The art world sees itself as avant-garde and progressive, but in reality, it remains as corrupt, patriarchal and white as the conservative governments it often critiques. It’s funded by billionaires that have made their money in nefarious ways: selling weapons of state control, investing in for-profit prisons, fossil fuels and opioids, or securitising student loans. It’s about the accumulation of wealth, with money at the top and exploitation at the bottom, a few people having it all and manipulating the market. “Everything that’s wrong with capitalism is really wrong with the art world too,” says Käthe Kollwitz, a founding member of the Guerrilla Girls, a group who’s revolutionary history is documented in the new book The Art of Behaving Badly.

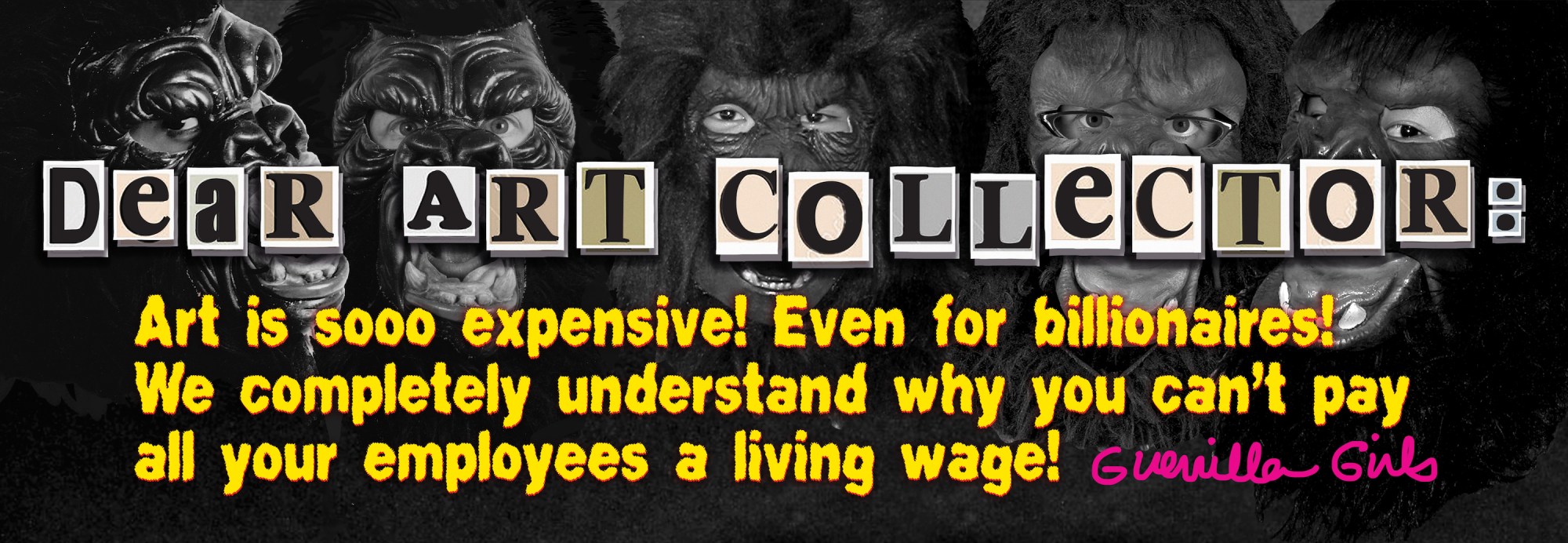

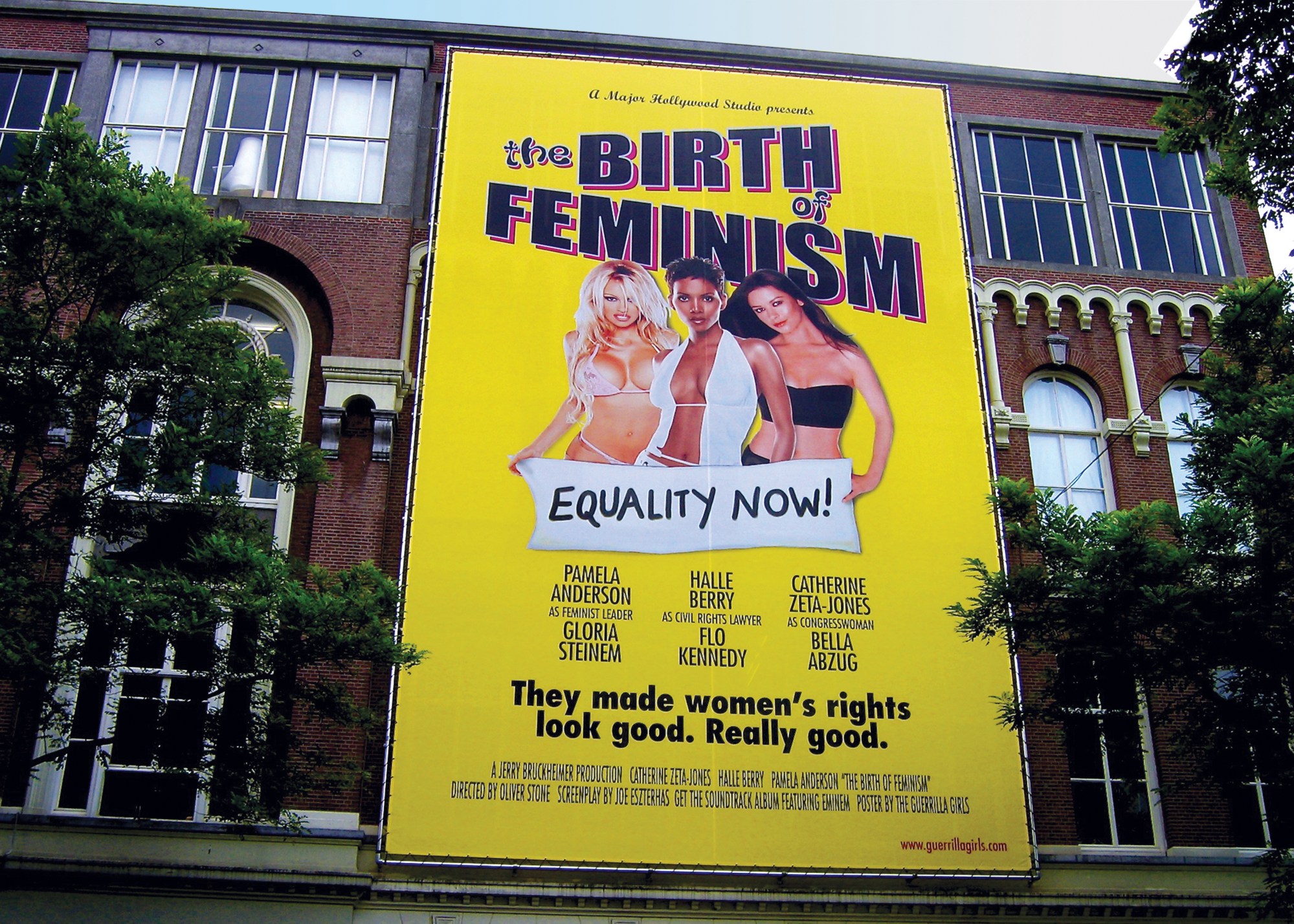

Since 1985, the Guerrilla Girls have been disguising themselves with gorilla masks and pseudonyms — Kollwitz takes her alias from German painter and sculptor who was an advocate for women’s rights and equality. The group punks people and institutions with their changing collective of up to 60 artists, plastering posters on the streets that expose the racism and sexism of the art world and society at large. They hone in on wealthy art collectors who not only drive the market but also sit on the boards of important museums so that their presence also “pollutes that part of the art world,” explains co-founder Frida Kahlo. “If we want to aspire to a more democratic world, we need to get away from the idea that the art world is about the taste of the rich and powerful.”

Art has always been a status symbol for the ultra-wealthy — a trophy for collectors competing for brand name artists. “It turned into an Olympics,” Kahlo says. “Only one person can win and everyone else is a loser. But culture is a much richer story than that. Culture is all about the failures. It’s about diversity, it’s about things that go against the mainstream. Everyone’s vision of history is different, it’s an ongoing argument. The idea that the market can identify what art is the most significant is a little crazy.”

