Whenever artist Angie Pai makes a move in Melbourne’s creative underground, she creates ripples in the city’s independent fashion and art scenes. One half of popular local label PAI, her solo work consists of grand scale installations, illustrations and embroidery. In the past she’s kept her subjects light, exploring aesthetics rather than venturing into social commentary. But this year, she’s moving in a more personal direction and bringing a social, political and emotional emphasis to her creations.

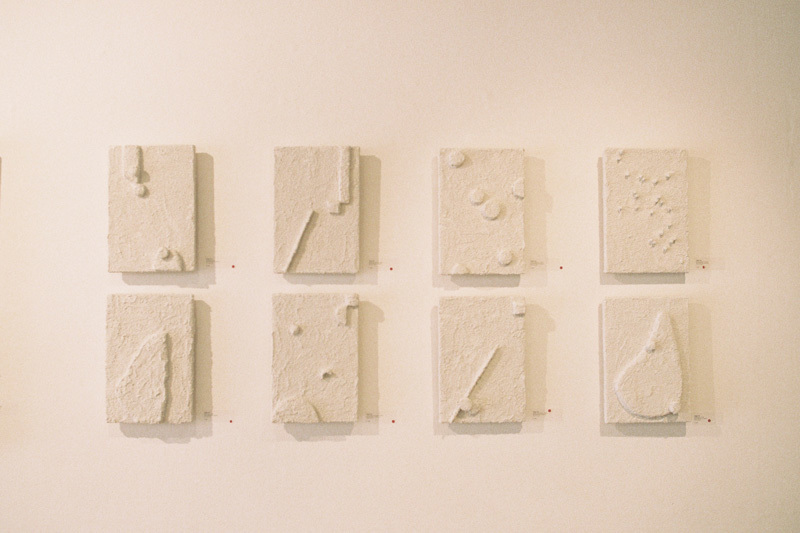

Her upcoming show Silence Doesn’t Work for Me is a response to her own family history, and an effort to connect to her parents’ past. With brutalist concrete and sand sculptures placed in delicate hand-made frames she’s questioning societal privilege and the complacency it generates. The subject came to her after learning about the hardships of her parents faced after migrating from Taiwan to Melbourne in the 90s. Like many migrants in Australia, her parents suffered financially and emotionally to give their children a better life. Unable to find an eloquent way to express her gratitude to them, she uses her art to not only thank them but recognise her responsibility in helping others who are replaying their plight in 2017. In reflection of this, 100 percent of profits from Silence Doesn’t Work for Me will be donated to the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre.

How did Silence Doesn’t Work for Me come about?

The concept for this show metamorphosed quite fluidly last year when I was feeling more absent than usual. I had a dire need to contribute socially, to be more culturally conscious and to make a positive impact. It’d been a big year, a really rough year. Through discussions with my parents day in day out, I learnt a lot about the hardships they went through while migrating to Australia.

For a while, I would sit on my bed and cry every night. I had so many emotions, and I didn’t know what to do or how to deal with them. Then a good friend of mine said, write it down, express it, don’t just sit there and cry for god’s sake, do something with it. So I did.

Can you tell us a bit about these hardships you’re paying an homage to?

My parents grew up in country towns in Taiwan. In their early 20s, they didn’t have much money, but they would spend it all on finding a better home for their future family. My dad was studying to be a textiles chemicals engineer, and working double shifts in a factory as the fees and costs of immigration for an entire family would rack up a huge bill. Eventually, troubles at work forced dad to quit his job days before the birth of my older brother. He told me, “All of a sudden I had nothing to lose, yet also everything to lose. I just had my first child and I had no job”.

He saved the equivalent of $400AUD and started his own textiles chemicals company. I remember him telling us about being so broke he didn’t know whether to feed himself or to buy my brother a little toy. Mum and dad built the business to a stage where it qualified for permanent residence in Australia. I’ll never understand how they did it, but I’ll be forever grateful they did. Mum and dad are the bravest and kindest people I’ve ever known. All of these are themes I wanted to explore in the exhibition.

Alongside your parent’s personal story, you explore ideas of social complacency and privilege. Why did you want to touch on that too?

It wasn’t really a choice, it was all I could think about. I was living with the guilt of feeling privileged, yet totally useless, everyday. I want to look back on my life one day and know that I’ve contributed in a way that makes me proud of who I am. I had this fire burning within me to scream and shout about all the things that just aren’t okay, it became impossible to stay silent. I wanted so bad to give back.

A lot of what you’ve said seems to hang on this lingering sense of guilt over never having to go through what they did. Is that fair to say?

I never really had grasp on the realities of my parent’s upbringing. I’d seen the houses they grew up in, but everything is normalised as a child. Revisiting my parent’s childhood homes as an adult was a confronting experience. Reading about immigrant struggles was confronting. Our entire lives, my parents strived to provide my brothers and I with what they saw to be their dream lives. When I finally knew and understood that, all I could think about was how lucky I was, and how my life could have easily been very different.

You’ve obviously realised a lot about yourself through this show, but what are you trying to express to others?

I think it’s easy to become complacent within a privileged society. Last year we saw how impossible feats, both positive and negative, can be achieved on a world stage. On a substantially smaller level, each of us can do this within our local community, to combat issues that don’t sit right. I believe the more you do, the more you want to do, and the more others want to help you.

‘Silence Doesn’t Work For Me’ is on between 7 and 11 January at Metro Gallery, High St Armadale, Melbourne. All proceeds will be donated to ASRC.

Credits

Text Alex Manatakis

Photography James Robinson