At the beginning of the millennium, Schwipe was everywhere in Melbourne. Initially a T-shirt brand established by Tim Everist and Misha Glisovic, it developed into a full fashion label and a second skin for the city’s Rave Juice fuelled club kids. At the centre of the brand was their concept store and gallery Don’t Come, hidden away at the top of a rickety staircase it was more welcoming than it looked. Before smartphones or social media, it was a place to hang out, meet friends, discover new brands and drink obscene amounts of beer. The brand folded in 2009, a casualty of the Global Financial Crisis and general exhaustion. This year they re released their cult Islam is OK! t-shirt, launching a wave of bittersweet nostalgia. We look back at the low-key beginning, booze soaked middle, heartbreaking end and possible future of one of Melbourne’s favourite labels.

THE BEGINNING: In 1999, Melbourne could feel like the end of the world: the internet wasn’t yet ephemeral, international travel was expensive and ideas disseminated more slowly. Feeling the lag over being able to access another country’s scene, Tim and Misha decided to create their own.

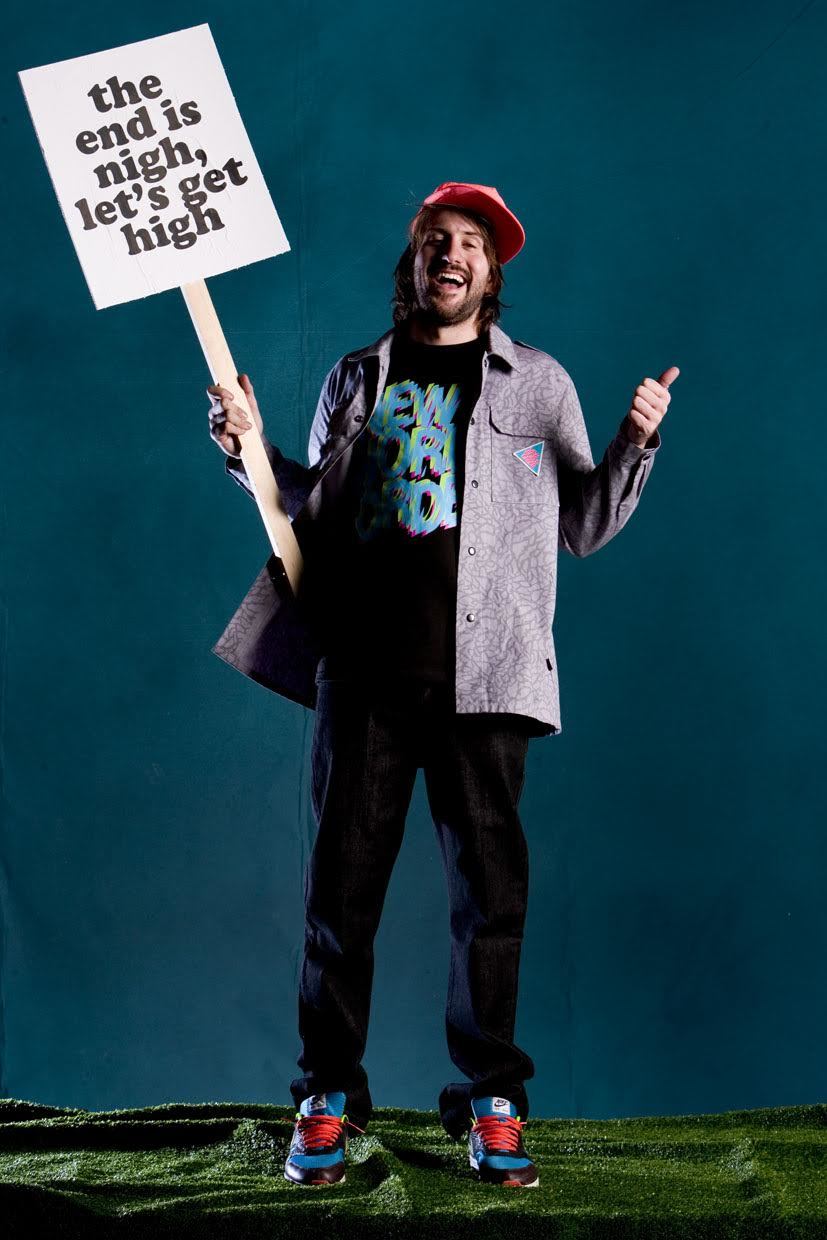

Tim (Co- founder): Schwipe started around 1999, inspired by the threat of Y2K and impending doom. We felt the only way to combat this civilization ending dilemma was to release a collection of t-shirts. Also I couldn’t find any brands I liked. I started with Darren Cross (of the band Gerling), Misha then became involved and made it better.

