When Anthony Hernandez was in his last year in high school, a friend gave him a beginner’s photography book, for no reason other that he suspected Hernandez might make something of it (he was really, really right). Hernandez enrolled at East LA College in 1965 to study photography, and after being drafted for Vietnam service, made his first pictures in a place he felt most at home: downtown Los Angeles. A short walk over the river from Boyle Heights (where Hernandez grew up in the Aliso Village public housing project) downtown L.A. contained seas of highly concentrated street scenes. Hernandez appreciated the city’s harshness — “cities in general can be very hard places with hard surfaces and hard light. That’s what I was interested in,” he tells me on the phone. But because of his innate familiarity, he moved through downtown L.A. fluidly while shooting, “like a street dance.”

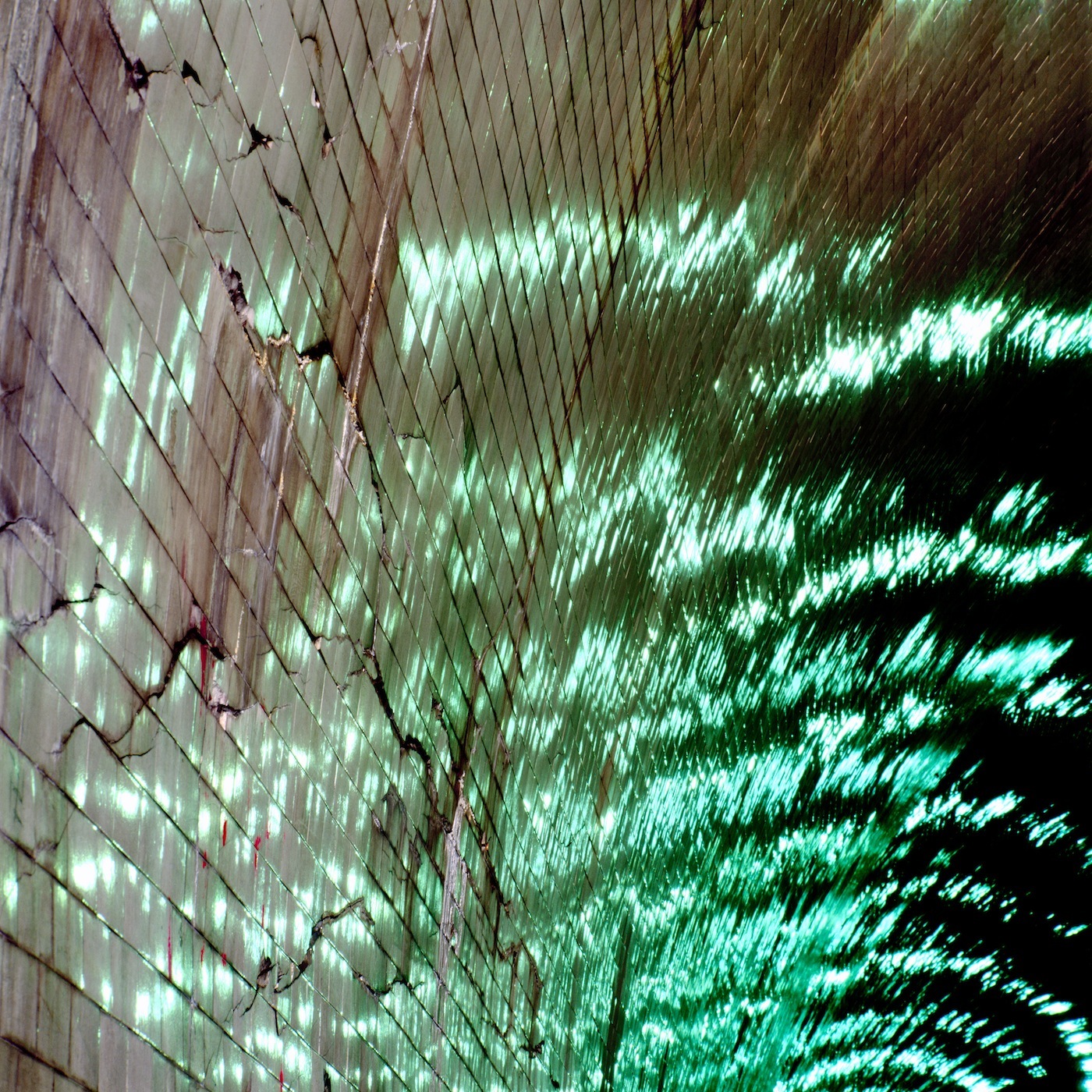

Though Hernandez’s earliest photographs emerged from an exploration of the place he knew the best, his nearly 50-year career has been shaped by anything but comfortable decisions. Hernandez is constantly exploring new forms and subject matters: he’s transitioned from black-and-white to full color, from quick-fire 35mm to methodological large format film, from street scenes to landscapes and abstract details. After making a series of black-and-white photographs of commuters at L.A. bus stops, Hernandez began a new project in 1983 — portraits of shoppers on ritzy Rodeo Drive. He considered that series successful in exploring Reagan-era notions of luxury and consumerism. It was the last time humans have appeared in his images; evidence of their existence and its sociopolitical impact has instead become a focus. Landscapes for the Homeless is a series of homeless people’s makeshift encampments; Everything collects L.A. River detritus. People might not be in his images anymore, but they are never too far out of frame.

Such a wide-spanning body of work is what makes Hernandez’s new show at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and its accompanying monograph, so exciting. Collecting over 160 photographs beginning in the late 60s, the exhibition is Hernandez’s first career retrospective.

Let’s start by talking about this retrospective’s genesis. How did it come about?

I feel really happy this retrospective is happening here at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, because I’ve had this long engagement with Sandra Phillips [SFMOMA’s longtime curator of photography] who just stepped down. They have more of my work than any other museum, and that started with Sandra buying work back in the 80s. About six years ago, I was here for a show that I was included in. I had a meeting with her and Erin O’Toole [associate curator of photography], and they explained that Erin had the idea to approach me about doing a retrospective, and wanted to know how I felt about that. I thought it sounded great. Erin is originally from L.A., and when she started seeing my pictures, they really resonated with her about describing the city. She wrote an [introductory] text to the book coinciding with the show; even people who may think they know me will get a better idea of the work after reading it.

You have such a varied body of work, and it’s developed over many years. How did you arrive at which photographs to include in the exhibition, and in the book?

