There is a lifetime of work behind A Lifetime of Wandering, the first posthumous exhibition of Arlene Gottfried’s arresting street photography. Gottfried — who passed away in August due to complications from breast cancer — left an archive spanning four decades and 15,000 prints.

“When Arlene was a kid, her mother always told her not to wander,” explained Daniel Cooney, Gottfried’s gallerist. “She used to say that having a camera gave her a reason to wander, and that it’s been a lifetime of wandering.” Along her way, Gottfried captured the lives of other New Yorkers with vibrancy and care.

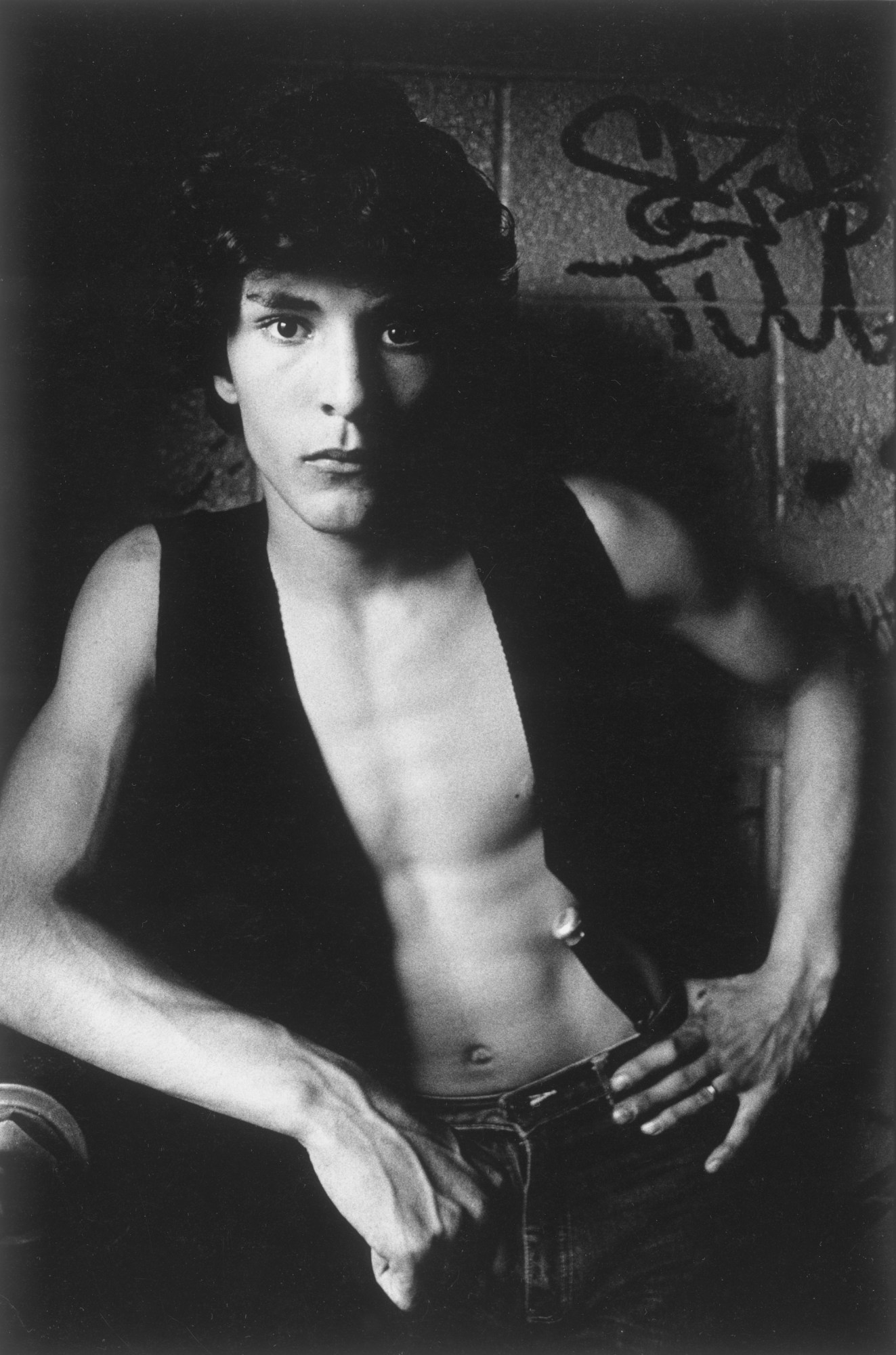

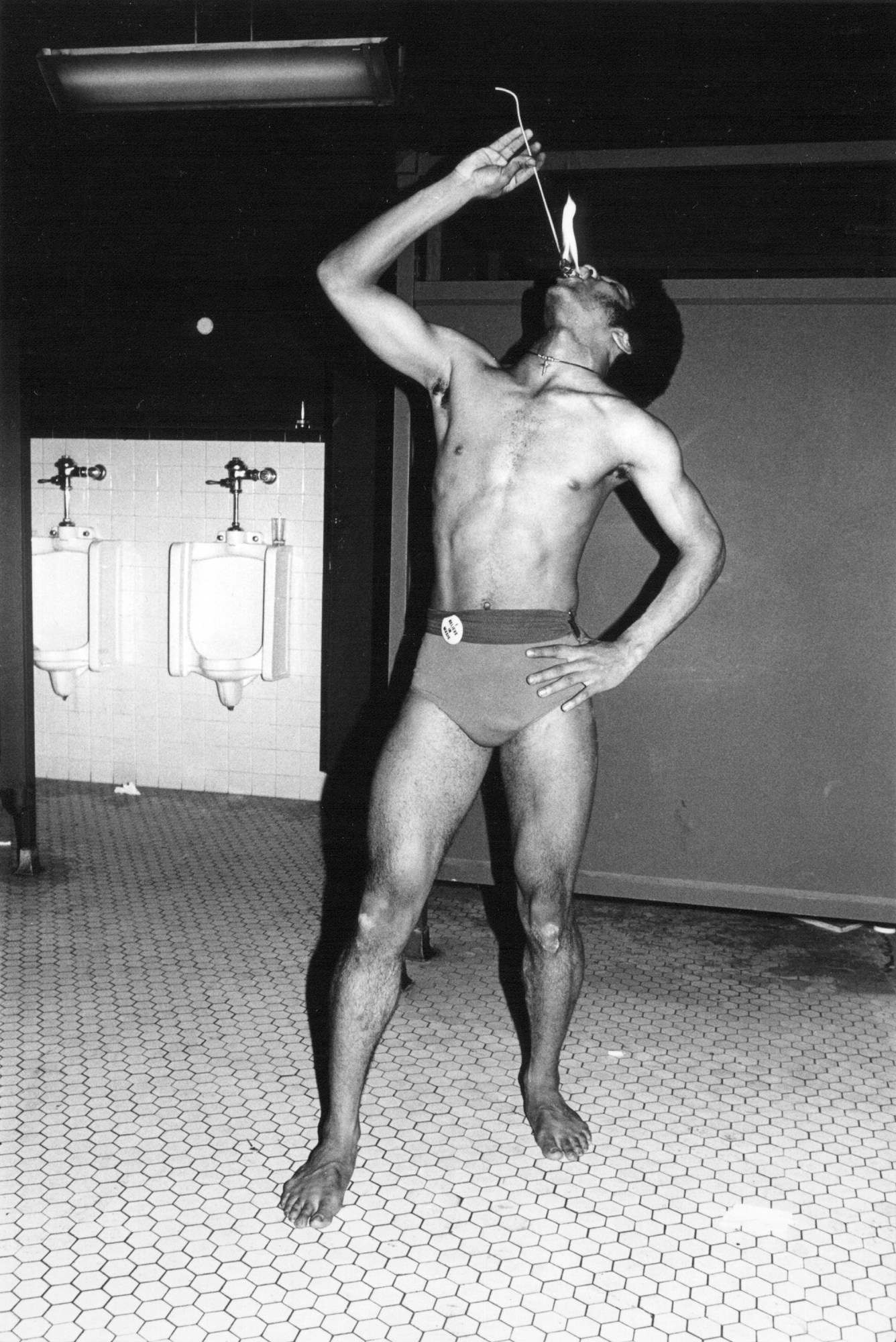

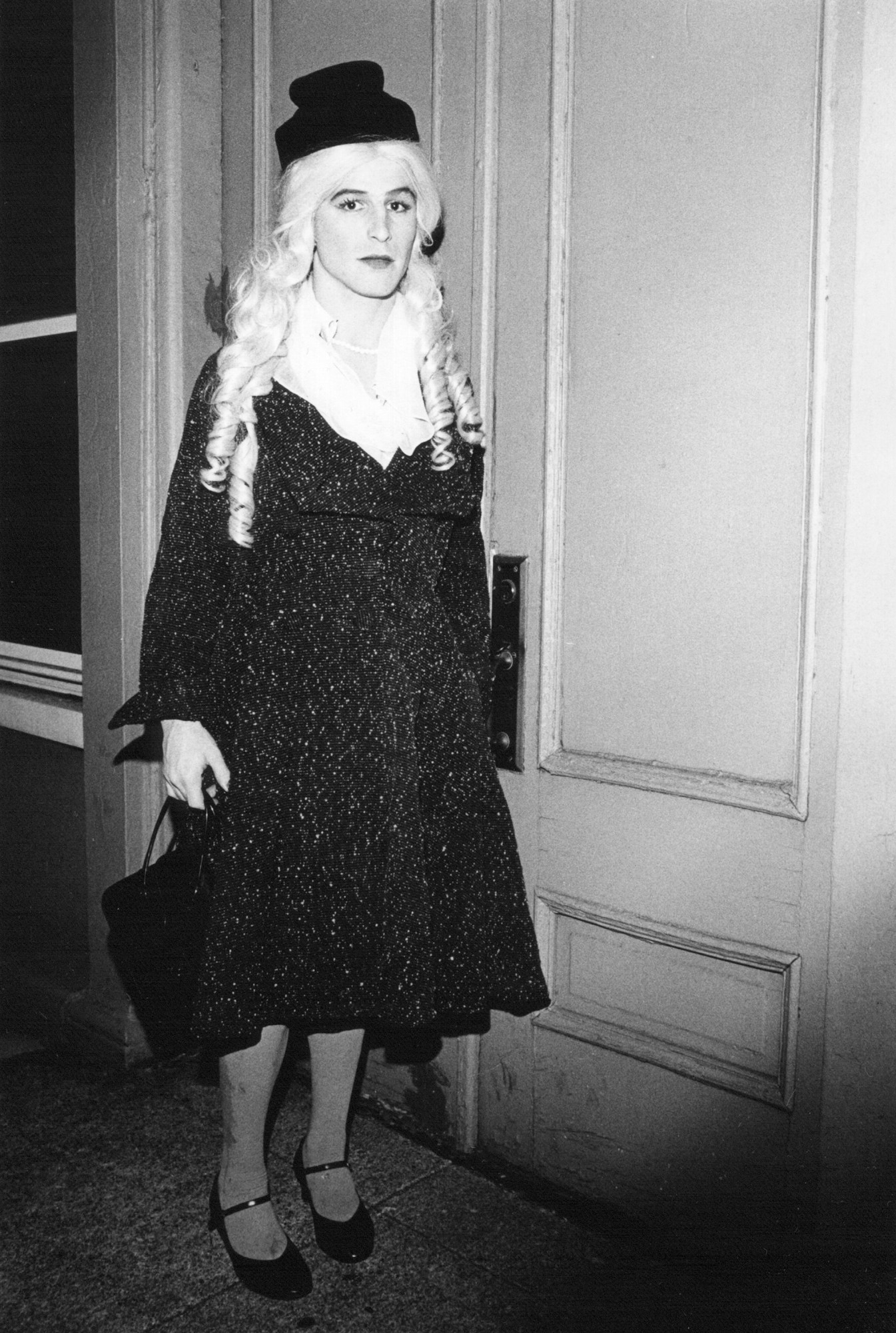