Yet as a result of the post-financial crash era, collectors have more money than ever before. They are the real tastemakers, choosing which artists to invest in and what hangs in museums. Even as global sales plunge due to Covid-19, Sotheby’s recently sold a Francis Bacon triptych for $84.6 million. Last year, a 1989 sculpture by Jeff Koons sold for $91.1 million at Christie’s, becoming the most expensive work sold by a living artist, and in 2017, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman purchased a Leonardo da Vinci painting, Salvator Mundi, for a jaw-dropping $400 million.

What statistics also show is that the art world is far from gender parity. In the past few decades, only two works by women have ever broken the top 100 auction sales for paintings. The Guerrilla Girls have been telling the world that for the past 30 years. They formed in response to a MoMA show in 1984 titled International Survey of Painting and Sculpture, that featured 169 artists, featuring only 13 women and even fewer artists of colour.

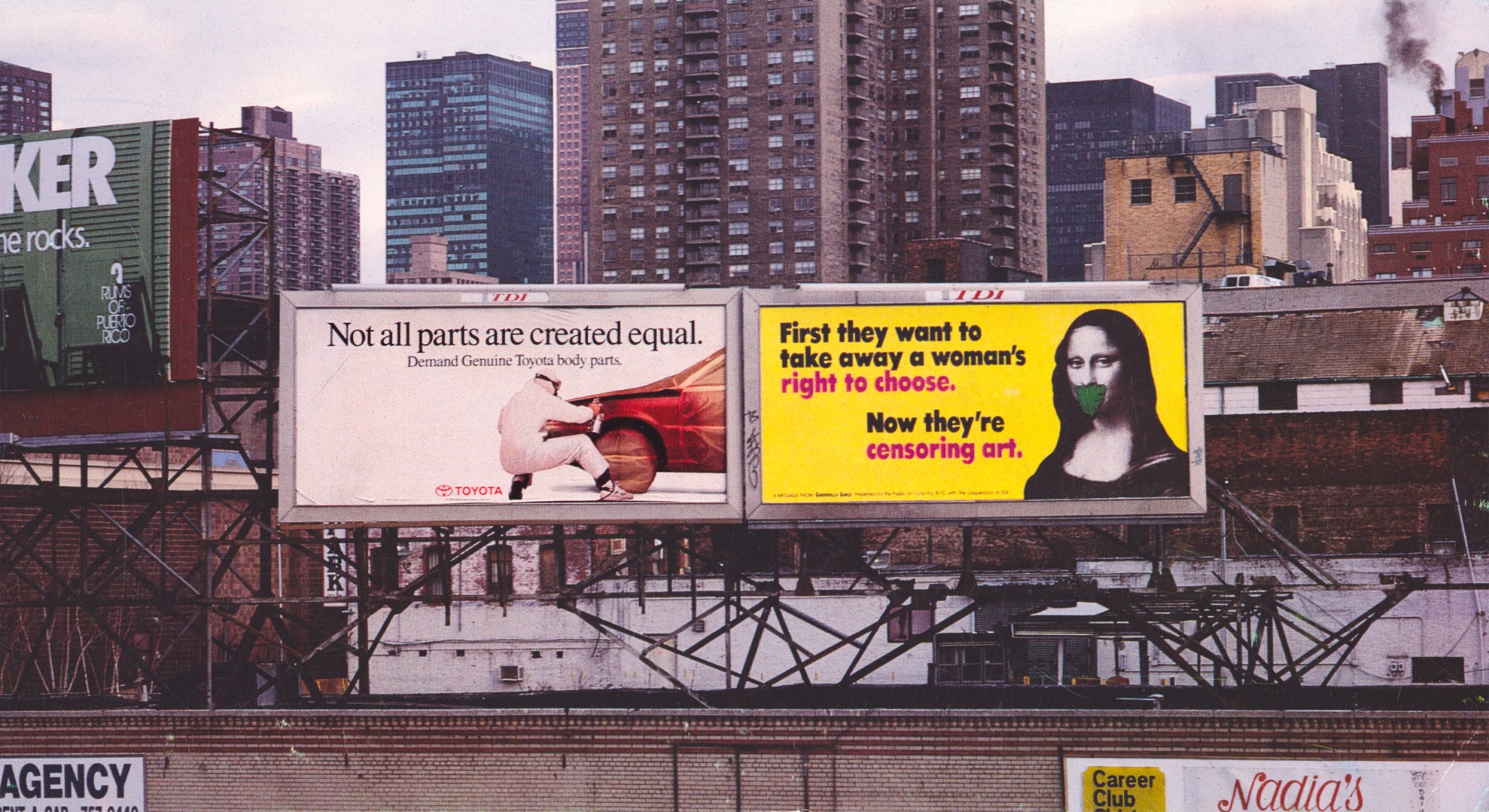

They took to the streets of New York City with data-driven posters that showed the lack of diversity in the art world, naming and shaming art galleries and museums that were completely devoid of women. “We sell white bread,” one sticker read. “Ingredients: white men, artificial flavourings, preservatives. *Contains less than the minimum daily requirement of white women and non-whites.”

