The Brooklyn Museum’s “Nobody Promised You Tomorrow: Art 50 Years After Stonewall” is commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising, while also shining a light on individuals and details of this historical movement that have been typically left out of popular media.

The exhibit, which is a collaborative effort from a group of curators including Margo Cohen Ristorucci, Lindsay C. Harris, Carmen Hermo, Allie Rickard, and Lauren Argentina Zelaya, features artwork created by 28 LGBTQ+ artists who were all born after the 1969 Stonewall Uprising occurred. Their pieces explore a myriad of important themes such as identity, the significance of care networks in queer communities, the effects of gentrification on these marginalized groups, and more, while also honoring the continued fight for queer liberation and the fearless activists who helped create and cultivate this movement throughout the years.

In honor of this exhibition which is on view through December 8, i-D spoke with four of the curators about the importance of remembering Stonewall, how caring for each another can be a radical act while faced with oppression, and how the fight for equality still continues on today:

What was the process like of putting this show together?

Lindsay C. Harris: The process of curating collectively was queerly organic and life affirming. In education, I work with LGBTQ+ young people of color and was excited to bring them in into this process. Margo, Allie, Carmen, and Lauren were likewise eager to bring their own personal and professional experience to this new curatorial project, building on Brooklyn Museum’s legacy of working with queer and trans artists most notably in Public Programs and Education, and the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art’s history and opportunity for black feminist, intersectional and transfeminist shows.

We started out a year and a half ago with ideas and artists in mind, those who we knew were doing incredible work in our community — whether working with them previously through public programs, like Linda LaBeija; seeing their work in galleries or fairs, like Jeffrey Gibson; being in community with them through QTPOC parties, like Mohammed Fayaz; or through our own research or recommendations from other artists.

Why do you think it is important to have included artists that were specifically born after Stonewall?

Carmen Hermo: For us, curating this show in 2019 in the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, we were interested in exploring the legacy of the uprising by asking what it means to live and make work in the post-Stonewall era. We wanted to root a commemoration of this historic event very firmly in the 50th year, specifically through an understanding of the conditions and concerns of queer and trans artists working today that connect us back to that moment, and inspire us to care for tomorrow’s generations.

Can you walk us through some of the artworks and the symbolism found in the pieces?

