On a cold and bleary day in 2014, photographer Arlene Gottfried arrived at Daniel Cooney Fine Art in New York swathed in a voluminous coat, casually wheeling a small suitcase behind her. Then in her mid-60s, Gottfried cut a distinct silhouette from the bevy of young photographers bearing pricey leather-bound portfolios that regularly passed through the gallerist’s Chelsea space.

Cooney took the meeting at the recommendation of photographer and filmmaker Paul Moakley, and remembers having no idea what to expect. In front of him was a very small woman, an untamed halo of salt and pepper curls surrounding her cherubic face: at once once unassuming and provocative. “At first I was a little suspicious; I was like, who is this lady that just popped up?” says Cooney, speaking by phone from the gallery.

As Gottfried unzipped her suitcase to reveal a stash of yellow Kodak boxes neatly filled with hand-printed street photographs, Cooney began to relax. “As soon as I saw that, I knew she had something good,” he says. “Once I started looking through them, I kept on going, and thought, wait a minute, what am I missing here? Paul told me she was having trouble exhibiting her work and I thought, no way. But he told me she had never really shown her work [in a commercial art gallery] before.”

In that moment, he made a decision that would change both their lives, giving Gottfried gallery representation during her final years, one that Cooney would continue to build following her death in 2017 from breast cancer. “I accidentally became her best advocate,” he says. “Arlene became a significant figure in my life because she really shifted what my gallery is about. I had been showing young artists in their 20s and 30s, some still in school. Now I’m focused on people that were overlooked, with 40 or 50 years of work behind them.”

After opening his first gallery in Williamsburg in 2003, Cooney moved to Chelsea the following year, just as the neighbourhood was becoming the centre of the downtown art world. While he has always championed the work of underexposed artists, it wasn’t until meeting Gottfried that Cooney shifted his focus from early to late-career artists. Since then, he has devoted himself to elevating the work of groundbreaking artists and photographers like Donna Ferrato, Jill Freedman, Larry Stanton, Steven Arnold and Jimmy DeSana, who are only now beginning to receive their proper dues in the art world.

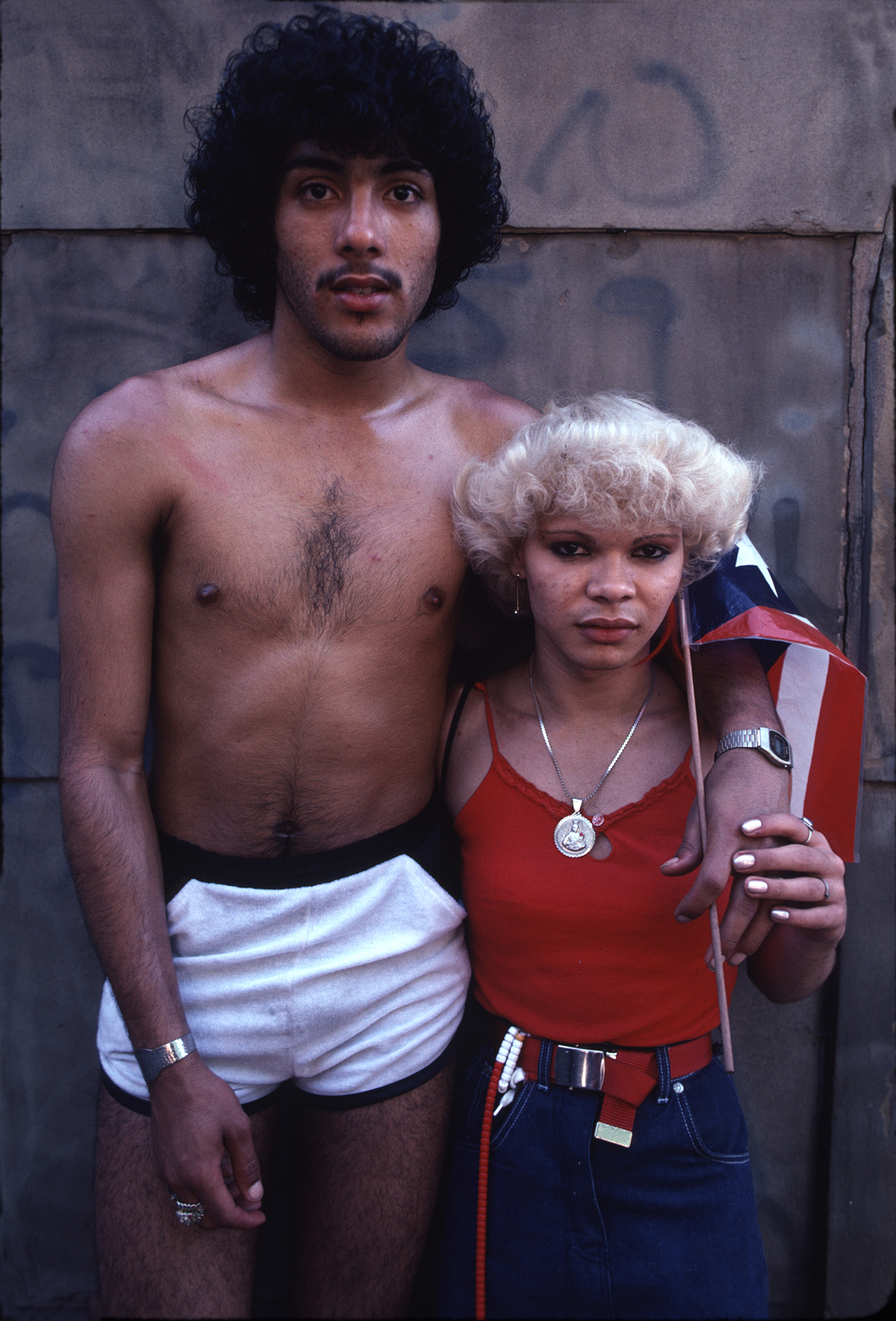

Since meeting Gottfried, Dan has curated five solo exhibitions of her work to critical acclaim, bringing the Brooklyn bon vivant’s life work to the world stage just as the city she chronicled had all but disappeared except in her photographs. Born in Coney Island in 1950, Gottfried was the oldest of three children, her sister Karen and brother, actor and comedian, Gilbert Gottfried — a quiet, shy boy wholly unlike his frenetic on-stage persona. When Gottfried was nine years old, her family moved to Brooklyn’s Crown Heights, a predominantly Black and Puerto Rican neighbourhood home to the legendary Empire Rollerdrome, the birthplace of Roller Disco. (It was a place she would return to as an adult, camera in hand).

