Is there anybody more desperate than a 26-year-old who wants to be an artist?

This is the question Anika Jade Levy’s debut novel Flat Earth, out now from Catapult, strives to answer. It follows Avery, a graduate student and aspiring writer at an elite institution who pays her tuition by working for a right wing dating app and having sex with wealthy men.. She snorts stimulants, makes a blood pact with the glass of her broken phone screen, and nurses jealousy over her wealthy, more successful best friend Frances, who, over the course of a single year, makes a successful documentary about conspiracy theorists in rural America, gets married, and becomes pregnant. It’s a lean novel of bone-dry prose that is best relished on a sentence level: “Why was I always seeking permanence in places where women are disposable? Like galleries.” Levy writes. Reminiscent of the wry reportage of Elizabeth Hardwick’s Sleepless Nights and the moving metafiction of Ben Lerner’s 10:04, Flat Earth is a very now New York novel that in its palpitating heart is about a young woman determined, at all costs, to remain porous.

Levy is a founding editor of Forever Magazine, which is commonly associated with the very 2021-2023 Lower Manhattan artistic scene that the novel skewers. It’s easy to talk about Levy’s apt descriptions of a bereft ecosystem of tradwifes, incels, male sculptors, gallerinas, and “sea of pleated skirts on rail-thin girls” who descend, in every generation, into the Lower East Side. The flatness, rendered by apathy and self-interest, are intentional choices :“Everyone in this book is really two-dimensional—I wasn’t interested in writing nuanced female characters,” Levy told Cultured.

But what’s more interesting than that flatness is how Levy parlays it into vulnerability—the deadly third rail of the novel is the desperation that causes its characters to take up Catholicism, antiquated ideas around female domestic labor, as well as right wing dating apps, casual sex work, even going so far as to build their own FiDi bunkers. The apple may be rotten but its core remains intact—the vulnerability of a meandering 26-year-old desperate to finish her book, to be loved, to forget her father and forgive her mother, to be brought into the light by a husband, by literary ambitions, by anything. This vulnerability feels rare in an increasingly transactional world. It can, in fact, only be accessed through a porosity that is socialized out of you the longer you participate in an artistic ecosystem driven by ego and scarcity. That ecosystem makes friendships particularly complicated—and Flat Earth’s core relationship between Avery and Frances is its most interesting, as it pushes and pulls the levers of female artistic friendship.