In 1989, for the price of one Jasper Johns painting that sold for $17.7 million, the Guerrilla Girls reported that a collector could have bought the work of 68 women and artists of colour. They asked, “When racism and sexism are no longer fashionable, what will your art collection be worth?”

Every year the Art America Annual would publish a list of the artists featured in galleries, which the feminist collective would mine for killer statistics, reinventing political art with bold visuals and disruptive advertisement-like headlines. “It was a breath of fresh air, somebody speaking up for artists in a totally new, unforgettable way,” Kollwitz says.

The artists’ style of protest has become both timeless and museum-worthy. One of their most iconic prints has been hung at MoMA, the Whitney Museum and the Tate. It asks: “Do women have to be naked to get into The Met museum?” above the gorilla mask-clad, reclining naked woman from Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’ painting La Grande Odalisque. The artwork is accompanied by the facts: “less than 5% of the artists in the Modern Art Sections are women, but 85% of the nudes are female.”

The Guerrilla Girls argue for a new structure that frames art not as an elite commodity, but something everyone can share — like music, dance or film. They sell their posters for $30 apiece, their books are consciously cheap and they are happy that their work is infinitely reproducible. Everyone that owns one of their posters, owns the same object whether you’re a student in a dorm room or a wealthy collector.

In the three decades since the group was established, the art world has changed for the better, but there’s still a long way to go. “No one would argue now that you could tell the history of art or the history of American culture without the voices of women and people of colour,” Kahlo says, despite the fact that the fight for equality in the art world is still ongoing. More and more artists are demanding to be paid when museums feature their work, and the internet has become a helpful tool to hold large institutions accountable. “We are trying to shame them into doing that more and more,” Kollwitz says. “There are fantastic artists out there and we’re lucky that artists are devoted to their work and will do it, whether they get recognition or not. Otherwise, we’d really have no culture.”

Ten years ago, the Guerrilla Girls posted flyers around the Los Angeles County Museum of Art protesting one of its donors, Eli Broad, whose collection, at the time, was all white and male. Now that’s totally changed. He created his own museum in Downtown LA that features a diverse range of artists. “Where do you think he got that idea?” they ask.

“But we haven’t been able to change the economic structure of the art world,” Kahlo says. A structure that’s entrenched in patriarchal values and racism — where curators, collectors and gallery representatives are disproportionately white and male. It leads to a cultural bias of art interpretation, and gives rise to male artists that are not held to account for their actions. When you start to analyse the behaviour of celebrated male artists — Picasso, David Smith, Hans Hoffman, Lucian Freud — it’s clear that male domination and violence against women has become part of the aesthetic of Western art and culture.