“When people were posing for her… I think she got a thrill out of these sweet, special moments”

paul moakley

Coming of age in the 60s, Arlene hit the streets with an old 35mm camera her father gave her, revelling in and documenting the pleasures of street life and community. As the decade gave way to the 70s, she witnessed the city spiral into decay under the Nixon White House policy of “benign neglect”, which systematically denied basic government services to Black and Latino communities across the United States. On the brink of bankruptcy, New York went up in flames as landlords hired arsonists to torch their property for insurance money across the Bronx, Brooklyn and Manhattan.

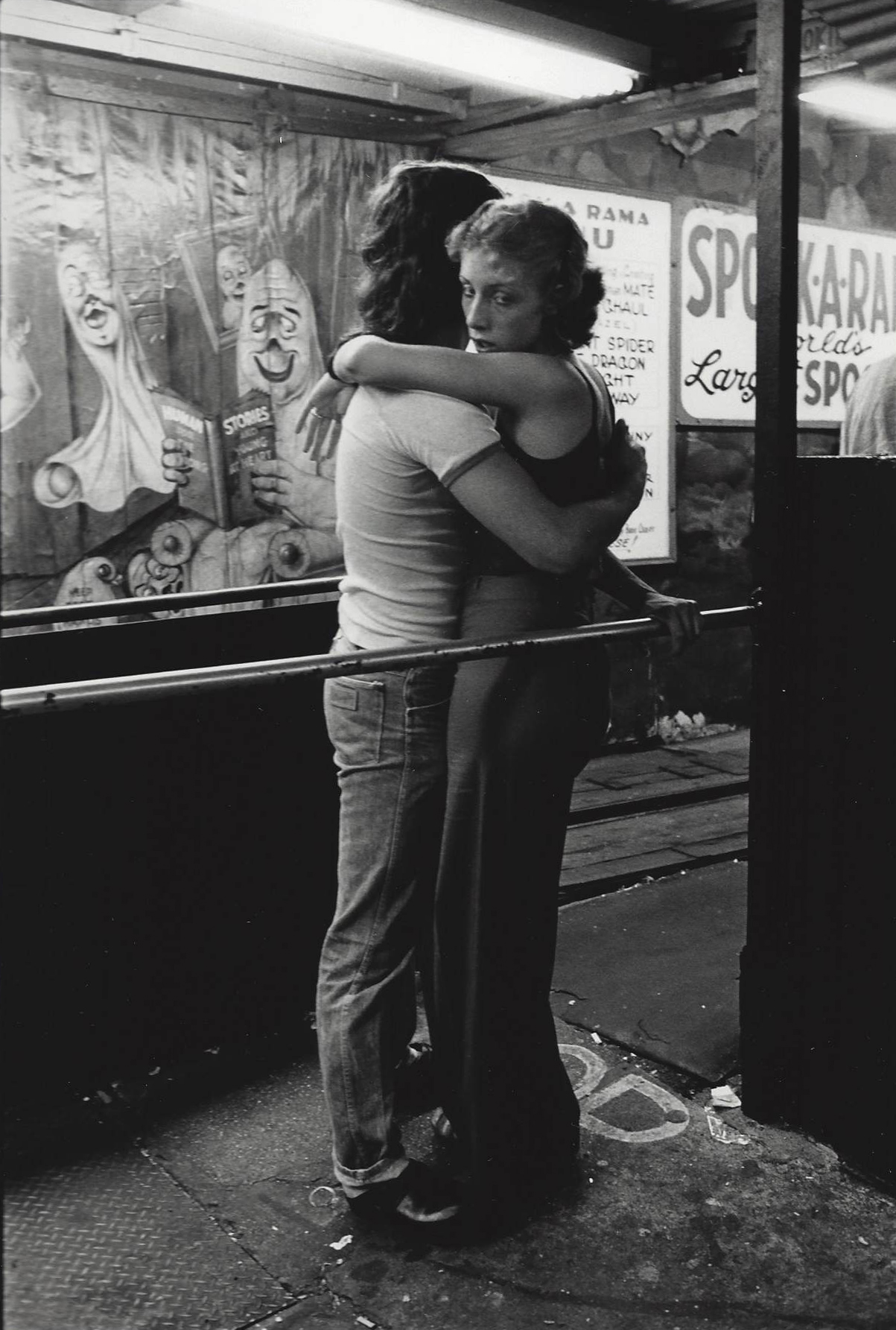

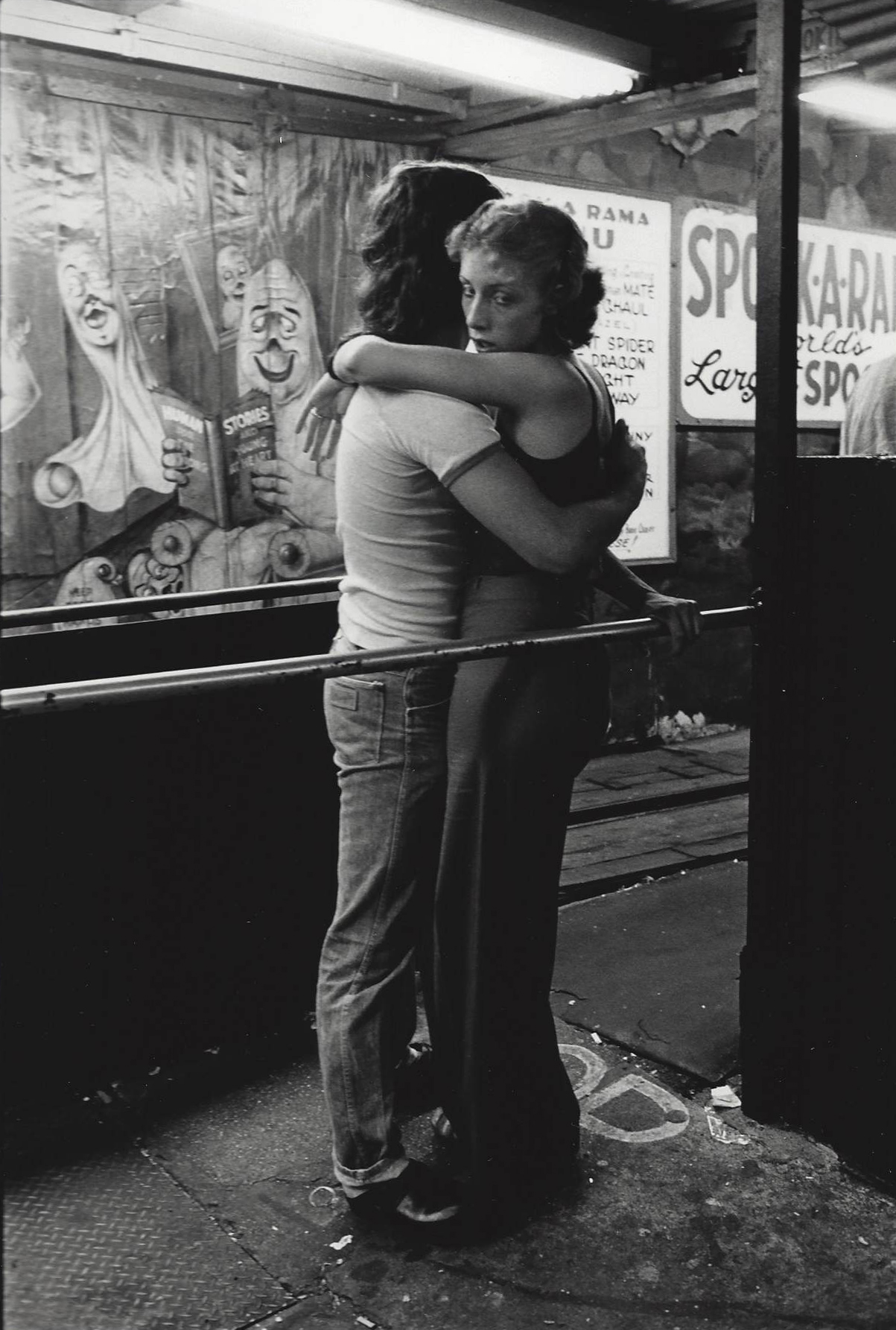

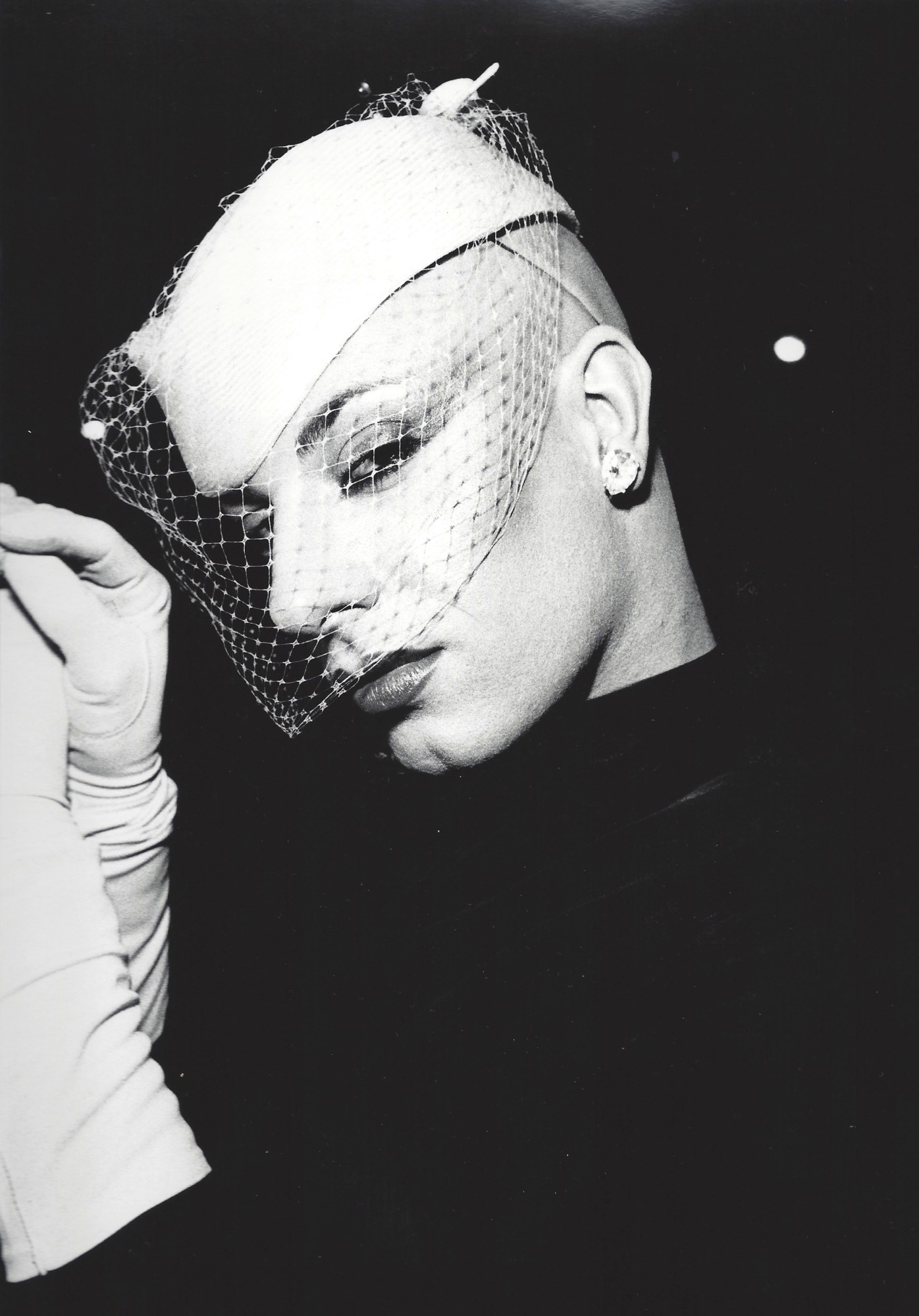

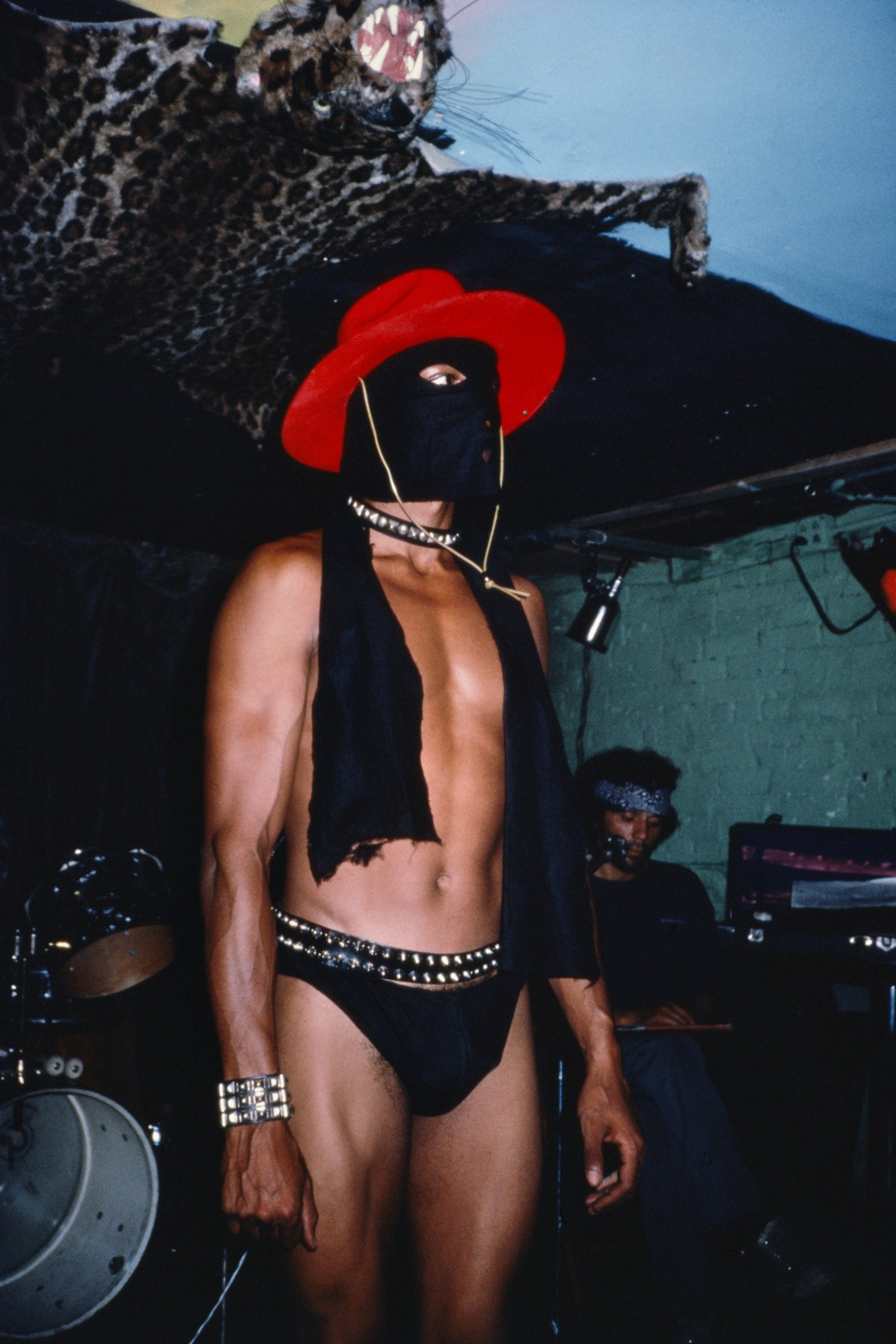

