We’re in a moment when the work of black artists feels like it has unprecedented visibility. Phrases like “gold rush” and “mad scramble” have been used to describe the fervour private collectors and institutions have had for acquiring pieces by legends like Jean-Michel Basquiat and living artists like Kerry James Marshall.

But long before black artists fetched more than $100 million at an auction or were picked to represent the US in the Venice Biennale, there were black patrons, collectors, curators and critics supporting their work. Chef Leah Chase used the walls of her historic Dooky Chase restaurant in New Orleans to showcase greats like Jacob Lawrence, while queer critic and curator Alain Locke — the “Dean of the Harlem Renaissance” — organised an unprecedented show of black art in 1940 that drew huge crowds and featured work by pioneers like Charles White, to name just two.

Today, collector and patron Bernard Lumpkin and curator and critic Antwaun Sargent are standard bearers of this tradition. They’re both committed to championing black creators even after the fickle, white-ruled art market loses interest and moves on to something new.

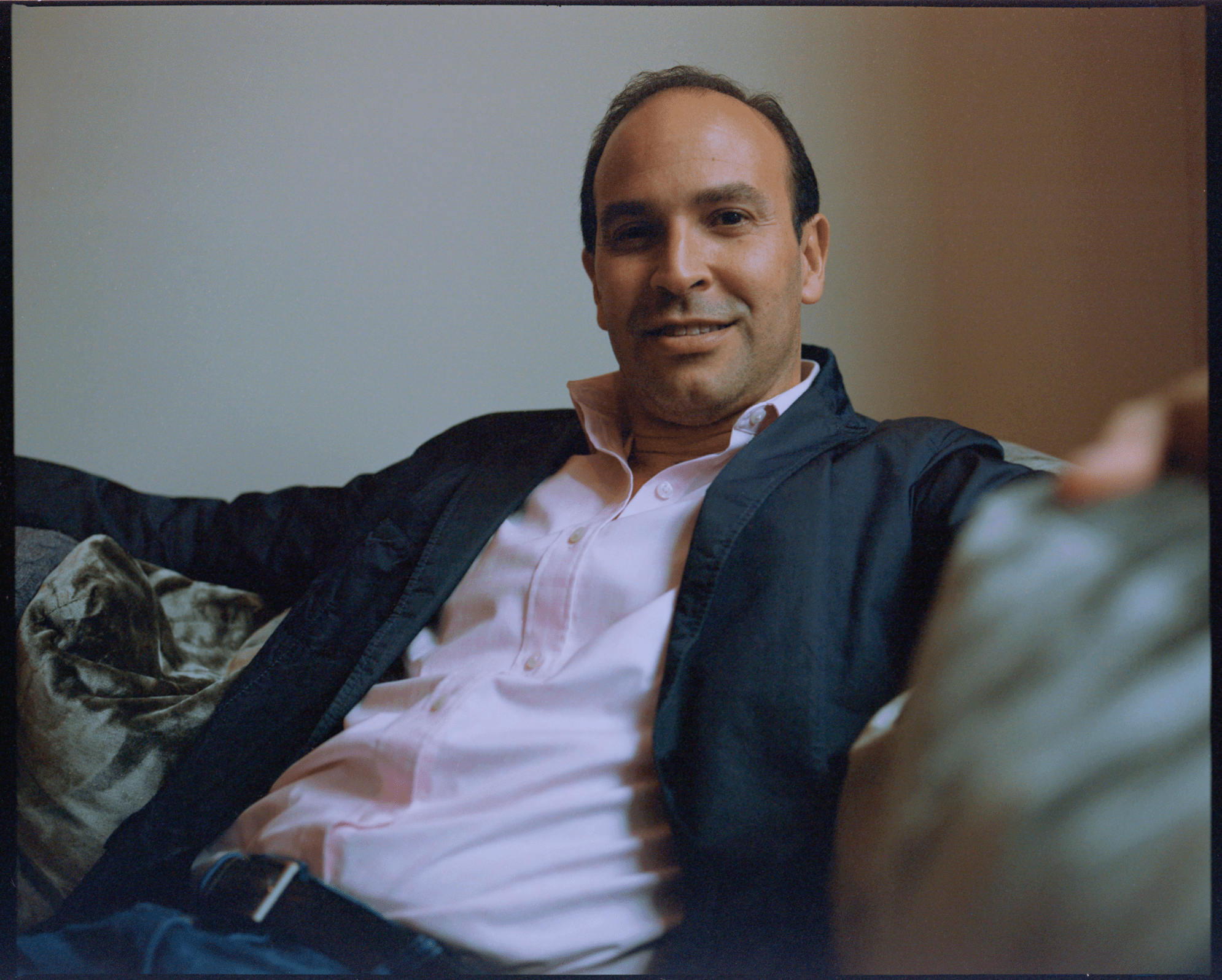

For the past decade, Bernard has acquired nearly 500 works of art, many of which were made by artists of colour at the outset of their careers. But the 50-year-old is more than just a collector, he also helps black artists get into major institutions as a member of the Whitney Museum of American Art’s Education committee and Painting & Sculpture committee. He’s also a trustee at The Studio Museum in Harlem.

