. There is reason and strategy. “I see Alexander McQueen as a luxury goods label, very modern, very 21st Century,” he has said. “But it doesn’t have to be a global brand to the point of Calvin Klein underwear or billboards.” No, it will be better and smarter and cleverer than that.

And this is where Gucci is smart. McQueen is in a perfect position to build a brand that incorporates all the lessons of the last ten years and so can manage and capitalise on desire in smarter, sharper ways. At the moment McQueen is just so much credibility waiting to be cashed in but it has to be done slowly, slyly. It cannot be rushed and it cannot be over-cooked. It will be luxe and top end because that is the way the market is moving. It will be very special and not at all for everyone, which is the right way to do things. There will be stores – New York, W14th, meat packing district, so right for him, in September; Bond Street in January; Milan in March; Los Angeles next July. But there he will stop, for the moment. “Maybe we will have 15 stores in the long run but I want to see how these shops function in these markets. And they take a lot of investment, a lot of investment. Don’t run before you can walk.” You see how he’s thinking now, thinking about the whole, the total McQueen message.

And so there was also the launch of a bespoke menswear collection in July, made by Huntsman of Savile Row, which fits nicely with all that back-story of McQueen learning his tailoring chops on Savile Row as a snotty 16-year-old, scrawling crude messages, or whatever the truth of it might be, in the linings of Prince Charles’ suits. More myth and message, all part of the whole. And you see how Lee McQueen really is a treasure. And how he gets more valuable all the time.

Ten years ago, London was a different sort of place. Exmouth Market in Clerkenwell for instance still had a market though, in truth, it wasn’t much of one. A bit of fruit and veg and a lot of tat. Mostly there were bookies and boozers serving the posties from Mount Pleasant sorting office across the road who finished their shifts at lunch and had nothing to do but have a flutter on the gee gees and the odd pint, here and there, in between races. There was an Indian, a Chinese and a pie’n’mash shop, a launderette and a hardware shop. It was really like that.

Not any more. Al’s Bar, right on the corner, has had more facelifts than Joan Rivers. And there’s a Starbucks and Pizza Express and Café Kick. There are bookshops that sell big books that look nice on shelves, fancy delis, jewellers of the Jess James sort, antique stores that match the modern with the rococo in that way that is just right and a Moroccan restaurant that has become one of London’s top media troughs. There is always building work and on some sites they are onto the third generation of cous cous-focused eateries or bourgeois knick-knack shops. This is what happened to London.

Lee McQueen has his office just round the corner on Amwell Street and so we sit outside Al’s on the corner, near the benches where the dossers still sometimes gather and scrap and the police sometimes come. Ten years ago he was about to graduate from Central St Martins and his entire graduation show was about to be bought by Isabella Blow. And you know the rest. What excitement there was.

I interviewed him once before, in 1996, just after he started the Givenchy job. We went to his old school in Stratford in the East End in a cab, because his dad and some of his family, as I’m sure you know, are cabbies. Not my idea. He was a prickly over-defensive guy back then who would giggle at his own gags. He has slimmed down dramatically since – he leaves me to go to Space, the top Soho gym – and he goes less for that estate urchin look than he used to. But back then, he had just been appointed the head of a French couture house at the age of 26, which made him the sneering poster boy of ‘Cool Britannia’ and all that. It also made everyone feel that if cool and creativity were the new commodity then our coffers were full and we could bankroll the creation of a new Imperial seat, that this city would be remodelled to reflect the fact that is we were a mighty superpower when it came to darned cleverness. It somehow said all of that. And that is just about what happened.

There is no better place, Lee says of his city. (He likes New York – where he has been spending a lot of time working with architect William Russell on his store – though he can only do it in five-day stretches. “Any longer and they would have to bring me back in a body bag. Or DHL me home, an over-abused body.” He never really took to Paris, or vice versa.) But he is largely invisible here, which seems admirable. He runs with a pack of co-creatives who he hooked up with a decade ago – Katy England, Jefferson Hack and Kate Moss amongst them – but he is by no means a fixture of any sort of social pages.