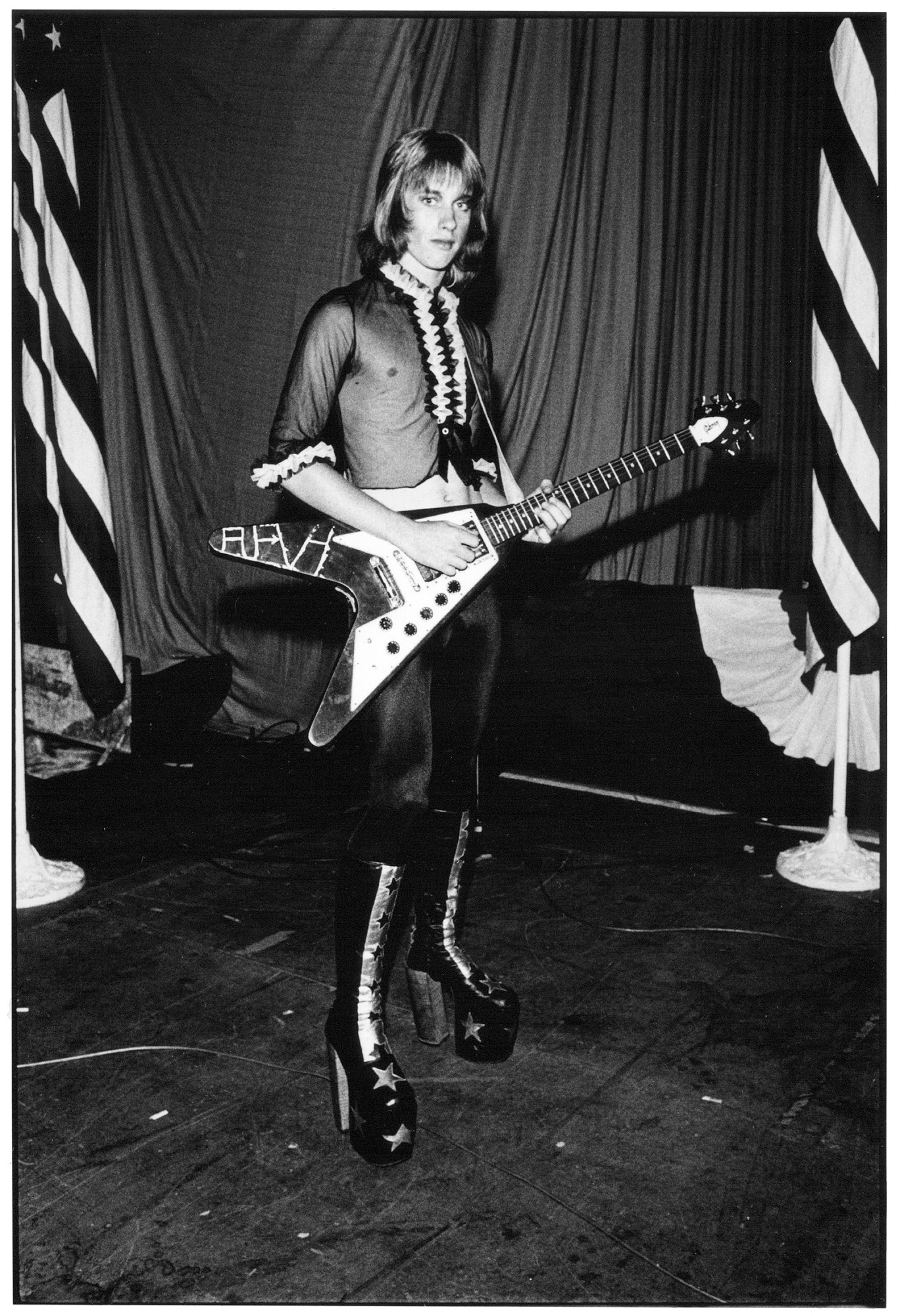

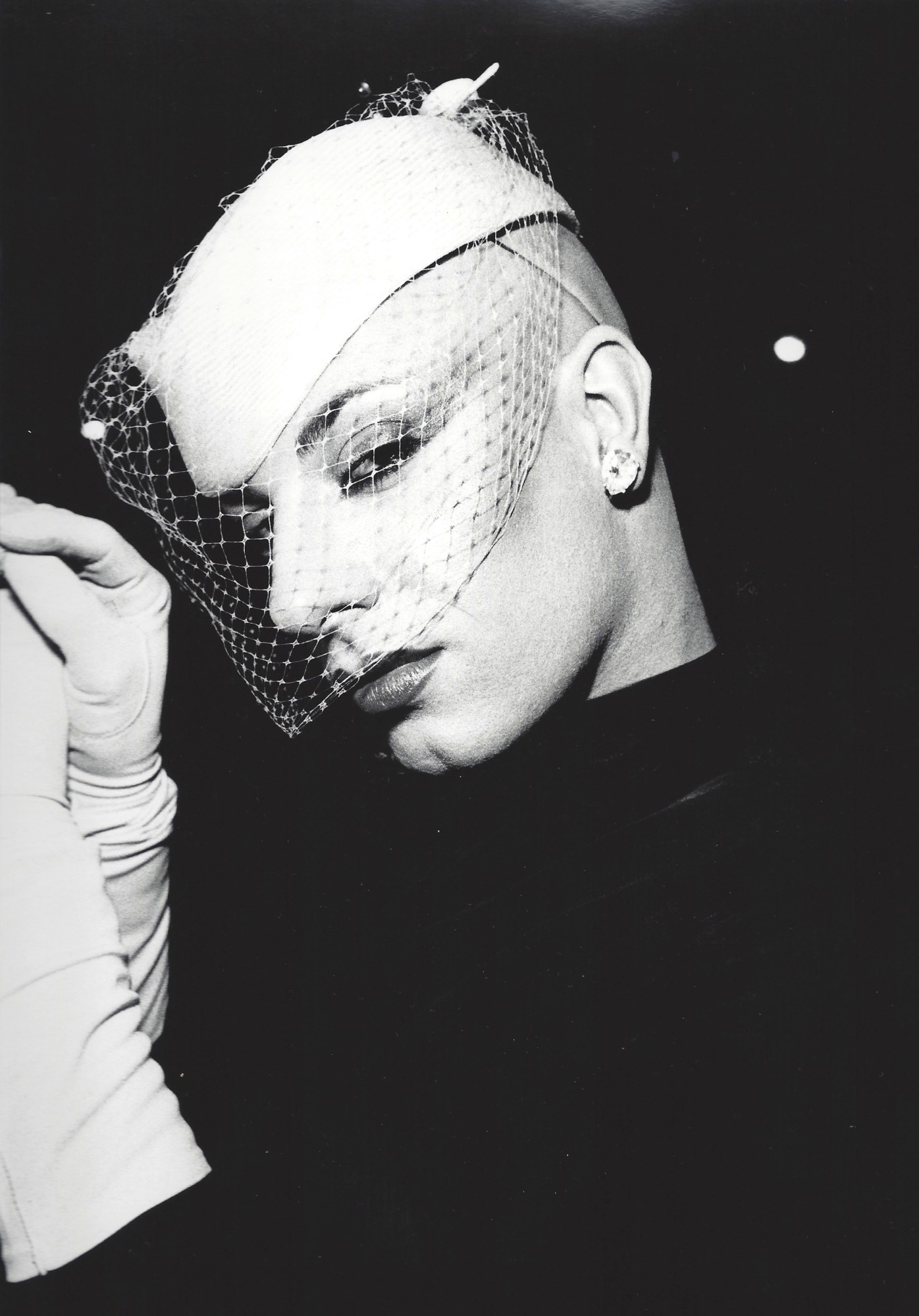

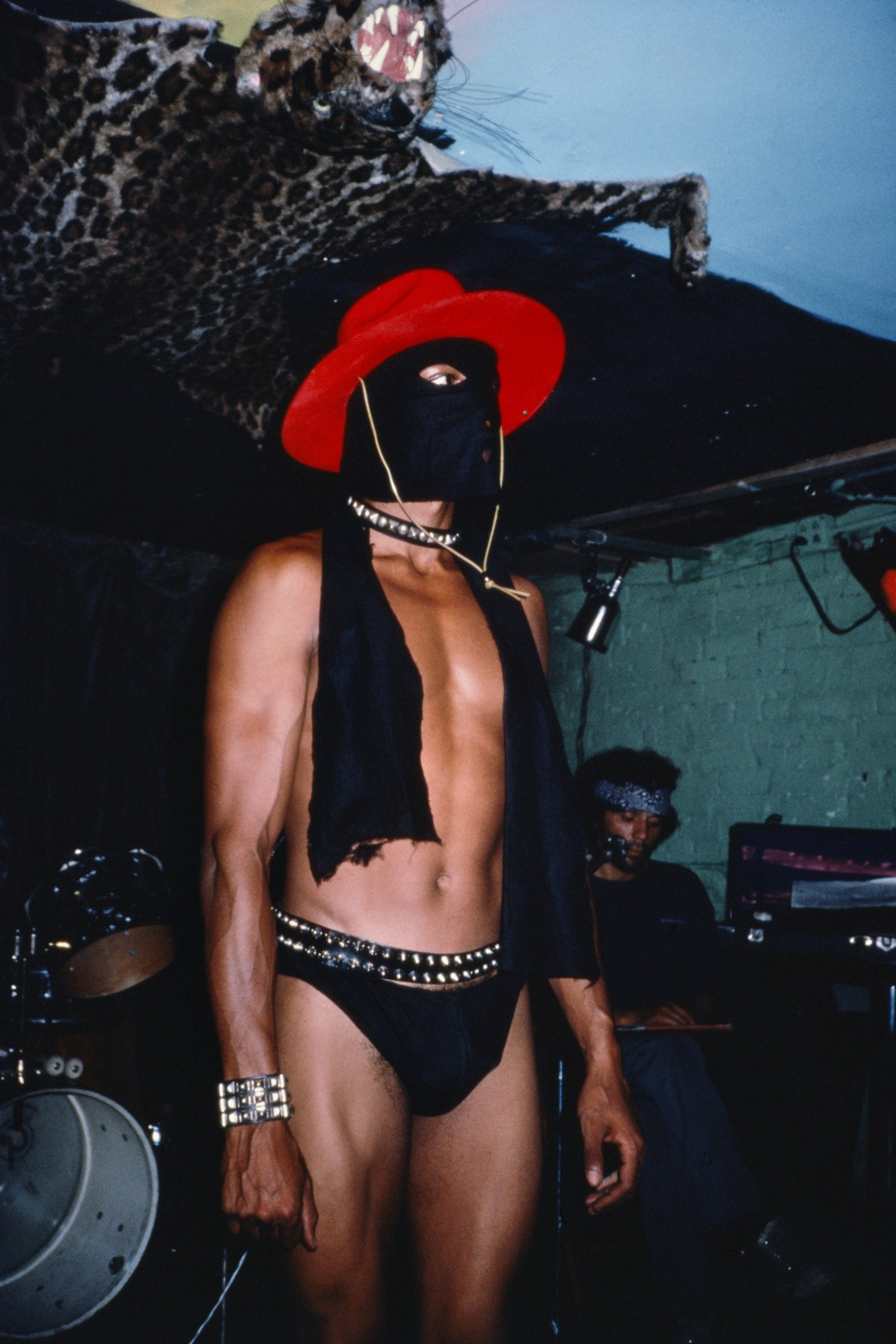

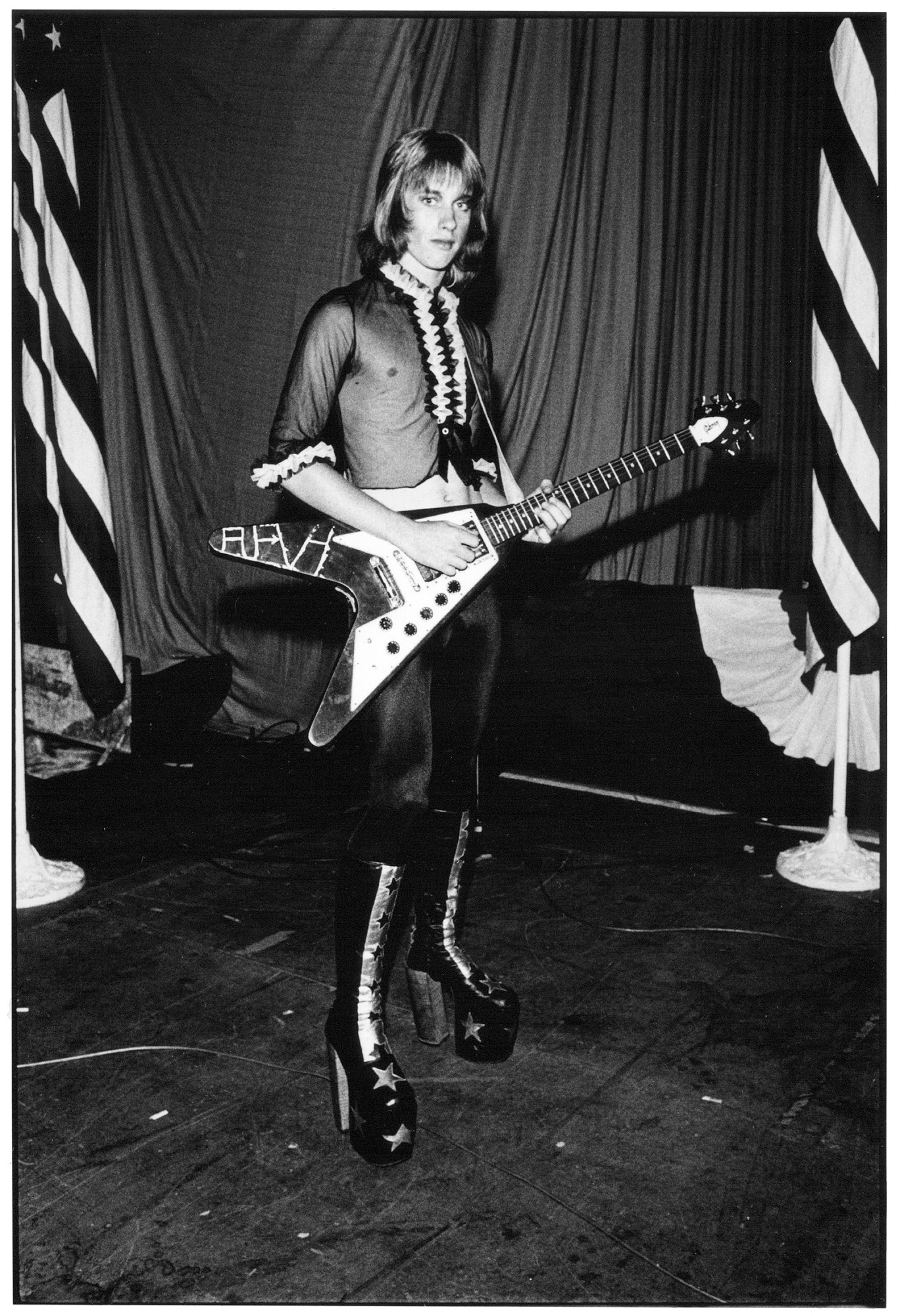

Amidst the rubble and ravages, Gottfried saw beauty, power and strength of the human spirit, all of which became the hallmark of her work. Gottfried chronicled the world in which she lived, crafting an intoxicating portrait of New Yorkers from all walks of life: drawn to the grit and glamour of the city’s performers, artists, activists, addicts, sex workers, street corner legends and regular folks.