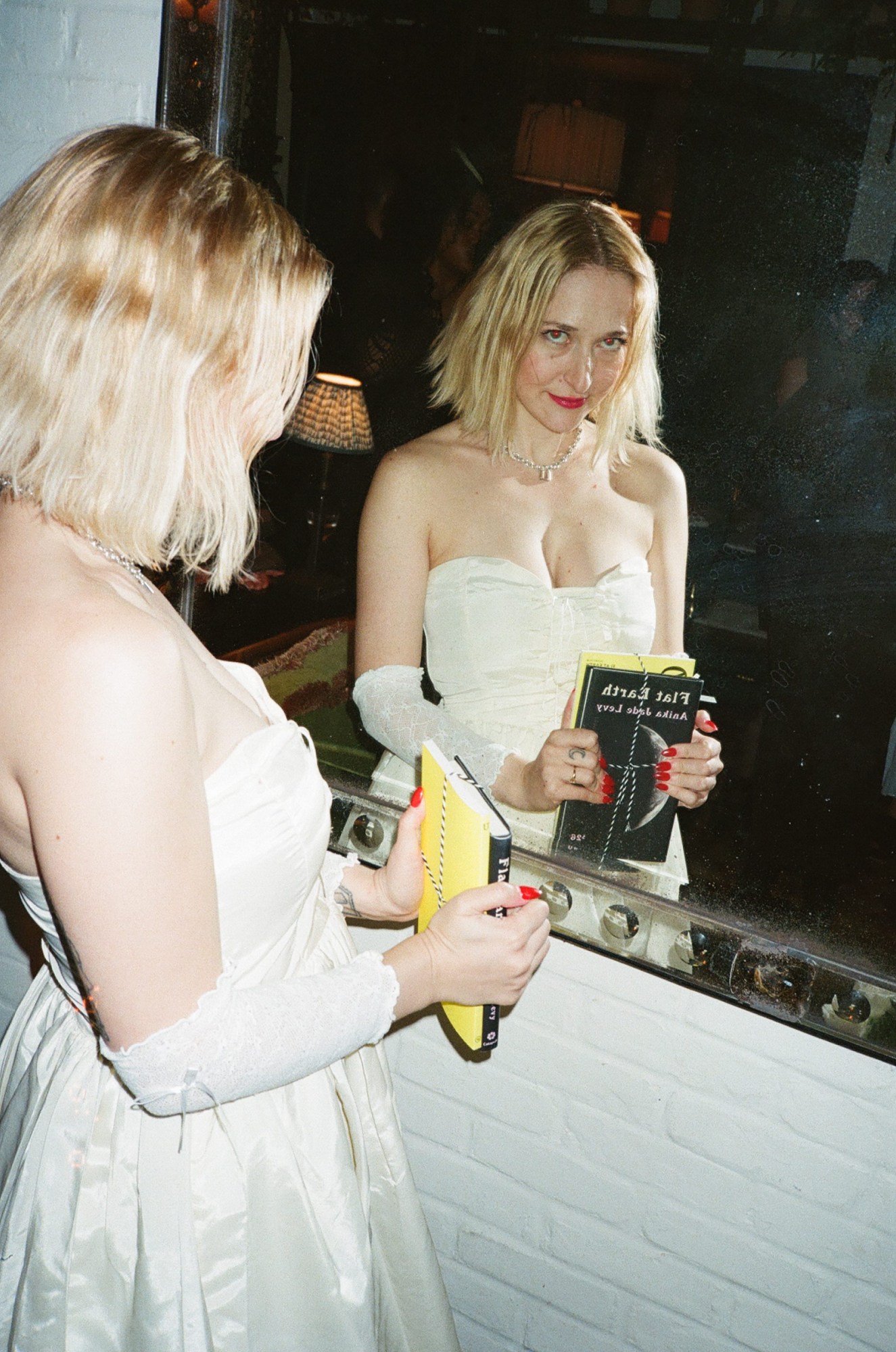

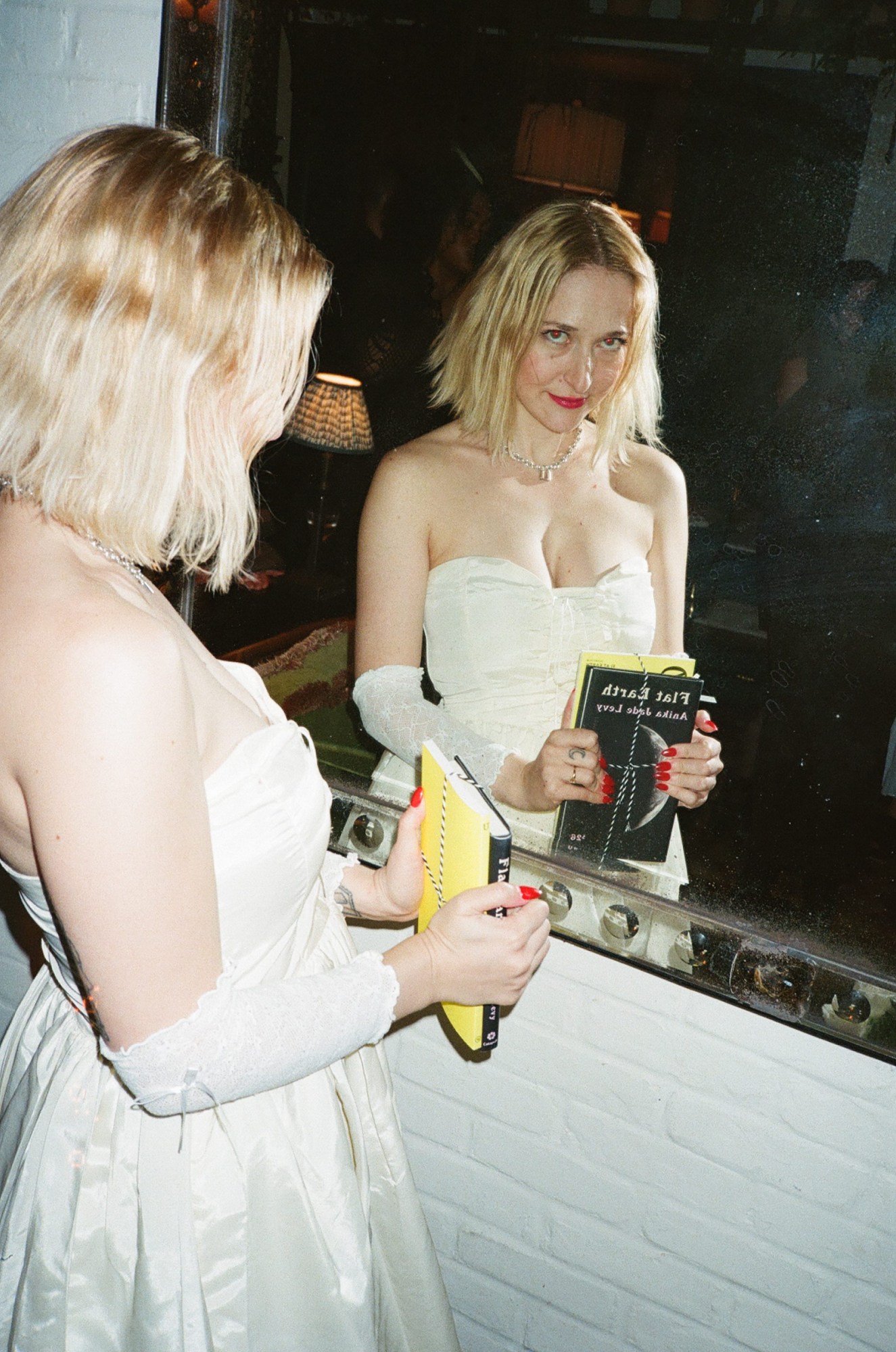

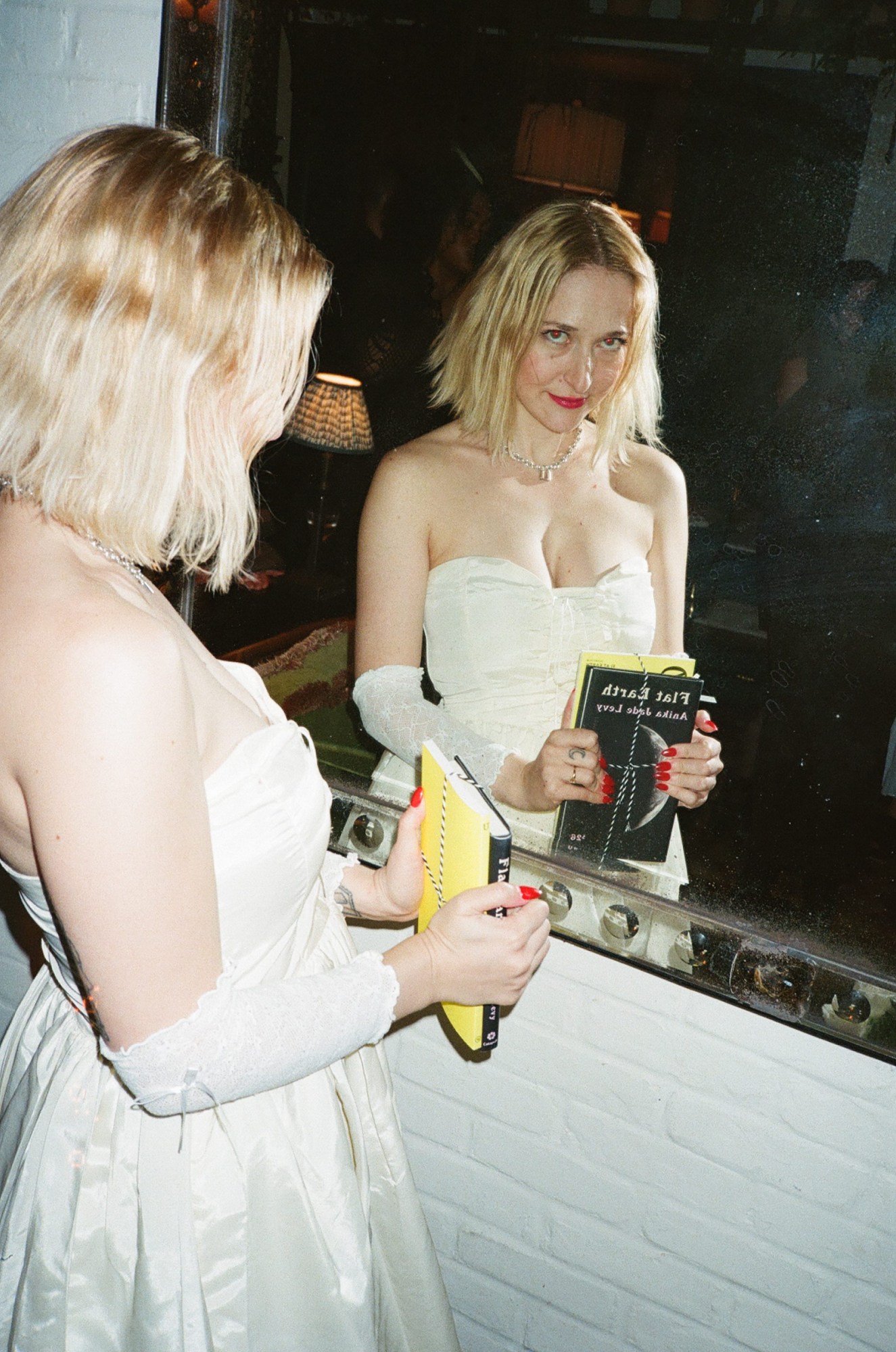

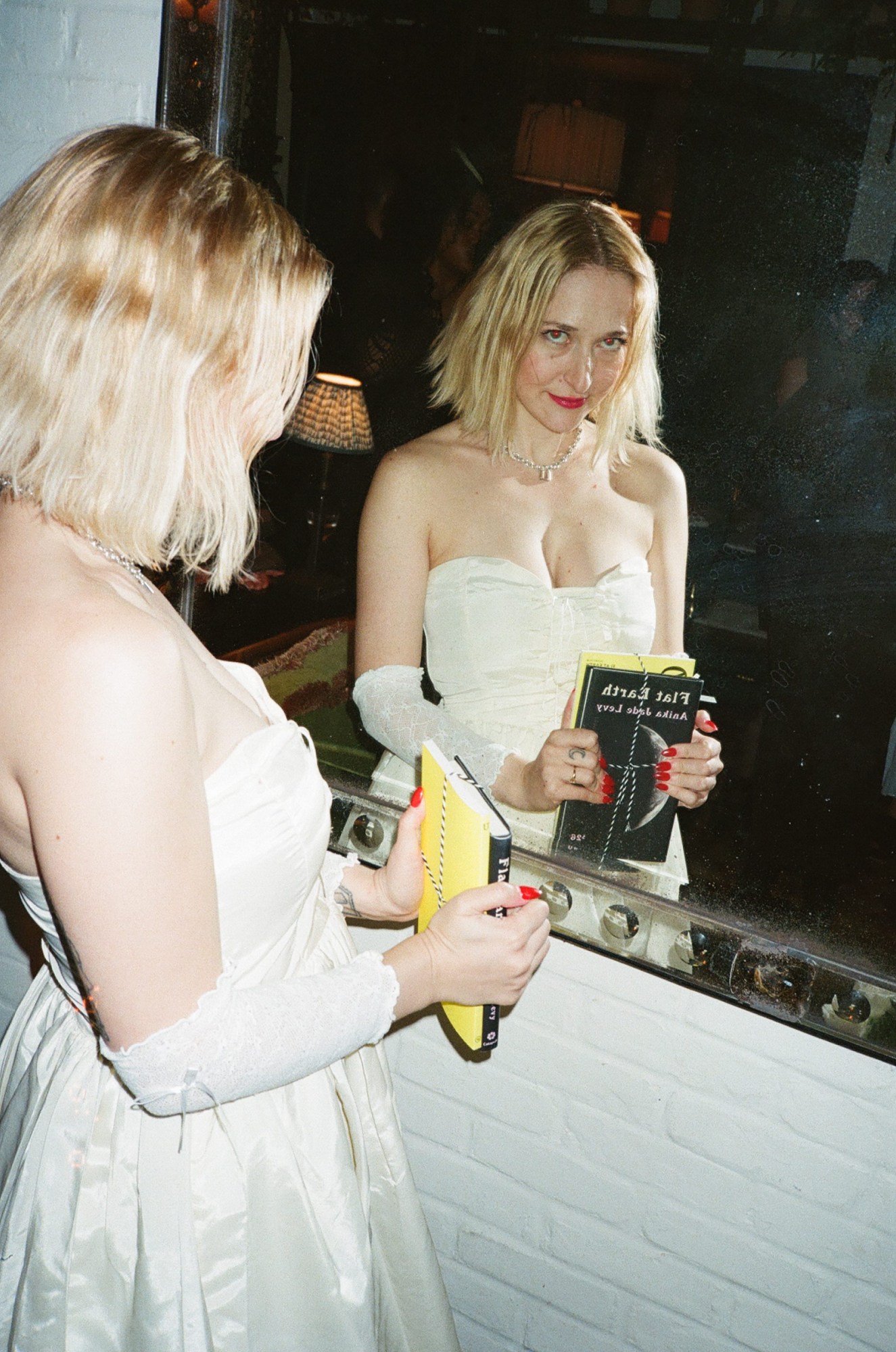

It’s a particularly interesting concept for Levy to explore because friendship is part of her greater artistic project. I first interviewed Levy, along with Madeline Cash and Nat Ruiz in the winter of 2023 for a profile of Forever Magazine about how the magazine wasn’t just the lifeblood of an emerging literary scene, but ultimately a project about friendship. A few days before this interview, I knocked on the door to Levy’s room at the Chelsea Hotel to snap Polaroids before the Flat Earth