Dan Whitford (Friend of the brand, member of Cut Copy): Originally the label made noise from a relentless wheat pasting assault on the Melbourne inner city. This was a time before “street art” existed as we know it, at the time this was an original marketing strategy. They once wheat pasted the black doberman on the Chanel store in Harajuku Tokyo

Misha (Co- founder): It was a very different time as far as internet shopping: you could only get brands from the States and Japan when friends went overseas.

Tim: I grew up with brands like Vision, Mambo, Rip Curl and Quicksilver which all had really crazy, bright, amazing graphics. I wanted to do something like that, I didn’t really have a plan, It was just like, fuck let’s do some cool shit. They were stupid ideas, we had a laugh doing it, it was just a bit of fun. But everyone loved it and were really supportive of the fact we were Australian. There were lots of local designers starting to make new things and lots of new cool retail stores to support the scene.

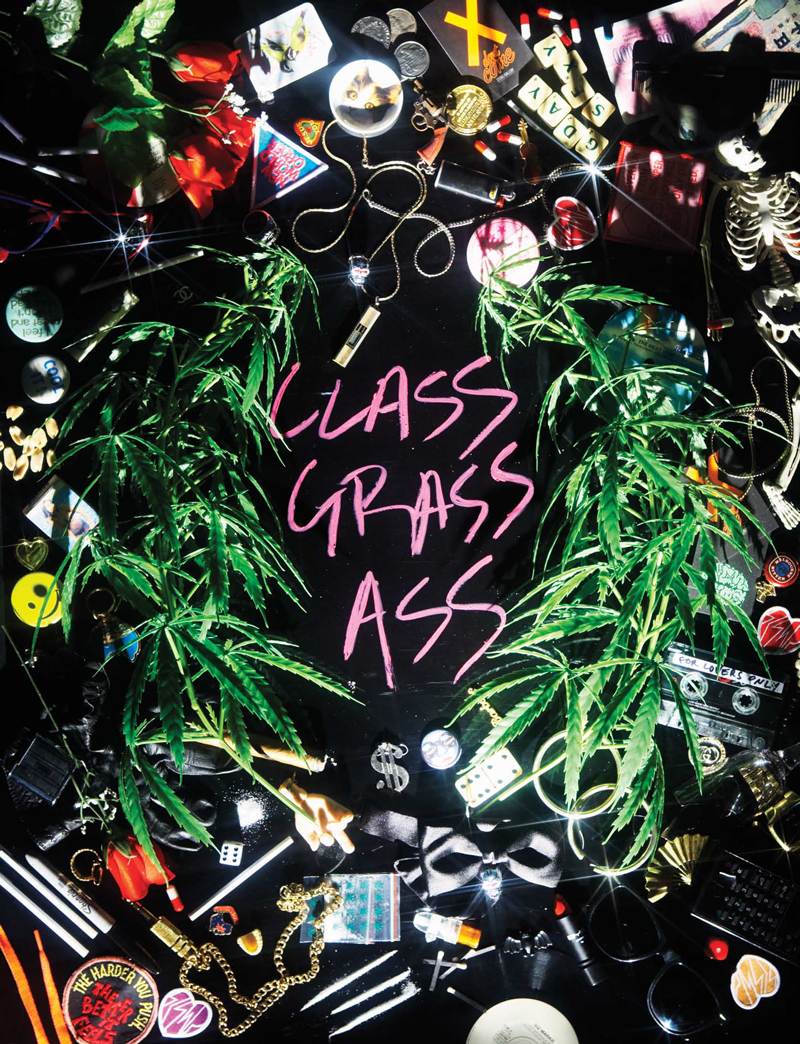

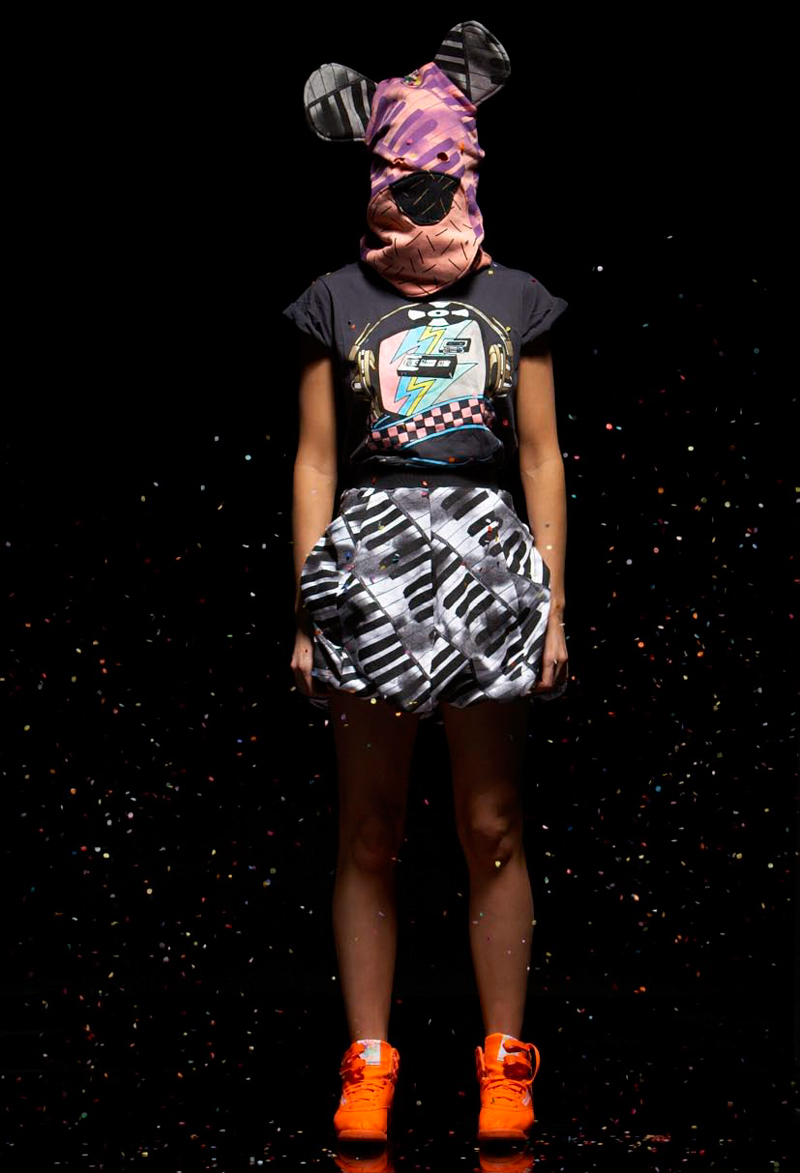

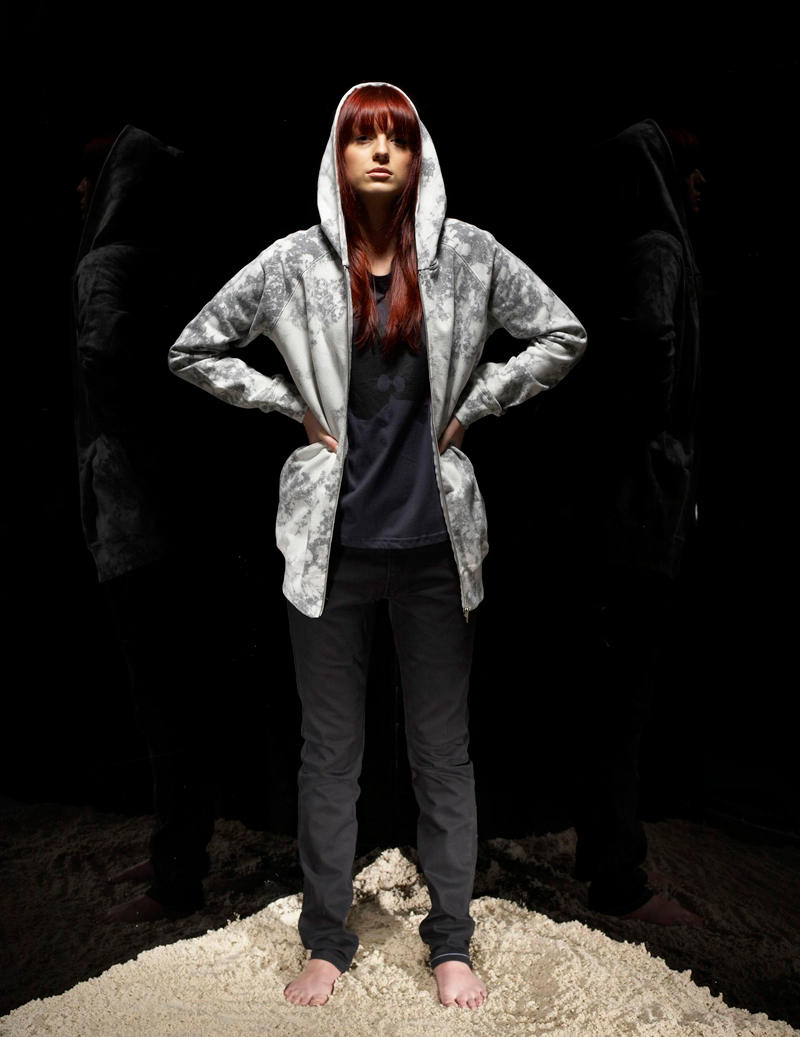

Elizabeth De La Piedra (Don’t Come employee): Schwipe offered an aesthetic that represented the culture, whether it be references to “Islam is OK!” or brain melting “rave juice graphics. It was cohesive.

Tim: Our theory was if we don’t want to wear it, we don’t make it. We injected our personalities into everything – whether it was our attention deficit disorders or the appreciation of a good drawing.

Misha: We saw something happening in Melbourne, people from different creative fields starting to hang out together and do stuff. We did a range, New World Order, where we got Cut Copy, Avalanches and Presets to do a 10 second sound loop for us.