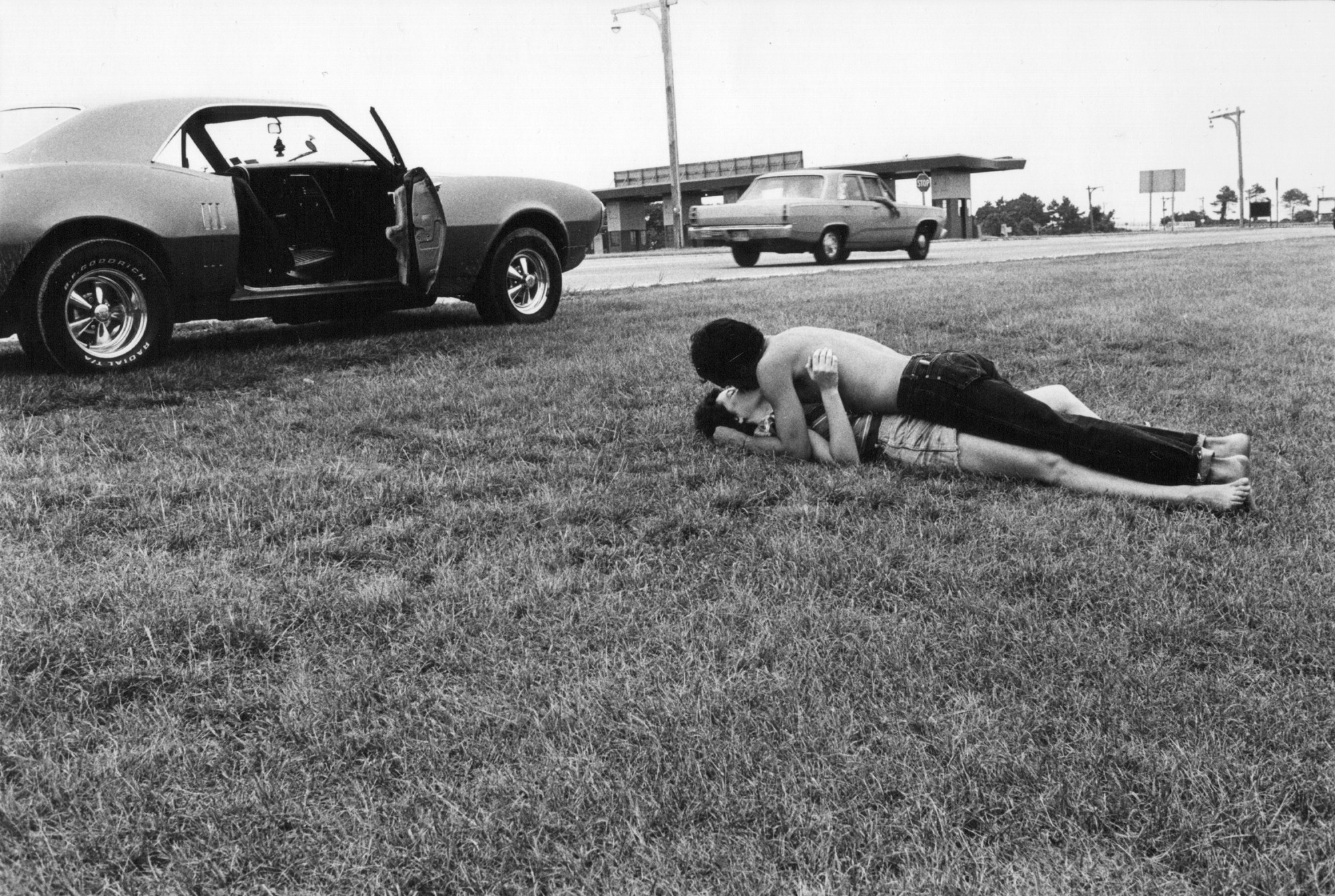

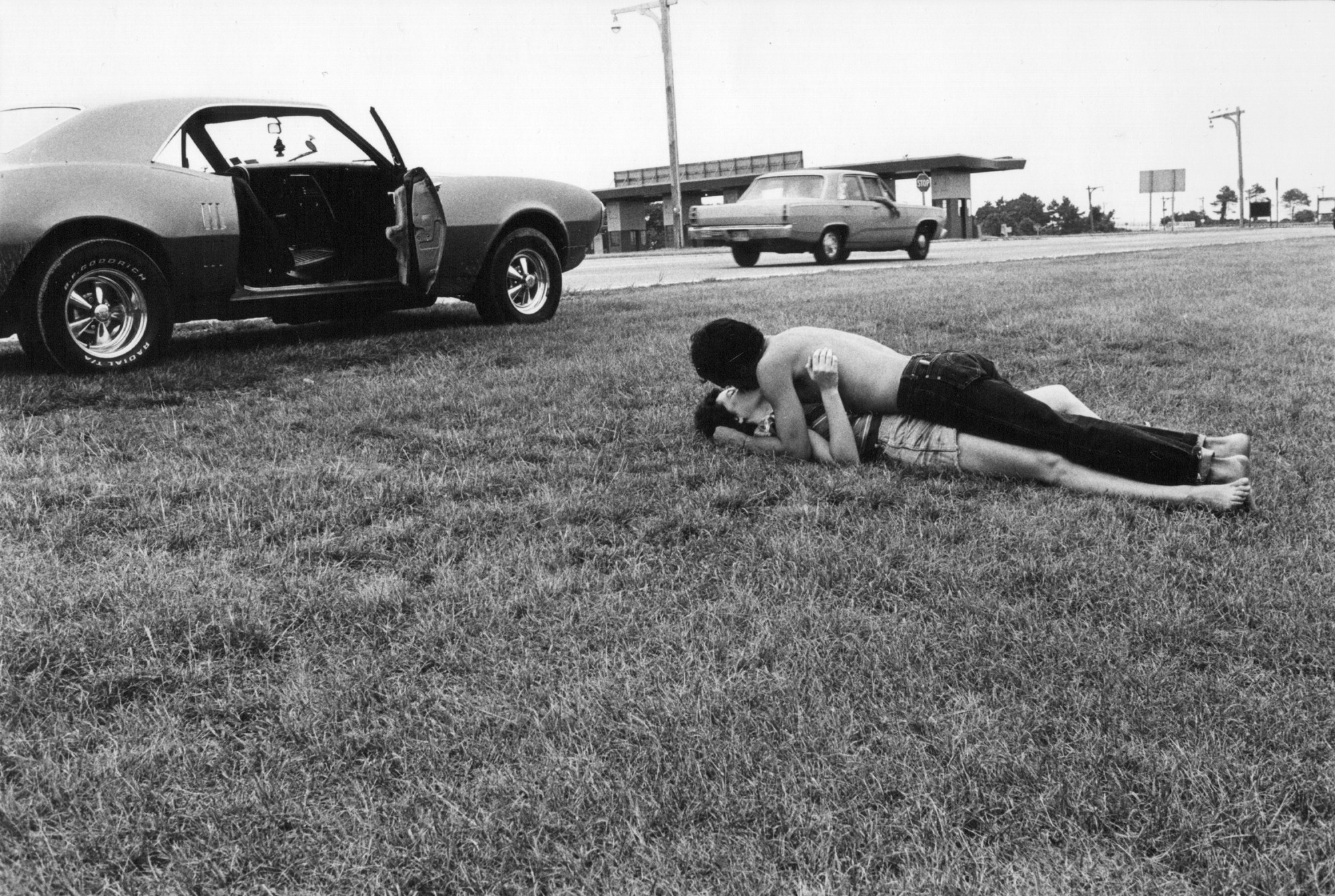

At a time when photography hadn’t yet been recognised by the art world, making pictures was a radical act of faith. She wandered the streets of the city, drawn to the passion and pathos unfolding amidst scenes of everyday life. In “Couple Kissing on the Highway”, she stands just a few feet away from a couple that have parked near a rest stop and thrown open the car door to snog on the grassy side of the road; “Woman on Subway” sees Gottfried capture a normal woman on the subway in a state of deep rumination. More often than not, Gottfried worked collaboratively with the people she encountered. She photographed trans activist Marsha P. Johnson on multiple occasions, each street portrait a collaboration between two visionaries who communed on a shared idea of what was beautiful.

Viewed together, Arlene’s photographs form a map of her life, one that she eventually chose to reveal through her artist books. From 1999 to 2015, Arlene created five monographs, some crafted over decades, that read as a rapturous and intense family photo album. She photographed the church choirs in which she sang gospel for The Eternal Light; crafted an epic portrait of living with schizophrenia in Midnight; captured the DIY heart and soul of New York for Sometimes Overwhelming; celebrated the Puerto Rican Day Parade in Bacalaitos and Fireworks; and completed her journey with Mommie: Three Generations of Women, in honour of her grandmother Minnie, mother Lillian and sister Karen.

Paul Moakley, an executive producer at The New Yorker, played a pivotal role in Arlene’s late career, sending her on assignment to photograph a gospel music producer while at Newsweek, and curating a show of her work at the Alice Austen House Museum in Staten Island. “Arlene’s strongest work is when people are well aware that she is in the room,” he says. “They are looking directly at her, posing for her, having an encounter with her. I think she got a thrill out of these sweet, special moments. She always carried a small camera in her bag and would often dart after a person that caught her eye.”