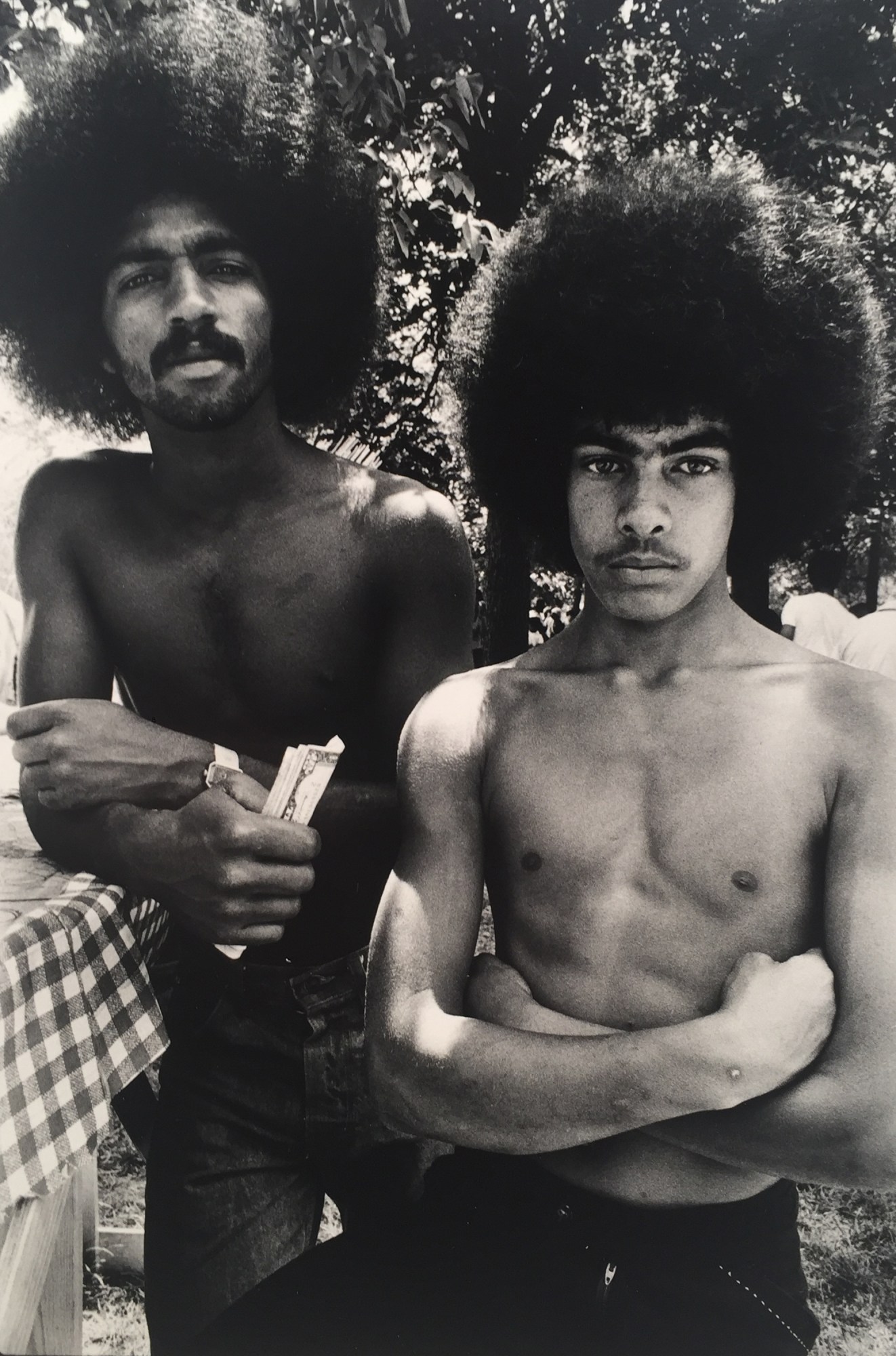

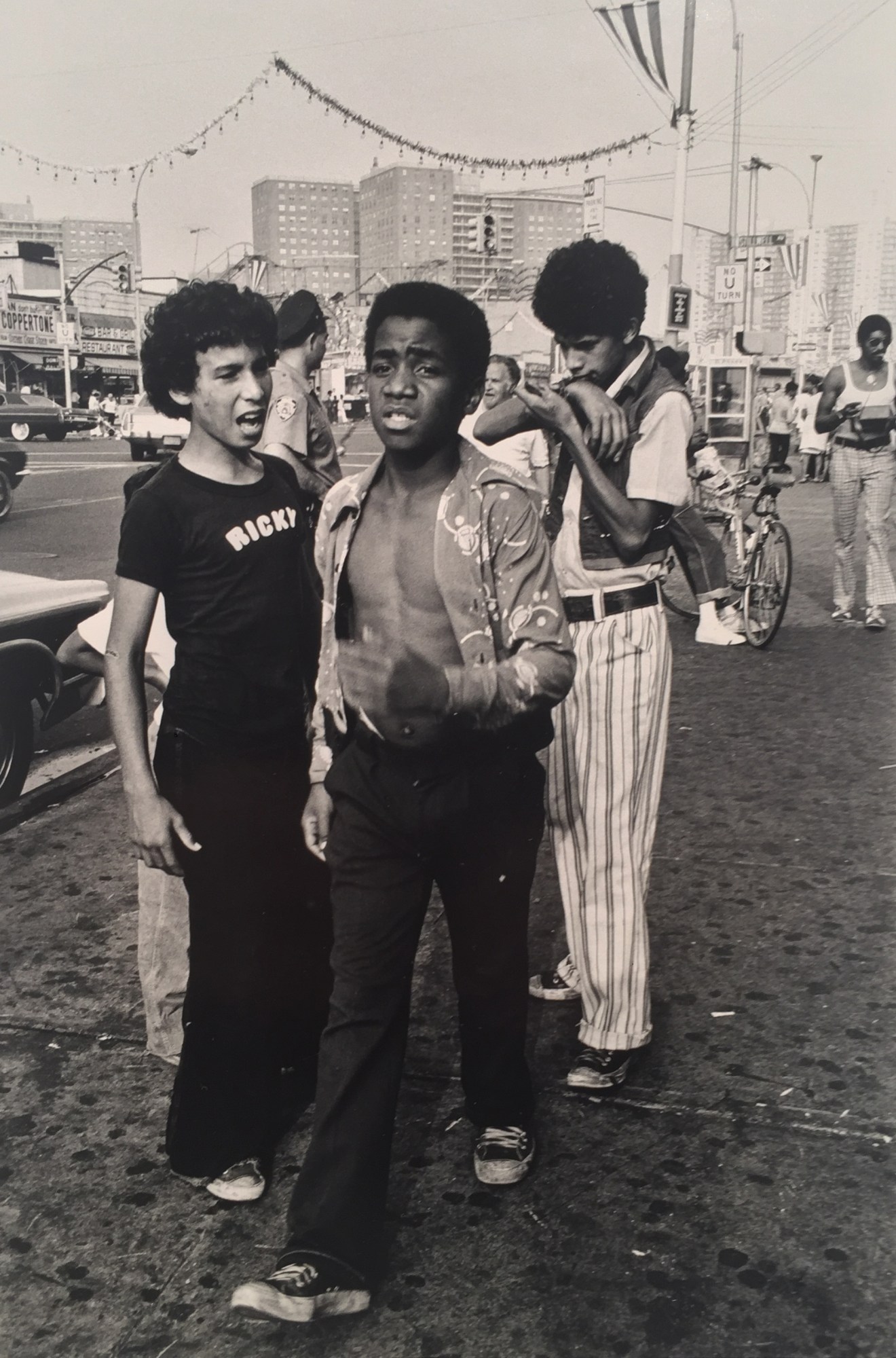

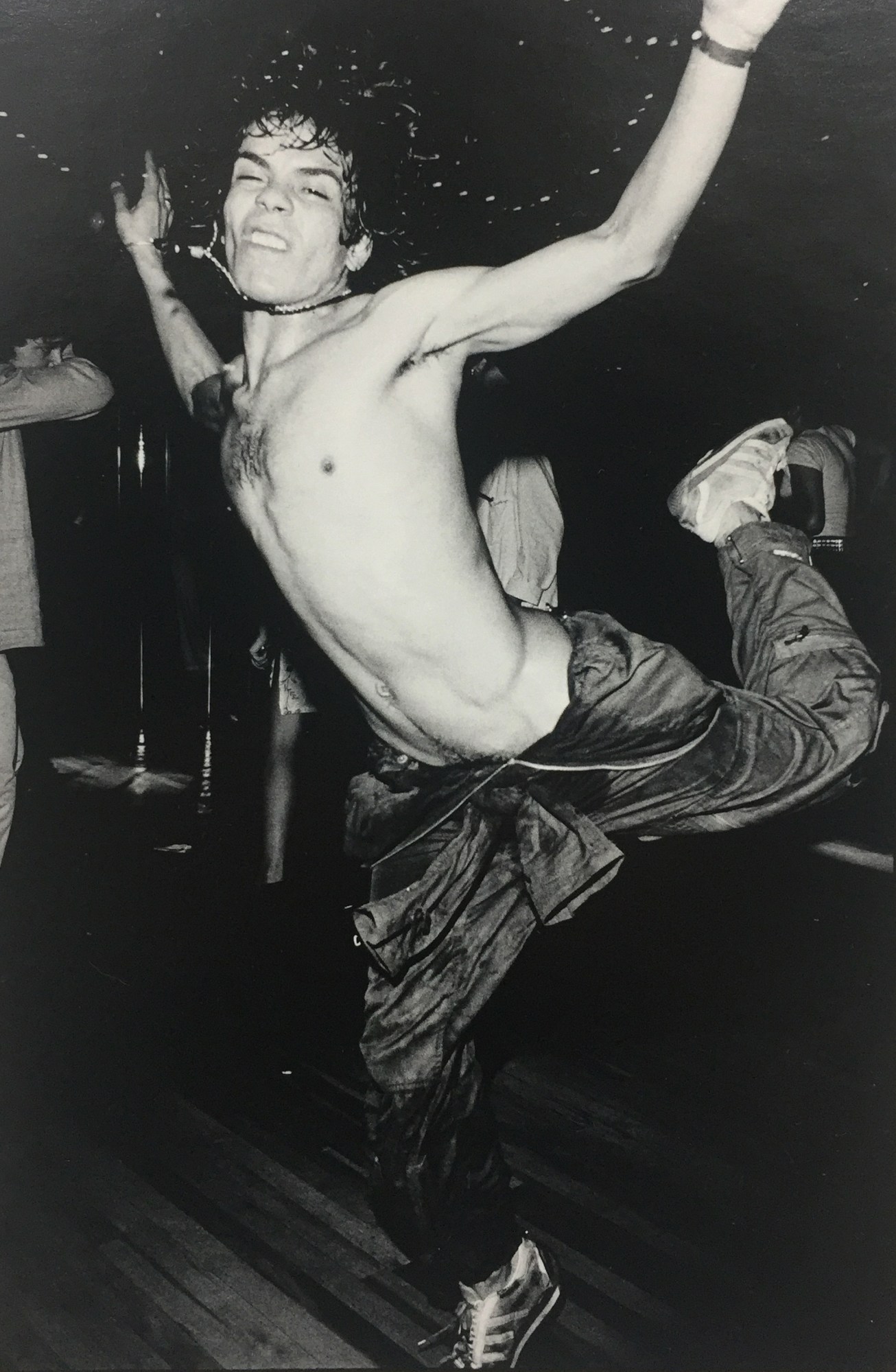

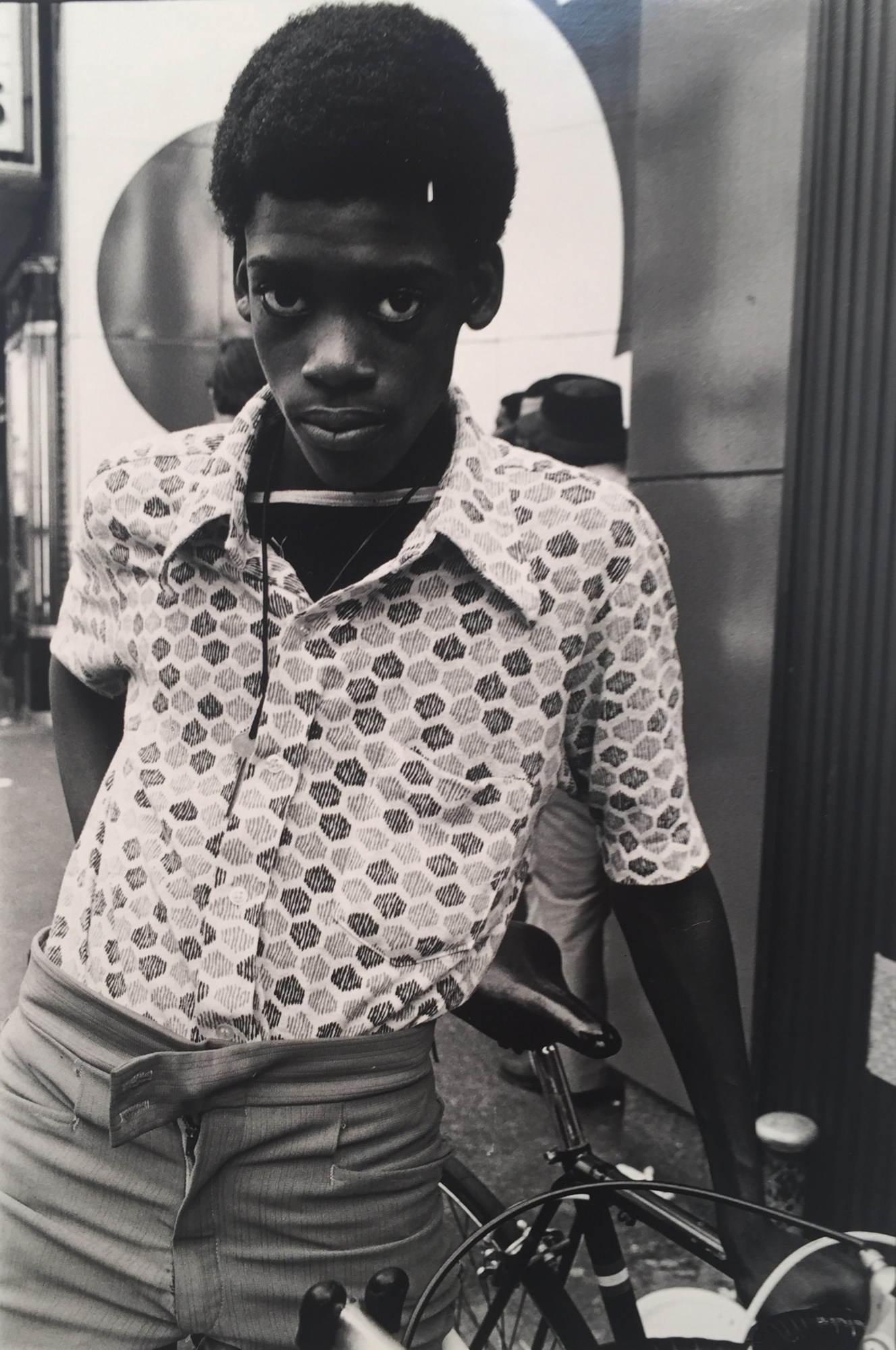

She photographed Hasidic children disguised in Purim costumes, and the ceaseless parade of eccentric sunbathers passing through Coney Island. (Gottfried lived in the South Brooklyn beach town until she was nine years old, in an apartment above her father’s hardware store). When her family relocated to Alphabet City, she turned her lens on the Lower East Side’s Puerto Rican community. “There’s also a huge amount of wild nightlife pictures at Studio 54 and G.G.’s Barnum Room in Times Square,” Cooney explained, showing me photographs of Diana Ross, Rick James, and Stevie Wonder.