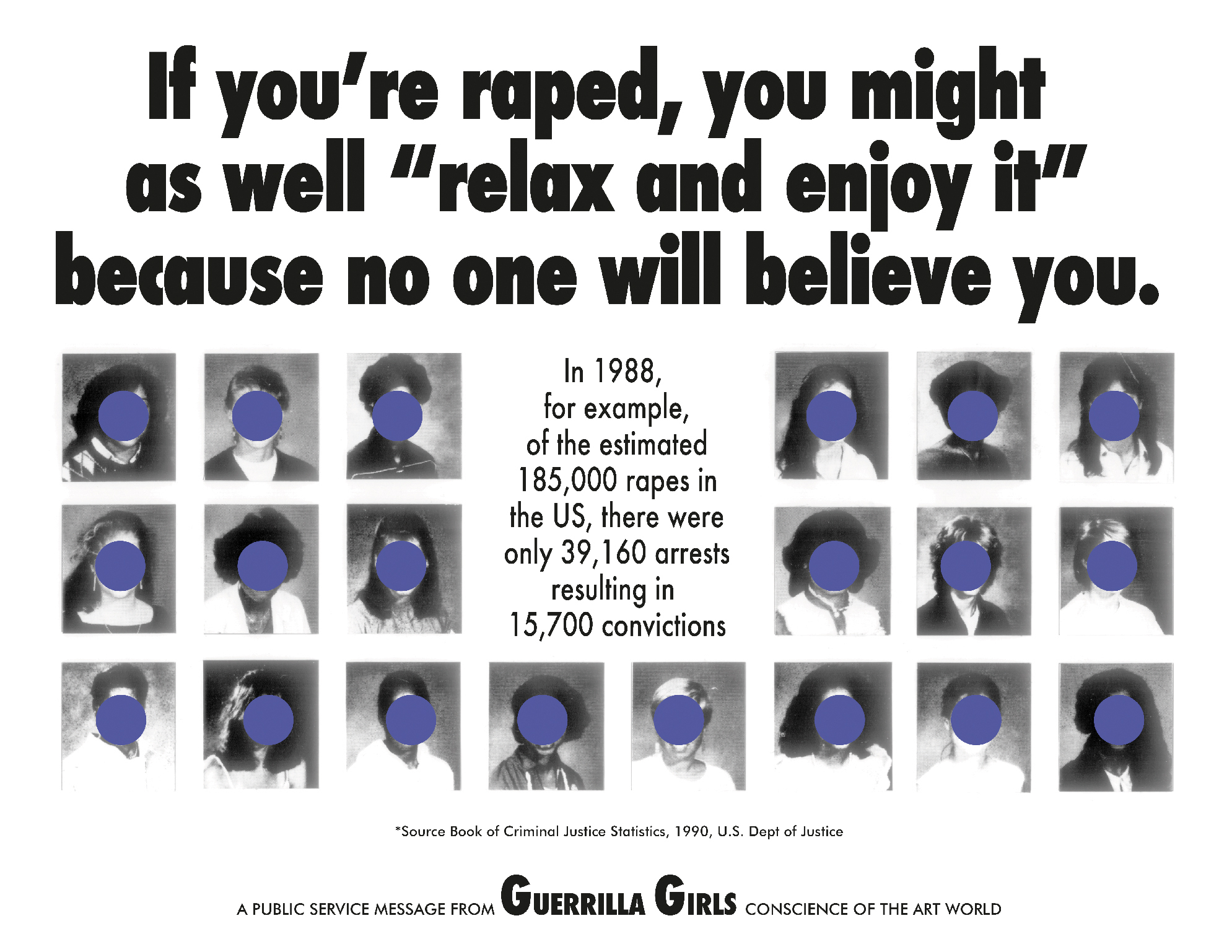

As a result of the #MeToo movement, “we’re now thinking about sexual assault and sexual harassment in a way that hasn’t been looked at before, from the point of view of the survivor,” Kollwitz says. “But there are depictions of women, in mythology and the Bible, of sexual assault as an aesthetic in art.” The problem is, Kahlo adds, “a lot of people thought that art lived in its own realm and its own world and it shouldn’t be scrutinised by the rest of the world.”

One of Guerilla Girls’ more recent images calls out Chuck Close, who was accused of sexual harassment by several of his portrait models. He painted President Clinton’s portrait, which hangs near Michelle and Barack Obama’s at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington D.C. The artwork suggests three ways to write a museum wall label when the artist is a sexual predator. The Guerrilla Girls are not calling for the artwork to be removed, but believe this deserves to be more than simply a footnote. “We think it’s a major theme in the development of the persona of the modern artist,” Kollwitz says.