Antwaun has played a similar role as a critic. Through countless articles for publications like VICE, The New Yorker and The New York Times, he’s celebrated and interrogated the work of everyone from Awol Erizku to Barkley L. Hendricks. The 31-year-old’s lauded 2019 book with the Aperture Foundation, The New Black Vanguard, focuses on the work of 16 young commercial black photographers from across the diaspora who are exploring their identity through fashion and making incredible art while they’re at it.

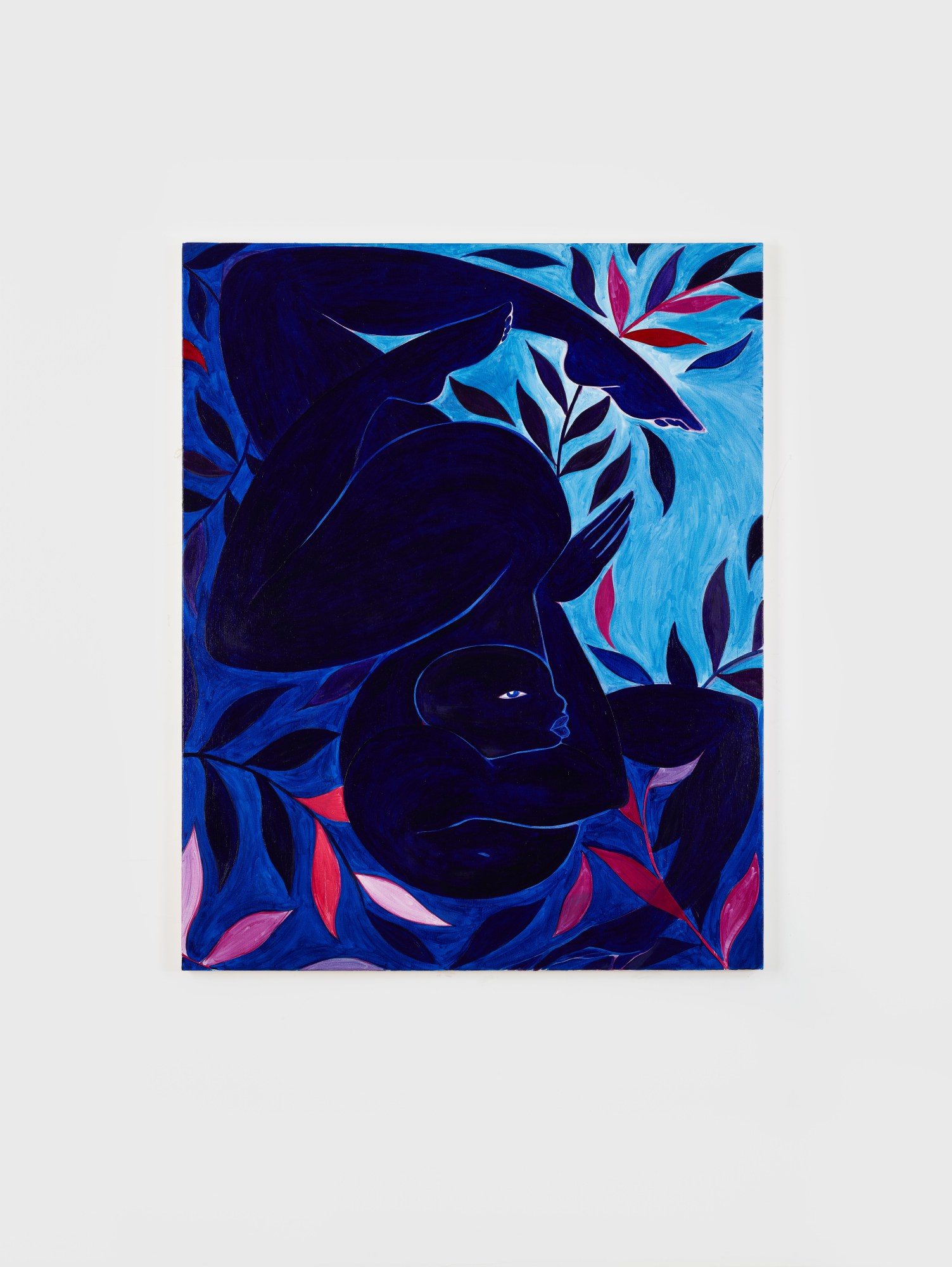

Most recently, Bernard and Antwaun have joined forces with Young, Gifted and Black, an exhibition showing at Lehman College in the Bronx until 6 May. The show features more than 50 works of art across various mediums that were made within the last two decades, selected by Antwaun and the artist Matt Wycoff from the vaunted family collection amassed by Bernard and his lawyer husband Carmine D. Boccuzzi. With early works by renowned artists like Kara Walker and Mickalene Thomas presented alongside more recent creations from emerging artists like Sable Elyse Smith and Arcmanoro Niles, the show creates a dialogue with itself. Taken together, one gets a survey of the ways in which two subsequent generations of black artists are exploring everything from language and social abstraction to landscapes and the colour black.

