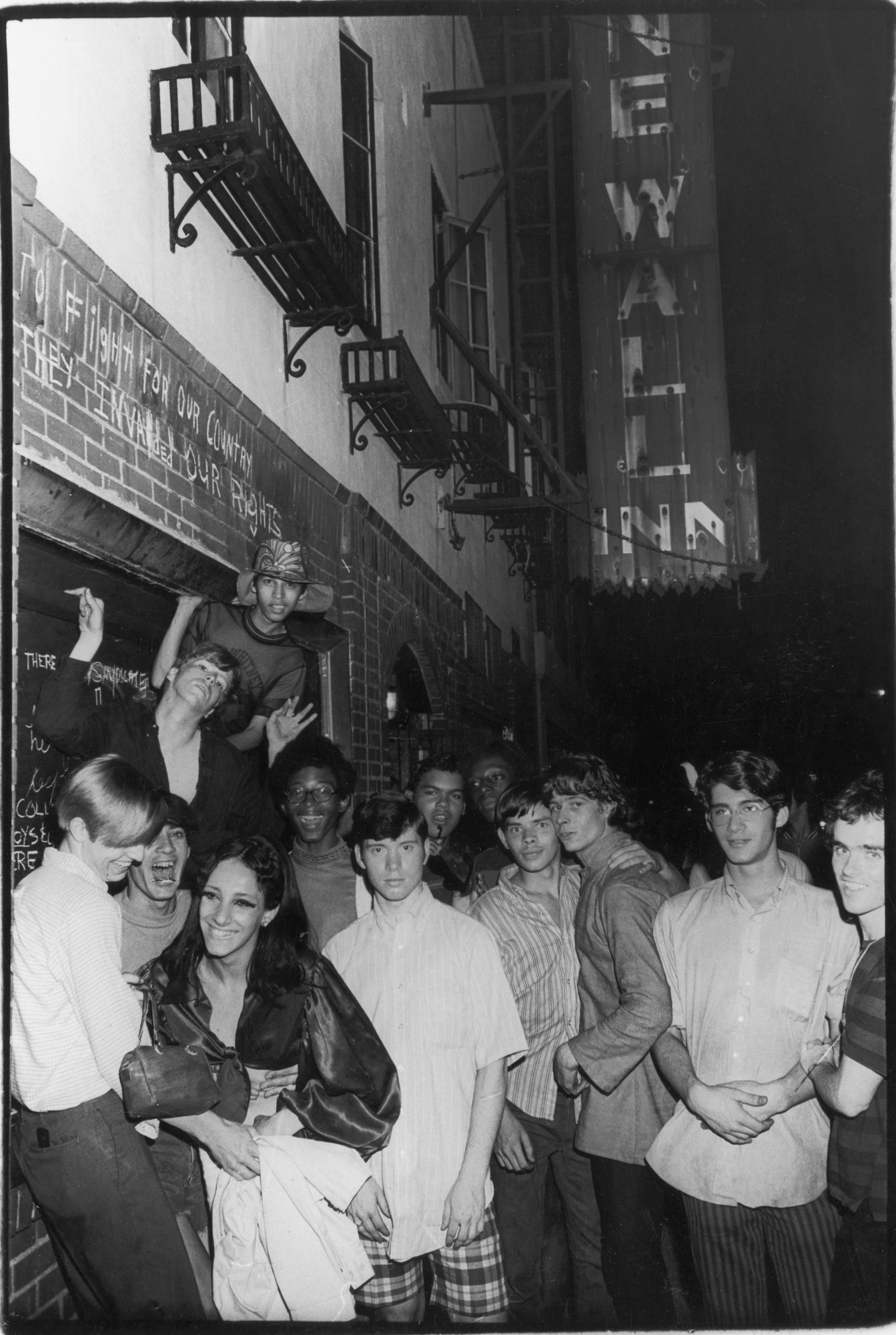

It’s hard to believe it’s the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots, which became a catalyst for gay rights after police raided the Stonewall Inn in 1969. Looking back, we remember the historic protests through photos of protesters holding signs like “3,000,000 homosexuals demand justice” and “Stonewall means fight back! Smash gay oppression!”

Beyond the news reports, what memorializes this moment in LGBTQ history from the voice of the art community? Art After Stonewall is a two-part exhibition showing the mostly overlooked artworks, opening April 24 at the Leslie Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art and the Grey Art Gallery, both in New York.

Featuring over 200 artworks, there are photos by Nan Goldin, Robert Mapplethorpe, Catherine Opie, as well as works by Harmony Hammond, Greer Lankton, and Andy Warhol, alongside newspaper clippings, TV clips, and ephemera from 1969 to 1989.

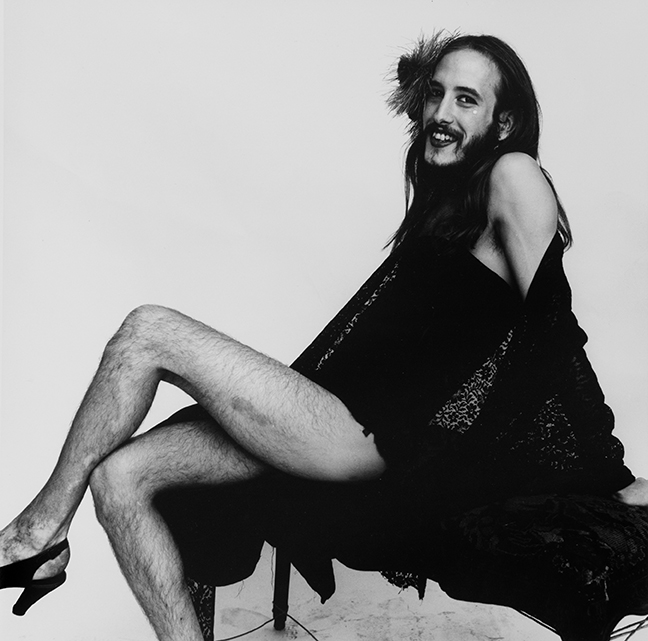

They all detail the impact of the gay rights movement across the world, and the exhibitions are themed around AIDS, activism, gender fluidity, and coming out. There will also be a book release with Rizzoli, which traces 200 artworks made before 1990. i-D spoke to co-curator Jonathan Weinberg about this exhibition, which travels next to Miami and Columbus, coming out, Keith Haring, and the roots of resistance art under the Trump administration.