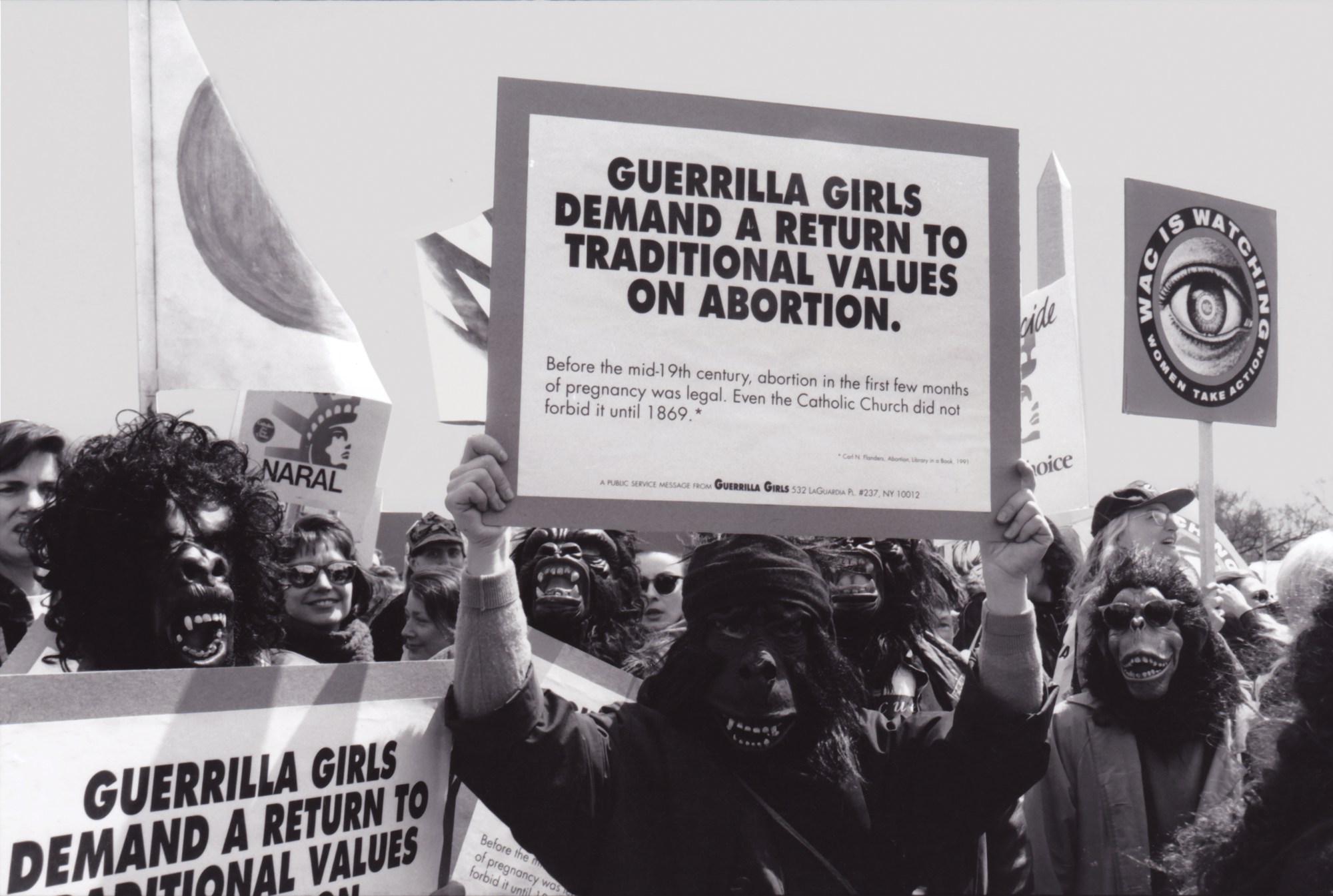

The Guerrilla Girls’ critiques have been very visible throughout history, from Ronald Reagan’s reversal of abortion rights to his cutting of public funds that left homeless people without food, shelter and medical care. The posters target systemic racism, homophobic laws and white supremacy in the 90s, and sexism within the film industry through today. The Guerrilla Girls have been the conscience, not just of the art world, but of culture more widely. They remain active, supporting the Black Lives Matter movement and calling out museums with financial ties to Jeffrey Epstein, but for the most part, they’ve avoided a direct attack on Trump.

“If you look at our work, you’ll realise that we’ve been pointing out Trumpian values in the art world for a long time without even talking about him,” Kahlo says. “We’ve been talking about things in American culture that have given rise to Trump. If you look at the art world, it’s always been about money laundering, it’s been about tax evasion, it’s about exploitation at the bottom and all the wealth at the top.” But, Kollwitz adds, “with a lot richer people than he ever was.”

Guerrilla Girls: The Art of Behaving Badly, published by Chronicle Books, is the first book to catalog the work of the Guerrilla Girls from 1985 to today. It can be purchased here.