Earlier this month, Antwaun and Bernard got together in New York City at the latter’s elegant Tribeca apartment to talk about their collaboration on the new exhibit, which will be travelling across the rest of the US throughout 2020 and has spawned a hardcover artbook, out in July. Sitting among a towering and touching portrait by Henry Taylor of a young black man ready to dine on a piece of chocolate cake, a spectral resin sculpture by Kevin Beasley, and some colourful drawings by Bernard’s kids, the patron and the critic discussed their journeys to the centre of the black art world and their mission to support and preserve black art long after the hype dies down.

Antwaun Sargent: The first time I had an out of body experience with art was when I encountered Kara Walker’s work in a theory course at Georgetown University during my sophomore year. It made me cry, because I hadn’t faced a view of American history like hers before. I became interested in this truth teller, someone who used visuals to challenge our notions of culture and power. At the time, I was like, “I need to meet this woman.” And I did eventually meet her and write about her work. So that was an important catalyst for me into the art world. What about you?

Bernard Lumpkin: My dad grew up in Watts, in South Los Angeles. He worked hard to make a life for himself outside of that community as a physicist. But he always maintained ties. So as children, we’d visit. One of the great things about Watts is a sculpture called the Watts Towers, made by Simon Rodia. Seeing those towers were my first clear memory of looking at art. And it wasn’t in a museum or an exclusive part of town. It was down the street from my grandma’s house and there were kids playing around it. This showed me that art can happen anywhere, and even more that art can happen in the context of a broader community.

It’s weird. It took me a long time to call myself an art critic or curator. I had a hard time squaring what I was doing with the racism and misogyny pushed by people who’ve occupied these spaces in the past. Some older critics are praising black art now, but it’s not like Ed Clark or Kerry James Marshall weren’t around in the 70s. There still needs to be a reckoning for the way white critics and curators kept black people out. But I realised if I didn’t call myself a critic, I was erasing my own work. The thing is that institutions are a collection of people. So you’ve got to be willing to engage with those institutions to really change them. I don’t want to be a gate-keeper. I want to make sure the audience is able to see the work.

If there were more black curators, there would be room for more kinds of work by black artists. But there are still too few people doing this work in institutional spaces.

Yeah. I can’t write about every black artist. And you can’t buy every artwork.

We definitely need more people who are patrons to these artists. Being a collector, you buy a work of art and you live with it and enjoy it. But being a patron is a deeper kind of engagement that requires a sort of on-going conversation with the gallery and curators about the work and an ongoing commitment to acquire more work or to support the artist when they have a museum show. It’s bigger than just getting one painting. Patrons sustain the artist.

Before I actually met you, I knew of you because you were doing that kind of work with artists. Your collection is a collection that artists want to be in. The fact that you host talks between artists and dinners for artists out of this apartment is incredible.

We try to act like a museum without being a museum and bring the black art community into our family.

It was at one of your events here that you talked to me about getting involved in the Young, Gifted and Black project. Now it’s a proper exhibition. That to me really highlights the existence of the black art world that supports black art. And the idea that this black art world is there largely to open the gates for more black artists to come through.

The tension lies between the desire for more mainstream acceptance, while retaining the differences that make up the black experience. Does the struggle end when you have black artists showing at the MoMA? Well, yes and no. The struggle becomes something else. Now, there are new struggles.

Sure. The black artist gets into the museum, but the inequality shows up spatially. You rarely see a black retrospective at MoMA. And you generally get black artists in the free, non-admission galleries of major museums. But one of the things I love about the Young, Gifted and Black exhibition is that it has that external conversation about blackness in white spaces (which I’m increasingly less interested in), and it also has an internal conversation about how blacks negotiate their own blackness. For example, when you have work by artists like Jonathan Lyndon Chase and Mickalene Thomas presented together, who are separated by a generation or so, you realise that the ideas of black queerness have evolved. That’s what’s been great about doing this project: I’ve been able to track the changes of black identity through black artwork.

To see the choices that you and Matt Wycoff made was awesome, because it created a dialogue between works of art that weren’t apparent before. Obviously, I live with a lot of these pieces. But to see the work in a new way was exciting and new and fresh. And that’s what great curators and critics like you do.

Working on the book with you, it was amazing for me to see how open you were in telling stories outside of your own. A lot of the book is about your personal collection, but it also feels like a how-to for black people to start collecting art. I love that we were able to share your journey of not being just a collector, but also a patron. And we need more of that. Every POC community should have patrons for its artists.

Young, Gifted and Black, curated by Antwaun Sargent and Matt Wycoff, is on show at Lehman College Art Gallery until 2 May 2020

Credits

Photography Davey Adesida