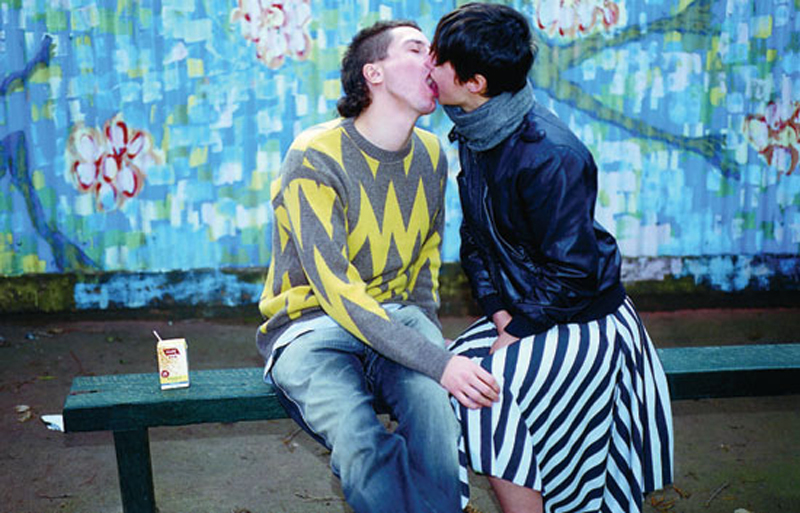

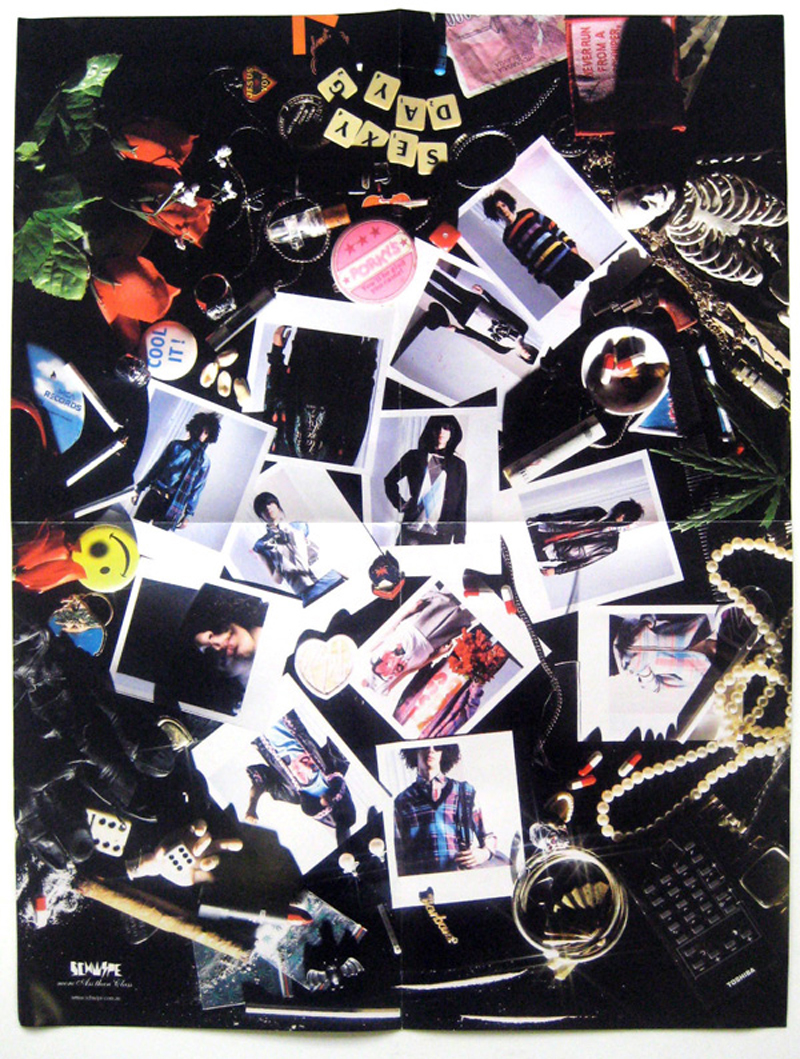

Tim: Rhys Lee was huge influence upon the brand…all his crazy drawings and designs really shaped the brand early on. Then there was collaborations with photographer Cory White who soaked up the essence of Schwipe for the look book shoots.

DON’T COME: During Schwipe’s early days Melbourne retail was thriving, as small independent stores served as places to hang out, party and meet people. Their piece of this was Don’t Come, opened in 2006 it was a concept store and gallery that became a beloved social hub.

Tim: It was in a really awkward place up a staircase in an old, historical building so we didn’t get random people wandering by. The people that did come were there for a reason.

Tyson O’Brien (Don’t Come employee): When I was 18, going out every weekend, I kept bumping into this dude wearing crazy track pants with barbed wire on them and cool t-shirts. That happened to be Tim, we became mates and when the boys opened Don’t Come I was lucky enough to be given a job. You’d see the same kids come back asking when the new season was dropping after they’d bought the whole previous one. It was awesome how the boys connected with the youth and the kids help develop the brand.

Tim: We wanted to create something different, like the retail spaces we’d visited overseas. It was such a massive space in the city, there’s nothing like that nowadays. A lot of our friends were artists who had shows there, it just all kind of came together.