Moakley still remembers the first time he saw Arlene’s work on the cover of the Fall 1998 issue of DoubleTake. Her blurry red-tinted photograph of a young couple locked in a tender embrace stood apart from other work he had seen as a photography student. “I was very young, and I wanted to know why that was a good picture. I had so many questions,” he remembers. “I had a bit of anxiety about wanting to know the technical side, but also wanting to have the freedom to be creative. When I saw [her] pictures, I instantly knew why they were so special.”

As he leafed through the magazine, Paul realised that Arlene’s photographs from The Eternal Light were not only a document of life in the Black church, but an act of devotion unto itself. In her hands, the camera revealed the presence of spirit making itself felt through light, colour and movement, transforming the photograph into a moment of affinity for the artist whose business card, after all, bore the legend: “The Singing Photographer.”

“Arlene was everywhere with this group of singers, getting these highly cinematic moments that were so sharp with a hard flash and that incredible old Kodachrome colour – but the pictures were also so intimate,” Paul says. “She got so close to them because she was also having a religious experience: connecting to the music and becoming a real part of their world.

“I feel that’s how she approached all of her work,” he continues. “It was personal and there were no boundaries.”

Gottfried lived as an artist, preferring to make art in community than to jockey for position in the art world. Deeply private, she chose not to include text in any of her books, preferring the work to speak for itself. But she made a single exception, at the very end of her life.

“I love telling stories with pictures,” Gottfried wrote in 2015’s Mommie: Three Generations of Women. “When I take photographs, I am drawn to character. I’m drawn to the people of certain places, places like Coney Island, Brighton Beach, the Puerto Rican Day Parade – the endless places to go that you make a day trip out of. Pictures are a part of that experience. I like following my heart. I like meeting people, and I like to travel.” Even if that travel, as she puts it, just means “taking the crosstown bus.”

Credits

Writer: Miss Rosen

Photography: Arlene Gottfried (Courtesy of Daniel Cooney Fine Art, New York)