On the subject of singers, Cooney tells me of Gottfried’s gospel work. She spent months documenting Harlem’s Eternal Light Community Singers, an African American choir she first heard sing at a gospel gathering staged in an abandoned gas station. The images formed the first of Gottfried’s five books, and she ended up joining the choir. “My mother started calling her ‘The Singing Photographer,’” Arlene’s brother, esteemed comedian Gilbert, told me. (She printed this title on her business cards).

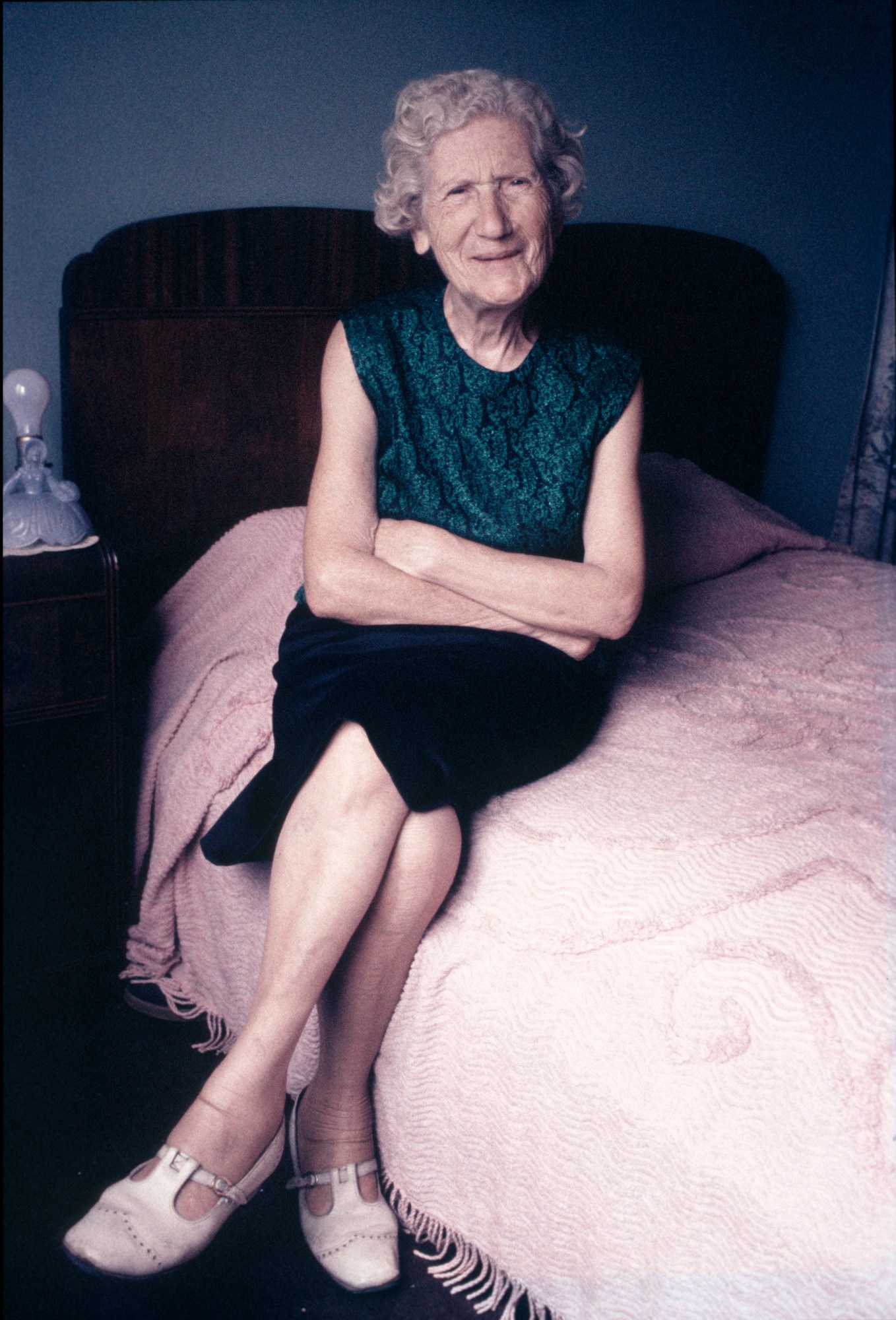

No matter who Gottfried photographed — or where she happened upon her idiosyncratic subjects — she documented friends, strangers, and family with honesty and empathy. “If Diane Arbus photographed these people, they’d be freaky. But Arlene likes these people!” Cooney laughed. “She’s always making eye contact with them. Consistently, they know they’re being photographed. Her images have a great sense of humor, but it’s never critical or sarcastic. They’re very affectionate.”