We approached the idea of a retrospective by really showing and surveying these different bodies of work — making selections to represent them. We started with a selection of the earliest black-and-white pictures and began working chronologically up to the present. That selection was difficult, because there are a lot of different kinds of pictures within that black and white era — 35 mm, 5×7, the the bus stop pictures of the late 80s. From there, we approached things in terms of design and flow. Those bus stop pictures, for example, are a mix of vintage prints I made myself when I made the work, and things that have been newly reprinted using inkjets. Making some of these images larger opened up the picture in a different way — it’s re-representation, re-interpretation.

You’ve spoken about beginning your career without much knowledge of street photography’s history, but with very intimate knowledge of your setting: downtown Los Angeles. Can you tell me about those early experiences?

I was born not very far from downtown L.A.; you could walk there from Boyle Heights, it was just across the river. Downtown LA was a place I really knew, we just loved to hang out in the streets, in the theaters, and explore as kids. Because it’s where I grew up and where I knew so well, it was the first place I really thought about making pictures. And that’s how it began. I didn’t have any prior knowledge of this great tradition or history of street photography — people like Robert Frank or Cartier-Bresson, Paul Strand, anybody. It was nothing to do with that, just with my own experience in the city. It was very pure.

Looking straight on when you’re walking down the street with your camera in your hand, it lends itself to a very fluid way of working — you’re photographing as you’re moving through this crowd of people, you’re capturing these quiet, intimate moments. These kinds of concentrated street scenes can be very challenging; it’s like a street dance, moving through that space. I wanted to make other street scenes, and I did; I traveled to New Orleans, Washington DC, Madrid, Waikiki. I wanted to photograph more, but I realized I couldn’t do that and push myself further with these other cities because I just didn’t have the money to travel. So I started looking at other things in LA — and that’s how the work has evolved.

How has your relationship to LA evolved over your career?

My wife and I left LA in 1991 to go to live in Idaho to live for 10 months before we came back at all — that started this experience of coming back and forth. And what happens when you leave and come back: LA is always fresh, it’s an exciting feeling to come back. I don’t think the work would have been the same if I never left — it may not have been as interesting. It helped to leave; it’s always a fresh way of looking at the city.

I’m suspecting that for many people, this retrospective will be their first exposure to your work. What do you hope they take from it?

My hope is that somebody who isn’t familiar with my work and sees that show is taken with it in a way that they want to bring someone else to share it with them.

‘Anthony Hernandez’ is on view from September 24, 2016 – January 1, 2017. More information here.

Credits

Text Emily Manning

Photography Anthony Hernandez