Misha: Having the shop was my highpoint: doing exhibitions there, bringing artists out from overseas and throwing monthly parties with all our friends. We were trying to create somewhere our friends and customers could hang out, and bring things out that people wanted to see and artists people were into. We were trying to make something.

Elizabeth: I loved the creativity and the constant attention to reconceptualising the gallery space for the different artists that would come show there.

Dan: The store was an amazing space and really elevated the brand, it was like how the fuck did you guys get this place happening, it was impressive

Tyson: Half art gallery, half store, loud music, heaps of mirrors -which were a pain in the ass to clean. There were so many parties, and every time a festival was in town you’d have the biggest artists in the world coming to check out the store to skate and chill. Insert Kanye and Lupe Fiasco.

Tim: Kanye came in one day in 2007. We were one of the first brands in the world doing the all-over print thing, he and his crew fucking lost their shit over it. We were pulling out all this old, dead stock from out the back for them, like, “who the fuck are these guys?” It was madness. It was when he was starting to think about doing his brand Pastelle, he asked us to do designs for him. We went and met at a recording studio to talk about it. He went to give me a high-five and I left him hanging, that’s my claim to fame, leaving Kanye hanging. Misha went on to work with Kanye on a clothing line, going to Japan to collaborate with Nigo from A bathing Ape, but nothing ever came of his original Pastelle brand.