release party. (Hosted by the literary magazine VOLUME 0, it was a true literary It Girl.) The novelist Sophie Kempf answered the door, while the novelist Stephanie Wambugu was sitting on the bed; they were all sipping Champagne and sharing makeup.

Levy is a writer determined to hold onto the porousness that acts as a sieve for all that is holy despite the spiritual bankruptcy that defines our modern era. “We have nothing to lose because we have nothing,” Levy told me in 2023. In Flat Earth, she accesses the freedom that comes from surrender. On the day of her book release, I spoke with Levy about complex friendships, poverty and decadence, and modern urban malaise.

Sophia June: On the first page of the book, all the pharmacies run out of Adderall. You wrote about this shortage before it actually happened. Did you manifest this or…?

Anika Jade Levy: I do think that the things that we write have some degree of influence over our reality. I also think I was patterning something, observing that it was really over-prescribed. I think when you’re writing, ideally you feel like you are connected to some kind of source. You just have to be careful what you write because then you might not be able to get your prescriptions a year later.

Can you talk about Flat Earth on a sentence level? It’s so attentive and sparse.

I’m much more concerned with success on a line level than with success on a novel level. The grammar and syntax of the book were more important to me than anything else. A lot of that was the way that editing Forever made me keenly aware of how easy it was to lose a reader. It’s my job to carry you from one sentence to the next, which is why the book is so desperate to be liked. I am conscious of the fact that your phone is a foot from you when you’re reading.

I remember chatting with you in the bathroom at a gala for The Drift a couple years ago and you had written around 40,000 words. Tell me about the process of writing Flat Earth.

