“Donald Trump’s presidency represents a great danger for many people in the United States,” says Gregg Bordowitz. His tone is calm, but his delivery is firm. We’re sitting in the café of Jumex Museum in Mexico City, where he’s giving a talk on the legacy of the Canadian art collective General Idea, to coincide with their current retrospective. “I didn’t think it would be possible to imagine a worse presidency than Reagan’s, and now I feel thrust back into very dangerous situations where we have a president who is xenophobic, racist, homophobic, and sexist. He’s demonstrated in the first few days of his office that he is a tyrant.”

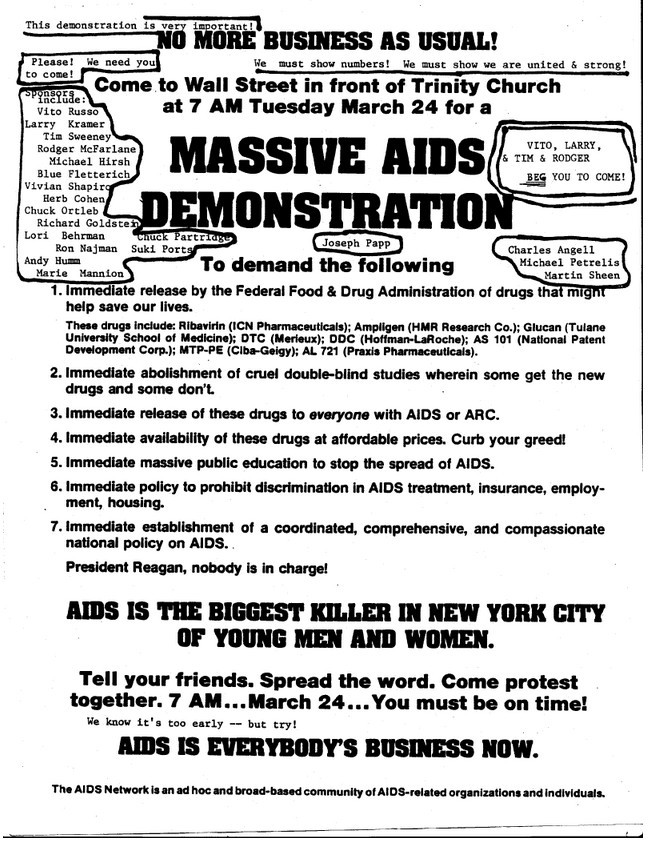

In 1987, Bordowitz, then a 22-year-old NYU student, found a leaflet for the first protest organized by ACT UP (the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power). He joined the demonstration, along with 250 other activists, to demand greater access to experimental AIDS drugs and a coordinated national policy to fight the disease. Frustration and anger were growing as Ronald Reagan refused to acknowledge the epidemic that had already wiped out over 40,000 people in the US alone – evidence of the politics of fear and discrimination that came to define his administration. The activist group adopted the now-iconic slogan Silence = Death, which had spontaneously appeared on posters across the city, adorned with an inverted pink triangle appropriated from Nazi concentration camp badges used to identify homosexuals. Soon after, Bordowitz tested HIV-positive.

“When I became involved with AIDS activism, it became apparent that I had a set of skills that I could use,” remembers the Brooklyn-born artist, who had studied video at the School of Visual Arts. “Even though I’d been to art school, and was serious about becoming an artist, the AIDS crisis demanded my entire attention and shifted the focus of my work.” Bordowitz dropped out of college and started to film the demonstrations, soon forming the video group Testing the Limits with fellow filmmaker David Meieran, who he’d met while attending the Whitney Museum’s Independent Study Program. “We had this idea that if we represented what was going on, and edited it into a coherent [film] to screen to activists, we could help document and foster the growing coalition.” Bordowitz went on to take up active roles in the Gay Men’s Health Crisis cable TV show Living with Aids and co-found ACT UP’s partner organization DIVA (Damned Interfering Video Artists).