THE SCENE: Beyond their Kanye moment, the brand was inspired by the people around them. Counting Cut Copy, Midnight Juggernauts, the Avalanches and the Presets as friends, Schwipe became a uniform for party kids. “All of our friends were musicians, DJs or graphic designers, everyone seemed to be doing something creative,” Tim remembers, “I’m not sure what our place was. Perhaps agitators.”

Elizabeth: Schwipe was during the peak of the Ed Banger / Bang Gang period, as nightlife in Melbourne shifted from rock to electronic — they were definitely a part of that, DJs would rep a lot of the pieces.

Tim: We used party all the time at Honky Tonks and Third Class, everyone got fucked up. It was all intertwined because that’s when bands like the Presets and Cut Copy were really popular and we were all just mates. I guess a lot of the designs were party orientated, weird, crazy kind of things.

Tyson: Everyone that wore Schwipe was a little out there, cool and had a good sense of humour, not to mention the guys seemed to be friends with every cool band at the time — Cut Copy, Presets, Midnight Juggernauts, the Avalanches and they were all repping.

Dan: They were directly involved in that scene in Melbourne so it was honest, it was a small community so you couldn’t fake it like today, people would know you and see you, so you couldn’t invent a brand or a look or a story

Schwipe street art over the decade.

THE END: While life and business seemed golden from the outside, the brand was struggling. Tim and Misha were in their early 20s when they started, and never planned to run a full company. While cultural success flowed, financially things were more complicated.

Misha: We were doing it for fun and having a great time with people we liked, then it grew into a business that neither of us had experience in running. It got serious when we had to start thinking about ranges, and not just doing whatever we felt like. We didn’t get into it because we wanted to run a fashion label, we just wanted fun stuff to wear.

Tim: The most successful points for us were the all-over prints, economically it was more cost effective to print hundreds of metres of fleece. But then the whole all-over print thing died in the ass, I guess we were just riding a trend.

Misha: There was a point where I was thinking, fuck I’m not even wearing any of this stuff anymore but we’re still making it. I don’t know if we got stuck doing what we were doing, but mentally that was the beginning of the end. When you’re not your own audience what are you doing? The market turned away from our style, but maybe we should have turned with it.

Tim: Things became a bit weird in Australian retail, it was around the GFC, stores started closing and it was hard to get paid. Creating your own viable business is a really hard thing to go and do. I don’t think Schwipe was ever really that viable. I was stressed and under pressure the whole time, so I didn’t really appreciate it. We were always on the verge of being successful in terms of making money. I was always pissed that we never made any. We always felt we were so close, but we just didn’t get there.

Tyson: It was fucking sad! I literally wore nothing but Schwipe for years, I had no idea where to buy other cool shit from. The brand was a big part of my identity: I was the skinny kid, with long hair always wearing Schwipe.

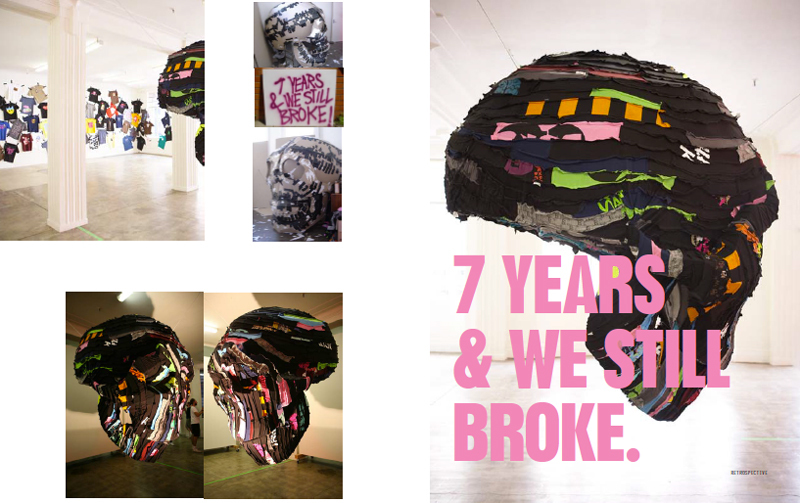

Tim: We planned the end a year and a half before because we had to fulfil the three year lease of the store. The last was called “BOOZE DEBT DIE”, kinda summed up the whole thing right? We tried to take on the world, and all we got was Tasmania!