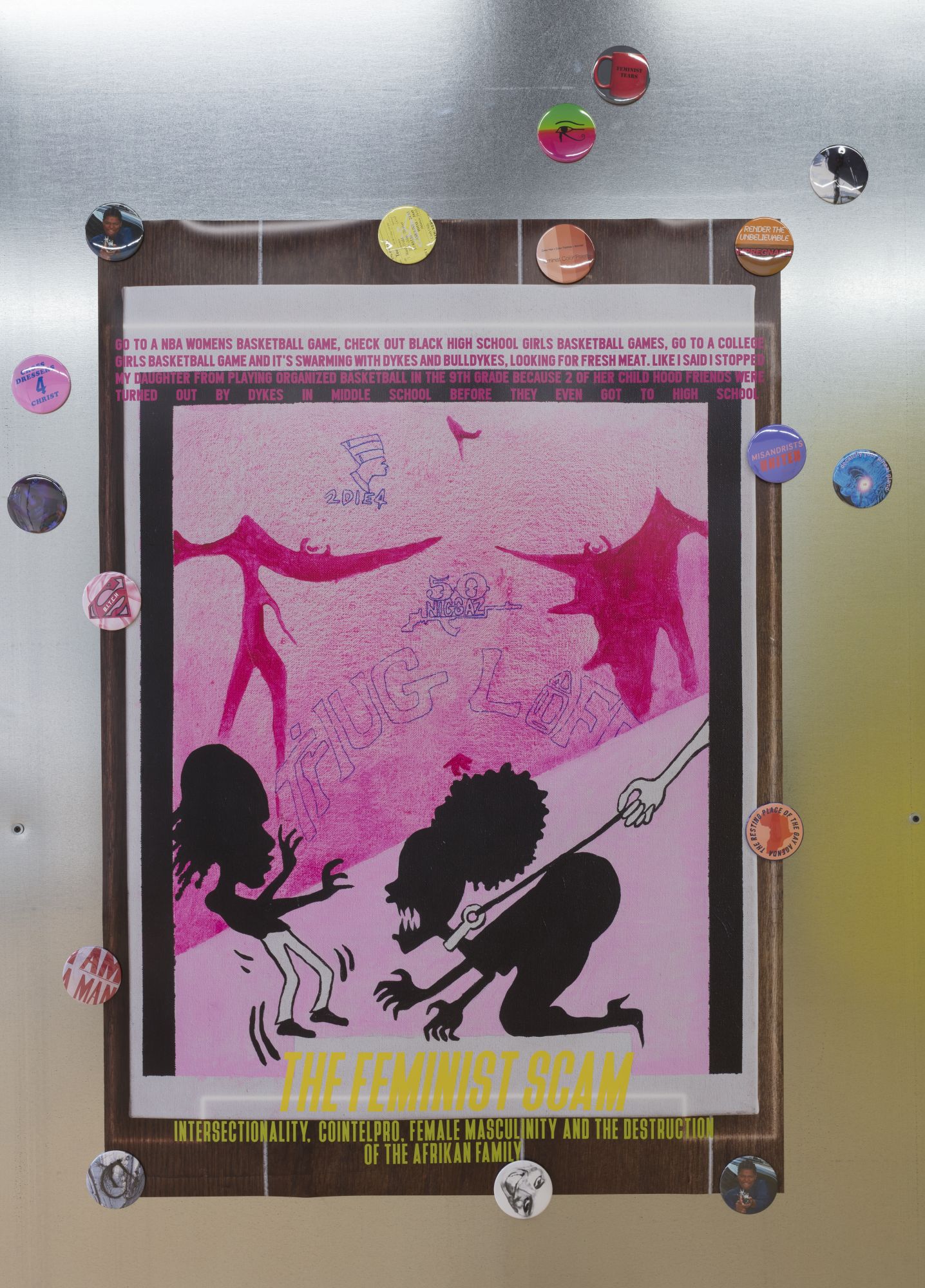

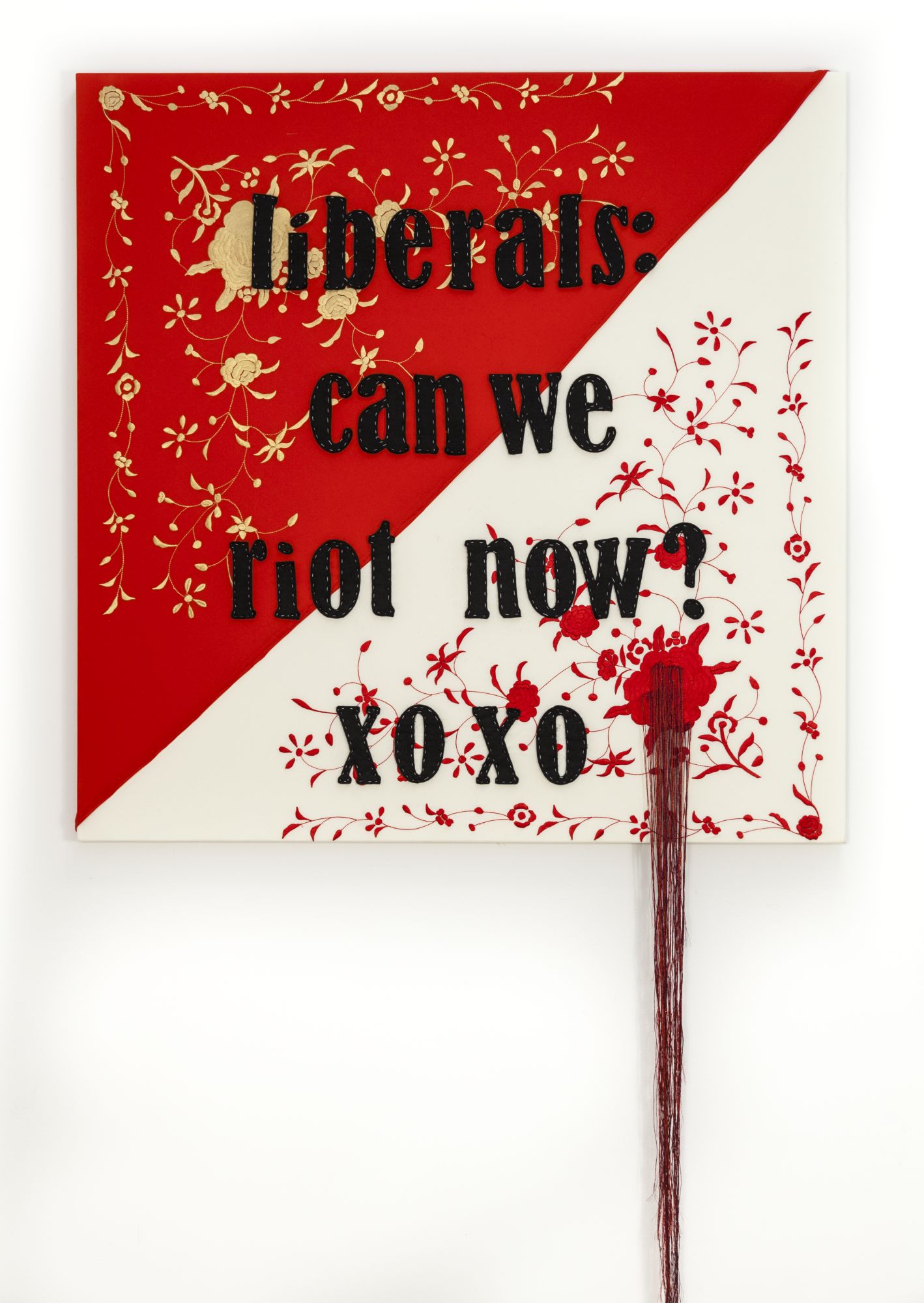

Margo Cohen Ristorucci: The artists in the exhibition at once pay tribute to rich histories of queer and trans life and activism, and face the future — imagining worlds beyond our current interlocking systems of oppression. The works of art are organized into four intersecting themes: Revolt, Heritage, Desire, and Care Networks.

Tourmaline and Sasha Wortzel’s film Happy Birthday, Marsha! opens Revolt. In this speculative film, the artists imagine the ways in which Black trans activist and artist Marsha P. Johnson, whose words inspired the title of the exhibition, spent the hours before the Stonewall Uprising ignited.

In Heritage, Tourmaline’s new film Salacia looks further into history. In the style of Black fantasy and folktales such as Virginia Hamilton’s The People Could Fly, Salacia follows Mary Jones, a Black trans New Yorker who lived during the early 1800s, as she harnesses her spiritual power and the support of Seneca Village (a free Black community in upper Manhattan that was razed to later create Central Park) to navigate intense systemic racism and transphobia. LJ Roberts’s monumental sculpture of fourteen light boxes Stormé at Stonewall honors Stormé DeLarverie, a biracial butch lesbian and performer who was believed by many to have thrown the first punch that started the Uprising, while simultaneously questioning this desire to ascribe credit to specific individuals and create singular narratives around historical events.