Gibert agreed. “Recently, my wife and I were walking down the street, and we saw a homeless man helping another homeless man sit up. He had his arms around him in such a way that both of us had the same reaction: ‘That would be an Arlene picture,’” he remembered. “She’d see something that other people would be horrified or depressed by. Or just find it strange. But she was never one to judge. It was always with love.”

Ahead of A Lifetime of Wandering’s opening tonight, Cooney shared more about his journey through Gottfried’s archive.

How did you first meet Arlene?

Through Paul Moakley, a photo editor at Time magazine who I’ve known for quite a while. He’s the caretaker and sometimes curator at the Alice Austen House, and he invited me to a show he’d done with Arlene. They were close friends, and he introduced us. [Later], she came into [my] gallery with a rolling suitcase of her work, and took out her Sometimes Overwhelming book. She had the prints with her, too. It was amazing. I decided, right there, to start working with her. We planned her first show with the Sometimes Overwhelming work — black and white, mostly New York City street photographs — and it was very successful.

At that point, I was probably seven years into the gallery. I’d always worked with emerging artists and younger artists doing first shows. But Arlene was the first artist I showed who had an incredible lifetime of work behind her. Now, that’s kind of what I do. I work with photographs from that 70s-80s era that have been overlooked.

That’s true. You’ve exhibited Gail Thacker’s Polaroids , Len Spier’s first show , Anthony Friedkin .

Arlene was the first artist I did that with. She was an amazing person, and my experience with her work changed my life, in a way. It definitely shifted the focus of my gallery, and set me on a new path, which is so rewarding. She showed me the way.

You did another show with Arlene, too.

Yes. Both shows were based on her books. Sometimes Overwhelming was the first, Bacalaitos & Fireworks was the second. I brought up the idea of doing another show to Arlene last March or April. I said I wanted to spend the summer visiting her every week or two, and going through her full archive to find work people haven’t seen. We agreed to do it, but she started not feeling well. We postponed the visits, and then she passed away in August. I suggested to her family that we move forward with the show. I told them exactly what we were thinking, and they were on-board. But I really missed her humor, and I asked for her guidance every time I went into the space.

I didn’t know about Arlene’s work until you sent me an invitation to Bacalaitos & Fireworks. I couldn’t believe I’d never seen her photographs before. Why do you think her work is little-known?

It’s partly because of how humble she was. Arlene really did not like to talk about herself. She wasn’t going to be out there shaking hands or sending her work to people. That just wasn’t her at all. Also, she attended F.I.T. around 1968, 1969. She told me she was the only woman in her classes, and she definitely didn’t have any female teachers. So I think another part of it could have been because she was a woman in the photo industry during that time. And maybe there’s a certain nostalgia to her work now that wasn’t really true then. Now, we want to look back at New York City in the 70s and 80s, when it was dirty and grimy.

How vast is her archive?

It really is a lifetime of work. There are extensive photographs of heroin addicts on the Lower East Side. Pictures of Puerto Rico, Cuba, Rome, London. There’s also the Midnight work. Arlene photographed a friend of hers named Midnight for 15 years. He struggled with schizophrenia and was institutionalized, both in mental hospitals and prisons. In 2003, she published a Midnight book of all color photographs. When I was looking through her archive, I found this huge amount of beautiful black-and-white Midnight photographs that no one even knew about. I called the publisher and asked all of her friends, and no one had ever seen black-and-white Midnight pictures.

How did you go about making the edit?

I went in with a thought that it would be a mini-retrospective. Then, I started to realize how much work there was. I came to realize: all I had to do was put the best pictures aside and let them tell me what the show was going to be. Sounds a little weird, but it’s true. I’ve included a few greatest hits, but I was definitely keeping an eye out for work I knew people haven’t seen before. Arlene was at her best when she was connecting with people’s vulnerability. I think that was really her gift.

Did she ever talk about why she was drawn to the people she photographed?

Not to me. But she was always photographing communities and people that were under-recognized or underrepresented. Perhaps she felt like an outsider in some way. She really identified with people that were a little bit on the fringes.

What was the most challenging aspect of putting the show together?

I miss her! I wish she was here. I’ve had moments where I meditate, ask for guidance, for her to come with me. Because the show is representing her life. I take that really seriously. On a different level, the challenge is that I want her legacy to move forward. People are being really supportive. There are collectors who love her work, and she’s recently been included in great shows and books. Now, it’s about trying to get the world to recognize her. It’s a challenge, but also an honor.

‘Arlene Gottfried: A Lifetime of Wandering’ is on view at Daniel Cooney Fine Art through April 28.