Tim: I didn’t perceive what people thought of it until the end, I was in my own world. We had a closing down sale and everyone was crying, people were so upset, we got so many nice emails, everyone was so supportive.

Dan: When other labels and stores in Melbourne took themselves seriously these guys didn’t really give a fuck, they made what they liked not what they thought they had to. It was more fun.

Misha: Schwipe was always a young brand, and a great to be involved with when we were in our 20s. There was a lifestyle associated with it — going out, partying, having a good time — as we got older it was time to move on. I wasn’t so sad.

Tyson: I still wear a whole bunch of the old shirts! Schwipe was ahead of the game, I’m stoked they’re back, hopefully kids will see how future forward the boys were!

Tim: Doing these t-shirts, Misha and I were like, “Is anyone going to buy these? Is it going to be embarrassing for us?” People were constantly writing stuff on Facebook (asking for the reprint), were like, “at least those people will buy a t-shirt.”

Dan: In 2016 people are looking at more optimistic artwork and fashion, it’s time to have fun and escape the pressures of our day to day existence, Schwipe should provide some relief.

Tim: It’s great seeing people still wearing the stuff like 10 years later. It’s like it’s still dead but kind of alive, it’s back from the grave.

Misha: It’s funny seeing it in op shops or on younger kids in the street, I thought it would have been forgotten by now. Tim said that of all the new orders, extra large is the most popular size. I don’t know if that’s a reflection on the fashion today or how fat our customers have got.

Credits

Text Wendy Syfret

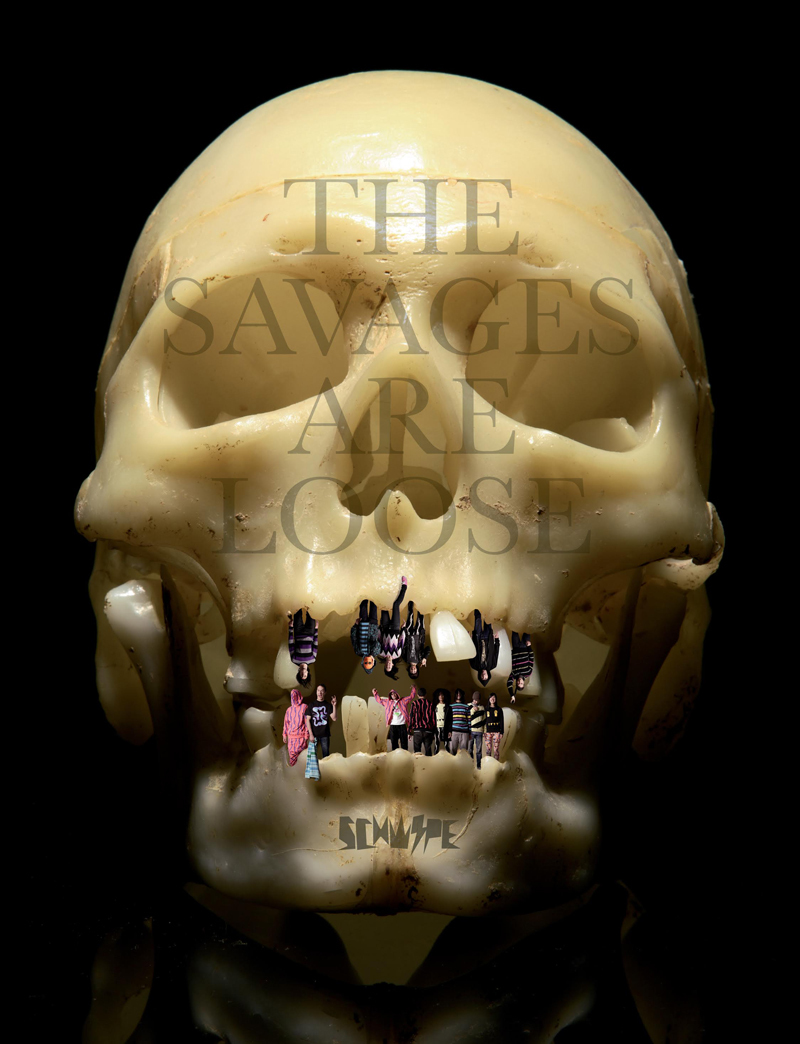

Images via Tim Everist and Misha Glisovic