I wrote early scenes in 2021 and then I took an online class with Sheila Heti and she gave us this prompt, which was to write the scene before the first scene. That’s where the metafictional component of the reports that proceed every chapter came from. I wrote that page in her class and it’s basically the only thing I didn’t change. From there, it was pretty intuitive. When I think about the successes and the limitations of the novel, I feel like I wrote the only book I knew how to write.

Being porous is a crucial 26-year-old experience. How does one remain porous?

You see a lot of really glamorous, intelligent women move into their 30s and develop this armor or hardened quality that’s totally appealing, totally sexy, totally experienced, and worldly. But for me, I worry I wouldn’t have anything to write. I’ve had to really nurture that instinct and fight to preserve it. Ideally it’s something you can take on and off when you leave the house. But for me, at least with this book, it was so much just about being in the world. I think the experience of living in New York or possibly even just living in America or on planet Earth right now is about cultivating a kind of armor. But I think for me at least it’s really important to try to stay penetrable.

So much of being a woman for me has been hiding how much I care about something. But in order to write a novel, you have to care about something so much, even if it’s just caring about women who are cultivating a kind of apathy.

And I actually really do care about those women. I think part of what I was dealing with also was when I moved back to the city and I started working on Forever with my friend Madeline Cash was that it was the first time I had any kind of social capital whatsoever. I’d been kind of a friendless loser all throughout school. I didn’t know how to handle having even underground credibility. Madeline and other people would point out to me that I was really not kind to women. I think a lot of that came from presuming that they wouldn’t be interested in me and being self-protective. Looking at that and examining it was a lot of where the book came from. I think in the same way that romantic love can feel really push pull, I think female friendship can also have that weird erotic push pull.

In the kind of artistic scene that you’re talking about, it’s really hard to form friendships that don’t just feel transactional or shallow.

We all need so much from one another, right? So it’s like, how do you get around that without feeling transactional? Publishing is like academia where the stakes feel so high because there’s so little at stake ultimately. Even when people say, “Oh, this person got a book deal they didn’t deserve,” it’s like, so they got $200,000 for something they worked on for four years? There’s so little at stake and there’s also so much scarcity that it can really feel like a zero sum game. But I also think that increasingly every sector of American life feels that way.

Flat Earth critiques a specific artistic scene that occurred in New York in 2021-2023. How did you approach note taking in your life for the elements that were more reflective of reality?

I was literally just taking notes. That was something that I picked up writing poetry, where I would take notes in long blocks with em dashes separating things. I wasn’t trying to write stuff down like, oh, this is for my project, this isn’t, because in some ways you really can’t know what is going to serve you at all.

When I interviewed you about Forever, you said the magazine was “Wanting to be really wide-eyed, but also embracing the utter cultural, institutional, and material decay.” That’s very much how Avery sees the world. Is there freedom in that?

Something I realized only in the last few months since I’ve been publicizing the book, is that Avery is not nearly as disenfranchised as she thinks she is. She’s at an elite institution and no one is stopping her from being the Susan Sontag of looking at her phone a lot. Even though she has less money than her friends, she has the same level of access that any of her friends have to cultural spaces. Much of this book was about trying to make sense of the coexistence of poverty and decadence. In New York City, that’s something you have to reckon with every single day. It’s like a person literally stepping over a homeless person to get to a Louboutin activation. I think something that people who have precarious finances experience all the time is when you’re like, “I don’t know how I’m going to make rent, but I’m eating in cool restaurants and I’m in New York.”

I do appreciate that Avery is actually broke and not the kind of broke where she could ask her parents for $500. It creates an interesting need for her to do sex work.

The point I was trying to make is that there’s not a single person in our generation who has not experienced some nuance of sex work regardless of their socioeconomic background, whether that was for a night or a dinner, because everything is so hyper transactional. I hear my students talking about paying with their face cards and I’m like, don’t pay with that! Just pay with money! Like, just get a credit card. I think it’s slightly more pronounced in peak Gen Z where everything is hyper transactional. But the sex work is in the water. No one’s avoiding it. Avery is just feeling the most demoralized and affected because she doesn’t have any armor.