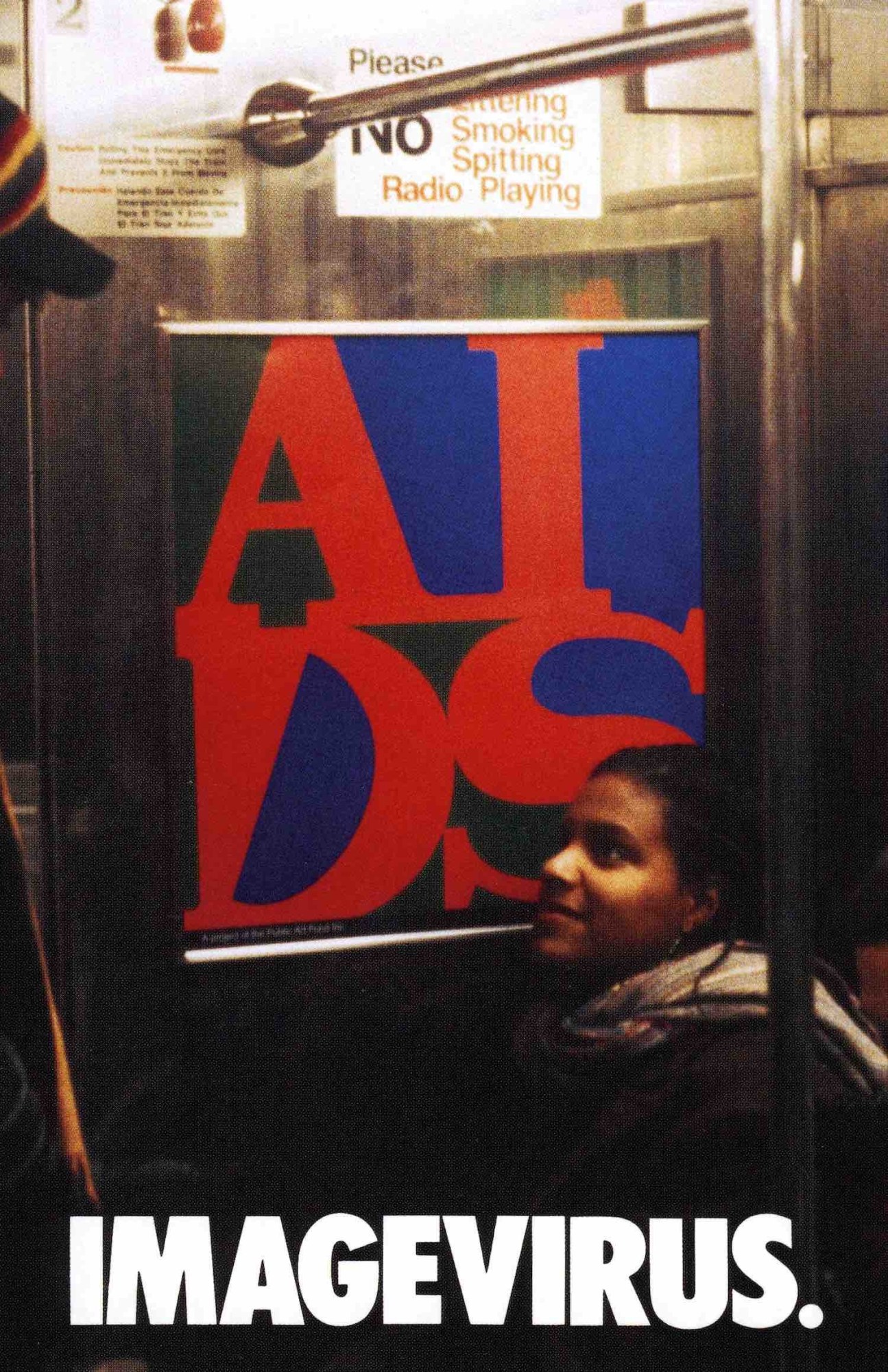

Around that time, a controversial series of works appropriating Robert Indiana’s “LOVE” logo and replacing it with the letters A-I-D-S cropped up around New York and, soon after, across the world. Imagevirus, the title of the work, was initially conceived as a painting in 1987, and was later replicated in various formats – as subway posters, public sculptures, an animated billboard on Times Square, as advertising banners on Amsterdam’s trams – all using the mechanisms of “viral transmission.”

Behind the intervention was conceptual art collaborative General Idea, formed by AA Bronson, Felix Partz, and Jorge Zontal (both Felix and Jorge died of HIV-related complications in 1994). The work proved divisive, causing a stir among the activist community, who found it in “bad taste” at best, and, at worst, too distanced from the pragmatic needs of the movement. “Frankly, the work was above my head,” recalls Bordowitz, who wrote a book reflecting on the work in 2010. “It was just not the work, or the strategies, that I was focusing on.” The art collective Gran Fury, closely associated with ACT UP and known for its raw, overtly-political guerrilla work, soon responded with yet another appropriation, now rendering Indiana’s logo as “RIOT,” summing up the tense dialogue between distinct groups of artists invested in AIDS activism.