Why this, why now, 50 years after Stonewall?

Well, it’s in the village, it’s the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots, only 15 blocks from where they took place. The main question is: What is the role of art, the visual in this show? The first theme is coming out. How important visibility is to the movement. LGBTQ history didn’t start in 1969, it has a long, complicated history. There was this idea that the Stonewall riots happened in 1969, but the decision was it should be memorialized. It represented a turning point. The year later when the first Pride march happened in Chicago, then New York, more came about as the years went on. There was not only news about the march, but poetry, art, and photography. The notion of visibility to that kind of work is a huge part of the exhibition.

Can you give some examples of works in the show?

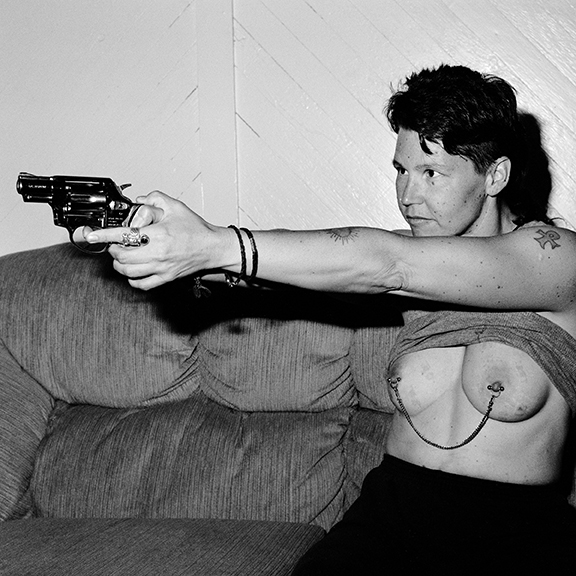

There’s a lot of images of people kissing or embracing, it’s a political action. We have street artists like Keith Haring and works by Linda Benglis, who did the 1974 Artforum photo ad with a dildo, but people didn’t think it had a queer reference, but it was a sex toy same sex couples were using. There are photos by Nan Goldin, Peter Hujar, and Catherine Opie. It was so important the first Pride march was photographed. Today, it’s important because it’s a model for resistance. It sustains a movement. Some people think political art needs to change people’s minds, but it’s about hope and keeping them going in the struggle for rights.

What’s one of your favorite pieces?

Peter Hujar’s 1970 photograph, the “Gay Liberation Front Poster” image, showing a group of people running down a street, which was created by a group of people on an early morning in New York to make it look like they were taking over the streets, when they weren’t. It was just made to look like that. It became an iconic image of the early gay rights movement. It shows why image-making is so important in a movement. It’s a part of community.

What characterized LGBTQ art after Stonewall and the years after?

Ten years after Stonewall you have the AIDS crisis, the whole notion of queerness took off in 1980. We’re not into labels, it’s about the art. It’s not about someone being what, it’s about what the art is about. There is a question of categories. Something that is noticeable is people who died from HIV who are not with us who are in the show. Coming out it still difficult, it matters.

What did Gran Fury’s ‘Riot’ stickers mean back in 1989?

We put that in because it plays in on the Robert Indiana Love piece from the 60s. Another group had an AIDS stamp. Gran Fury turned this idea of love into a riot. They created posters, stickers, but the sticker wasn’t used at the time that much, it links 1969 to 1989, the beginning with the end of the show.

How does it tie into what’s happening now in 2019?

To me, the message of the show is this idea of resistance and community. How do you deal with enormous repression? We are in a moment of horrible psychic trauma the current administration is doing to us. It may seem overwhelming to us. The show is all about people facing similar trauma and coming together, that would be the message of the show. I don’t know how well-versed people are in the AIDS epidemic, it was a nightmare. One thing that worries me about the exhibit is that we’re celebrating the 50th anniversary of Stonewall, which creates a sense of unity. That’s not the way it was, there were so many different sub-movements, but that’s part of it. It shows you the coming together of the groups. The point is looking back and seeing how they made it through somehow.

Can you explain the story behind Keith Haring’s “National Coming Out Day” piece?

That poster is at Leslie Lohman Museum, while the Grey Art Gallery has a sculpture of a closet by Robert Gober, which had to be installed in a wall. You have these two comparisons; it raises the question of gender fluidity. Haring’s marshmallow figures, it’s joyful. This poster was targeted for college kids. I say that because I came out in college because of National Coming Out Day. It was crucial for my coming out in the 70s. Are you in or out of the closet? But once you’re out, you’re out. But I’m out all the time. If I call the cable company and I mention my husband, it’s an act of coming out, same as when I come out to my students when I teach a new class.

Was Keith educating people through his art?

Up until the moment he died, he was working on incredible projects with kids, working against drug addiction, tirelessly doing that. He’s an inspiring person and he fought censorship, which is a part of the show. This exhibition is a chronology of 20 years and there’s a lot of overlap. There is no strict chronology. We did want to end with this notion of ‘we are here.’ It’s about making yourself visible and coming out at the end, it says, “We’ve been here all along. We’re here, we’re queer, get used to it.” We thought that was a great way to end it.