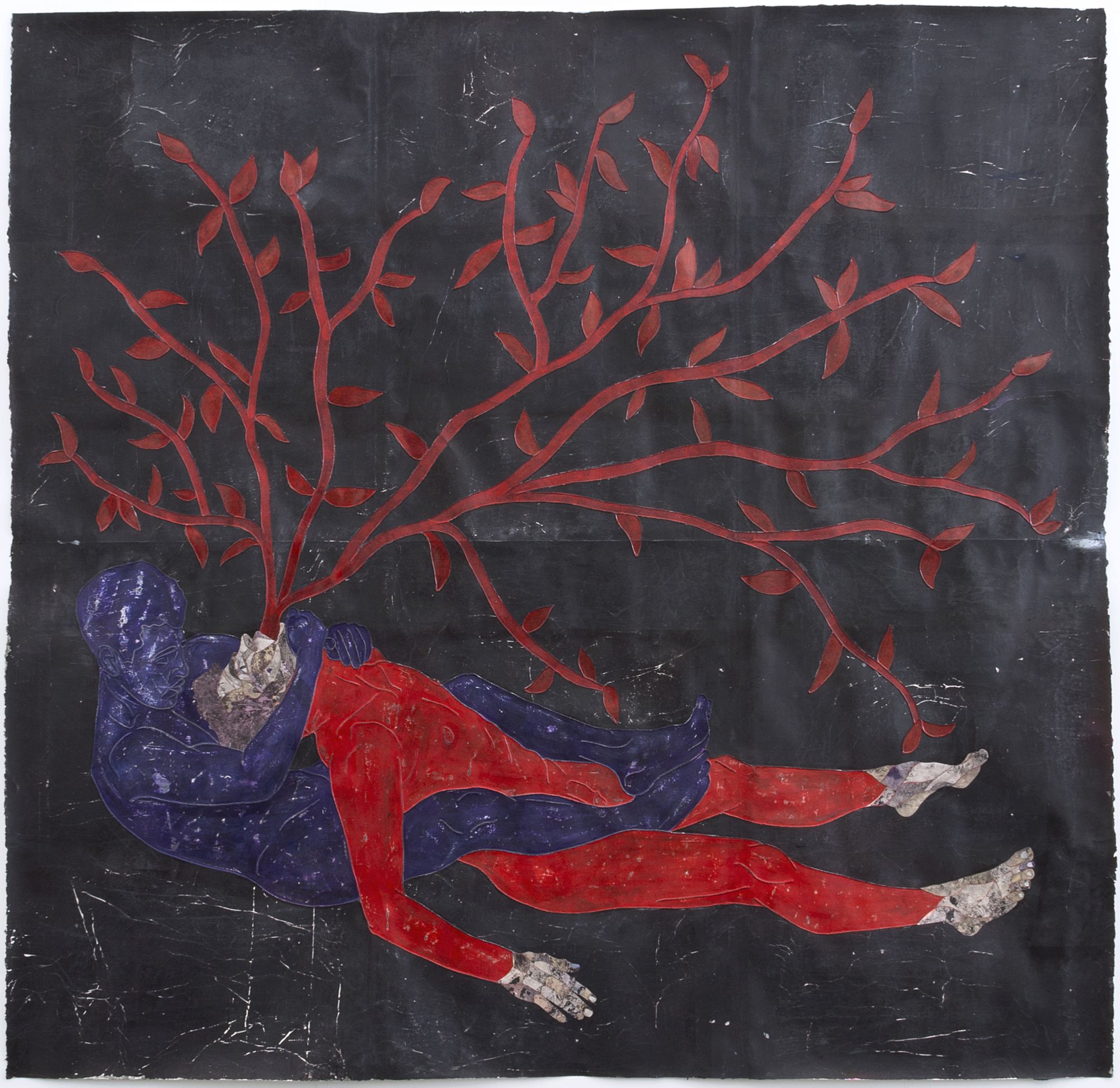

Looking toward tomorrow, Amaryllis DeJesus Moleski’s exuberant works on paper in Desire envision futures wherein femmes of color lead. Mark Aguhar’s I’d rather be beautiful than male articulates in gouache and glitter desire to live beyond binarized gender. And in Care Networks, the installation Lavender Hill Historical Society—collectively created by Morgan Bassichis, Anna Betbeze, TM Davy, DonChristian Jones, Michi Ilona Osato, and Una Aya Osato—celebrates Lavender Hill, a queer commune founded outside Ithaca, New York in the late 1960s, and playfully engages archives of chosen family.