But General Idea’s anti-establishment art emerged from a very different context than that of their younger peers. It came out of the Canadian communard counterculture of the late 1960s, at the height of the Gay and Lesbian Liberation Movement. “[General Idea] were part of a very large group of people who were disillusioned with protests and marches. They had come to use humor, irony, and the notion of the prank,” explains Bordowitz. “I think it’s interesting to consider some of the tactics that General Idea use, that made them such a radical group.”

As the epidemic peaked in the early 1990s, prospects were bleak. The 1993 International AIDS Conference in Berlin announced a growing global spread of the disease with no predictions of effective treatments in the years, and possibly decades, ahead. In this time of despair, Bordowitz produced the experimental autobiographical film Fast Trip, Long Drop, one of the most poignant and influential works to emerge from the era. “By the early 90s I was really burned out,” explains Bordowitz, “I really thought it would be my last film.” Mixing footage of protests, archival material, and reenacted scenes, the innovative 54-minute film draws on the artist’s shifting sense of identity as a young, Jewish gay man living with HIV, while addressing the political climate surrounding the crisis and the stigmatizing, divisive narrative dominating mainstream media at the time. “I’m reporting from the non-infected,” affirms the fictitious newsreader in the film’s opening scene. “And we know who we are.”

With the arrival of effective antiretroviral drugs in the years following the release of Fast Trip, Long Drop Bordowitz’s health improved, allowing him to return to his art practice and to teaching. “I wanted to make work about HIV, but I wanted to also go back to some earlier concerns,” says the 52-year-old artist, who is now a professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. In 1995, he made a film based on Vladimir Mayakovsky’s poem “A Cloud in Trousers,” exploring the struggle between the Russian poet’s romanticism and commitment to the revolution. Meanwhile, the 2001 film Habit is an autobiographical sequel to Fast Trip, Long Drop, partly set in South Africa and addressing equity and HIV drug distribution. In recent years, Bordowitz has pursued more performance-based work, collaborating in 2010 with artist Paul Chan on an Opera adaptation of Michel Foucault’s History of Sexuality staged in Vienna, and followed by a lecture-performance at Tate Modern with British queer performer David Hoyle.

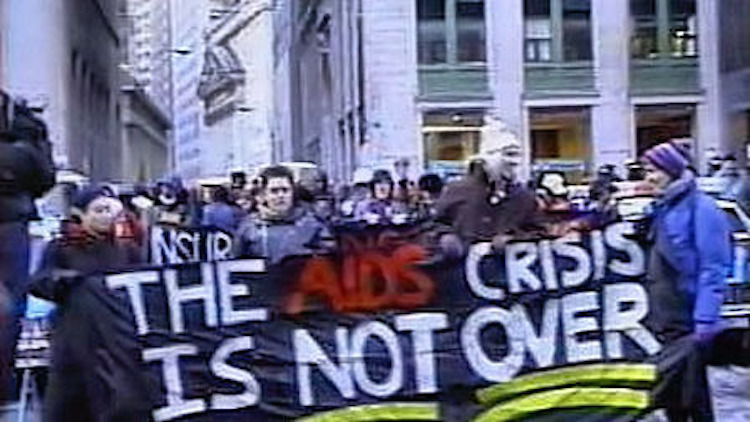

“The AIDS crisis is not over for me. I’m still a person with HIV, I’m taking medication that keeps me alive, that has side effects,” explains Bordowitz. “And I’m also aware that it’s a privilege to have access to the medical care and the drugs that I have access to. The majority of people with AIDS around the world don’t have that kind of access. That’s how I understand that the crisis continues.”

While President Trump has yet to confirm any policy plans to address HIV/AIDS (the web page for the Office of National AIDS Policy has been removed, raising speculations that the program had been eliminated), his intention to roll back the Affordable Care Act, and the public health record of his vice president, Mike Pence, aren’t hopeful. “If Trump is willing to throw 20 million people off of healthcare without replacing it, that will have an enormous impact on people who have different conditions, not just HIV,” says Bordowitz. “All I can say is that I am, along with many people I know, organizing discussion groups, activist groups, and it’s not only people of my generation but many younger people. I’m thinking about how I can lend my energy and voice to the growing resistance to the Trump regime.”

Throughout his lecture-performance series “Testing Some Beliefs,” Bordowitz expresses his belief that art can change the world. When I ask if he still holds that belief in 2017, he looks pensive. “Yes, against all evidence to the contrary. It is a claim that is constantly changing, because the terms themselves are constantly changing — what constitutes art and what constitutes the world,” he responds.

“I think art renders options and pictures possibilities. It has the possibility of forming audiences of people who previously did not imagine that they shared common causes. It is a powerful tool for organizing,” he continues. “That’s how it can change the world.”

Credits

Text Benoit Loiseau