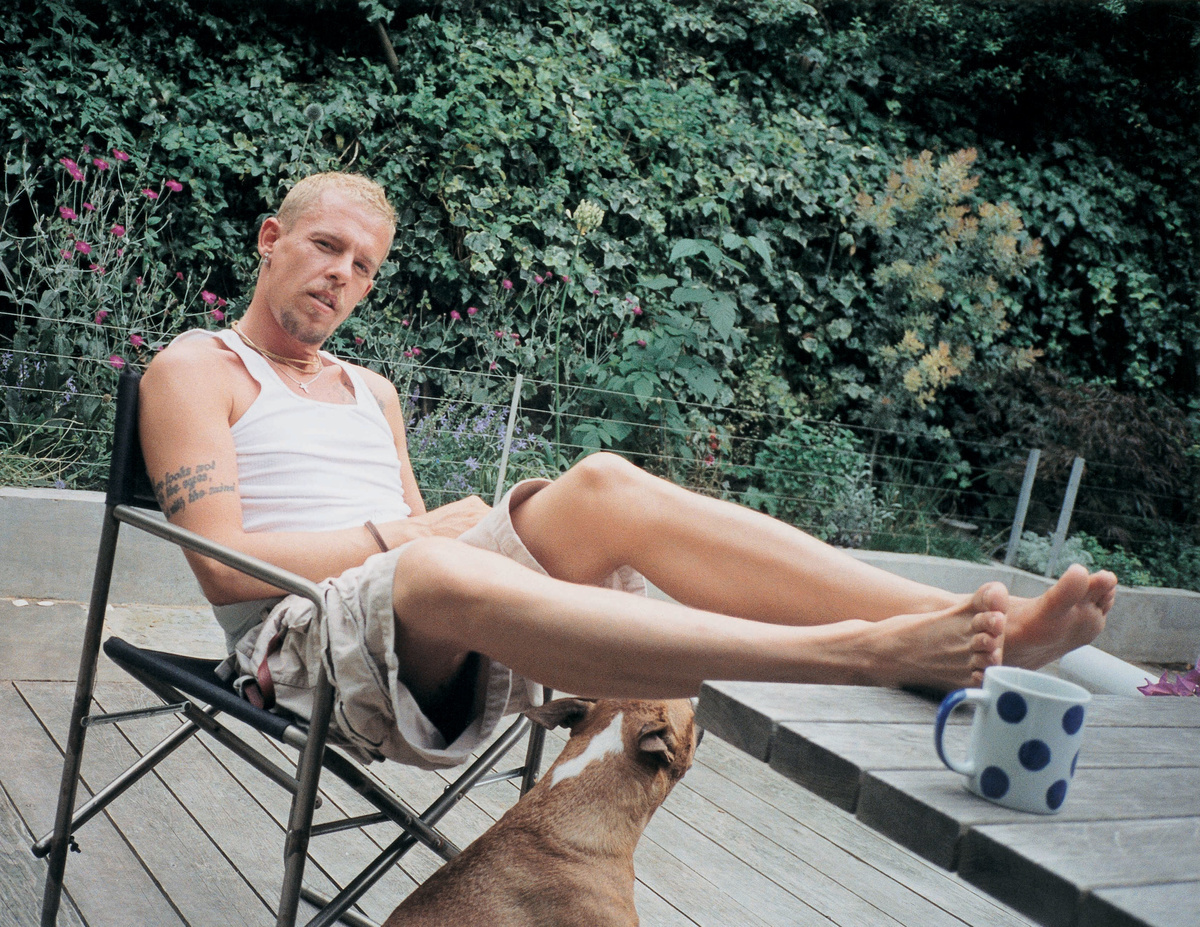

McQueen, now 32, has just bought a 300 year old cottage in Fairlight, between Hastings and Rye on the South Coast. “I can see myself spending a lot of time there,” he says. “It’s somewhere to get out of London at the weekends, otherwise I get sucked in and things go rapidly downhill and you end up going from club to club. The house is a retreat, somewhere to chill out. You can see France from my bedroom,” he adds. “I want to get a canon.”

He seems a little that way, binge and purge, advance and retreat. His Yin and Yang always kicking at each other. He’s an endearingly conflicted character. Whatever plaudits are thrown at him, he still imagines people boxing him off as an inarticulate oik. “You have to tell the difference between the way that I talk and what I’m actually saying,” he insists. “None of my companies has ever gone bust, I employ 50 people, turnover is massive. You don’t get to do that by being a twat, that takes an intelligent person.” I don’t hear anyone arguing with him. “Some of the most brilliant artists in the world didn’t talk posh and didn’t fit in. But a Van Gogh goes for £30m now. It comes down to what’s inside.”

Suggest that now he is Mr Global Brand he will have to sell his lifestyle and he snorts. There will be no Casa McQueen fantasies. “No one wants my lifestyle, I’m telling ya. Do you want to buy my bed sheets? I wouldn’t!” But he wouldn’t have to tell the big lies that some other designers do.

He enjoys a night out, getting nutted, but is openly dismissive of the promiscuous and predatory side of gay social life. “My very first boyfriend introduced me to weird, hard gay sex scenes,” he has said. “He got it completely wrong and it screwed me up. It fucked up a lot of things for me, which I will never forgive him for. Let’s just say it was the complete opposite to the monogamous side of gay lifestyle. And I don’t agree with it.” McQueen is all for monogamy, craves happy domesticity. He wants children. “I want to have a kid and believe I should be able to have a kid,” he has insisted. We talk about kids. Whether to have a boy or a girl. “I like a little princess,” he says. “A bit of Sharon Watts.” However much distance he has put between him and the East End – the proper brutish East End – he remains close to his family. His summer holidays were a couple of weeks in Bali with his eldest sister and her daughter.

A couple of years ago he ‘married’ a 24- year-old documentary film-maker called George Forsyth on a yacht off Ibiza. Jude Law and Sadie Frost were there. Forsyth and McQueen, according to newspaper reports anyway, have since split. He seems embarrassed about the yacht matrimonials, or at least that it was done with a celebrity audience. That is not really his way and he is deeply ambivalent about his fame: “I’m not this LA idiot walking down the street thinking my shit don’t stink.”

The problem, I think, is that his position makes a certain proposition, suggests ways that he should behave. And he goes along with it to a degree but dislikes himself for doing so. He switches between viewing his industry as venal and parasitic and worthy of the greatest passion. Right now though, because of the Gucci deal, he is in a good place. “I was conflicted about the whole industry. It was quite traumatic but now it is not. I have found a company where there is synergy and at this present time it is bliss. I’m happy, on an even keel, balanced. Well, still a little off balance I suppose.”

But if there are conflicts there are also constants, cornerstones. There will always be his dark thoughts and dark history that are made manifest in his shows. “I just use things that people want to hide in their head. Things about war, religion, sex, things that we all think about but don’t bring to the forefront. But I do and force them to watch it. And then they start saying it’s gross and I’m like: ‘Actually love, you were already thinking about all this so don’t lie to me.'”

His orneryness, his refusal to court or kow tow is still there and ultimately winning. (A certain actress can fuck off if she wants a dress from him: “She fucked me over at Givenchy so she can’t have anything else”). There is an intelligence and a knowledge that, beyond his passion for what he does, much else is a crock and that never fails him. And there is a plan to be followed as if written in stone.

Credits

Interview Nick Compton

Photography Corinne Day

[The Graduate Issue, No. 223, September 2002]