What are some current issues these artworks address?

Allie Rickard: Many of the issues which led folks to rise up in the summer of 1969 continue to persist and remain critical issues in the present. Artists in the show address racism, police brutality, state-sanctioned violence, homelessness, gentrification, and displacement. In doing so, they help us to consider how persistent forms of systemic violence and oppression, especially against trans and gender-nonconforming people of color, have gone unaddressed by the mainstream Gay Rights movement, and how organizing to resist and dismantle these forms of oppression has a long history within queer liberation and antecedents such as STAR (Street Transvestites Action Revolutionaries) founded by Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera.

5. Why do you believe it is important that we never forget impactful historical events such as Stonewall?

AR: We hope this exhibition fosters a critical remembrance and commemoration of historical moments and movements like the Stonewall Uprising and queer liberation. So often signal moments in history are monumentalized in such a way that systemic forms of violence and erasure are perpetuated in their historicization — we might think of how the Stonewall Uprising has been whitewashed and gender-washed in mainstream histories with trans and gender-nonconforming folks of color being erased from their central role in the Uprising, and the fact that gender-nonconformity was actively policed at that time with the three articles of gendered clothing law. So, while it is important that we never forget a moment like Stonewall, it is equally, if not more important, that we remain critical of the ways in which we do remember — who do we remember and why? Who is telling the history of Stonewall and who is not? Many of the artists in Nobody Promised You Tomorrow turn their attention to individuals and communities left out of these mainstream histories of the Uprising including Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera in the work of Tourmaline, Tuesday Smillie, and Sasha Wortzel, and Stormé DeLarverie in the work of LJ Roberts.

While preparing for the exhibit, was there anything surprising or interesting you learned about Stonewall and its history that people may not be aware of?

CH: While researching the Uprising and its context, I was struck by how the Stonewall Uprising’s symbolism in the LGBTQ+ civil rights movement is in stark contrast to the mainstream perception of the 1960s as a time of radical social action due to the work of communities of color, women, peace, and environmental movements. Though actions in Philadelphia, San Francisco, and New York preceded the days and nights of rebellion around Stonewall, this July 1969 moment coalesced into a major challenge to the status quo of what is rosily remembered as a decade of change. In reality in 1969, there was not a single law — local, state, or federal — protecting LGBTQ+ people at work, and charges of “indecency,” oral and anal sex bans, and gender presentation laws menaced lives every day.

MCR: While Nobody Promised You Tomorrow focuses on a constellation of 28 queer and trans artists born after 1969, and creating work in the new millennium, visitors may be surprised by the expansive sense of time represented across the exhibition. A pair of lushly pigmented paintings Naj Tunich (Azul 1) and Naj Tunich (Azul 2) by Felipe Baeza, for example, take inspiration from a Mayan cave painting of two men embracing dating back to 250 – 900 c.e. Though the exhibition developed from a desire to engage the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising, the artists underscore that queerness is ancient and ancestral.

What do you hope visitors take away from viewing this show?

AR: I hope visitors feel the importance of care within the exhibition and within queer and trans community. If we think expansively of care as acts of affection, love, and support — both material and immaterial — between friends, lovers, activists, and collaborators, we can see how care is a vibrant force within friendships, companionship, and chosen kinship. For queer and trans communities, caring for one another can be a radical act in the face of oppression, violence, and discrimination. Our strategies of mutual support are vital and have sustained us throughout history and into the present. Whether it be at a bar, at the beach, or while living collectively with other queer and trans folks, care can be exuberant and life-giving. We might also think of the Uprising itself as an act of care — not only by those involved who took action out of rage and love to come together for their community at the time, but also as an act of care for future generations of queer and trans folks living after 1969 in the legacy of the Uprising.